Head Shake - The Art of the Standard

I am a product of the 1970s, the decade of the UJM (Universal Japanese Motorcycle), what’s become known as the “standard” motorcycle. I come from a generation that gazed at Bol d’Or or Suzuka specials on magazine covers and drooled. I was a “standard” guy by any measure, and my meager means at the time made it so. Much as I once drooled over a new Ducati 900SS sitting in a shop next to an equally alluring Darmah, I could no more afford those bikes at the time, much less the upkeep, than I could an Ivy League education. The beauty of those bikes though was evident right down to the attention to detail and artistry of the controls and rear-sets. But I was a rubber footpegs kind of guy; I was woefully standard.

By the time 1982 rolled around, I had actually saved a little money and was in the market for a new bike. That date is important. Unbeknownst to me and most others, the Age of the “Standard” was drawing to a close and on the way to being replaced by the Age of Specialization. What had once seemed unattainable, only gracing foreign paddocks of 24-hour endurance races, would soon be available in street trim in U.S. showrooms. The ubiquitous UJM would give way to cruisers and sportbikes, and later to even more niche markets involving power-cruisers and Paris-to-Dakar lookalikes. It took a few decades, but you would occasionally hear the passing of the UJM recalled by moto-scribes with a certain amount of lament.

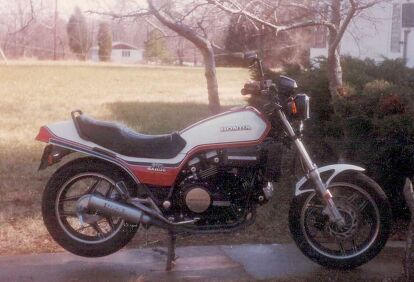

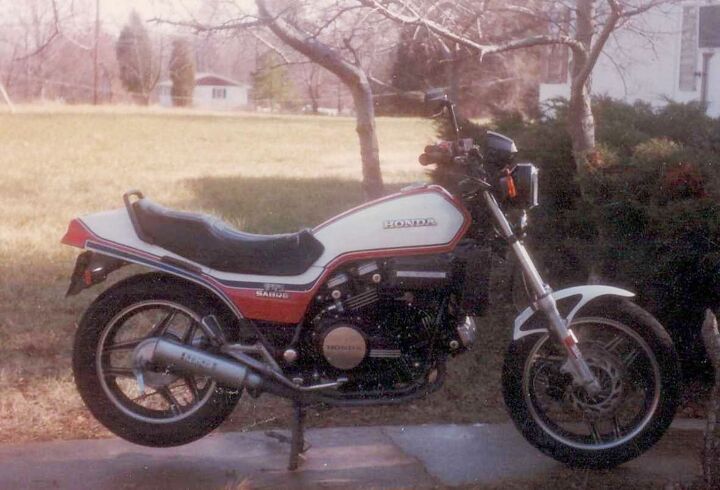

I felt this passing acutely in 1983, a year after I bought a new 1982 Honda Sabre. In 1983 Honda introduced the Interceptor and everything was forever changed. Ninjas, GSX-Rs, VFRs and CBRs, and FZs and FZRs followed. If I had only known, I would have waited a year, and for once something other than “standard” would have been obtainable by my altogether standard income strata credit rating. What was lost on me then is what I would have missed if I had waited, I would have missed all the wonderful qualities of the “standard” motorcycle that only became evident when they were gone.

The simple fact is most of us live and ride in a “standard” world. It took me some years to learn that lesson, I’m a little slow on the uptake at times, and the RC51 sitting in the driveway is testament to that fact. But I recognize now the utility of utility, the value of the all-around motorcycle, one capable of being fun on the backroads yet also capable of lugging through rush-hour traffic or delivering you 750 miles away when the sun sets for the day. And I know the satisfaction that comes with making a ride your own. Standards were blank canvases that lent themselves to their owners’ modifications more so than many of the specialized rides that have come along in the intervening years.

My old Sabre was a case in point. A tip-over in a raucous barn-venue birthday party provided a great excuse to spend money getting it repainted. A tank, sidecovers, and tail section are rather simple to redo compared to acres of bodywork and does a lot more to alter the appearance, and a TZ750 front fender went on in place of the dented chromed OEM Honda piece. The Kerker replaced the stock exhaust that I crunched at speed on a buddy’s GS750 centerstand tang getting a little too rambunctious recreating the Isle of Man TT on the backroads of Kentucky. Little things like an S&W air fork balance kit were added and, before I knew it, I had the dubious claim of having a one of a kind Honda Sabre.

I know what you are thinking: “Well, so what?” I would probably think the same thing except for the fact that it was mine and I really liked it, and that is after all kind of the point of modifications and whatnot. That is why I have been encouraged by what I have seen in recent years with manufacturers introducing more standards or retro models into their lineup. I’ve taken particular notice of Yamaha’s Sport Heritage line.

Related: Duke’s Den: What Is Yamaha’s Sport Heritage Line?

These new bikes are far from the UJMs of old, though, in any pejorative sense. The fit, finish, and attention to detail in their planning and build quality is evidence of that fact, from Honda’s seamless gas tank on their CB1100EX to the Yamaha XSR700s use of removable tail-section mounts and fuel tank panels to further enable those who wish to customize and modify the bike. They are “standard” in the sense they harken back to timeless design qualities and ergonomic layouts that have worked throughout time, but they are beyond ordinary in any 1970s sense.

The degree to which these bikes emphasize retro as inspiration (XSR700) versus retro as spec sheet (CB1100EX) varies, but the theme is consistent: 1) Real world ergonomics, 2) Lends itself to customization, painting, etc., with minimal bodywork 3) Jack of all trades, interstate to backroad. The Yamaha XSR700, and its larger sibling, the XSR900, may most epitomize the modern evolution of the standard in contrast to the retro appeal and aesthetic of the air-cooled Honda CB1100EX. The degree to which you want to travel back in time is your choice.

The old UJM evoked images of mass production and affordability, and it became a pejorative term in a way implying cheap. But it turns out affordable was not cheap to make. All those air-cooling fins, graceful side covers, and valve covers cost money to manufacture if you aspire to an aesthetic standard somewhere north of roto-tiller.

To run sans fairing calls for a rediscovered appreciation for metal and attention to detail in components, and if they happen contribute to performance, all the better. Something that has been lost is that engines were once works of art to appreciate: The 4-into-1 exhaust of the early CB400F was a thing of beauty, the CBX mill was awesome to behold, and these were not things to cover up with plastic.

In the intervening years, engines morphed into efficient, water-cooled, plastic-covered, internal-combustion devices with all the allure of a sump pump. Plastic is cheap, while making attractive engines for the world to see is expensive. Today’s manufacturers struggle with those realities and try to balance aesthetic considerations against price-point priorities. The demands of the 21st century come with their own price; try making a catalytic converter attractive. No, really, please, anyone, try. Whoever figures that out will be the next George Kerker.

So I encourage you, those of you who live in the “standard” world filled with traffic and monthly bills, but also backroads and the occasional interstate adventure. Fall in love with a standard, get some soft bags, and maybe a vision of what you would like to see it become, money permitting, and ride the wheels off the thing. Clip-ons are for race tracks, and the front-leaning rest position is for basic training. “Standards” became standard for a reason: They are built for this world most of us live in, and they are uniquely suited to be modified in a way that is not “standard” at all. The bike, like the world, is what you make of it.

Ride hard, enjoy every mile, look where you want to go.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

What? A "standard?" It's "nek'd!"

I do, sometimes, miss my '81 GS1100EX. But Tuono V4 definitely fills the gap.

My FJ-09 is a great example of an updated standard concept. Not too heavy, comfortable seating position, ABS, handles everything from commuting to touring,