Church of MO: Sport Twins 1997

If it’s 2022 then 25 years ago must’ve been 1997, when Motorcycle Online was still trying to gain traction in the moto mediaverse. Probably not helped along by Editor Plummer writing that new riders should skip the Suzuki TL1000 and just go straight to the morgue. There were videos of the Sport Twins in action, though, which seem to have been lost in the sands of time, but must’ve been a treat to watch over your dial-up modem. The Suzuki did well in this little comparison in spite of the abuse, but I can’t remember the last time I’ve seen one. The SuperHawk on the other hand, has become a bit of a cult favorite, and still warms the old cockles occasionally.

Where’s the Duck?

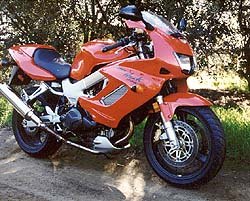

Super HawkV-Twin fans have been begging Honda for a larger version of the discontinued 650 Hawk GT since that model’s introduction in 1988. With the VTR1000F, Honda has finally given them what they wanted. While the Hawk used a traditional beam-style frame, the VTR is equipped with a combination of aluminum beam and trellis frame to support its new mill. Honda engineers have stated that rear wheel input to the chassis can cause front wheel instability in a typical beam frame design — an “echo effect.” Thus, Honda claims the VTR’s frame has been designed to cancel this problem. Does it work? We guess so — the Honda is much more stable that Suzuki’s TL1000.Honda shines in other areas, too, notably the styling department. Its attractive fairing — which resembles the upper unit from a CBR-F3 — is far better looking than the Suzuki’s Ducati imitation. Similarly, the VTR’s nicely sloped tail section is miles ahead in terms of styling than the pimple-shaped unit on the TL.

Different design philosophies between the two manufacturers are apparent the first time you swing a leg over these bikes. Suzuki’s TL folds its pilot into an aggressive riding position with high pegs and clip-ons mounted under the triple clamps. Honda’s VTR, while still sporty, features a more upright riding position, is a little more roomy and places less weight on the rider’s wrists. Sitting on the Honda for the first time is quite surprising: With its twin side-mounted radiators and slim frame, the VTR feels more like a bike half its size.With ten fewer ponies than the TL, a longer wheelbase, lower seat height, and a more rearward weight bias, the VTR isn’t as wheelie prone as its Suzuki rival. This isn’t to say the Honda isn’t capable of such antics, however, because an extra twist of throttle and snapping of the clutch will send its front wheel skyward with ease. But the Honda’s smooth, linear powerband makes it feel far less potent than the bucking TL, and it is: At Los Angeles County Raceway our VTR clicked off an impressive 10.83 second quarter-mile at 127.32 mph, compared with 10.53 at 133.06 mph for the TL. This may not sound like much, but 3/10ths of a second in the quarter mile means one bike “walks away” from the other.

Throw in some curves though, and the margin closes. During our racetrack testing at The Streets of Willow, the VTR trailed by less than a second. Although the Honda’s 41mm fork is 2mm narrower and lacks the compression adjustability of the TL’s inverted unit, it tracks through both slow and fast corners with a remarkable sense of stability. Out back, its rear damper is also devoid of compression damping, yet manages to do a decent job of soaking up pavement irregularities, as long as speeds aren’t too high. When the going gets fast, the VTR’s soft, street-based suspension, chassis flex and limited ground clearance becomes a concern. Honda makes no bones about this, though. They’ve clearly stated the VTR’s mission in life is not to be a racing platform. They would rather trade off that extra edge of track performance for real world comfort. We think they’ve succeeded.

What we have here is a bike that can almost hold its own at the racetrack and dragstrip, is great fun around town, commuting or on the freeway and a blast to ride in the canyons. But in this test it finishes second. What gives? Suzuki’s TL1000, that’s what.

1. Suzuki TL1000S

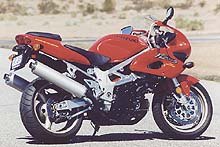

A view to a kill: Send Shawn Higbee out for some “exciting video footage” and he gives us an on-board highside flic. Maybe we should’ve been more specific…While Honda already has a history of V-Twin sportbikes, Suzuki is working with a fresh mold. Although judging by the looks of their frame, headlights and fairing, they did have some Ducati blueprints to work with. Too bad they didn’t copy the 916’s seductive tail section though.

Once the fashion show is over — and we’re all done gagging — we’re ready to ride. Thumb the Suzuki’s start button and immediately you’re rewarded with a pleasing mechanical medley from its chain/gear driven cams that invites mindless throttle blipping at intersections. Click the six-speed gearbox into first, give it some gas, let out the clutch and, if you’re like us, the bike stalls. Below 2,500 rpm, Suzuki’s fuel-injection isn’t mapped out as well as we would like — a problem compounded by an ultra-light flywheel — causing some awkward moments.Once you’ve successfully pulled away and have found a wide open stretch of pavement you’re in for a treat. Wringing a TL to redline is an experience not to be missed, and not for the faint of heart. With 114 horses on tap and an arm-stretching 72.6 ft-lbs of torque, the TL rockets forward with the velocity of an open-class sportbike. Plus its lofty seat height and short (55.7 inch) wheelbase combine to make the TL a wheelie monster. Accelerating hard through first and second gears will loft the TL’s front wheel every time, making for constant grins on twisty roads where the TL pilot can square off a corner and wheelie to the next.

Suzuki’s TL is also an excellent weapon for racetrack use. With its steep steering head angle and short trail (23.7 degrees and 3.7 inches, respectively), it eagerly flicks into corners. The TL has more weight biased towards its front than the VTR, making a TL rider more in touch with what the front wheel is doing. Out back, Suzuki’s rotary shock does a good job of soaking up bumps, although our testers generally felt it didn’t perform as well as a conventional unit. Initial concerns about where TL owners would turn if they didn’t like the shock’s damping may be dismissed, as at least one aftermarket company has plans to market a unit for the TL.

When it comes to comfort, Suzuki’s TL isn’t that far behind the Honda, although one of our taller testers hated the squared-off, wide tank that puts pressure on the inside of his legs. As a pure streetbike, the TL can’t match the VTR in the comfort zone, but it shouldn’t be pegged as an unridable race-replica either. Droning along the freeway for a couple of hours is no problem, although commuting in today’s urban traffic will hurt your wrists (unless you’re riding wheelies the whole way, but that’s illegal, and you wouldn’t do that, would you?).Bottom line? While Honda’s VTR is a smooth, comfortable sporting motorcycle that is also pretty quick around a racetrack, Suzuki’s TL is a powerful, rowdy canyon carver with an excellent chassis that’s damn close to a 916 in terms of feel and handling. And it’s also not too bad in the real world of traffic and freeways. You can weight your opinion where you like, but for our money we’ll take the sharper sportbike – Suzuki’s TL1000S.

Technical Overview: Suzuki TL1000 Rotary ShockRotary Dampers: The Coming Trend, Or Exotic Screen-Door Closer?

By John Olsen, Contributing Writer

So what’s up with Suzuki? This relatively quiet company, noted for occasional flashes of brilliance followed by long periods of technical sleepiness seems to have become a technological Godzilla. Recent examples include the dominant redo of their GSXR-750 and its smaller brother, the GSXR-600. And perhaps most astonishing of all, the TL-1000S with its upside-down forks and fuel injection. This Ducati 916 clone provides, at least on paper, most of the cutting-edge technology of the vaunted 916, but at 9/16ths the cost.

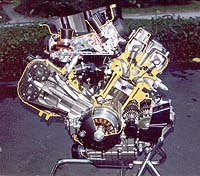

One technological feature that might help Suzuki compete with the all-conquering Ducatis is the novel rotary damper. Suzuki chose to separate the functions of springing and damping for this motorcycle. Why blaze a seemingly new path – a path that could be littered with unknown land-mines? Why not stick with the well-understood blessings of today’s universal sport-bike rear suspension — the linkage-actuated, coil-over-damper, single shock rear end? After all, the status quo ain’t bad.

An obvious answer lies in a central problem of modern motorcycle design: Packaging. The latest school of race-bike design calls for much of a bike’s weight to be carried by the front tire and for a short wheelbase that works with a steep steering head angle to give quick handling. Get enough weight on the front tire, and you gain several vital advantages: The bike can accelerate harder without wheelying, allowing steering corrections under acceleration. Also, the more weight the front tire carries, the harder it can be turned without exceeding reasonable slip angles. A longer wheelbase increases a bikes turning radius, meaning more lean angle is required to maintain cornering speed. Also, rider inputs or bike responses to bumps happen more slowly.

A longitudinal, 90-degree V-twin, like the TL, any twin Ducati, or the Honda VTR1000, presents a packaging challenge. Rock the engine forward, and you run into clearance problems between the front wheel and radiator. Rock it back, and the rear cylinder takes up valuable volume that could be used for the battery and the electrical system, or the shock absorber. The result is that 90-degree V-twin sport bikes tend toward the long side, with the TL and 916 shortest at 55.7 and 55.6 inches, respectively, and the VTR and the 900SS at 56.3 and 56.4. The VTR tries to minimize the wheelbase penalty by running twin side-mounted radiators, allowing the engine to come as far toward the front tire as fork travel and flex allow.

Suzuki achieves a relatively forward weight bias and a moderately short wheelbase by clever engine and head design (the cam drives and cam layouts in the heads are specifically designed to permit the engine to live closer to the front wheel). Also, placing miscellaneous stuff in the space where Ducatis and Honda place their rear shocks allows for a tighter, trimmer package.

So where does the shock go? Suzuki, teaming with Kayaba, opted for a solution that has actually been used before in huge numbers — the lever-actuated, rotary-acting, hydraulic shock. While many people will credit Suzuki for inventing this design, a damper of similar concept, the Houdaille, has been used on vehicles ranging from sports cars to trucks since the early days of damped suspension.

Suzuki’s rotary shock gives them some advantages in addition to a shorter wheelbase. One is heat dissipation. Perhaps the major enemy of any damper design is heat build-up. Damping is just conversion of some of the mechanical energy generated by the motorcycle bouncing on its springs into heat energy. Since hydraulic fluids and rubber seals can’t operate at high temperatures, this heat has to be dissipated, or the damper will work poorly.

The TL’s aluminum damper body has more mass than a tubular shock, and this mass in itself will absorb heat from the damping fluid until it is just as hot as the fluid. In fact, early testers report that the damper stays cool to the touch, even during hard track sessions, something you can’t claim for the typical tube shock design.

Relative motion between the moving parts in this damper consists, obviously, of rotation. Two good things happen with rotational, rather than telescoping, motion: Rotating joints between the damper body and shaft are easy to seal and keep clean, and you can use rolling-element bearings rather than bushings between the two parts. Both changes make reduced friction likely in the TL’s damper, which has no exposed sliding surfaces. In contrast, conventional tubular shocks have a potentially dirty shaft sliding into and out of a seal, and such shocks are subject to bushing side loads. Both sources of friction increase the force needed to get the suspension moving.

However, rotary dampers still employ sliding seals to separate the working volumes inside the damper. Two rubber-tipped metal vanes mounted to the rotor seal against the inner diameter of the damping body, trapping damping fluid between themselves and another two vanes fixed to the damper body’s inner diameter. These vanes, in turn, must seal against the rotor’s outer surface. As oil is compressed by the two rotor vanes, it travels through ports to either the rebound or compression valve and washer stack. The damping orifices and valving work exactly the same way they do in a conventional shock. A small, pressurized gas chamber ahead of the rotor is only there to compensate for the thermal expansion of the oil as it heats up, as there is no rod volume to accommodate as on a telescopic damper.

It is in the sealing that a potential dark side of the rotary hydraulic damper lurks. Any leaks mean a loss of damping, just as they do in any hydraulic shock. All of the vane seals have to seal a rectangular area, and this is tougher than the annular area that a typical telescopic shock seal must cope with. Why? The rectangular area between the rotor and damper body has sharp corners that want to warp or bend, especially when the movement is in both directions. It is likely the assembly precision necessary to get the vanes to seal perfectly is what caused Suzuki and Kayaba to declare the damper non-serviceable.Since the sizes and volumes of the working chambers aren’t limited by the size of a coil spring’s inner diameter, the TL’s damper can pump a lot of oil. This high flow rate could be taken advantage of to make precise and fine damping adjustments easier than with the more-constrained tube shock design. In fact, the damping adjustment screws (compression on one side, rebound on the other) are quite easy to get at, with no remote mechanisms required.

As the damper is actuated by its own linkage, it can be set up for different rate rise than the spring. For instance, it would be possible to design the linkage so that the spring got stronger and the damper weaker as the suspension reached full bounce travel, or vice versa. This example is patently silly, but the separate linkage does offer unique (and potentially bewildering) tuning options if a serious tuner is willing and able to design and build new links.

Suzuki has given the TL’s damper a fairly flat-rate linkage so that damper strength stays fairly consistent with travel, while the spring has a progressive, or rising-rate design.

The biggest downside to the rotary damping concept might just be the total lack of a fall-back position. Think about it: If you don’t like the Kayaba or Showa shock in your traditionally-damped bike, you can choose from a number of alternative shocks from reputable aftermarket vendors. If you dislike the TL’s rotary unit, you’re up the creek without a damper — at least until the aftermarket starts producing shocks for the TL.

Suzuki has gone out on a limb with this design, but for some good reasons. We hope the limb turns out to be a strong one, for there are some clear advantages to the rotary design, and they help make Suzuki’s TL the stunning bike that it is.

Specifications, MPEGs, and Additional Photos:

Sport Twins #1: SuzukiTL1000S

View all VideosPHOTOS & VIDEOS

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

Tested the both, and loved them both but bought the VTR. It did lack top end power in comparison but was more comfy, and looked better put together. I kept it for 11 years, and touring on it ( yes, even with the 180km fuel range), ultimately led to carpet tunnel syndrome. I thought I would never have a bike that would wheelie like that again. But then I bought a 990 Superduke😁....

Most interesting ride I had on my superchicken was a loop around the Bay Area 280 around to SJ. A couple of CHP bikes waved me behind them and proceeded to stretch their legs. I didn’t know a VTR could actually go that fast until then...