The Brains Behind Brembo

Ducati’s new 1199 Panigale, ( which we reviewed here) is being heralded as one of the most technologically advanced sportbikes ever produced. From its monocoque chassis that uses the engine as the frame, to the engine itself, which claims one of the largest bores in production V-Twin history, almost everything about the Panigale is cutting edge — including its brakes.

Ducati worked extensively with Brembo in creating the braking system seen on the 1199, including its bespoke M50 monobloc (one-piece) calipers biting on 330mm discs. Leading the way for Brembo was Chief R&D engineer Roberto Lavezzi. A modest Italian and owner of many patents, we had the chance to speak with him at length regarding his and Brembo’s involvement not only with the 1199, but also in shaping the world of braking technology as we know it.

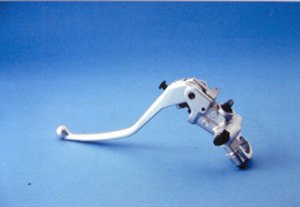

One of Lavezzi’s first patents was the radial-pump master cylinder. “This is a fun story,” he tells us. “In 1984 we [Brembo] got the patent for it and first used it in [Grand Prix] racing the same year with Eddie Lawson.” Which, as we know, is the year Lawson won the first of his four world championships.

Interestingly, Lavezzi says Brembo had issues fitting the radial master cylinder into production motorcycles of the time. Tight packaging created interference issues. Radial master cylinders didn’t make it into production until the 2003 edition of Aprilia’s RSV1000 Mille, which also featured the first use of radial-mount calipers that Brembo initially developed for the Aprilia RSW 250 two-stroke GP machine of 1997.

Another fun fact: the radial master cylinder is a “mirror project,” Lavezzi says. Both the brake and clutch master cylinders come from the same mold. The difference is in the machining to accommodate the various piston sizes for clutch or brake applications.

But back to Ducati. Italy’s most iconic brand proved to be a tough challenge for Lavezzi as all he knew was this new M50 caliper was to be responsible for stopping Bologna’s next flagship motorcycle. There was one clear design goal in mind: supreme weight savings. In October 2009, Lavezzi and his team met with Ducati brass and proposed an answer — make everything smaller.

“The only reasonable and cost effective solution was shrinking the size of the parts,” Lavezzi says. This rather unusual and unconventional answer didn’t sit well with Ducati because “they believed bigger was better.”

“The truth is that if you reduce the size of caliper pistons, then the master cylinder piston must be reduced as well” Lavezzi says. “That way, you increase the working pressure but the forces remain the same.”

After two months of deliberation Ducati agreed and development of the M50 caliper seen on the 1199 Panigale commenced. The end result is a caliper 7.5% lighter than its predecessor thanks to pistons that shrink in size to 30mm from 34mm and a smaller size of the calipers themselves.

The calipers shrunk in size with help from “topology optimization” programs that allow engineers to remove excess material without compromising overall integrity. As Editor Duke attests to from his experience on the Panigale, there’s no shortage of braking power despite the reduced size of the components.

This is achieved by using the same friction materials as before. “We reduced the length of the caliper from 171mm to 143mm, but the pads and friction dimensions are still the same as previous,” Lavezzi says, adding, “reduced piston size also means smaller holes in the caliper body, making it more rigid.” A benefit he says you can feel at the lever.

When Ed-in-Chief Kevin Duke tested the Panigale at the fantastic Yas Marina Circuit in Abu Dhabi, he had nothing but praise for the new Brembo system. “The petite clampers deliver a perfect blend of power and sensitivity,” he wrote. “Lots of feedback encourages trail-braking to corner apexes.”

The future of the M50 caliper is unknown at this point, as it’s a “very race-oriented caliper,” says Lavezzi, but it’s almost certain to be seen again on other Ducati models. Whatever Ducati decides, it has sole use of the caliper for one model year, as is customary when a manufacturer enters into an exclusive partnership with Brembo. Other manufacturers will have access to the M50 beginning model-year 2013, so we won’t be surprised to see them on Aprilia’s next RSV4.

These days, braking systems are not the only part of Lavezzi’s duties. He also oversaw the development of the 1199 Panigale’s wheels. Again, the goal was weight savings, but making them attractive and functional was also very important. The end result was a wheel with three spokes branching from the hub, each separating into three smaller spokes at the rim.

“More contact points between spokes and rim mean there are less concentration of stresses,” Lavezzi explains. “Previously there were seven contact points [on the 1198 wheels], now there are nine. Reducing the stresses allows you to reduce the weight of the part.” This adds up to a 1-lb weight reduction compared to the already-light forged wheels on last year’s 1198SP.

Lavezzi could speak for hours about his work with Brembo, from his time leading the racing department to the many patents he holds “that aren’t just written on paper, but are real things that are in production today.”

From his knowledge of friction materials to his experience working with numerous manufacturers and race teams — both in the motorcycle and automotive fields — Lavezzi is a walking encyclopedia and history book of how far stopping a vehicle has come and will likely have an influence on where it heads in the future. “I still like my job, so it is a pleasure to speak about these things,” he says.

Related Reading

2012 Ducati 1199 Panigale Review

Brembo Announces Suzuki Partnership

Brembo Updates Radial Master Cylinder

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation