Evans Off Camber: Life As Risk

You can't really live in a protective cocoon

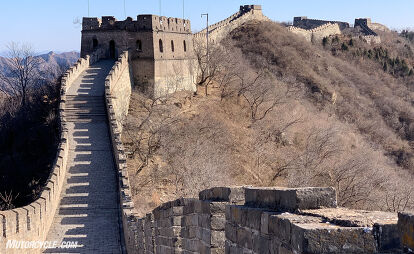

The Tuesday before Thanksgiving, I found myself at the top of the longest staircase I’d ever seen. My family and I were on a six-mile hike along the Great Wall of China, and we’d just traversed miles of the unrestored wall, clambering over stones that had fallen out of place and pushing through the trees that had grown in the centuries since the Wall’s construction. I’d expected the going to get easier once we reached the area that had been restored just 45 years ago, but this length of stairs pulled me up short. We’d encountered similarly steep sections of steps in 20-30 foot chunks along the wall but nothing like this. In the time of the wall’s construction, the terrain it traversed dictated its shape since the high explosives and heavy machinery we take for granted in modern construction weren’t available to lessen the mountain’s angles to suit those of humans on the wall.

Motorcycles and Risk: What Do We Tell Our Mothers?

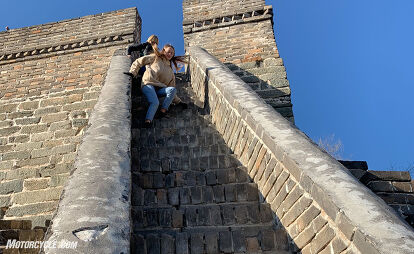

As I stood at the top of a staircase that I’d estimate to be an eighth of a mile or more of impossibly steep, unevenly spaced stairs, I found myself almost consumed with fear. Although I am essentially a cautious man by nature (motorcycle shenanigans aside), I wasn’t afraid for myself. It was for my 10-year-old daughter. Was she capable of maintaining the mental focus necessary to descend these steps without incident? With no handholds or ropes on the staircase to interrupt a fall, a missed step could prove fatal. So, I took a moment to impress upon her the importance of paying attention to every step and began to lead her down, telling myself that if anything happened, I’d throw myself on top of her to stop her from tumbling all the way to the bottom.

Of course, we made it down safely, and my fears were overblown. The initial steep section eventually gave way to more manageable steps. Still, it brought to the center of my attention the role that risk plays in everyone’s life. I’d been thinking for days about risk, so perhaps I was primed for this kind of reaction. You see, my friend and former counselor (and according to the state of California, the person who legally married me to my wife), Richard Carr set off earlier this year to fulfill his lifelong dream of sailing around the world. During his initial extended voyage in the open ocean, sailing from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, to the Marquesas Islands, he was lost at sea. Neither he nor his boat, Celebration, were ever found. His daughter, Ali Carr Troxell, wrote a moving account for Outside Magazine that reconstructs as best as possible what likely happened to her father, and I’d read the article shortly before leaving with my family for China. (You can read it here.) Sometimes dreams have a heavy cost.

Most people spend their lives blissfully ignorant of the risks they’re taking, and when confronted with the consequences of their behaviors, they are frequently surprised. Think of the texting or eating driver cruising down the interstate at 80 mph in traffic. Or how about the health effects of smoking, vaping, or eating nothing but fattening foods? Or living a sedentary life for decades? These are all known risk factors for preventable deaths in the U.S.

Most people probably don’t think of driving cars as being particularly dangerous, but the approximately 37,000 people in the U.S. who die in car accidents annually might say otherwise – if they could. Or what about the roughly 88,000 alcohol-related deaths annually? Yet, the first thing out of peoples’ mouths when you mention driving a car or drinking alcohol isn’t about how dangerous they are. Rather, people brag about how much they can drink. Frequently, when someone I meet finds out that I ride motorcycles for a living, they comment that they could never ride a bike because it’s so dangerous, yet only about 4,000 people die from motorcycle accidents annually in the U.S. (Yes, I know this is influenced by the much lower number of people who ride motorcycles.)

While I’m not about to claim that riding motorcycles isn’t more dangerous than driving a car, I do think that people’s perception of risk is greatly influenced by their familiarity with the activity. Consider my experience on the Great Wall. Despite the innumerable times I’ve descended stairs, those hand-made brick steps were different in their length, steepness, height, and depth. I’d, quite literally, never encountered steps of this kind before in my life, and I reacted to this unfamiliarity by projecting my fears of the unknown onto my daughter. As a competitive gymnast, she’s certainly more fit and has better balance than me, and she certainly has the skills to descend that staircase without assistance.

Evans Off Camber – Precious Cargo: Riding With Kids

Since parenthood has been aptly described by author Elizabeth Stone as “forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body,” I don’t think we’ll ever be able to prevent a parent’s initial protective reaction towards their offspring and a perceived risk. At the same time, knowing that a sedentary lifestyle is the second most common cause of preventable death in the U.S. should make us acknowledge that hiding our children away in the “protective” cocoon of the couch might actually shorten their lives. We need to accept the fact that leading a full life demands accepting some level of risk. The choice each of us has is how and where we decide to embrace it.

My experience is that people who have chosen to undertake inherently dangerous activities on more than a cursory level generally go into it with their eyes open. They acknowledge the risk, but they don’t dwell on it. They use this acknowledgment as a means of addressing and minimizing their exposure where possible. I know that this has affected my motorcycling. I started with a motorcycle safety course. I’ve always worn the best safety gear I could afford. I’ve continued my motorcycle education by reading books, taking riding schools, and talking with riders who are significantly more talented than I am.

However, before people get to the point where they choose to ride motorcycles, we need to make them consider it as an option. Perhaps what motorcycling needs to grow the sport – or at least maintain its current level – is for us to normalize it. Make motorcycling less of an unknown and thereby decrease its perceived risk. At the recent International Motorcycle Show in Long Beach, CA, I had the opportunity to observe one method of demystifying motorcycling. A display called Discover the Ride was allowing non-riders to take a moment to ride an electric bicycle before moving to a detuned Zero motorcycle in a small closed course. The approach effectively took the familiar (a bicycle) and transferred the feeling to something new (a motorcycle). Still, as good an approach as this is, it can only have a limited reach.

It is incumbent upon those of us who wish to grow the sport we love to spread the word, to make motorcycling more familiar, more a part of non-riders’ everyday life. We can do this by riding responsibly and wearing proper gear. Mentor new riders or people who express an interest in motorcycles. Ride your bike to work or to parent-teacher night or to vote. Be visible. Place your helmet on the table next to you at a coffee house. Answer questions about riding in a self-effacing way. If the topic of fear comes up, be open and discuss your approach to managing risk. People will appreciate your honesty more than any bravado.

Most importantly, go ride. Live your life. It’s the only one you’ve got. Don’t be one of the people who lets life pass them by, bathed in the blue glow of the television.

When I think of my daughter’s climb down those stairs on the Great Wall, I experience a feeling similar to the one that comes over me as she repeatedly tumbles head-over-heels, during the gymnastics floor competition. A mixture of hope, fear, and admiration washes over me as I know she’s living her best life, doing things I could never be capable of doing. Yes, there are very real dangers, but we’ve done what we can to minimize them. The rest is in the living as we pursue our dreams.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

https://uploads.disquscdn.c...

As the great Mike Cooley of the Drive-By Truckers put it: " Living in fear is just another way of dying before your time"