Archive: 2000 Yamaha R7-1 Hybrid

Old soldiers might just fade away, but what happens to old race bikes? Basically the same thing. Though a few GP bikes still get destroyed to keep engineering secrets secret, most old race bikes, or many of them anyway, get bought up by guys with more money than they really need, to park in the den. Others get bought up by type-A riders who want the ultimate trackday weapon (but the joke is shortly on them, since the life expectancy of any competitive advantage is, well, it’s short). And some get bought up by collectors, possibly with the hope that today’s deeply discounted last-year’s greatest thing might someday be the next Crocker or Brough Superior or even gray-market RZV500R.

This Yamaha R7-1 we bumped into on a workbench at MotoGP Werks is a little of each. A big attraction of having an old racer around may be to transport yourself back to that one particular summer or two; the Pepsi sticker on an old RGV Suzuki, the Fast by Ferracci logo on a 916, the scarfed camel on a Smokin’ Joe’s Honda… they all take me straight back to when it was pretty dang exciting to be an American roadracing fan. I mean, not that it’s not exciting still, but… maybe I was more exciting then. Or more excitable? Seeing this old bike on the lift, with the tell-tale scar where its frame was sawed in two to accommodate an R1 engine, took me right back to the glory days of the AMA’s old Formula Xtreme series. The idea was anything goes – as long as it was based on a bike that was street-legal in the US, or something like that. Therein lay the rub. If the rules were clear at the time, I’m not certain. They’re nowhere to be found anymore.

Our friend Larry Lawrence takes up the plot in a Cycle News archive from last year: “The X Games launched in 1995 and from that point onwards in the ’90s if it wasn’t extreme it wasn’t happening. If the ’70s everything was ‘Super’, the ’90s were certainly extreme. Oh, and make that Xtreme – the X had to come first to show you just how Xtra Xtreme it was. AMA Pro Racing rolled with the tide and in 1997 launched Formula Xtreme, replacing the old AMA SuperTeams Series. While the name may have been faddish, the competition in the series was top-notch.”

By 2000, Chuck Graves had interpreted the rules to mean that a Yamaha R7, an exotic homologation 750 never sold in the US as a streetbike, could be bent into FX racebike form by shoehorning a 998 cc R1 engine into it. The AMA had already told one team the R7 wouldn’t be legal for the class, but, hey, it was Xtreme, and we had mullets. In 2000, Chuck himself finished 6th on the R7-1 in the AMA FX race at his home track, Willow Springs, and by 2001 things had gotten serious: Chuck decided to step up by bringing Damon Buckmaster and Aaron Gobert onboard to ride a pair of the hybrids. In that first season, Buckmaster lost the FX championship to John Hopkins and his Suzuki by one point; Hopkins took his big trophy and departed immediately for the Red Bull Yamaha 500 GP team. AMA FX was kind of a big deal.

In 2002, Buckmaster exploded out of the blocks on his R7-1, winning the first three AMA FX pole positions and races. Suddenly the rules mattered. Roadracingworld.com has most of the drama archived. From an April 16, 2002 post on RRW: “AMA Pro Racing declared the R7 illegal in 2000, yet refused to accept protests of the R7 in 2001… In the July 2000 edition of Roadracing World, then AMA Pro Racing Communications Manager Bill Nordquist was quoted as saying, after Attack Racing was not allowed to run a YZF-R7 in Formula Xtreme at the May 2000 Sears Point AMA National, ‘The R7/R1 situation came up, along with other topics, but at no time did Rob (King) say it was a legal combination. The R7 is produced as a racebike, and is not supplied as a streetbike to customers.’

By April 13, 2002, again quoting Roadracing World, the official AMA position had evolved here on the R7-1’s eligibility: “The rule book wording is unclear on the subject of ‘street use’ and therefore does not specifically exclude this motorcycle. The Yamaha R7 and the Yamaha R1 are listed on the AMA Pro Racing list of eligible motorcycles for Formula Xtreme. The original intent of the approval rules in FX is not distinctly reflected in the current wording of the rule book resulting in a ‘loophole’. The street use requirement can be read as not necessarily for US street use. The R7 is streetable in most other countries since the machine is homologated by the FIM for World Superbike competition.”

Five weeks later, and we’ve reversed course again: “… Other evidence included an MSO for a YZF-R7 sold in the U.S., which was clearly marked that the bike was not legal for street use. The Board rejected AMA Pro Racing’s contention that the rule requiring machines to be sold for street use in the United States was unclear, and the contention that a bike being legal for street use anywhere in the world made it legal for AMA Formula Xtreme. The Board blamed Pro Racing for not better communicating with teams, and it was because Graves Motorsports Yamaha was not clearly warned that its R7 would not be allowed in 2002 that the Board allowed Buckmaster to keep his finishes and points earned to date despite finding the bike clearly illegal.”

What’s a girl to do? Dunno, but we do know what Graves Motorsports did, because our friends at Iconic Motorcycles have Mr. Buckmaster’s bike on consignment, along with a description of it by Damon himself. (Careful, he really begins to warm to his subject by the end.)

“After the protest the AMA decided that the R7/1 was in fact not in the spirit of the rules and decided to allow the team to keep the previous rounds’ six wins, but not allow the R7/1 creation to race the rest of the season in its current guise. So Graves and Company ripped back to the shop and went about making the R7/1 “conform” to the rule book.

“I have many factory race bikes that are essentially one off frames, motors, etc that all ‘conformed’ to the rules of the time. Those just kinda bent a steering neck here or there, used ‘unobtanium’ parts, but generally looked like the production model. What Graves and his boys came back to the grid with next week was nothing short of masterful manipulation of rules and engineering. They basically covered the existing R7 frame with about 40% of the frame rails of a production R1. This allowed the tank to be changed to a stock R1, and then they added an R1 tail section. The skillful addition allowed the Team to continue crushing the competition with Buckmaster at the next 8 rounds on his way to the FX Championship. On top of that the frame modification made the bike even better due to the extreme bracing.

“The reason why this bike was winning everything in sight is because it handled better than anything else on the grid by a far margin. The front end on the R7/1 is as close to perfection as you can get. The rear speaks to the rider’s throttle input like no other bike I have EVER ridden. I can back this thing into a corner full on the front brakes so smoothly it’s almost telepathic. The front fork is a rare FACTORY Öhlins 46mm USD with magnesium lowers. These jewels are clamped in place by a massive Graves adjustable billet triple tree. The front brakes are the GP-spec Brembo Endurance series with titanium pucks. They are connected to the Brembo radial master cylinder via quick disconnect aircraft style dry break stainless steel lines. The rear is suspended by a factory Öhlins one-off shock that was originally designed for Formula-1 Ferrari.

“I just had it refreshed and the technicians at Öhlins are asking me how I got my hands on it, as they have never seen one released from their facility. Anyway they refreshed it and grudgingly sent it back to me. The frame is really just an R7 factory unit with extreme bracing over the top third of it from the headstock to the mid spar. The rest is all YEC FACTORY kit stuff. Swingers, quick change spindles, etc. All from the Suzuka 8 Hours YEC R7.

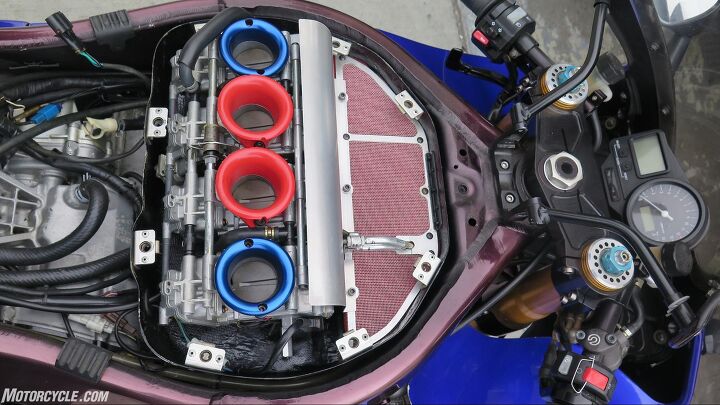

“When we finally get to the motor things really get interesting. The Graves Boys built a true mental giant. Yes, the R1 based 1078cc, 41mm Keihin fed, carbon ram-airbox making honking horsepower – over 195 at the rear wheel. But this isn’t a light switch ride that’s ready to flick you into orbit the minute you twist the throttle. Far from it. It’s just a wicked smooth progression of power that starts down low and just keeps going on forever. It’s a power that is not present in today’s ‘electronic’ bikes. The carburetion is absolutely spot on. No hick-ups… just pull, pull, pull, pull. It takes an expert rider to truly wring this thing’s neck, but it is extremely forgiving. There were a bunch of articles about this particular bike in Sport Rider and Roadracing World back in the day.

“So, as the owner states, it’s not only an amazing bike to ride and exceptionally well equipped but it’s a great story of how the teams and manufacturers were doing WHATEVER NECESSARY to win back in the day!

Some slight liberties have been taken by Buckmaster (or maybe his ghostwriter?) in the part of the description which reads “crushing the competition with Buckmaster at the next 8 rounds on his way to the FX Championship.” Though the Australian may have been on his way to the FX championship, he never quite arrived there: In 2003, Bucky finished second to 19-year old Ben Spies. The year before that, the 2002 championship was in the bag when Buckmaster’s R7-1 broke its crank in the final race at VIR, handing the championship that year to Jason Pridmore’s Attack Performance Suzuki GSX-R1000. (A big crash in practice, Bucky says, probably led to the crank failure.)

God knows the Graves team have won and lost their share over the years, but that defeat, I get the impression, still leaves a bad taste. “It was a potent weapon, scoring every pole position and race win for the first three events of the 2002 season,” writes Chuck. “Really a shame (or sham). I don’t believe that this has ever happened before in professional motorcycle racing, where a bike was legalized for competition 18 months before and then outlawed during mid-season.”

In any case, the bike we’re looking at in this episode of Archive is not that bike! This bike is the street version. What the? I never knew there was a street version until I stumbled upon this one. Yes there was, says Chuck: “That particular bike belonged to Ernie Gutierez and was built in late 2000, before the start of the 2001 season when we were building our team bikes.”

Wait! Actually nobody ever built a street version, ahem, but somebody managed to “homologate” this R7-1 for road use; it’s now a street-going apex predator, complete supposedly with the same 195+ horsepower bored-out 1078 cc R1 motor. The big aluminum fuel tank is dry, and the bike hasn’t run in some time, but judging from the looks of the big Keihin flatslides inside the ram-air fed carbon-fiber airbox, and the sanitary condition of the featherweight fuel tank’s cavernous interior, it appears it wouldn’t take much to reanimate the thing.

Though we didn’t start it up, we did balance the bike on the official MO scales: 383 pounds dry – that’s 5 pounds lighter than what Yamaha claimed for a dry, street-legal R7. That’s pretty light, considering this bike’s packing a musclebound R1 engine in place of the whirry little titanium-rodded 750. The last R1 we weighed, in 2017, came in at about 411 lbs without gas, and made 163 rear-wheel horsepower.

For me, the license plate on this bike makes all the difference. A thing like this is far too rare to ride in anger around a race track, and most of my anger has now entered the acceptance stage anyway. On the other hand, I’d feel equally bad if a bike like this never got ridden at all, as I would watching it cartwheel down the Corkscrew. The happy middle ground, it seems, would be to fire it up on the odd Sunday morning for a quick spin to breakfast and back.

Yamaha made 500 YZF-R7 OW-02’s for the world at the turn of the century. A handful of them came to the US. Chuck’s gone mum on how many R7-1’s he built. Damon Buckmaster’s still pining: “That bike was my absolute favorite. The results I achieved on it ultimately allowed me to negotiate a Yamaha superbike contract, which never quite worked out, as Yamaha’s plan later changed…”

Attack Suzuki GSX-R1000 Formula Xtreme Racer

This has to be the only one you can ride around on in the land of the free. It’s a good conversation starter for a diminishing and select number of race fans who’re now reaching a certain age, who remember the end of the era when roadracing in America was a big deal, and the pre-electronic manly men who rode these things were heroes. For a while there, we were on top of the world.

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

Them was the days. Still have a bit of Smokin' Joe swag somewhere in the garage from the SBK/AMA races at Laguna. I often wonder how good the Go Show might have been.......... I miss bagging on Foggy, even though he was a hella racer. But now we've got MM, so it's all good.

I just read that Peter Hickman raced a hybrid bike at one of this year's IOM events. They combined the frame of his Supersport bike with the suspension of his Superbike.

Definitely not as radical as stuffing a liter-bike engine in a supersport, but the same type of thinking. He didn't win that particular event, but the combo was good enough to podium.