Church Of MO - 2005 Open Supersport Shootout

In preparation of our upcoming 2015 Superbike Shootout we came across this similar gem posted a decade ago. From then to now we find similarities in the entrants as well as the editors, such as Yamaha’s R1 and Sean Alexander. In terms of performance, things have, of course, progressed far beyond what these four machines possessed – mostly in the realm of electronics. “You don’t have a 6-axis gyro, TC, slide, lift and launch control,” asks the 2015 of its predecessor.

First Ride: 2005 Open Supersport Shootout

Thunderhill Park Raceway, CA — Your fingers ache from the strain of holding yourself forward against the vicious acceleration even though it’s only been four seconds since you rocketed off the last corner. The digital speedometer says 154, then 161, then… just a second, as you grab a fistful of brakes and bend the bike into Turn One. The asphalt is smoother near the apex and it takes some extra effort to force your head down to the inside, as your neck muscles fight the 110 mph windblast. You gently roll the throttle on and the bike is happy to stay at the current 45 degree lean angle, but it’s acceleration you’re after and this tire isn’t going to put any more power down unless it’s a bit more upright. That expert club racer with the single-digit number plate is making good time on his four-year-old R1, but you’re catching him fast as you set-up for the long 180 degree Turn Two.

You bare your teeth inside your Arai as you anticipate the pass you’re going to put on him at the exit. He rolls out of Turn Two hard on the throttle, but you’re already deeper and harder into the gas, so you pass him and pull an extra 20 feet diving into the next bend. He doesn’t know what hit him as he bobs in your wake, watching as a brand new machine with turn signals, stock exhaust and mirrors blasts past him into Turn Three.

We all know that it isn’t what you ride; it’s how you ride. At least we knew that up until last week, when testing for this year’s Open Supersports test began. But now, we’re not so sure. You’re probably sick of hearing just how outstanding modern sportbikes have become, as each year sees further refinement of the previous year’s groundbreaking designs. The pace of development has been increasing lately and our 2005 Open Class Shootout makes it clear that the days of resting on your Bold New Graphics are long gone.

To help us determine which bike is the best, we gathered together Suzuki’s all-new GSX-R1000, the reigning MO Champion of the World Honda CBR1000RR, the lightly-updated ZX-10R from Kawasaki, and Yamaha’s venerable R1. We loaded these bikes into our luxurious five-ton crew cab box truck along with leathers, helmets, gloves, boots, tools, cameras, 70’s music, enough tires to choke a horse and departed Torrance for points north.

The track portion of this year’s shootout was conducted at Thunderhill Park Raceway near Willows, CA, where we were graciously hosted by http://www.keigwin.com/schools.htm. Lance Keigwin and his crew are absolutely some of the nicest folks we’ve worked with on a shootout and MO enthusiastically recommends their program as one of the track, we took advantage of the beautiful rolling terrain surrounding most competent and professionally run we’ve encountered. The road course at Thunderhill is a 3 mile, 15 turn roller coaster with several corners that are off-camber and/or blind. It’s a smooth, 36-foot wide racetrack with copious run-off room, fast straights, technical tight turns and an ideal place to thoroughly wring out liter-sized bikes.

On our first evening in Northern California, prior to riding at the Willows to get street impressions of each bike. As it turned out, we got a slightly more adventurous evening ride than we’d planned with rain, darkness, a very large tumbleweed and numerous errant four-legged denizens of the night along for the ride.

After our nighttime blitz in the foothills west of I-5, we were prepared to declare MO as perhaps the most highly qualified publication on the planet to judge the spectral characteristics and brightness of the headlights on this year’s crop of bikes and, along the same lines, the emergency stopping power and agility on wet roads for all four of the contenders.

Our first afternoon (Monday) at Thunderhill was used as a combination sighting session and as an opportunity to circulate the track on OEM tires. Thanks to the folks at Bridgestone, we had ten sets of the brand new BT 002 DOT race tires stashed for when the action heated up. We chose the T3 “medium” compound fronts and T2 “hard” compound rears and eagerly levered them onto our spare rims for two days of racetrack testing. It should be noted that the T2 compound BT 002 is an extremely hard compound that is meant to last under extreme conditions. Since we were going to be swapping these bikes between four riders and lapping them almost continuously throughout the test, we felt it was a good idea to sacrifice outright grip for durability and consistency.

During our two days at Thunderhill, we drew quite a crowd to the north end of the paddock where MO was ensconced for the duration of the track portion of the test. This year we were supported by a veritable army of OEM technicians including Scott “The Stud” Buckley of Kawasaki, Chuck Welch of Suzuki and Jon Siedel, Bob Oman and Doug Toland of Honda. We were joined by Van (aka bmw4vww) Washburn who showed up to lend a hand during the test and several interesting luminaries who stopped by to say howdy.

All good things must come to an end and after an all-too-brief stay in the lush hills of the Northern San Joaquin Valley we had to make tracks back to SoCal to MO’s Torrance headquarters and a rendezvous with our laptop computers. Along the way back, we headed over to Palmdale for a final street impression in the foothills near Lake Elizabeth, then onto LACR for a cold evening of wheelies and three-gear wheel spins down the quarter-mile-long drag strip.

It was a long week, with lots of work (as usual), several friends new and old, almost more excitement that even we can handle, and more fun than any reasonable human being has a right to expect. And at the end of it all, we had a pretty clear consensus as to the winner. So, without any further ado, ladies and gentlemen, the featured event on this card, the 2005 MO Open class shootout. Let the games begin!

The Contenders

4th – Kawasaki ZX-10R

The 2005 ZX-10R is basically the same as the model we tested last year with some subtle changes aimed at suspension and transmission issues we (and others) noted in our evaluation last year. There are new paint schemes in 2005 for the flagship Kawasaki and the pearl red on MO’s test bike was one of the best we’ve seen on a stock motorcycle. At a claimed dry weight of 375 lbs., the current big boy Zed possesses the highest thrust to weight ratio of any of the three returning open-classers.

As with last year the Zed X is very compact (though not as much as either the Honda or the new GSX-R). The frame spars pass over the engine rather than around the sides and the package feels very narrow from the saddle. All of our testers agreed that the ZX-10 felt light, compliant and very agile, and our big guys found it to be among the roomiest of the four. None of us had any huge complaints on the ergonomic layout considering we are, after all, dealing with one in a series of very focused sportbikes.

The ZX-10 is ram-air equipped and the digital fuel injection uses four 43mm throttle bodies, with electronically controlled sub throttles to smooth power delivery, although we wonder if Kawasaki intentionally left some “kick” in the powerband: “The Kawy’s less-linear torque delivery gives it a screaming top-end rush,” says Sean. “It imparts the best impression of riding a booster rocket into low-earth orbit of any bike here. The Suzuki may be slightly faster, but the Kawasaki feels as though it is accelerating harder. Weeee!”

You’d think that this top-end power kick is bad, but it actually helped one tester go faster: “I spent more time revving the Kawasaki up to redline than the other bikes,” say Pete, “and I didn’t feel like I was getting into trouble — I could always tell when it was ‘coming on the pipe’ and was prepared for even harder acceleration. What I mean is that the GSX-R doesn’t seem to have a top-end limit — it just keeps ratching up. It’s not unsettling, it just accelerates so relentlessly that I would unkowningly get into a turn way too fast — and that happended a few times, putting me hotter into corner entry than I felt comfortable going. It doesn’t have a lightning-bolt jolt of power anywhere, it just keeps winding up and up and up.”

Kawasaki isn’t oversizing in this class like they are in the 600s: The ZX-10 engine is a four-stroke, 16-valve, 998cc DOHC inline four with a bore and stroke of 76.0 x 55mm and a compression ratio of 12.7:1. The exhaust system is equipped with Kawasaki’s take on a power valve and a titanium silencer to help the hot noisy exhaust gasses make the transition to the cold, cold world. Similar to last year, the Kawi howled on the MO dyno to the tune of 154.7 horsepower.

The Zed 10’s tranny is a six-speed close ratio unit with multi-plate wet clutch and back torque limiter. Some of our testers noted improved shifting over last year’s model. Clutch actuation is easy and completely transparent, if a bit more abrupt than the Honda and Yamaha. The front brakes are dual hydraulically activated units that grip dual 300mm petal discs via radial-mounted, opposed four-piston calipers. The rear brake is a single 220mm hydraulic single piston unit that puts the clamp to a 220mm petal disc. The brakes work impressively well in hauling the ZX-10 down from triple digit speeds in a hurry. No complaints there.

Up front, 43mm fully adjustable inverted forks handle suspension chores. Rake and trail are 24 degrees and 4 inches. Wheelbase is the shortest of the four at 54.5 inches. The rear suspension features a de rigueur, braced aluminum swingarm with Kawasaki’s UNI-TRAK© linkage system. The rear shock is fully adjustable for everything including ride height. The consensus among our testers was that while the suspension on the 2005 ZX-10 was an improvement over the ’04 model, some nervous behavior remains. No stock steering damper again this year, but the ZX-10 needs a steering damper if you ride the bike hard. Kawasaki provided the optional steering damper for our second day of track testing, which noticeably tamed the frisky nature of the bike when pushed hard on the track.

We asked Russ Brennan of Kawasaki why Kawasaki’s engineers don’t follow the pack and put a steering damper on in the first place. The response? Why include something most riders don’t need? “When we developed [the ZX-10R], the engineers determined a steering damper wasn’t required under normal riding conditions. Trackday riders tend to purchase a steering damper that suits their individual tastes and replace the stock units anyway, so we’re letting the rider make that choice.”

Comparing the steering damper to another component, Brennan made another point: “Last year we were the only OEM to offer a back-torque limiting clutch in this class, which is much more money to purchase aftermarket than a steering damper.” The “accessory” steering damper is an Ohlins unit, but is available directly from your dealer, with a genuine Kawasaki part number (K45104-2005), and carries an MSRP of $364.95. Also required are the $39.95 fork clamp (K53020-364), and a $99.95 frame bracket (11053124). For those of you who are keeping score; this brings the Kawasaki’s “As Tested” price up to: $11,503.85

Another item unchanged from last year is the confusing, poorly lit and hard-to-read LCD tach/speedo combo that we savaged then and shall do so again now. Ergos are reasonably good and the ZX-10 fits tall guys pretty well considering its relatively low 32.5-inch seat height. The six-spoke wheels are notably cool. The mirrors work, the twin headlights are great, and aside from a lot of body- panel rattling buzzing across the rev range, everything about the ZX-10 is tip-top.

The ZX-10R is a thoroughly entertaining ride on the street or the track. On the track, the compact feel and monster motor elicited giggles from our testers, and brought out the MR. ALLCAPS in the meekest among us. It did it with a surprising amount of comfort and civility, yet still had the rough edges that Kawasaki fans demand. Once we added a steering damper to complement the race rubber, it became easier to ride, but surprisingly didn’t really stand out on the racetrack. Is a comfy seat and monster motor enough to edge the ZX-10R into first place?

3rd – Yamaha R1

The wonderful R1 is back unchanged for 2005, it’s the bike that narrowly missed out being the winner in last year’s MO’s comparo. It still has all of the styling (our favorite) and button-down demeanor that makes the big Yamaha a perennial favorite. The Deltabox aluminum frame and well-sorted suspension create a bedrock stable platform. Throw in plush seating, 379 pound claimed dry weight and great ergonomics and it is easy to see why the R1 was a favorite among our testers in ’04. This year the R1, once again, earns particular praise for stability, smoothness, predictable handling and power.

The R1 is fed by dual-valve throttle bodies with motor-driven secondary valves injecting fuel into a four-stroke, 20-valve, 998cc DOHC, inline four. Bore and stroke are 77.0 x 53.6mm and compression is 12.3:1. The exhaust system contains Yamaha’s EXUP and twin underseat titanium silencers. All of this is good for 152.6 bhp on the MO dyno which is pretty darned good get-down-the-road in our book.

The R1’s transmission is a six-speed, close ratio and equipped with a multi-plate wet clutch that is light and transparent in use. The front brakes are dual 320mm discs with forged one-piece radial-mount calipers and a Brembo radial-pump front master. The rear brake is a single 220mm hydraulic disc unit with single-piston caliper. As with the rest of this year’s open-classers, the brakes are a one-finger affair that work in a manner beyond reasonable reproach.

Front suspension is via inverted, fully adjustable KYB 43mm forks. The piggyback rear shock is fully adjustable and attaches to a braced swingarm. Rake and trail are 24 degrees and 3.8 inches. Wheelbase is 54.9 inches. Consensus among our testers was that the R1’s suspension is among the best-sorted (unless pushed to the limit). For most — but not all — of us the R1 was a very easy bike to go fast on and feel good about doing it: “I liked the Yamaha least on the track” said Feature Editor Ets-Hokin, “because it didn’t have the confidence-inspiring precision of the Honda, and it didn’t have the punch or stubby feel of the other two bikes.”

The big guys in our test especially appreciated the roomy ergonomics of the big Yammie while the smaller testers tended to think of it as long and heavy feeling. Seat height is a relatively tall 32.8 inches. One of our testers did note that the R1’s side cutouts make an otherwise relatively large bike easy to handle for shorter riders.

The controls on the R1 are well placed and do what you expect. The mirrors work and are mostly vibe free. The gauges are trick and easy to read and were praised unanimously among our testers. The shift light is the best of any of the bikes that were equipped with one and the tachometer, in particular, is large and easy to read. There is absolutely zero drive train lash in the R1, and the throttle response is absolutely impeccable — everywhere. A couple of our testers singled out the R1 for the cool noises at each end of the bike at full-tilt boogie. Fit and finish are flawless. Ets-Hokin went on to explain his seemingly odd choice for the Yamaha as best street bike: “I picked it as best street bike because it’s the most comfortable, is easy to ride and it feels like the best-built motorcycle: toss in 26,500 mile valve-adjustment intervals and it’s an easy choice for the street rider.”

Once again Yamaha has shoved a worthy entry into the ring. But can the mature R1 open up a can of whoop-ass on its younger and more crazed competitors?

2nd – Honda CBR 1000R

In last year’s open class shootout the clear winner was the RC211V-inspired CBR1000RR. Even though the R1 was close, it was pretty much the consensus of the group that the RR had the goods in nearly every category. Most of our 2004 testers felt as if the CBR1000RR was simply the best sportbike ever – an amazing machine that did everything well. It was also, by a wide margin, the easiest bike for all of us to ride fast straight out of the box. The CBR1000RR was trick, fast, stable, versatile, reasonably comfortable, confidence inspiring in the extreme, and oozed sophistication. There was not a thing on the big RR that did not feel solidly connected to something else. The RR was amazingly lithe and deceptively fast. It returns to the fray in 2005 unchanged.

The RR gets the fuel into its four-stroke, 16-valve, 998cc DOHC inline four via dual-stage fuel injectors. Bore and stroke are 75.0 x 56.5mm and compression is 11.9:1. The exhaust funnels fumes into a trick underseat silencer. Rear wheel horsepower is a class-low 147.11, according to the MO dyno.

The RR’s transmission is a six-speed cassette-style unit with a close ratio multi-plate wet clutch. The hydraulic activation on the RR makes the clutch feel very crisp and precise, perhaps to the point of being a bit grabby (it was the most difficult to launch at the dragstrip). The front brakes are dual full-floating, 310mm discs with 4-piston radial-mount calipers. The rear brake is a single 220mm disc with a single-piston caliper. The brakes at both ends of the big RR are flawless.

The front suspension features inverted fully adjustable HMAS 43mm cartridge forks. Out back the fully adjustable HMAS Pro-Link single shock handles chores without a hitch. Rake and trail are 23.75 degrees and 4.0 inches, respectively. Wheelbase is the longest of the group at 55.6 inches. Numbers aside, the chassis and suspension are rock solid. The 1000RR absolutely plants itself in corners and goes where you will it. The trick HESD (Honda Electronic Steering Damper) puts the clamps on any antics this bike might be prone to at speed. Although a tad undersprung and definitely overdamped for street use, the CBR1000RR is very composed on the track and feels, more than any of the rest of the bikes, like it is an integrated piece of machinery designed from the ground up to work as a unit: “The Honda is a great ride,” notes Sean. “No quips about it — it’s stable, and unintimidating. It genuinely has a great chassis, and a brilliant steering dampner which allows it to be less intimitading than the other bikes.”

The riding position of the big RR is one of the more cramped among this year’s class of bikes. The seat height is 32.5 inches, the pegs are high and the clip-ons are low. Still, it’s not as much of a chore to ride as, say, the GSX-R, and one of our smaller testers found the riding position very comfortable. The weight of the 1000RR (claimed dry weight is 396 lbs) is a non-issue from the saddle thanks to very compact dimensions and mass-centralization.

Because nearly all of the power that the big CBR makes is usable, thanks to its supremely stable chassis, long swingarm, spot-on throttle response and reassuring suspension, it’s very easy to ride. The intake honk and exhaust notes are as sonorous as a Formula One car, especially near the top of the rev range. The CBR1000RR is an amazingly competent motorcycle that exudes refinement and quality, and fit and finish are typical Honda perfection.

Similar to the CBR600RR, the 1000RR seems to be stable, user-friendly and confidence-inspiring both on the track and on the street. Of course, it doesn’t hurt when Honda sends World Endurance champ Doug Toland to help tune the suspension, but we think it would have that feel anyway. On the street, the Honda was pretty unpopular with our testers, mostly for the rock-hard seat and low bars. Only our “million-mile man” Pete Brisette was able to look past the seat-like object mounted to the frame to appreciate the all-around balance and smooth motor. As he says in his summary: “You can remedy the seat situation, [but] it’s awfully hard to fix engine buzz.” The Honda’s refinement, ease of use and flexibility make it a sure contender for best overall package.

1st – Suzuki GSX-R

All new for 2005, the GSX-R1000 was the great unknown factor going into this test. The new Gixxer is so compact it looks like a 9/10 scale model of the rest of the open-classers. The styling is radical and edgy, but its puppy dog friendly single headlight seems to wave with a reassuring “Hi” that breaks the ice, even if the next word in the phrase has a chance of being “side”. At a claimed dry weight of 365 lbs. it is the lightest by a fair margin of the four bikes. You’ve heard it a million times, but this new Gixxer is truly the first open-classer that can boast of liter bike performance in a package of supersport dimensions and feel.

To any regular sized rider the G1K feels tiny. It’s narrow, has the lowest seat height of the group at 31.9 inches, and very high pegs. Mercifully the reach to the clip-ons is shorter than in previous iterations of the GSX-R. Nonetheless our taller testers looked like trained bears riding tricycles in a circus ring when riding around the track on the GSX-R.

The new GSX-R breathes through an improved electronic fuel injection system featuring the Suzuki Dual Throttle Valve System (SDTV) that maintains optimum air velocity in the intake tract for smooth low-to-mid rpm throttle response and high torque. This system feeds air to 43 mm twin injector throttle bodies for improved throttle response and acceleration. The primary injector operates under all conditions while the secondary injector operates under high rpm/heavy load. The new engine is a 998.6 inline four with 16 titanium valves. Bore and stroke are 73.4 x 59mm and compression is 12.5:1. Lighter valves and pistons along with several tricks aimed at reducing internal friction result in a red line that is 1000 rpm higher than last year’s GSX-R1000. Exhaust gasses flow through the new Suzuki Advanced Exhaust System (SAES), an all titanium unit designed and positioned to keep mass low and close to the centerline of the bike. The funky triangular silencer allegedly decreases drag and definitely increases cornering clearance. The SET power valve remains.

The Gixxer’s transmission is a redesigned six-speed close ratio unit with multi-plate wet clutch and back torque limiter. As with the rest of the test units, the clutch is transparent in operation. The front brakes are bigger, 310mm dual discs with radial-mounted, four-piston calipers and a new radial-mount master cylinder for improved lever feel and feedback. On the rear disc is a single-piston caliper. Braking is excellent, with drag-chute power tempered with delicate, sensitive feel.

Suspension is via fully adjustable 43mm inverted fork with Carbon (DLC) coated stanchion tubes to reduce friction. It works, as there is virtually no stiction apparent in this unit. Rake is 23.8 degrees and trail is 3.8 inches. Wheelbase is 55.3 inches. The piggyback rear shock is fully adjustable with a more linear rate than its predecessor. The new braced aluminum swingarm is lighter in weight, more rigid, and the right side is shaped to help tuck in the Electrolux exhaust canister.

Of course the big question is how much juice does the new GSX-R put out? And (drum roll) the answer is – a Hoover Dam-like 158.7 bhp with enough torque to turn the screw on an Ohio class nuclear submarine. Thus, the ’05 GSX-R1000 is currently the best candidate for the X-prize for two wheels with aftermarket bolt on wings.

So the new GSX-R is evidently everything the pre-release buzz had it hopped up to be. It’s small, agile, very light and has class-leading power. Fit and finish are excellent. The GSX-R abounds in useful features that will appeal to club racers, and for those who care about such things it is undoubtedly the closest of the four bikes to being race-ready right off the showroom floor. Aside from the fact that the ergos will torture taller riders it seems to be absolutely the bike to beat this year. As a final raised digit directed toward the competition, the 2005 Gixxer also has the coolest soundtrack among the inline four liter bikes and one of the better ones in all of motorcycledom.

So how does the uberhünde GSX-R 1K compare to the rest? The whole greater than the sum of the parts, or less? “Take the best features of the Honda, Kawasaki and Yamaha, put them together and you have the 2005 Suzuki GSX-R1000,” says Sean. “It has no bad manners, and a really big {explicative deleted}! The Honda’s friendliness and stability, the Kawasaki’s top-end rush and the Yamaha’s bad-ass intake snarl, the Suzuki’s got them all. Unless you just don’t like Suzuki, I can’t think of a reason why you wouldn’t be happy — if not a bit overwhelmed.”

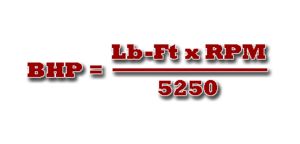

Tech: Area Under The CurveAfter having ridden these bikes for a few days it’s no secret to any of us that the GSX-R1000 is the class leader in power. After one ride, anyone’s seat-of-the-pants power gauge can tell you that, and we confirmed this on our DynoJet model 250 Dyno. But what, exactly, is the proper way to know which bike is truly the most powerful? Peak horsepower? No. Peak torque? No. In both cases, a narrow-band spike of power can sway the numbers. What you want to look at is the area under the curve (one can use a plotter, MS Excel, or the thinking man’s way is via a simple integral, although it can be profusely argued that the real thinking man’s way is to have graduate students do it). Look at those nice lines drawn across the dyno charts, it’s the total area under that curve that is meaningful — basically, it’s the total volume of power produced.Torque, in a nutshell, can be thought of as big lever — the longer the bar, the more leverage. Here, the GSX-R clearly reigns supreme, besting the R1 by 12.7 percent, the Honda by 13.9 percent and the Kawasaki by 13.9 percent. That’s it, that is the outright difference in power measurements for these engines. But this is somewhat misleading in the real world, and here’s why: Transmissions are just torque reducers. The “taller” a bike is geared, the more the torque applied to the ground is being reduced — you’ve got a shorter lever (more so with each upshift).

For instance, to go a mile a minute, a 1,500 rpm Cummings diesel truck needs significantly “taller” gearing than a Kawasaki Ninja 250 screaming along at 12,000 rpm. Think of the truck’s transmission as a shorter lever and you’ve got the right idea: the amount of torque being applied to the ground at any given instant that’s going to determine how rapidly you can accelerate. It’s all down to those torque-reducing transmission again (technically for you sticklers, multiplying less, except in Harley-Davidson Sporter Transmissions’ fifth gear, which is 1:1 and is why they make more power in fifth — 1:1 gear ratio means less frictional gear loss — this is why we insisted our 90 bhp spec racebikes were always dyno’d in fourth gear, but we digress). Every time you upshift, you’re reducing the effective torque that can be put on the ground. Torque is either multiplied or divided. If you have a 10:1 final drive gear ratio, torque is multiplied by a factor of 10. If the engine produces seven ft-lbs of torque at the crankshaft, the transmission will output 70 ft-lbs to the rear wheel. If you have a lower-revving engine that only turns half as fast, it’ll need a 5:1 ratio to go the same speed, so it will only output 35 ft-lbs to the rear wheel.

So why is torque so important? Want move big heavy things really slowly up long hills? Get an engine with a ton of torque and give it a long lever — a really short transmission like the 13-speed ones in big diesel trucks. It’s not going to go fast, but it has the outright power to move the weight. Ultimately, the power a little Ninja 250 can put out is very limited so even with the shortest of reasonable gearing you just can’t lift tons of load — at least not with any expectation of getting over the top in this lifetime, let alone with angry SUV drivers behind you!

So why is horsepower so important? Because motorcycles are relatively light, and since we want to move them quickly over a period of time we need a way to measure torque with relation to time. This is where horsepower comes in — it’s a mathematical representation of torque and time divided by a constant. So a motorcycle should, theoretically, make the same amount of horsepower in any gear. Since we want to get places quickly on our bikes, measuring the area under the horsepower curve is a good indicator of that. Here, the GSX-R still shines, besting the R1 by 12.6 percent, the ZX-10R by 11.6% and the Honda by a whopping 18.7 percent.

Comparing area under the curves of the torque vs. horsepower graphs is very enlightening and much insight can be gained about the bike’s real-world characteristics. Look at the Honda, in area under the torque curve, it’s only 13.9 percent behind the class-leading Suzuki. But it lags by 18.7 percent in the horsepower arena — this means the Honda makes more of it’s power down low. Conversely, the Kawasaki trails the Suzuki in torque area by 13.9 percent but gains more than two percent horsepower (11.6 percent down) versus torque as compared to the Honda, which loses 4.8% — and you can tell that the Kawasaki makes more power at higher rpm and will have more of a top-end “rush”, while the Honda would be classified as “more tractable.” It’s no surprise that the Honda was the least-frightening engine on the track, this and its stable front end gave it the outright track victory. The real speed freaks like Sean will want the Suzuki but will also get a kick out of the Kawasaki’s lunge. For the newbie, a flatter torque curve will have an easier learning curve.

Let’s look at this a little more, and consider more generalizations of low-horsepower versus high-horsepower bikes of the same displacement. Torque shreds things. Remember that horsepower is a function of rpm, so in order to make more bhp with the lightest possible parts, you want to rev the engine higher. Indeed, to rev the engine higher, you need lighter parts. One compliments the other. You can see why spinning things higher and higher is so important: 75 ft-lbs of torque at 5,250 is 75 horsepower, but 75 ft-lbs of torque at 10,500 rpm is 150 bhp. A lot can be gained by simply shifting the torque peak higher. Put another way, think of horsepower as that long torque lever spinning. Think of a higher-horsepower engine as that long lever spinning much faster and — given the same length of that lever — you’re going to make more horsepower in the later, faster-spinning scenario. In many cases, it is more advantageous to spin that lever faster than it is to make it longer — because it’s got to be stronger to be longer, you have to make everything else stronger to support it, thus things tend to get heavier.

Another example: Start out with a lower-revving bike and you need taller gearing to go the same speed, thus your basic design has you starting out with less available torque on the ground. Take any motorcycle, put it in first gear and measure the acceleration vs. the acceleration it produces in sixth gear and first gear wins out every time. Think of it like this: drag race two of the same bikes from 0-60 mph, one bike using first through fourth gears, the other using third through sixth gears. The former — the higher-revving bike in our analogy — is going to win every time because it’s putting more real power to the ground by not reducing it so much via the transmission.

In closing, if you really want to know which bike is fastest — outside factors such as weight, wind drag and friction being equal — we want to look at the area under the curve of the all-gear dyno runs, using the X-axis to mph instead of rpm. This will tell you the theoretical winner of any zero-to-whatever-mph race you want to run. Look for MO to be doing the math in future features.

–Martin

ALL TORQUE

ALL POWER

Conclusion

We’ve told you about each of this year’s superb crop of open class bikes from technical descriptions to our individual perspectives of their performance on both the track and the street. We’ve described our testing methodology and told you how much fun we had doing all of this. Now it’s time to give you our rankings. But first, a proviso: Even though there is always a winner in MO shootouts we feel that this year’s crop of liter bikes are among the best and most closely matched we’ve seen. The quality and craftsmanship in each of these bikes is unbelievable. Thus, choosing among them becomes somewhat of a subjective matter of taste.

Yes, a couple of these bikes do dominate based purely on the stat sheets. But having ridden each of them at length we believe that each of these superb bikes was a legitimate contender for the title of MO open-classer of 2005. We’ve said it before: one does not ride a spec sheet down the road. In the flesh each of these bikes are endlessly competent and all of them have a wonderful character of their own. For 2005 Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha have succeeded in crafting bikes that are so advanced and are of such high quality that each is absolutely the best bike in the world for someone.

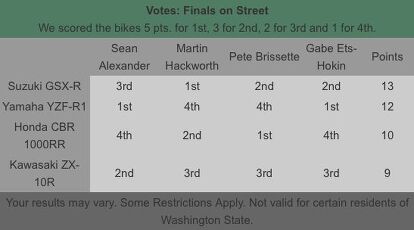

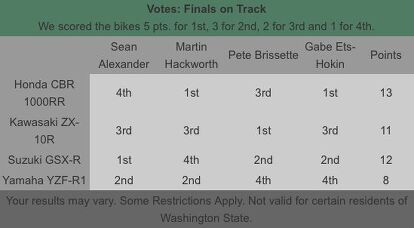

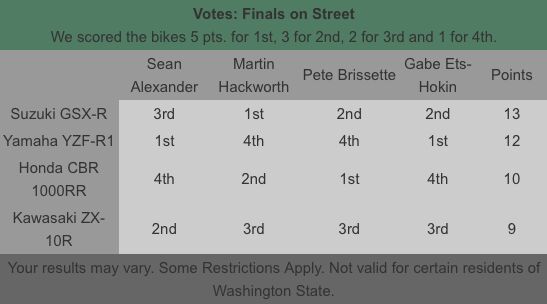

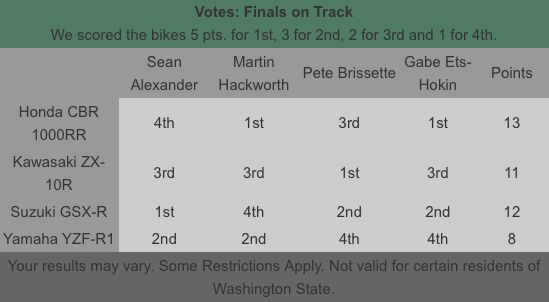

We’ve made our choices for this year and we hope that the information and perspective we have provided is helpful, or barring that, at least amusing. We’ve ranked the bikes based on both their street and track performance. Since most of you are not racers, and since the overwhelming majority of these bikes purchased will never see a racetrack we biased the rankings in favor of street performance by a ratio of 2:1. We used a weighted scale for individual rankings with 5 points awarded to a testers first choice, 3 for the second, 2 for the third and one for the fourth. The final rankings are below.

As you can see the track rankings are very close, with only one point separating the CBR1000RR, the GSX-R1000 and the ZX-10. The Honda comes out on top here by virtue of its rock-solid stability and ease of use. Congratulations to Big Red.

On the street the wildly fun GSX-R1000 simply blew the doors off of the competition. “If you can get past your fear,” says Sean, looking very analytical after turning a blistering 2:03 on the big Suzuki, “the Suzuki does everything as well as the other bikes, and throws in significantly more motor to boot. If you have aspirations of winning club races the GSX-R is it — both in production and modified because it’s the best platform start with. I’d bet a buck that a stock GSX-R is fast enough to win, even in the modified classes.”

Yes, MOFOs, the 2005 Suzuki GSX-R1000 is the most fun package that terrifying power comes in. Notice that even if we had weighted the track and street totals 50/50 the GSX-R would have still won the shootout going away. So the undisputed winner of the MO 2005 open class shootout is the Suzuki GSX-R1000. Hail to the king!

| “Put My Money On The Table” Table How the testers would spend their own money. We scored the bikes 5 pts. for 1st, 3 for 2nd, 2 for 3rd and 1 for 4th. | |||||

| Sean Alexander | Martin Hackworth | Pete Brissette | Gabe Ets-Hokin | Totals | |

| Suzuki GSX-R | 1st | 3rd | 2nd | 1st | 15 |

| Honda CBR 1000RR | 3rd | 1st | 1st | 4th | 13 |

| Yamaha YZF-R1 | 2nd | 2nd | 4th | 2nd | 10 |

| Kawasaki ZX-10R | 4th | 4th | 3rd | 3rd | 6 |

Deep Thoughts

Martin Hackworth’s Final Thoughts:

If I were going to drop somewhere north of ten large on any of these bikes it would be the Honda CBR1000RR. I was fastest on it on the track because it was the most stable, the most reassuring, and the easiest to ride. Street performance is less of an issue for me with modern liter bikes because I think that they make only fair platforms for the type of street riding that I do. None of the 2005 open-classers are suitable for extended road riding so the track performance would be the primary factor in my purchasing decision. Honda’s excellent reputation for reliability and their high engineering standards would factor in as well. I’ve owned several Hondas and they just plain work.

I’d give the R1 a hard look as well. It’s nearly as fast, easy to ride, and stable for me and makes even a better street bike, though still far from my ideal. The R1 is just not quite as polished as the Honda, but it’s pretty close. It’s a lot more comfortable to live with as well. It’s a very close second.

The GSX-R1000 and the ZX-10? Toss a coin into the air. Both are great hooligan bikes and put you at the top of the boulevard GP, but that’s not anything that I have a high degree of interest in anyway. Both are great motorcycles, but not what I’d spend my son’s college tuition on.

Racer Girl: Elena MyersYou see a tremendous variety of riders at trackdays, from the 60-year old banker on his MV Agusta to the younger guy trying to de-squidify by “taking it to the track”. You also see a lot more women riders on the track than you did 10 or even five years ago.However, seeing a 12-year-old girl on a 125cc GP bike was a little surprising! Elena Myers is a regular at the Stockton Motorplex and other Super Motard tracks in California, with strong finishes in the Super Lightweight class on her tricked-out RM80 motard bike, as well as in California’s Mini Road Racing league.

Armed with a sponsorship from Umbrella Girls USA, Elena’s dad Matt Myers (who runs the Stockton Mini Road Racing Club) purchased a 1997 Honda RS125 GP bike and treated it to a trick, hot-pink paint scheme. On Elena’s first track outing in February of 2005, she turned some impressive times at Thunderhill park, besting my best times there by a second!

On the day we were there, Elena was looking especially smooth and fast. She was turning 2:08’s, only seven seconds a lap off a winning pace. She’ll be running her RS125 in select CMRA and WERA races this season, and she looks forward to the change from dirty Super Moto to cleaner, faster Roadracing.

“Everything’s different” going from dirt to roadracing, when I asked her what was different about riding on a big track. “It’s easier.”

— Gabe

Money Man Sean Lays his Money Down:

Joy! I just received a hypothetical check for the exact purchase price of any bike in this test. What to do? This is a hell of a dilemma. The Honda is super stable with its awesome HESD damper inspiring confidence and piece of mind as I probe its limits. Of course it’s easier to inspire confidence when you have the weakest acceleration in the group. On the other hand, the ZX-10 has a nice comfy seat and a killer top-end rush, but it continues its head wagging ways, unless I spring for the optional Ohlins steering damper.

This leaves me with the GSX-R and R1. I love the R1 for its beautiful intake noise and the way it shudders and almost shakes its head, without actually doing anything too scary. It feels fast in a most entertaining way and the beautiful gauges and world-beating styling make it a strong candidate for my purchasing dollars.

However, there is no way to overlook the total package that is Suzuki’s 2005 GSX-R1000. The new GSX-R combines the Honda’s stability, exceeds the Kawasaki’s power and has an intake noise almost as intoxicating as the R1’s. If I were looking for a street bike the R1 would probably win out. The Suzuki’s best thing on the street is that it has the least amount of suspension stiction, so it gives a little more of a compliant ride, and the worst thing is its abrupt off/on throttle transition, which exacerbates the little bit of drive lash that it has. This is only noticable at really slow speeds, like in the parking lot when you’re looking for a spot, or cruising around pit lane at a track day — once up to speed, the problem vanishes. However, for a race or track day weapon, the GSX-R has no equal and it earns my overall vote because after all, these bikes are meant to be used on the racetrack.

Million Mile Man Pete Brissette Sounds Off:

If you’re part of the overwhelming percentage of riders who’ll never take your bike within a ten mile radius of a race track let alone get on a track but do plan to wear out the odometer you’ll have some strong opinions too. For anyone who fits the above description of a rider you’ll undoubtedly be looking for balance in design but be uncompromising in your expectations of quality. If that in fact is you than consider yourself “in the know” with me about the Honda CBR 1000. It’s the best blend of all that a liter bike can and should be, refined in every way. Big Red has kept the motorcyclist who demands it all in mind when they crafted their entry in the liter class war.

The R1 and CBR are the two bikes with the most to prove. Honda has set out to do just that by proving Abe Lincoln wrong and trying to please all the people all the time. Here’s how they did that in a nutshell: Wide clip-on placement to allow for a more relaxed position and great leverage at the same time; little if any vibration transmitted to the rider thru the foot pegs and handle bars; overall ergonomics that will allow you to dismount without feeling dismembered; an engine that has more than adequate power but delivers it subtlety; two- finger brakes with the clamping power of a ten-ton press; the utter definition of stability by way of its frame and the now standard-setting HESD steering damper. Legendary Honda refinement wraps it all up into a great package.

The R1 needs to take some lessons in the people pleasing department. For instance, how not to keep the rider’s tushie nice and warm. If I noticed the heat in 50 degree weather how much more of a problem will it be in the blazing heat of August? Clip-on placement isn’t particularly wonderful either. Combine that with enough engine buzz to qualify as a sufficient numbing agent to prepare me for surgery and all I could think about was how much I wouldn’t own this bike just because of that one drawback. It has a super-slick transmission and is the best looker in the test, but too bad Yamaha didn’t use that attention to detail in some more crucial areas.

Suzuki has done some people pleasing of their own. But it’s more for the riders who go from here to there with as much exhilaration as possible in as little time as possible as opposed to the riders who need to go from here to there and then over there and then back over here again one more time because you forgot something. The overall impression is that the Suzuki is a race bike with D.O.T. required turn signals and license plate.

The Kawasaki ZX10 falls just on either side of the extremes. It’s a perfectly good bike in its own right but when the margin of separation is so narrow the slightest flaw will stand out. The tall seat, buzzy rattle from the engine bay and lack of a steering damper means the Kawi’s plusses don’t add up enough to beat the Honda, even though it has the plushest seat in the class. But this is a minor inconvenience with the Honda: you can remedy the seat problem by scouring the aftermarket, but it’s awfully hard to fix engine buzz.

So, if you consider yourself a member of the Million Mile Club, then you’ll understand my assessments as fairly accurate and valid. And if you want to be a charter member, let the 2005 Honda CBR 1000 take you there.

Gabe’s Final Word:

It’s a cliché now for magazine editors to say that any one of the latest sportbikes would be a good choice for almost anybody, allowing us to weasel out of picking a winner, but when you ask us to put our hypothetical money on the line, you suddenly see strong opinions come forth.

All four of these bikes are incredible machines I would happily own. However, if forced to choose, I would pick the GSX-R1000 to spend my money on. It’s almost the most comfortable on the street, has the best brakes, and has the lightest feel of all the rest. And when you add the most amazingly tractable and powerful engine I’ve ever experienced in a motorcycle, the choice becomes easier still.

The Honda worked better for me on the track, but its street comfort is questionable. The R1 feels like the best engineered machine, but it’s big and a little slow compared to the ZX-10R and GSX-R. (I feel like a crazy person for writing that!) The ZX-10R feels tiny and has a great motor, but it’s just a little rough-and-tumble for me to spend $11,000 on when presented with a choice.

I voted the Yamaha last on the track, because the Honda gave me more confidence, the GSXR felt much faster and the ZX-10R was more fun and manageable with the steering damper. It’s a very nicely engineered machine that is a quality piece of equipment, but the other three felt like better bikes for the track.

I picked the R1 as best street bike, because it’s the most comfortable and it feels like the best-built motorcycle, which is important if you are investing this kind of money to purchase transportation: a 26,500 mile valve-adjustment interval is something to take very seriously, especially for a high-mileage rider. Fast, fun, comfortable and easy to ride: this makes it an easy choice for the street rider.

Spending $11,000 to buy one of the most powerful, best handling motorcycles on planet Earth is not a rational thing to do unless you’re a club racer, which in itself is one of the least rational things to be. So for those of us about to plunge ourselves into financial insolvency to buy one of these crazy things, the decision should be tempered with a good-sized dose of irrationality. The GSX-R is the choice of the unhinged genius. It’s a fabulously designed machine that is designed to be imperfect in a charismatic, friendly way. It’s like hanging out with your dangerously crazy friend who somehow has a good job and a happy marriage.

The boys and girls at Suzuki deserve big kudos for thinking out every last detail on their new 1000 and delivering an excellent-handling, supremely engineered motorbike with a monster motor that would have been at home on a WSB grid seven or eight years ago. It should get bike of the year, and would definitely get $11 grand of my money, if I ever actually had 11 grand!

| Thunderhill Lap Times | ||||

| Martin Hackworth | Gabe Ets-Hokin | Sean Alexander | Avg. Lap Times | |

| Honda CBR 1000RR | 02:20.5 | 02:13.6 | 02:07.6 | 02:13.92 |

| Kawasaki ZX-10R | 02:21.1 | 02:14.9 | 02:03.9 | 02:13.32 |

| Suzuki GSX-R | 02:23.0 | 02:13.9 | 02:03.4 | 02:13.44 |

| Yamaha YZF-R1 | 02:20.9 | 02:18.2 | 02:05.2 | 02:14.76 |

| LACR Dragstrip | ||||

| Martin Hackworth | Sean Alexander | |||

| Honda CBR 1000RR | 11.79@126.8 | 11.04@128.8 | ||

| Kawasaki ZX-10R | 11.50@128.1 | 10.70@133.2 | ||

| Suzuki GSX-R | 11.64@128.2 | 10.61@132.7 | ||

| Yamaha YZF-R1 | 11.76@128.2 | 10.85@133.38 | ||

A former Motorcycle.com staffer who has gone on to greener pastures, Tom Roderick still can't get the motorcycle bug out of his system. And honestly, we still miss having him around. Tom is now a regular freelance writer and tester for Motorcycle.com when his schedule allows, and his experience, riding ability, writing talent, and quick wit are still a joy to have – even if we don't get to experience it as much as we used to.

More by Tom Roderick

Comments

Join the conversation

For the love of Pete Brisette! You forgot the next 5 pages!

This was my first time really riding open-class supersports, and it was an incredible experience. Lots of good memories from that 3-day trip to Thunderhill from Torrance--making fun of Martin, weird discussions with Fonzie that always made sense at the time, dicing with Petey...good stuff!

Sean wrote this story (I think), but I recall helping him write the intro in the van as we drove to dinner in Willows. He somehow was able to type and drive.

'“You don’t have a 6-axis gyro, TC, slide, lift and launch control,” asks the 2015 of its predecessor.'

Well, that's true of the R1. If the gixxers met all the old one would say to its younger sibling would be "Wow, sweet special edition paint job, bro!"