2016 Motus MST and MSTR Review

Alabama Slammers

Used to be, there was no such thing as a “sport-tourer.” It’s kind of a silly concept, if you think about it – take the biggest, slowest, worst-handling sort of bike and combine it with the smallest, fastest, best-handling. It’s like crossing an F-18 with the Goodyear Blimp, and nobody will be happy.

Of course, you’re reading this on the Internet, where nobody is happy anyway. Give us power, handling, reliability, locking luggage and price it like it’s on the McDonald’s Value Menu! Give us all the plusses and none of the minuses. Oh, and can you make it in the USA? Cuz ’Murica?

Schizophrenic product requests like this must drive planners and engineers insane, especially when you have to balance so many conflicting demands. Make it happen – all it takes is a huge corporation and hundreds and millions of R&D dollars, after all – and then the resulting machine gets faulted for lack of character. Yeah, the Concours 14 is affordable, fast, good-handling and reliable, say the guys with checkbooks out, ready to buy, but so is the FJR1300 and the ST1300 and the K1600GT … I think I better go think it over and talk to the wife. “Please excuse me,” says the exasperated OEM, “while I insert the pointy end of this JD Powers award all the way into my eye.”

Thank God, then, for the hopeful naiveté of youth. One day, back in 2008, a pair of enthusiasts – an engineer named Brian Case and a business guy named Lee Conn – decided they would build a kick-ass, all-American sport tourer that would be irresistible to self-proclaimed sport-touring customers. You can read the whole Motus story elsewhere on MO – after all, we’ve been covering it from the very start – but here’s the executive summary.

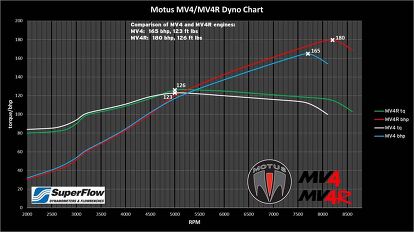

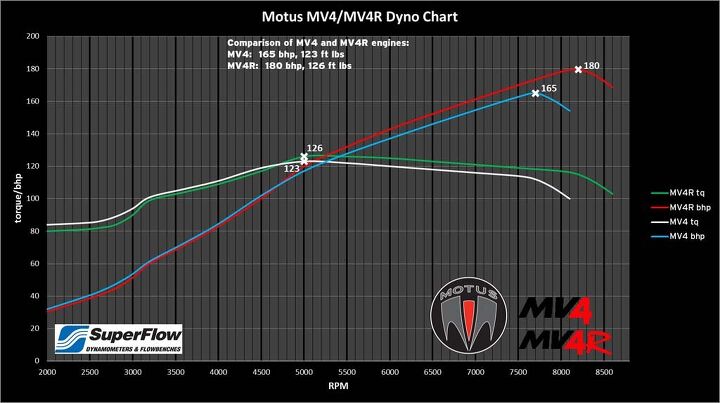

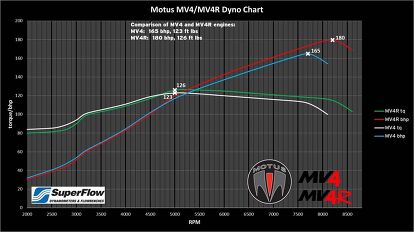

The motor is, architecturally speaking, half a small-block V-8, shrunk down to 1650cc. It was developed by Case and, race-engine specialist, Pratt & Miller, and is impressive. Hydraulic lifters – no valve adjustments required – and pushrods are a nod to tradition, but it’s an aluminum block (engine weight is a claimed 150 pounds without the 75-pound six-speed gearbox) and sports closed-loop EFI, and an 11.5:1 compression ratio. The basic MST makes a claimed 165 horsepower and 123 lb-ft of torque at the crank. The MSTR, with sporty red valve covers, makes 180 hp and 126 lb-ft.

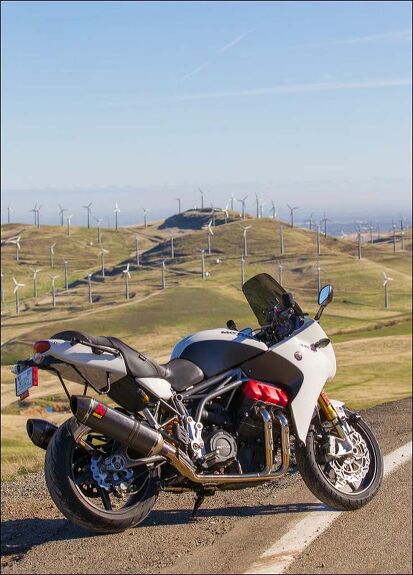

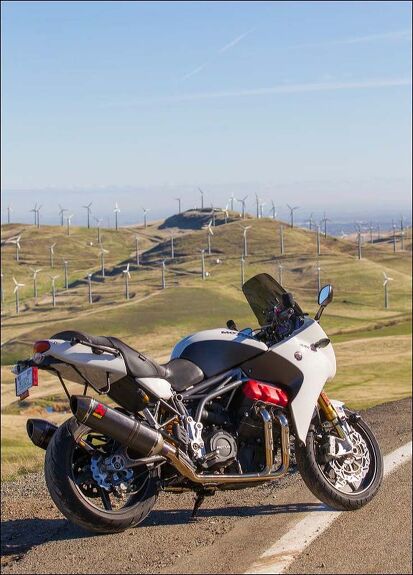

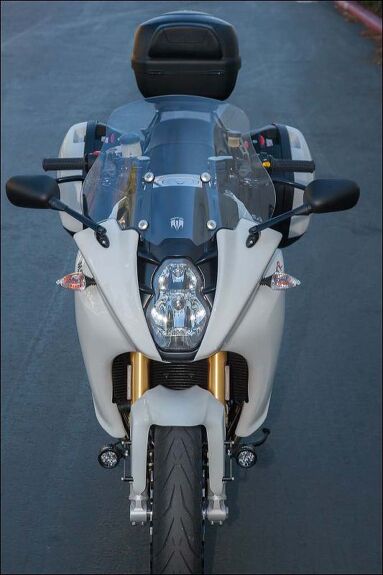

The motor goes into a chromoly tube-steel space frame (also developed by Case and Pratt & Miller, and fabricated in Alabama), with matching swingarm. It puts 58 inches between the wheels, and the Öhlins fork is set for 26 degrees of rake and 4.25 inches of trail. The linkage-equipped rear suspender is by Progressive, and it’s fully adjustable, of course. Wheels are forged aluminum from Italian company OZ, and brakes are by Braking and Brembo. The MSTR gets an Öhlins TTX36 shock, Brembo M4 monoblock calipers, and carbon-fiber bodywork.

The rest of the bike is pretty simple. There’s some simple-looking (but expensive, made-in-South Africa fiberglass) bodywork, a minimal tail, and grab handles that double as mounts for included Givi locking hard cases. The seat is by Sargent’s, and a choice of either a low or high seat are available at no extra cost to the buyer, and the adjustable windscreen is also available in multiple widths and heights. A small but data-packed TFT display delivers the 411. It all weighs in at a claimed 585 pounds with bags and a full 5.5-gallon fuel tank. Expect to see more than 200 miles of range.

I have been reading about this bike since 2010 or so, so I was eager to ride it. After a 2-minute tech brief, I climbed aboard the MSTR. Lee – also a shorty – had the low seats on both bikes which is 32 inches (the high seat is 33.5), though it’s very narrow at the front, making it possible to get both feet flat on the ground despite my 30-inch inseam. The bike is bulky at a standstill and heavy at low speeds, reminding me of a big standard like Kawi’s Z1000. Steering lock was limited as well, but then I remembered I was on a 180-hp sport-tourer and realized it was much easier to handle than it should be.

Riding up into the Altamont Pass for photos took us onto a bumpy, twisty road, and the Motus handled it well. The Öhlins rear was stiff, but I probably could have tuned the harshness out if I had time. The steering felt heavy at first, but after a few miles it felt manageable, and never hard to turn. Feet-up U-Turns between photo passes were easy, especially considering this genre. The bike’s longitudinal crank rocks the bike a little – the transmission’s perpendicular countershaft partly mitigates that effect – but it also keeps the center of gravity very low, tricking the rider into thinking the bike is much lighter. I would not guess this bike is almost 600 pounds. Riding it on slow and medium-speed roads is reminiscent of something like a cross between a supermoto and an ’80s UJM, if you can dig it.

High-speed handling is even better. The Motus feels stable, but the steering is easier as the speeds increase. You can opt for either handlebar when you buy a Motus, but I preferred the HeliBars-built multi-adjustable bar. It puts you in a bolt-upright position that provides good leverage, and you can tune it perfectly for your reach and preferred riding position. The low bar on the MSTR felt like it would be better for shorter, more spirited rides or track days.

The brakes, tires and suspension all work well together. The Pirelli Angels GT’s (with a 190/50 rear) offered plenty of grip and feedback, giving me confidence on gravelly, slightly damp roads. The brakes did what they were supposed to with the lower-spec Brembos, with noticeably more feel, power and bite from the MSTR’s monoblocks. The front Öhlins was predictably plush and controlled (and should be, considering it retails for around $3,000), but I thought the Progressive rear shock on the MST, with its progressively wound spring, was a better match for real-world riding.

I’m saving the best part about the Motus. It’s that motor, and putting half a Chevy V-8 into a motorcycle is as good an idea as it sounds. On paper, the Motus makes about the same torque as BMW’s K1600GT, but it’s where it makes it that’s remarkable. If Motus’ dyno chart is to be believed, it’s making over 100 lb-ft. from 3,000 rpm all the way to the 8,000-ish rpm redline, and over 100 hp at about 4,500 rpm. That means you can be in any gear, pretty much, and just roll on and off the throttle. Wheelies? Well, it’s got a long wheelbase, but the front gets light with a firm twist of the throttle tube, and using the clutch (which is smooth, light and precise) would probably get the front hoop way up there – but that’s not what this bike is for, is it?

It’s for riding public roads fast, very fast, for great distances, and that’s where the Motus excels. The wind protection was nice, nicer than some heavily engineered sport-tourers from other brands, putting my helmet into clean airflow and protecting my body from windblast, even at triple-digit speeds. Engine vibes from the 90-degree engine are present, but it’s a pleasant, organic sort of rhythm, like being on a living being. The Sargent seat is cushy and supportive, with lots of room to move around. But leave it in 5th or 6th, and even though both gears are overdriven, you can roll on and off the throttle to overtake traffic, even on steep upgrades, at any speed, whether you’re going 60 mph or 120, in a blink of an eye. It’s a badass road warrior, with a presence and character completely unique to a motorcycle with such a modern, polished appearance.

So you could tell I like this bike, and I do, but is it the ultimate sport-tourer? Did Conn and Case hit the mark? Well, I can tell you if I could pick any ST to ride coast-to-coast, this would be it – I like my motorcycles small, light and torquey, and having good wind protection and a comfy riding position is icing on the cake. It’s the best-handling and fastest ST I’ve ever experienced, by a wide margin, and the comfort is certainly good enough for 500-mile days. A 720-watt alternator will power all your farkles, and there’s cruise control along with three Powerlet (or BMW) 12v outlets. A heated seat and grips are options. Sure, it has a chain, which some consider a non-starter for a ST, but don’t worry, mile-eaters: it’s warrantied for 20,000 miles, and the steel rear sprocket has a lifetime warranty, even if you never bother cleaning or lubing your chain, like me. But it does have a centerstand, gratis.

It does have flaws and drawbacks. The transmission is pretty rough, hard to find neutral, and clunky and agricultural to shift, even on the test units I rode, which are over a year old and have almost 20,000 miles on the clocks. Speaking of clocks, the TFT displays have a lot of info – including a full diagnostic readout, no OBD reader required – but it’s small, hard to read, placed at an odd angle and is hard to safely work while riding, as it lacks handlebar controls. That last item sounds like a nit, but in the seven years since this bike has been in development, that’s become a standard feature on electronics-equipped motorcycles. And speaking of electronics, there’s no ABS, no TC, no selectable mapping modes. You have to use your mad skillz to keep from crashing, and Lee is unapologetic about that.

But the two big obstacles to most buyers will be reliability concerns and price. Many enthusiasts like the idea of a big V-4 sport-tourer, but are worried about investing in a product from a new company, a company with a challenging task ahead of it. Motus has been around for a while, sure, but the engine maker, Pratt & Miller, is a pretty big company with a long history and a diverse product line, including defense contracting and aerospace. The rest of the parts come from outside suppliers you’ve heard of: Brembo, Öhlins , BST, Akrapovic and others. And the motor is designed to be low maintenance, with hydraulic lifters and a spin-on oil filter. Motus will honor warranty work from “any reputable shop,” according to Conn, and the bikes require no special tools, which would make a BMW dealers’ head explode.

Okay, here’s the elephant in the room – the Motus’ elephant-sized price tag. It’s $30,975 for the MST and $6,000 more for the MST-R (a deal considering what you get for that six grand – 20 extra hp, carbon-fiber bodywork, Öhlins rear shock, premium brakes and BST carbon wheels). That’s a lot of money, but Motus’ Lee Conn likes to point out that top-of-the line Gold Wings and BMW K1600GTs are about the same amount of money, and the average Harley-Davidson Big Twin buyer spends the same after he or she gets all the performance and accessory shopping done. “The price isn’t really that high,” Conn said. “Gold Wing buyers and our buyers are just regular guys.” Think of how many suburban driveways are filled with boats, RVs and Corvettes – the kind of lifestyle tools that can cost far more than the handbuilt, low-volume Motus.

I think the ire from the Internet peanut gallery is because the Motus is just the kind of bike most of these guys want, and they resent having to pay an extra $10,000 or $15,000 to get it. “They want that bike but they can’t afford it,” photographer Bob Stokstad told me in the car on the way home, and I agree. Conn has made it clear he doesn’t want Motus to be a giant company selling zillions of units, but is structured to be profitable selling small numbers (maybe around 300-500) of heirloom-quality motorcycles to serious enthusiasts, the motorcycle world’s equivalent of guys who collect hand-built guitars or vintage record players.

So, if you want a bike that’s built to last, offers superbike performance with the reliability of a Ford Crown Vic and is comfortable, dripping with moto-jewelry and is unlike anything else on two wheels, check out a Motus MST. If you want a performance bargain, consider a used SV650. Conn is unapologetic about the price – it’s hand built, has high-quality components and Motus is a small company that can’t achieve economies of scale like Honda or BMW. “The beautiful thing about motorcycles these days is that there are all kinds of choices,” says Conn, “so if you don’t see the value of the MST, there are options for you.”

Will Motus succeed? Well, 2016 is the company’s third year of delivering bikes to actual customers, and the 15-employee operation is working hard to meet existing orders, screwing together about six bikes a week in the Birmingham, Alabama factory. After more than seven years, Motus has turned a napkin sketch into a running reality, and a pretty good one at that. Best value? Highest tech? Probably not. But as we said in the car trade, there’s an ass for every seat, and Motus is now a real choice for the hardcore sport-touring rider.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

Hoping they are still around and doing well when I feel it's time to move on from my '14 ZX10R. The older I get the more I desire a more long ride friendly bike... that being said I'll probably still be riding my 10R for another 10-15 years.

RIP Motus.