1980s Turbo Bikes Shootout

Boosted and over the top.

Ah, the ’80s. The decade of Back To The Future, Night Rider, Michael Jackson, Culture Club, Madonna, big hair, vivid colors and digital watches. As a motorcyclist and fan of 1980s motorcycles, I’m most interested in the years ’82-’84. Why? Because it was the turbocharged era!

In a very short span the Japanese went nuts over forced induction and produced some wild and memorable machines that came and went as fast as you can say “fuel pressure regulator.” It was only a few years before the manufacturers out-gunned themselves with naturally aspirated, less-expensive models that were lighter and faster (plus better looking) than the turbo bikes they’d created.

Despite all of this there is no denying the coolness of a factory turbocharged motorcycle with, of course, the words TURBOCHARGED prominently inscribed on the bodywork in a gloriously digital font.

Beneath their (at the time) futuristic exteriors, however, resided some fairly basic engine architecture. Honda’s CX500/650 Turbos utilized liquid-cooled, 4-valve pushrod Twins, while Kawasaki’s GPz750 Turbo and Yamaha’s XJ650 Turbo made do with air-cooled two-valve inline-Fours. The XJ even remained carbureted, which, although basic, proved to be the most reliable of the Japanese turbos.

This particular assembly of turbos are in Australia but originally hailed from America, so all feature U.S.-spec lights and exhausts. In fact, everything on the bikes is stock right down to the OEM rubber, grips and levers, and most only have a few thousand miles on them. I really felt like I had stepped back in time. It was a dream come true for me, as I was a wide-eyed kid when these machines were turning heads and I remember how bad I wanted to ride one back then. Riding a turbo bike was equal in credibility to flying a fighter jet as far as I was concerned.

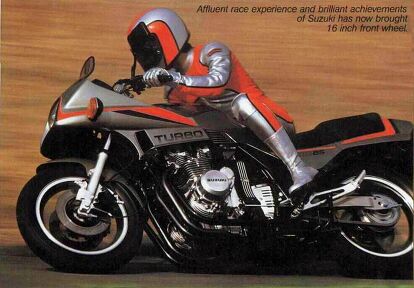

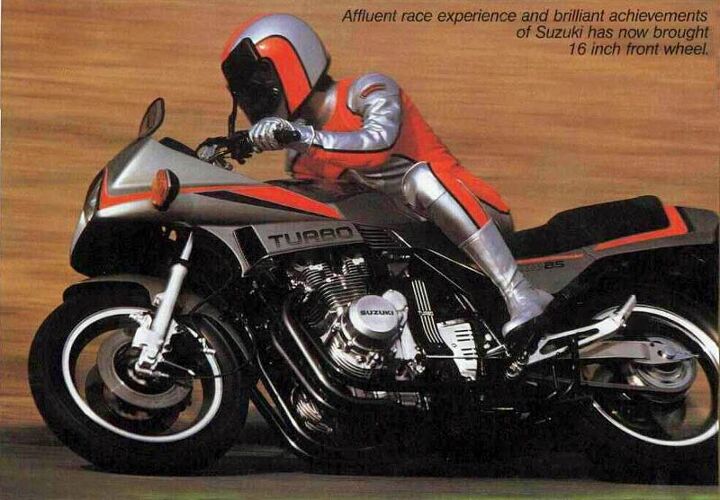

The machine missing from my test is the Suzuki XN85. An epic failure, the Katana-styled bike was the most unreliable and poorly selling turbo bike from the Japanese manufacturers. The XN was slower and heavier than its naturally aspirated GSX750S sibling, plus a lot more expensive. It also would break down all the time and the turbochargers would seize, with a replacement cost almost as much as a new bike! One was on hand for this test, but – you guessed it – the immaculate example with only a few thousand miles on the clock broke down before I got to ride it. The XN85, still failing 22-years on.

For the XN, Suzuki applied the same principals as Yamaha by adopting a ‘blow through’ system, only Suzuki did it much, much worse. They must have been handing out free acid at the factory when Suzuki engineers agreed to mount the XN85 turbo – wait for it – behind the cylinders, on top of the gearbox/upper crankcase. Located here it got zero airflow aside from super heated air from the cylinders. The exhaust headers had to wrap around the entire engine, come up behind it between the swingarm pivot point and the crankcases, just to spool the turbo up. From there the now super heated intake air was compressed and fed to a plenum chamber via a giant loop around the left side of the bike. At least the Suzuki had EFI.

2015 Kawasaki Ninja H2 First Ride Review + Video

So the question is, how do these old heavy-breathers perform? Having recently tested the new Kawasaki H2, I had no power expectations, but I was more than keen to feel how the bikes performed compared to naturally aspirated bikes of the same era. Perfect for me there were era bikes in attendance such as the Suzuki GSX-R750F (first-year model in Australia), Kawasaki Z1, Z1R and a 750 Triple, a Honda 750-Four, Yamaha RZ350, and a few Ducatis.

Honda CX500 Turbo

Top Speed: 128 mph

¼ Mile Time: 12.3 seconds at 106 mph

The first turbo bike I rode was the best looking one, the CX500. The 500 was the first mass-produced turbo motorcycle in the world. There had been limited-run turbo bikes in the past but not a mass-produced model. It was also the first motorcycle to feature EFI when it was released in 1982. Although the pushrod V-Twin was an old design and had remained unchanged since 1977, it did have some benefits. It was liquid-cooled, had strong cases and produced good amounts of torque.

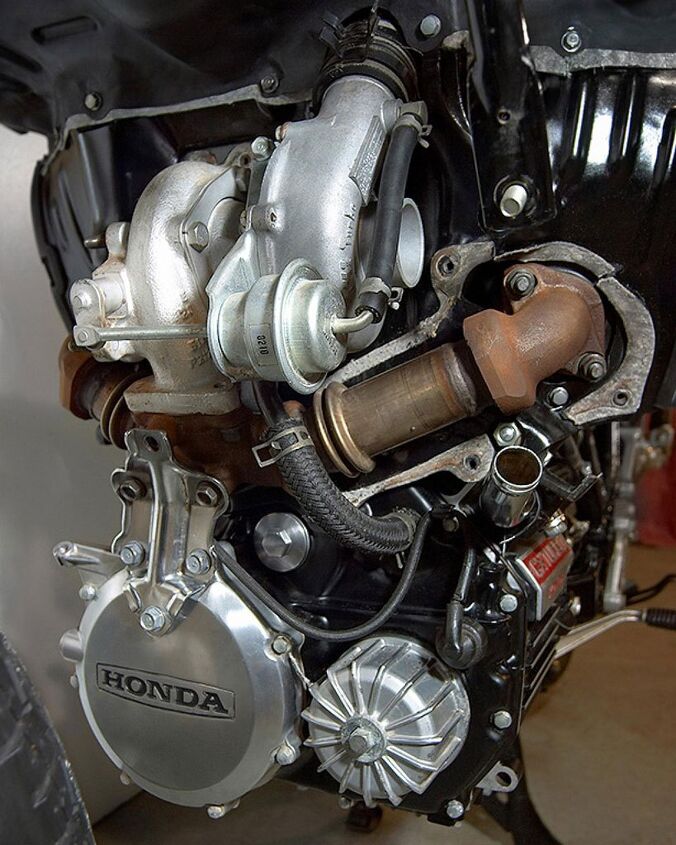

Honda beefed up the internals including the crankshaft, reduced compression and fitted (complex for the day) EFI and a little 51mm turbocharger. The turbo was front-mounted nice and close to the exhaust headers, with a single dump pipe looking very cool on the right-hand side, exiting via a muffler with huge TURBO lettering. The turbo location reduced lag and was a good move.

The CX500 featured TRAC anti-dive front suspension, air-assisted adjustable rear Pro-Link suspension, and twin front rotors with two-piston floating calipers. As a sport-touring bike, it also had a big comfy seat and a tall screen with an upright riding position.

As for the turbocharging system on the CX, it was less perfect than the GPz but much better than the XN or FJ. A basic principle in turbocharging is that intake air temperature needs to be kept as low as possible. This was a pre-intercooling era, so alternatives needed to be found. Honda decided to front mount the turbo between the V of the 80º cylinders, to take advantage of cool air. Of course, what the trade off was is extreme heat generated by the turbo and thus a lot of hot air around the fuel rail and tank. Hot fuel can have as bad an effect on combustion efficiency as hot air does in a turbo system. Front mounting the turbo also reduces lag a little on the CX but header length dictates that it is not as effective as the GPz setup.

The CX turbo draws through an oiled foam filter, not ideal and easily swallowed once deterioration sets in. From there, there is a long intake pipe to the turbo and on the compressed side another long turbopipe leading to the plenumn chamber which is a plastic sealed airbox in this case. The compressed air then needs to pass through yet another set of plumbing to the intake manifold and even through a set of reeds. No wonder there is lag! The set-up is not ideal but it’s not bad for the era and with the 650 there is much improvement – thanks to the extra capacity and compression ratio.

I fire up the CX and it doesn’t miss a beat, idling away with a slight left and right chug as the big crank spins clockwise with the low compression pistons swinging off the ends.

I hop on and familiarize myself with the 500. It is really comfy with a wide, soft seat with a tall screen and high bars, the kind of bike you could ride all day long. It also has that Honda quality paint and graphics, with some nice touches around the dash area.

Honda CX500 Turbo Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Engine | Turbocharged 498cc liquid-cooled 80º east-west pushrod four-stroke V-Twin with four-valves per cylinder |

| Engine Performance | 82 hp @ 8000 rpm 59 lb.-ft. @ 5000 rpm |

| Compression Ratio | 7.2:1 |

| Bore x Stroke | 78mm x 53mm |

| Diveline | Five-speed transmission, wet multi-plate clutch, shaft final drive |

| Fueling | EFI |

| Chassis | Tubular steel frame |

| Front Suspension | Showa conventional forks with TRAC anti-dive |

| Rear Suspension | Honda Pro-Link rear with Showa air pressurized shock |

| Front Brakes | Dual rotors with twin piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | single rear rotor |

| Front Tire | 100/90-18 |

| Rear Tire | 120/90-17 |

| Fuel Capacity | 5.3 gal. |

| Curb Weight | 580 lbs |

Clutch in, select first (no clunk) and off I go. I ease around for the first lap due to the age of the tires (this one has reasonably new Bridgestones as opposed to some bikes in the test that have original rubber). Once I get a feel for the brakes and tires I actually start to push and am surprised. This thing really goes pretty hard!

The CX500 Turbo is peakier than I anticipated, and once the turbo spools up (there is some lag) the power hits quite hard for a short period of time before tailing off painfully, when the bike gets asthmatic. Keep it spinning in boost, however, via the smooth and wide ratio five-speed gearbox, and you are rewarded with a torquey, punchy bike that offers the pull of a much larger capacity motorcycle.

The old-school power delivery is fun – nothing … then boom – a quick rush that sees the skinny forks extend to full length, and it really does make me grin as I lap on the old beast.

The handling is the big surprise. For a bike that looks like a Moto Guzzi on acid, I can’t believe how well it steers and tracks through a turn. Front-end confidence is high and I’m shocked. The brakes are also fantastic – another surprise. At the end of my 30-minute test I’m absolutely blown away.

Returning to the pits I wander down to the next bike and fire it up.

Honda CX650 Turbo

Top Speed: 140.4 mph

¼ Mile Time: 11.9 seconds at 112 mph

The CX650 Turbo is a bored and stroked version of the CX500 Turbo with more compression (7.8:1 versus the 500’s 7.2:1), a fatter front tire, stiffer rear shock and a peak boost of 19 psi from the 51mm turbo. The chassis and bodywork are basically unchanged from the 500 aside from paint and graphics, but the example we have here is much more modern looking than the 500 in my opinion, thanks to the white and blue color scheme.

I roll out of pit lane and onto the main straight, open the big 650 up and I’m instantly grinning! The lag of the 500 is gone and the 650 reacts to throttle inputs much faster thanks to the increase in compression and EFI improvements. There is a strong, grin-inducing surge of power, and with 100 hp at the crankshaft, this bike really is a quick thing. In fact, the front wheel comes up in first gear with a bit of a nudge. The gearbox ratios were revised on the 650 and the entire package works impressively well.

The biggest surprise for me is the smoothness of the fueling. Modern bikes are less progressive on the throttle. Like the 500, the 650 handles really well (again, on modernish rubber), and the brakes are impressive.

The CX650 is a blast. It is fast and it handles well – plus so comfortable you could tour the States on it. What an underrated bike that just slipped through the radar. A real jewel of a motorcycle.

Honda CX650 Turbo Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Engine | Turbocharged 675cc liquid-cooled 80º east-west pushrod four-stroke V-Twin with four-valves per cylinder |

| Engine Performance | 100 hp @ 8000 rpm 70 lb.-ft. @ 5000 rpm |

| Compression Ratio | 7.8:1 |

| Bore x Stroke | 82.5mm x 63mm |

| Diveline | Five-speed transmission, wet multi-plate clutch, shaft final drive |

| Fueling | EFI |

| Chassis | Tubular steel frame |

| Front Suspension | Showa conventional forks with TRAC anti-dive |

| Rear Suspension | Honda Pro-Link rear with Showa air pressurized shock |

| Front Brakes | Dual rotors with twin piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | single rear rotor |

| Front Tire | 100/90-18 |

| Rear Tire | 120/90-17 |

| Fuel Capacity | 5.3 gal. |

| Curb Weight | 573 lbs |

This is a machine that has been well tested and developed. Specifically for the North American market (the only place it went on sale), the CX650 Turbo was created to help avoid the over 700cc tariff on Japanese imports that was successfully imposed after lobbying from Harley-Davidson.

Up next was the ugly duckling, Yamaha’s XJ650 Turbo.

Yamaha XJ650 Turbo

Top Speed: 125 mph

¼ Mile Time: 12.7 seconds at 106 mph

Where the Hondas are high-tech and highly equipped, the XJ is basic. Yamaha attempted to keep the astronomical price tag of a turbo motorcycle down. However, the result is a bike made from leftovers. A Seca chassis, oil and air cooling, pressurised CV carburetors (that actually proved more reliable than EFI) and lastly, a turbo with light-switch power delivery that caused the already bad chassis to get worse!

The Yamaha styling is also, err, well you can decide for yourself…

The XJ has a rear-mounted turbocharger. Why? You have to wonder. I really don’t get it! The tiny turbo was mounted basically where you would find your rear shock linkage on a modern bike. Behind the engine sump, around three inches in front of the back tire. It was like an automatic full-time tire warmer!

This spot was a fail and a half. The turbocharger got little to no cool air. In fact, it got hot air from the already overly hot engine. It was also an eternity before exhaust gasses reached the impeller to spool up the turbo as it was at the end of the collector pipe! So imagine, you open the throttle anticipating acceleration and have to wait all of that time before the turbo comes into effect.

The turbo-piping from the compressed side was routed up behind the crankcases to the plenum chamber and then mixed and distributed by four Mikuni CV carburetors, which had pressurised float bowls to prevent the forced air from basically blowing all of the fuel out of them.

On the intake side of the turbo was another restriction – a large airbox. It was a lose-lose situation. Oddly, one side of the exhaust system on the XJ is fake and simply vents from the wastegate. It is actually a four-into-one not a four-into-two.

I hop on the Yamaha and, unlike the Honda CX500 and 650, the Yamaha does not feel well developed. The seat is thin, the pegs low, the handlebars awkward, leaving me with a confused feeling about the bike. I start up the inline-Four and it idles louder and more smoothly than the others despite one fake muffler.

Yamaha XJ650 Turbo Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Engine | Turbocharged 653cc air-cooled inline four-cylinder DOHC two-valve four-stroke |

| Engine Performance | 90 hp @ 9000 rpm 60.3 lb.-ft. @ 7000 rpm |

| Compression Ratio | 8.2:1 |

| Bore x Stroke | 63.0 x 52.4mm |

| Diveline | Five-speed transmission, wet multi-plate clutch, shaft final drive |

| Fueling | 4 x 30mm pressurized Mikuni CV carburetors |

| Chassis | Steel spine frame |

| Front Suspension | Air preload adjustable 36mm Showa conventional forks |

| Rear Suspension | Dual Showa shocks with air preload and rebound adjustability |

| Front Brakes | Dual 266mm rotors with single-piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | Single 200mm drum brake |

| Front Tire | 3.25 x 19in |

| Rear Tire | 120/90-18 |

| Fuel Capacity | 5.2 gal. |

| Curb Weight | 567 lbs |

I head off for my half-hour of fun, and within a few corners I already know the bike is a fail. It handles like junk; the brakes are weak and the ride position awkward. However, before you think I hate the XJ, let me tell you, there is something stupidly fun about a poorly designed turbo system that is all lag then suddenly all power.

The XJ is a hoot hanging on and letting the poor old Seca chassis twist and weave around. In fact, the XJ650 Turbo is, if anything, one of the most grin-inducing motorcycles from the early 1980s – only for all the wrong reasons.

I went into the test open-mindedly but there is, without doubt, a favorite and it is no secret that the most successful turbo-charged motorcycle to come out of the 1980s turbo boom is the famous GPz750 Turbo, a.k.a. 750 Turbo or ZX750E – depending on what part of the world you’re from.

Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo

Top Speed: 136 mph

¼ Mile Time: 11.2 seconds at 125 mph

The GPz750 Turbo ran the 1/4-mile in an incredible 10.7 seconds with dragstrip ace Jay Gleason behind the bars. That is a fast time in 2015, let alone back then, and after riding the 750 Turbo I truly believe that it is capable of sub 11s. With a whopping 112 hp at 8500 rpm and big torque with 73.1 lb.-ft. at 6500 rpm, the 750 hauls and is great fun to ride.

The standard 750 was a superb sportbike, and the Turbo retains its great handling and sleek looks, which are improved thanks to the Turbo spoiler. The engine got a deeper sump and extra oil scavenge pump, as well as dedicated turbo headers and revised suspension. Geometry was raked out from 26º to 28º to make clearance for the front-mount turbo.

Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Engine | Turbocharged 738cc air-cooled inline four-cylinder DOHC eight-valve four-stroke |

| Engine Performance | 112 hp @ 9000 rpm 60.3 lb.-ft. @ 7000 rpm |

| Compression Ratio | 7.8:1 |

| Bore x Stroke | 66.0 x 54.0 mm |

| Diveline | Five-speed transmission, wet multi-plate clutch, chain final drive |

| Fueling | EFI |

| Chassis | Steel spine frame |

| Front Suspension | Kayaba anti-dive conventional forks |

| Rear Suspension | Uni-Trac rear with alloy swingarm |

| Front Brakes | Dual rotors with single-piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | Single rotor |

| Front Tire | 110/90-18 |

| Rear Tire | 1230/90-18 |

| Fuel Capacity | 4.8 gal. |

| Curb Weight | 531 lbs |

I hop on the 750 and immediately feel the sporting heritage. It is low. It is long (a trend of the era) and sleek, with full fairing, clip-on bars, rear-set footpegs and a long reach to the bars putting me in a tucked in position. The styling, including the paint, sets the 750 Turbo above the others in every sense. This bike means business.

I head out on the 750 and crack up laughing in my helmet by Turn 1 at the end of the long uphill front chute. This thing hammers! It really is quick for a 1983 model motorcycle. After riding almost every naturally aspirated and turbocharged bike from the era, then jumping on this at the end of the day, it is not dissimilar to how I felt riding the new Kawasaki H2 recently. I’m blown away.

The GPz turbo is slightly larger than the CX and XJ units, so despite the shorter header length there is some lag simply due to the ultra low compression ratio of the bike, the slow throttle response of the basic EFI and the diameter of the impellor in the turbo. Once it is spinning, however, there is no stopping the mighty GPz!

The turbo piping was also fantastic on the GPz. Very short – opposite to the others. From the turbo to the plenum chamber was a very short distance around the cylinder block. The wastegate was mounted to the turbo and vented via plumb back to the airbox and the fuel rail was very close to the cylinder-head, with very short inlet manifold. All up it was a system that, for the era, was pretty much perfect. Not much could be done at that time to improve it.

Once the turbo starts to spool up and boost comes on strong, the 750 Turbo takes off like crazy and revs hard all the way to redline – it just keeps on pulling, gear after gear. I even got some wheelspin off some turns. And just when I was buzzing with adrenaline from the mighty acceleration (for the era), the thrills increase as I try to stop the thing!

The 750 Turbo brakes are grossly inadequate, as is its front and rear suspension. The GPz doesn’t handle nearly as well as the CX650, however, it absolutely hammers, so that more than makes up for it.

I think the Kawasaki 750 Turbo will and should go down in history as one of the coolest bikes ever made – and Kawasaki has just done it again with the mighty and manic supercharged H2. Let’s all hope we are about to experience another forced induction era from the Japanese – and that we can enjoy it without insurance or road tax penalties killing them off again…

Until then, may the boost be with you!

Turbochargers

So where did the turbo come from? Well, in terms of the internal combustion engine the turbo has been around a fair while, in fact, it was 1909 when Dr. Alfred J. Buchi of Switzerland first developed the exhaust-driven turbo. It wasn’t until the 1930s when American company General Electric came aboard and started developing turbochargers for military aircraft that things started to progress. Then in 1936 Garrett came into the picture and, as they say, the rest is history.

As far as motorcycles are concerned, the first turbocharged production motorcycle was the 1978 Kawasaki Z1R TC with an additional 15-horsepower and a limited production run of 250.

Before too long, Honda released the CX500 turbo, Yamaha added a turbocharger and interesting bodywork to it’s XJ650, and Suzuki weighed in with the XN85. In 1983, Kawasaki had another crack at the turbo with the Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo. The fad passed within a couple of years.

So how does a turbo work? The turbocharger uses the exhaust gases blown from the engine to spin a turbine attached to one end of a shaft. On the other end of that shaft is the intake turbine, which compresses the incoming air and forces it into the engine’s cylinders under increased pressure, or boost.

Additional fuel is required to keep the air/fuel ratio within a happy range. The more fuel your engine can burn, the more torque and power it will produce.

Early turbochargers were fitted with heavy turbine wheels and the center shaft ran in plain slipper bearings. These two factors caused lag, which is the delay between you opening the throttle and the turbo spinning fast enough to produce noticeable boost.

With advances in design and materials, modern turbochargers with lightweight ceramic turbine wheels and the center shaft running on roller bearings work better on bikes because they spin quicker and easier. This has reduced lag to the point where a turbocharger correctly matched to an engine will provide almost instant boost.

More by Jeff Ware

Comments

Join the conversation

I would love to own a turbo bike. I'm surprised that they are not more popular. i guess the complexity if cost prohibitive. Imagine throwing a http://www.fiercecontroller... on there and cranking up the boost

It is a great shame Jeff was let down by the owner of the XN85 and this clearly stopped him properly researching this amazing bike.

I would like to know where he got the notion of them being unreliable - the number of bikes still on the road across the world, considering the small number made, is testimony to their longevity, which obviously shows they must have been reliable or they would have been scrapped long ago.

He also fails to even mention the innovation that made the bike a test bed for Suzuki's future use of the rear suspension, the smaller front wheel size, and the cooling which became the . Of course it was a heavy bike, and they did severely limit the engine's output - as they underestimated the strength of the modifications they made to the standard engine.

Perhaps he could at least have provided the specifications and to quote the reviews of the time that emphasised the road holding and cornering was regarded in many serious bike journalists at the time to be the best for any production bike.

They are slower than the rest, they are also the only ones that were designed as a turbo bike rather than a bolt on to existing model. They are extremely comfortable, and great for long distance.

They were also very expensive - and Suzuki already had the cheaper much lighter and faster GS750ES only a year from production when the XN85 was introduced.

One day, Jeff, find an XN85 that has been well maintained and enjoy a ride - then produce a proper comparison rather than just reiterating some unfounded views - or alternatively produce some evidence to support them.