MotoCzysz: The Story Of America's Ultimate Motorcycle

How a team of five took on the world

Recently, we brought you the story of Michael Czysz, designer/architect to the stars, fervent motorcycle enthusiast, and a visionary in the motorcycle world. It’s a tale of the man, his passion, his unfortunate illness, and how motorcycles make him feel alive again. Judging by the comments left by you, our readers, Michael Czysz has had an impact on many of you as well.

How did that come to be? In this, part two of the Michael Czysz story, we turn our attention away from the depressing topics of death and illness, and just talk bikes. We go back in time to chronicle how motorcycles and Czysz would eventually become so intertwined, the words combining to form a small company dedicated to producing America’s ultimate superbike in, of all places, Portland, Oregon. During our in-person interview, Czysz delves into what makes his bikes so special, and he puts forth his thoughts on the future – because he feels he’ll have a part in influencing it.

Humble Beginnings

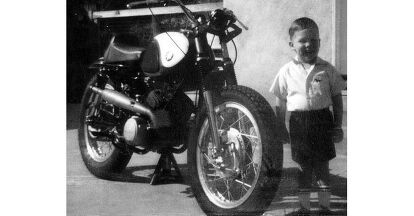

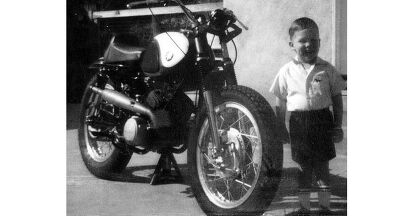

Like many riders, Michael Czysz’s life on two wheels started small. Around age four, a Sears minibike entered his life. Even at such a young age, Czysz’s eye toward design was present. “Aesthetically, I hated it even back then. I wanted a real tank, on top, and a real seat and a kick start,” he says. Despite its appearance, that minibike planted the seed for what would later become Michael’s second calling in life. “It was just backyard riding on that thing, but it was fun as shit, man!”

As he got older, by the ninth grade, Czysz saved up enough cash working summer jobs to buy his own motorcycle, a Kawasaki 175 enduro. Czysz remembers the headlight and license plate offered a certain sense of freedom. “With a motocross bike, you had to drive somewhere and ride around, then leave. And I wasn’t super happy with where I was growing up and the family environment I was in,” he says. “I just liked the idea of, ‘this is my adventure bike, and I can go anywhere in the world with it.’”

This is where the story takes an unexpected turn for a man now known to be inextricably tied to motorcycles. His two-wheeled connection ended, temporarily, after graduating high school. Czysz attended Portland State University, then left for New York and the Parsons School of Design. His design career was just getting off the ground, and what better place to do so than the bright lights of New York City.

However, the West Coast came calling again, and Czysz with girlfriend (now wife) Lisa made the move to Los Angeles. He was in his mid-20s, climbing the ladder in his field, when one day a chance spotting in the classifieds reignited his moto passion. “I was just flipping through the cycle trader and I found this old 1969 BMW R50/2 that looked cool as shit,” he says. “It just looked fantastically mechanical.”

Indeed, the flame was reignited. He bought the BMW and proceeded to quickly outgrow it. The self-described speed demon says the Beemer’s drum brakes, magneto headlight, low exhaust pipes and even lower centerstand were a severe mismatch for him. “I remember dragging the pipes on that bike, and the centerstand. I was hanging off, trying to get the bike to go faster and faster, but I couldn’t go any faster, that was it.”

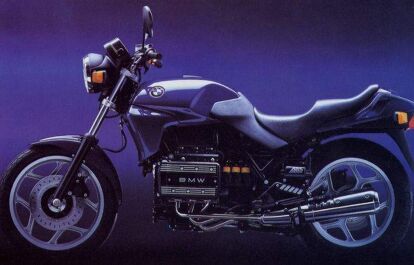

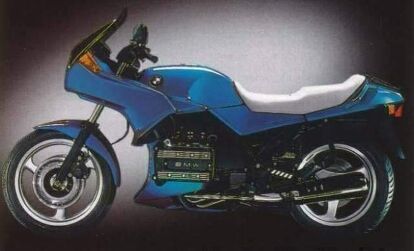

So, away it went, to be replaced with another BMW, this time the three-cylinder K75S. “That was a great bike,” Michael says, remembering the fond times he and Lisa had on it during their early years. “We put a lot of miles on that bike, my wife and I, and we really had zero money. A perfect weekend for us was just getting on the bike and going to some distant place. We’d spend the night in cheap hotels, get Chinese food, watch a movie, ride around somewhere, have a picnic lunch and come home. That was a killer weekend, cost us very little. And it felt incredible.”

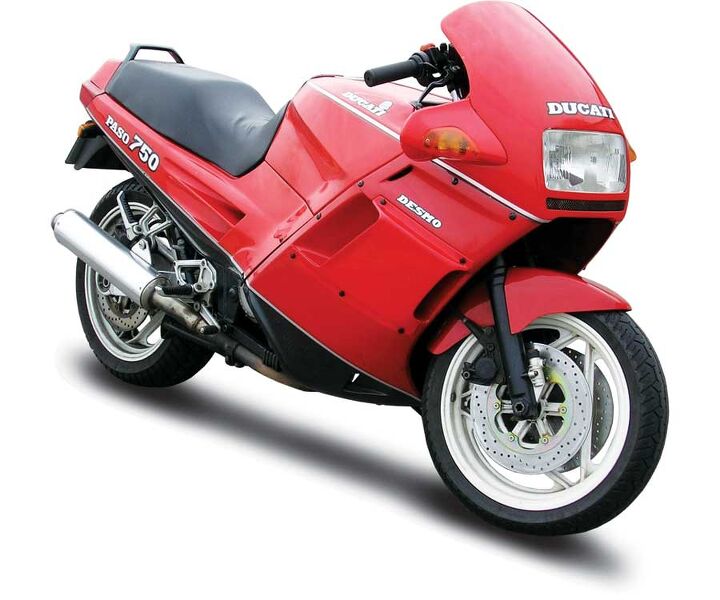

But the speed itch was one that needed to be scratched, and the K75, while a good tourer, wasn’t up to Czysz’s expanding performance needs. Up next: a (custom, by Czysz) Ducati Paso, the first of Michael’s Ducatis. While some might be completely satisfied getting the speed itch scratched by the Paso, it only served to deepen Michael’s desire to ride faster and corner lower. A desire spurred ever more by the introduction of the Suzuki GSX-R750 and Honda VFR750. “That changed everything,” he says. “I remember riding a GSX-R750 back then and thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is amazing!”

Enamored with performance, but remaining true towards his boyhood knack for aesthetics, it was a magazine review of the Aprilia RS250 that captivated Czysz next. Blown away by the sexy Italian lines, Czysz faced a harsh reality when he discovered the RS250 wasn’t sold in America. “I smuggled a couple in,” he grins. “I remember the first time I rode it, I felt like a racer. My dad knew some two-stroke tricks, and it was really awesome. But I thought I was going to kill myself, so I went to the track.”

Czysz was a fast learner, and at the age of 30, having never had any formal training, he participated in the Oregon Motorcycle Road Racing Association (OMRRA) new rider school. “I watched a lot and read a lot and was a quick study, I guess, but that day I went from never riding in the rain to doing stuff that felt amazing, to back to bottom. Clearly, I wasn’t that skillful.”

Maybe, but that experience clearly didn’t deter MC from coming back to the track. Still high from the buzz, he took the Aprilia and entered his first novice road race – and won. “If you want to get addicted to this sport, enter your first race and win it,” he says. From there the addiction continued. The RS250 eventually made way for an Aprilia AF1, purchased from the basement of a New York dealership with no idea what to do with it. “It didn’t even come with a manual,” Michael says. Without any direction on how to even start the bike, Czysz’s relationship with the AF1 was an uphill battle from the beginning, but it was one that eventually put him in touch with Giacomo Guidotti (with the help of Aprilia’s official race team).

Guidotti was an Aprilia czar working out of a shop in Italy. Today, he’s a crew chief on the Pramac Ducati MotoGP team. He eventually agreed to help Michael get his exotic AF1 working and flew over. Czysz chuckles as he says, “I’m pretty sure he did it out of pity.” Whatever the reason, the two characters quickly formed a bond that lasts to this day. In the meantime, Czysz took his “more” sorted AF1 to a class championship, after which the deal of a lifetime came his way.

“A friend of mine went to Italy and he called in the middle of the night and said ‘You know, Giacomo can build us two bikes, and if you want to buy one …’” Czysz then looks at me and says, “And that’s how I ended up with an ex-Max Biaggi Aprilia RSV250.”

Owning Biaggi’s old race bike would be a dream of many race fans, but Michael had no plans of displaying it in his living room. Instead, he fully intended to continue racing it. However, he quickly realized he’s not close to Biaggi’s height, weight or skill level. That’s when he looked for help. “I couldn’t ride the bike, I didn’t know what to do, and I wrote a letter to Freddie Spencer. I said, ‘I know you only do things with Hondas, but I’ve got this 250, I don’t know how to ride it, and I really need help. I could bring a few friends; could we hire you to do a mini-school for us?’ Just like Giacomo, Freddie took pity and said, ‘Yeah, I could help you out with your 250.’”

Like he did with Guidotti, Czysz hit it off with Spencer and that relationship, too, stayed strong throughout the years. Spencer is the only racer to win the 250cc and 500cc World Championships in the same year of the modern age, and he not only helped MC ride, but, more importantly, he helped Czysz understand what rider inputs do to motorcycles. “Which is now so obvious and almost second nature to me, but, frankly, that was the first time I had heard those words.”

Mid-Life Crisis

Czysz never did get along with the RSV250, but life’s other pursuits came calling, and Czysz had to answer. With kids now in the picture and his design/architecture firm, Architropolis, starting to grow, he simply didn’t have time for motorcycles anymore. “That was it,” he says. “No more street bikes and no more racing.”

In fact, Czysz spent the next decade of his life raising his two boys, while also elevating Architropolis to an elite status, designing Las Vegas casinos and taking on billion-dollar projects.

Suddenly, Michael was in his 40s, with a successful business, evaluating where he was in life. “I don’t know if it was a mid-life crisis,” he says, “but I just didn’t know if I wanted the second chapter of my life to be all about architecture carpet, wallpaper, and all those things. I felt like that was a meteoric rise and I hit some success, and maybe I should look into doing something more challenging.”

That’s when it hit him. “We consume more Ducatis and more Ferraris than any other country in the world, and we don’t make any of that. These guys in Italy and Japan are trying to figure out what’s good for the American motorcycling demographic? I’m that demographic. My friends are that demographic. I know that. I know what that is. It’s not lost in translation.”

Of course, the MotoCzysz story draws some parallels to John Britten and his famous attempts at taking on the world with his own motorcycle. This isn’t a coincidence. “I saw the Britten bike in real life, and that was my epiphany. I said there’s no way that this bike I’m looking at [Britten] is the last time somebody’s going to invent their own bike. There’s no way. Impossible. He’s not the last in history of motorcycling to make his own bike. So if that’s the given, which I accepted as the given, somebody else is going to do it. So I said, ‘F**k it , I’ll give it a shot.’”

Hence, MotoCzysz was born.

The goal was simple: to build the ultimate American superbike. Give it 200 horses, massive torque and the ability to transition faster. “I knew a couple of facts, and this is the God’s truth, now it’s proven to be the case: that bikes would rev higher in the future and that lean angles would increase. I said those two things are going to happen, what do we have to do?” The answer for Czysz was in the crankshaft design. More power for a given displacement required the crank to spin faster, but the gyroscopic effects would also affect handling.

“The two assumptions I made back then were about greater lean angles and more rpm,” Czysz says. “Those both work together and both of those pointed to the same thing, which was the crank, and one of them pointed to lateral suspension. So I said, okay, those will be my two disciplines I will try to master.”

Issues like these are challenges for even the brightest of engineers. Michael Czysz wasn’t an engineer. But like Czysz’s other pursuits, he proved to be a quick study. “I never had an architecture background either,” he says (he studied design). “You just encounter these problems and you deal with them, you learn along the way. I just had to figure it out as I went. I didn’t come from that field, but I wasn’t going to let it stop me from giving it a try. I stayed at the track and just looked at everything, absorbed everything, loved it all.”

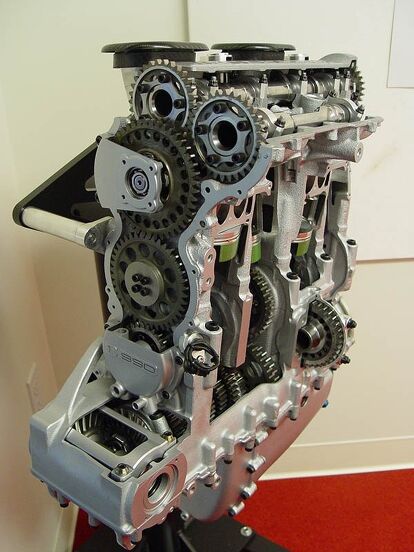

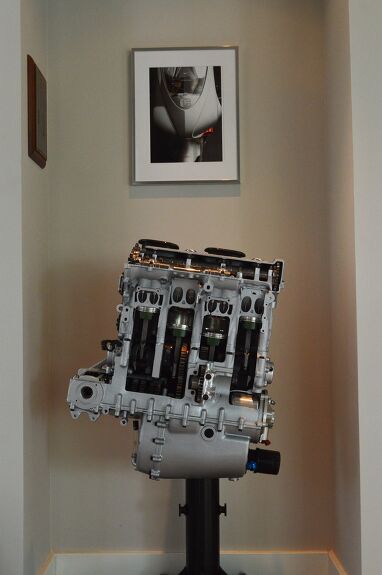

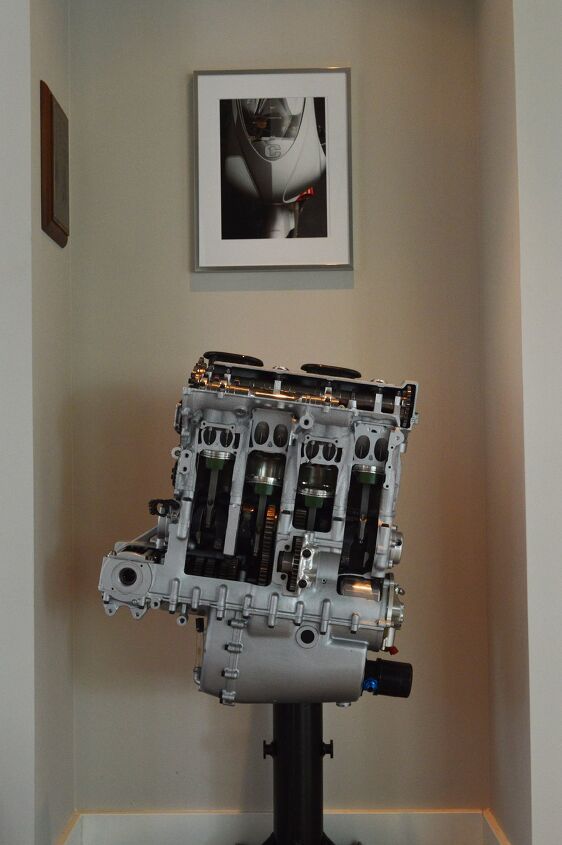

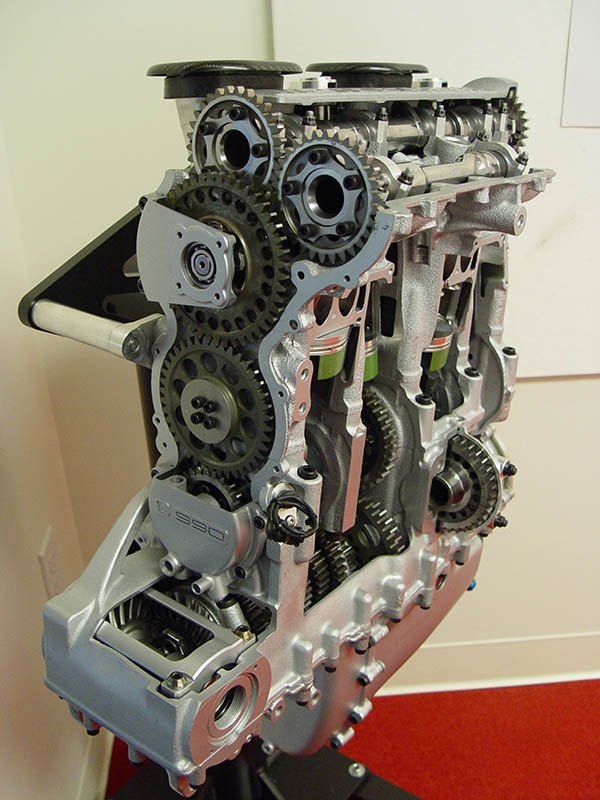

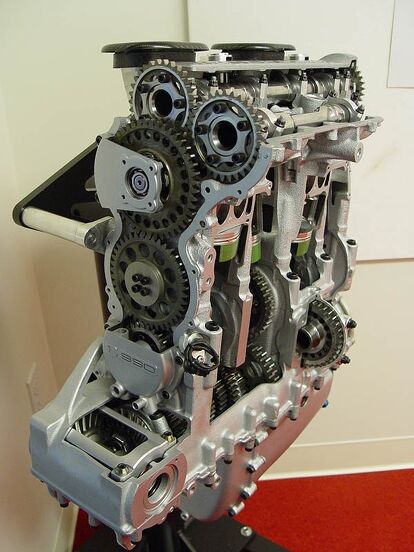

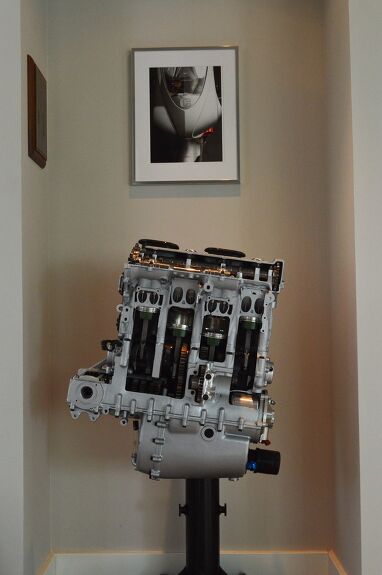

One thing he did know, even without an engineering background, was following the path of the established players, like Honda, was pointless. “We knew we wouldn’t hit the bullseye on day one – that’s not possible. But it didn’t make any sense to me to go through all this work and build a [transverse] inline-Four.” The four cylinder engine was the answer, of course, so it was decided to place it longitudinally. “I know it was a long shot, but that was the attraction.”

The advantages to a longitudinal Four were great. For starters, it allowed a narrow bike, only 6.5 inches wide – the same width as the rear tire. More importantly, according to Czysz, the bike could transition from side to side much easier since the gyroscopic forces of the crankshaft weren’t fighting the bike nearly as much. However, there were also some downsides.

The original design had the cylinders in line, and looked great on paper, but by the time you brought in the intake and put out the exhaust at reasonable angles, the engine was as wide as if we turned it around. So there goes that idea.”

Back at the drawing board, Czysz came up with an idea to design a narrow “V.” “I figured, why am I doing that when I could just offset the cylinders a little bit, then I could close those bores up. Then the intakes drop in better, the exhausts drop in better and it closes up significantly.” Czysz then made two peace signs with his fingers and then interlocked them, forming a W shape. “In fact, Volkswagen is using this now, too,” he says. “It’s called the W engine.”

A major benefit of the V15 (15-degree V) engine is the extremely compact dimensions you can achieve, but, according to Czysz, there are significant cooling advantages too. “By doing those cants, the bores can close up and you have a lot of cold water hitting the exhaust sides of the cylinders, and in fact we had virtually no plumbing on the bikes because I split the decks horizontally. The upper part of the cylinder is hotter than the lower part so we’d send in the water through the top level, and then use the lower level to return the water to the radiators.”

While Czysz and his team seemed to overcome the challenges of a longitudinal engine, anyone who has ever ridden a Moto Guzzi (fun fact: Czysz’s personal daily driver is a Guzzi V7), which also has a longitudinal engine, can attest to the torque effect when throttling the bike at a stop. While it adds character to a street bike, it hampers a racer’s ability to go fast. To counter this, Czysz split the crankshafts in two and formed contra-rotating cranks along the same axis, utilizing the first lesson we learned in high school Physics: for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. “We had a perfectly balanced engine and we didn’t have to counterbalance. That’s huge!”

The biggest unexpected advantage of this design was the sound. “It’s still the best sounding bike I’ve ever heard,” says Czysz. “It had a very American heavy kind of V-8 sound, but it just revved ridiculously fast, to 16,000 rpm.”

As history tells us, the C1 never turned a wheel in competitive anger. Blame the major sanctioning bodies. Originally, Czysz looked at World Superbike rules, which stated that small companies like his, producing a limited number of street bikes each year, only needed to homologate 150 bikes. “I thought I could sell 15 C1s,” he says. “That’s why the original prototype has a headlight.” But, of course, the rules changed.

Homologation numbers jumped to 1500 units for all manufacturers, “and I thought there was no way we were going to sell 1500 bikes the first year.” Czysz estimates he would have needed upwards of $20 million just to get the tooling needed to build that many bikes for homologation, so instead he looked across the way, to MotoGP and its field full of prototypes, which had recently switched to four-strokes. “I would have rather used that money, if we were fortunate enough to raise it, and go to MotoGP at that point. We could have gained more sponsors and then possibly reverse engineered a streetbike later on, similar to what Ducati did with the Desmosedici.”

In fact, it was relatively easy to configure a slightly smaller 990cc engine to fit MotoGP requirements. But just as the C1 was coming to life, the death knell for the C1 project rang: MotoGP was switching to 800cc engines. “The 800s changed everything,” Michael says. “They revved to 18,000 rpm. That’s pneumatic [valve] territory, and we just couldn’t afford to develop them. Not to mention you can’t use pneumatics on the street.” With funds practically dried up on a bike that was suddenly obsolete, no interest in developing two concurrent technologies (pneumatic for the track, conventional valves for the street), nor the ability to homologate 1500 bikes for WSBK, “It felt like we had nowhere to go.”

Electric Rebirth

As the saying goes, when one door closes, another one opens, and that’s the situation Czysz found himself in. “I heard the first murmuring of electric bikes, and honestly, I had zero attraction to it. Then, when he thought about the future, he realized, “I can try to catch up in a 100 year-old industry and be the last guy to the dance, or I can jump over and be maybe the leader in this new area.”

So, he jumped in headfirst, and knowing there wasn’t much he could do about trimming battery weight, the main singular focus was breakneck acceleration. What Czysz wanted was torque numbers similar to second gear on a motorcycle, but from 0 to 180 mpg, in a single gear. “That’s what was lost on most,” he says. “Our bike may have developed 250 lbs.-ft. of torque, but that’s nothing with a one-to-one ratio. That’s like sixth-gear acceleration on a ICE bike. If you take a [Ducati] Panigale and do the multiplications through the transmission, and the gear reduction of the rear, you’re going to find that it has somewhere around 600-850 lb-ft of torque. So, day one, I wanted that.”

Czysz hit that mark, but to maintain that torque for any period of time the batteries needed to be mighty impressive. “With our partner Dow Kokam, MotoCzysz made some very impressive energy dense battery packs. What made them so amazing was that we didn’t have to sell them to consumers,” he says. “They were also stressed – not from a safety standpoint, but we could pack a lot of energy into a small space and were monitoring up to 40 different thermal allocations. We’d run them almost to the point of thermal meltdown because that’s how you got the most out of them. You just can’t do that on a street bike.” By the end of MotoCzysz’s run, in 2013, just four years after entering his first bike in the TT Zero races, the E1pc batteries were pumping out over 400 volts, 400 amps and over 16.5kWh of energy.

The early models used modified C1 frames, featuring “hot swap” battery technology. From there Czysz moved to a new carbon fiber chassis designed specifically for his electric grand prix machine. The proprietary liquid-cooled, permanent-magnet brushless motors were tucked underneath the batteries or, on later models, integrated into the subframe. At their max, Czysz claims 250 lbs.-ft. of torque and more than 200 hp.

Then, of course, there were the four Isle of Man TT Zero victories – the entire reason for the E1pc’s existence in the first place. Admittedly, the first year “was a complete joke,” Czysz says, since there wasn’t much competition and the bikes were slow. The second year showed signs of legitimacy, but the third year was when things started to get interesting.

“Third year, we brought our third new bike, and Michael Rutter did a 99.8 mph average, crossing the line at 120 mph. He scared the shit out of people who had never seen an electric bike go that fast! He came flying by so fast we thought the throttle was stuck wide open. It was unbelievable. The TT Zero race went from being a joke to something interesting in three years. This was really the birth of the electric ‘super bike.’”

It was the third and fourth years, 2012 and 2013, where a real rivalry started to develop. Enter Mugen, backed by the mighty hand of Honda. Despite showing up with 20 guys, two trick bikes and John McGuiness at the helm, Czysz won again. “It was beautiful,” Czysz says. “All of a sudden, this [TT Zero] is the most technically advanced bikes at the IoM. Both Mugen and MotoCzysz were scrapping our bikes every year and coming back with ground breaking technology. And we were just a team of five people. That’s just unbelieveable.”

The Future

Unfortunately, the fairytale story that is MotoCzysz doesn’t end with a bang, but is, instead, a firecracker with a cut fuse. The Mugen vs. MotoCzysz battle was forming into the stuff of legend, but Michael’s unfortunate cancer diagnosis prematurely and suddenly curtailed the rivalry.

Through it all, however, Czysz had no ambitions of building any electric motorcycles for the street. His eyes were on a much bigger prize: transforming the two-wheeled landscape as we know it. His vision? A hybrid. “Everything that I’ve learned will lead up to this,” he says. “There aren’t a lot of people that have designed a complete internal combustion engine and a complete electric motor. I’ve designed both. Now it’s about bringing those together. A hybrid is the next great thing to happen in motorcycling.”

At this point Michael switches gears, being extra calculated with what what he reveals. He assures me this isn’t a hybrid in the traditional sense. A gas engine and electric motor aren’t fighting for space underneath a motorcycle frame. “It is truly part of internal combustion and part of electric, it’s a totally new architecture.” Any technical details beyond that, however, and Czysz is staying tight-lipped.

“I’ve got a deal. It’s done. Signed, inked, done.” Czysz is excited about the opportunity, stating that, despite his hatred of electrics for a street bike, “there are still aspects of electric that are undeniably awesome.” Combine the character and passion of a gas engine with the efficiency and torque from an electric motor, and Czysz predicts a vehicle that can transform motorcycling.

Czysz says, “Somebody is going to have to go out there, create the hybrid and show them [riders, racers, OEMs] it’s better. I so want to do that, I’m so ready. I’m going to be so disappointed if I don’t get that shot.” And in case you’re envisioning Prius-like excitement levels on two wheels, Czysz says his hybrid design doesn’t alienate his fellow speed demons. “Just look at Formula 1,” he says. “Those are the most technically advanced cars in the world, and it’s basically a hybrid series now.”

Despite Czysz becoming closely guarded with his words, he seems so convinced his hybrid technology is the wave of the future. You almost get caught up in the moment. Though part of the reason for his keeping secrets close to heart is the fact he hasn’t filed any patents. Citing his health and the money involved to even file a patent, “’I’m tired of raising money, and I’m tired of making sales pitches, that’s just not what I want to do anymore.” However, according to Czysz, hybrid specialists from Mercedes-Benz have already vetted his idea and confirmed it can work with today’s technology. “So, let’s get going.”

In my conversation with Czysz, I got the impression he still wasn’t satisfied with the legacy he would leave behind. Never satisfied, if he’s right about hybrid design in motorcycles, Michael Czysz won’t have to worry about his legacy anymore.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

Just awesome.

Finally an answer as to why they bounced, thanks, good read.