Evans Off Camber - Soul Food

For some reason, people tell me their stories. Throughout my life, I’ve always had the experience of complete strangers just starting to tell me about themselves. Once, while riding across the country with a friend, she said she would not allow me to take my helmet off at any more gas stops because my conversations were delaying our progress. Similarly, I was amazed on my first cross-country bike trip how many older couples in campgrounds invited me into their RVs and cooked me dinners while sharing their motorcycle stories and the role two wheels had played in their youth, how much they missed it, and, most importantly, how grateful they were for that special time.

These weren’t Uncle Bob stories – you know, where they bought a motorcycle and had a life-threatening experience and vowed never to get on “one of those things” ever again – either. These were people whose lives had either naturally grown away from motorcycling or had forced them to make a hard choice that, while they regretted the loss of motorcycling, they valued the results made possible by the sacrifice. Plus, they clearly enjoyed telling of their time on motorcycles, and I like to listen to stories.

But these aren’t the people I’m trying to write about here.

Throughout my two-wheeled travels, I’ve encountered a few people for whom motorcycling is more than merely life-enriching. Rather, for them riding has elevated their lives beyond some very real limitations and allowed them to live their lives with a fullness they had, in some cases, never thought possible. These were people I typically met during chance encounters, like the Gold Wing rider I shared a meal with at an Arizona diner counter. This guy told me that he rode every day despite his arthritic pain because he’d been riding so long that he was certain that, if he stopped riding, he’d literally stop living.

Evans Off Camber – Motorcycling Saved My Life

Then there’s the Harley-riding Vietnam vet who I worked with almost 30 years ago on an ultra-low budget movie – before I’d even become involved with motorcycles or moved to California. As we were carrying an 80-pound lighting ballast down a flight of stairs behind an apartment building, he casually mentioned that he hoped we wouldn’t be working late that night because he didn’t want to miss his wheelchair basketball game. Naturally, since we were both standing, holding a heavy piece of equipment, I had questions. Long story short, he’d lost both his legs below the knee overseas. Wheelchair basketball and motorcycling had made it possible to work his way back to the type of life he initially thought he’d lost when he was wounded.

However, in two instances I don’t have to depend on my inadequate memory and can share people’s own words about the transformative power of motorcycles in helping them to overcome physical challenges – ones that their doctors told them they were foolish to attempt.

The first, poet Tom Andrews, I met on a bike introduction in Italy. I was a budding motojournalist. He was in Italy on an academic sabbatical conducting research in the Vatican libraries and was excited to be attending the introduction as a freelancer. Tom was a couple weeks shy of exactly one year older than me, so we hit it off. At some point during our time together, we discovered that we shared a belief in the spirituality and healing quality of motorcycling. A fascinating conversation ensued.

Tom was also a hemophiliac – who rode motorcycles. Take a moment to wrap your head around that.

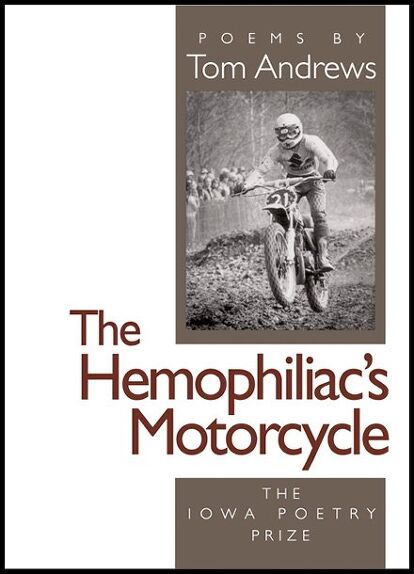

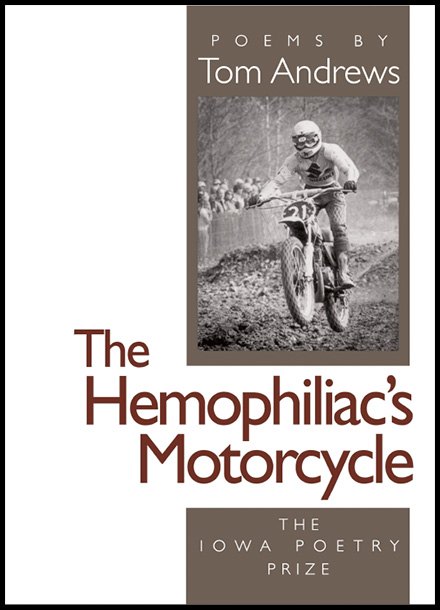

In fact, his case was so severe that a common slip and fall could put him in mortal danger. Yet, as a teenager he’d raced motocross, and as an adult, he continued to ride motorcycles, despite the incredible risk for him. A few weeks after our chance meeting, a package containing Tom’s award winning book of poetry, The Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle, arrived at my house. (You can read it here.) In the title poem, he began with:

May the Lord Jesus Christ bless the hemophiliac's motorcycle, thesmell of knobby tires,Bel-Ray oil mixed with gasoline, new brake and clutch cables andhandlebar gripsthe whole bike smothered in WD40 (to prevent rust, and to makethe bike shine),may He divine that the complex smell that simplified my life wasperforming the work of the spirit,a window into the net of gems, linkages below and behind the givenmaterial world,my little corner of the world's danger and sweet risk, a hemophiliacdicing on motocross tracksin Pennsylvania and Ohio and West Virginia each Sunday from Aprilthrough November,the raceway names to my mind then a perfect sensual music, HiddenHills, Rocky Fork, Mt. Morris, Salt Creek,and the tracks themselves part of that music, the double jumps andoff-camber turns, whoop-de-doos and fifth gear downhills,and me with my jersey proclaiming my awkward faith - "PoweredBy Christ," it said above a silk-screened picture of a rider in aradical cross-up,the bike flying sideways off a jump like a ramp, the rider leaning hiswhole body into a left-hand corner

In another poem, “Codeine Diary” details Tom’s experience in the hospital recovering from a misstep on an icy sidewalk that might have been trivial for most people yet threatened him with paralysis. He points out the disbelief of the doctor treating him when she learns of his love of motorcycling:

When I told my hematologist that as a teenager I had racedmotocross, that in fact in one race in Gallipolis, Ohio, I had gottenthe holeshot and was bumped in the first turn and run over bytwenty-some motorcycles, she said, "No. Not with your factor level.I'm sorry, but you wouldn't withstand the head injuries...

Even reviewers of his poetry on Amazon.com told him to stop riding, to lead a more sedentary lifestyle so that he could go on writing. Sadly, I lost track of Tom in the hustle of everyday life and only learned, after stumbling upon and rereading The Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle last year, that he had died, according to his Wikipedia entry, “as a result of complications from his hemophilia” at a mere 40 years of age. A talented man who, without motorcycling, could not have left us with this image which only rings more truly when we consider the high stakes of the miracle referred to in the text:

on a certain Sunday in 1975-Hidden Hills Raceway, Gallipolis, Ohio,a first moto holeshot and wire-to-wire win, a miraculously benignsideswipe early on in the second motobending the handlebars and front brake lever before the possessedrocketing up through the packto finish third after passing Brian Kloser on his tricked-outSuzuki RM125midair over the grandstand double jump

MO reader, John A. Stockman, shared his motorcycling story in the comments for my very first installment of this column. His post immediately captured my attention by beginning with, “motorcycling saved me from certain mental/physical decline because of my disability.” Stockman went on to outline the repeated surgeries to counteract his disease (SEDT, a genetic defect in which his own body destroyed his cartilage, causing his joints to fuse together), painful physical therapy, and an awe-inspiring level of human effort to achieve his goal of riding motorcycles. He did this mostly without the support of others because medical professionals and friends alike felt that motorcycling was too dangerous. Throughout his travails, however, his grandfather, who represented over 100 years of family history riding motorcycles, offered him the support he needed to pursue his dream: “It was motorcycling that got me out of my personal pity-party, feeling sorry for myself, and gave me a goal to strive for. In spite of the fact that everyone (except my grandpa) put me down, abandoned me and denigrated me for wanting to get my physical freedom back through motorcycling.”

Stockman’s message that motorcycling has been the heart of a well lived life can inspire others, giving them hope. “It was all WORTH IT and I’d do it all over again just to be able to enjoy the physical freedom that I could not have experienced in any other way, except through motorcycling.” he wrote, ”Even though my ambitions to be a pro motocross rider and road racer were not obtainable, the fact that I achieved what I did was just as fulfilling to me as standing on the podium in a world-class racing event.” ( Read the full text of his comments.)

These stories need to be told because they can, perhaps, give others hope to participate in life at a level which they never thought possible. In an era with such profound negativity circulating, hope is an important thing, a seed to be planted and nourished. Hope is needed to surmount obstacles both great and small – both personal and as members of the human race.

Throughout most of my adult life, I’ve battled with depression. This is not something I share often (almost never), though I’m sure that my closest friends probably know intuitively. Battled is a deliberate word choice since not a month goes by in which I don’t find myself at some time with the sensation that all of the oxygen has disappeared from the room, and my thinking has begun to cloud over. Through experience, I know that action needs to be taken or I’ll soon find myself living in a world that seems to be made of jello and everything slows down to a crawl – except for the negative tape loop playing in my head.

Like many people with this illness, I’ve tried alcohol, recreational drugs, sex, food, TV, you name it, to escape the downward spiral, but they only offered me false, temporary numbness. Like the aftereffects of Novocaine in the dentist’s office, the sickness was always there waiting when the feelings started to return. Only two activities (and the care of a couple talented doctors) can short circuit my cycle of despair once it gets entrenched, so I apply them proactively. Both involve physical action. Both also succeed where avoidance tactics fail because they locate me within my body and force me to live in the moment.

When things get tough, I increase my running. Often to daily. Sometimes even multiple times in a day. The glow of muscles after physical labor reaches all the way down into the metaphorical heart. Motorcycling takes care of my soul. At low points, I try to squeeze in as many rides as possible – even if they are only a couple miles long. These activities locate me within the proper space and time.

This past Saturday, as I left the assisted care facility where my mother now lives and thought about the two family members on the other side of the continent engaged in battles with cancer, I felt a familiar ache in the hollow of my being. However, I was grateful that I had ridden to the facility and that I had a 40 minute ride home. Merging onto the freeway, I was grateful for the sun on my back, grateful for the air flowing past my body, grateful for the traffic and “Shine on You Crazy Diamond, Pts. 6-9” whispering in my earphones as I worked my way between the lanes of slowed cars. I smiled as the traffic broke and the XR rocketed back up to 80 mph. Even after hitting an unseen piece of road debris shortly before my exit, causing a massive wobble as the rear tire suddenly deflated, I was glad for the ride. This gratitude continued for the mile and a half that I nursed the Beemer home at 10 mph on a completely flat tire. Another motorcyclist waved and shook his head, and I mimed banging my helmet with my hand in mock frustration.

But I was still grateful. And sad. Sad for the way that age treats some people and how much pain illness – or life, for that matter – can cause people we love and how much we miss them when they are gone. But I’m grateful to be here and aware enough to experience these feelings fully – a large part due to my time on motorcycles and the people I’ve met on them. Because of my gratitude, I have hope, and hope, not happiness, is the opposite of depression. Hope, I believe, is what the world needs at this time in history.

At that moment, I knew what I needed to write for this week’s column.

Motorcycling makes it possible to experience many more things in life than just motorcycling. So, go out and live it.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

I am blessed to be free of disability or other circumstance that could prevent me from riding every day, for which I try to me mindful of and ever grateful. I do have a good friend however who suffers from cerebral palsy and can barely walk, but he rides every chance he gets; he has no disability whatsoever when in the saddle! I get your article, but probably not on the level he will when I forward this to him. Thanks man.

There are very, very few things in my life that distract me enough from my dark thoughts and feelings to keep me going. But riding - and considering myself a serious motorcyclist - is the one thing that actually makes me feel like life is worth living.