Metzeler’s 30th Anniversary of the 0-Degree Steel-belted Radials

Three decades of refinement

Tires, oftentimes, are the unsung heroes of the motorcycling world. We use ’em – sometimes abuse ’em – and then toss ’em in the gutter and go buy another. When you consider the demanding burden that these black hoops are expected to manage, and now, more than ever, multitask, it’s an arduous assignment that rarely gets its due. It’s easy to forget the amount of time and money dumped into R&D to make tires what they are today.

Recently, I had the privilege to visit the Metzeler tire factory located in the Odenwaldkreis district of Hesse, nestled in the midst of lush countryside and rolling green hills in the town of Breuberg. Since the late 1970’s, the 160-year old company has been producing motorcycle tires in this facility. More than 300 different tires are manufactured in this location and, increasingly, without a human hand touching them, but more on that later.

Metzeler invited myself and three other fortunate ones from around the world for a peek behind the blue curtain to celebrate 30 years of its 0-degree steel belt technology. The late ’80s blasting through into the early ’90s were a golden age of motorcycling, I’m told. I was barely a twinkle in my father’s eye. Manufacturers were producing motorcycles that were pushing the performance envelope in a way that hadn’t been seen before, and that meant everyone else had to step up, too – including tire manufacturers.

Previously being involved in the manufacture of giant balloons and sausage casings, Metzeler was by that time purely focused on motorcycle tires, and the common bias-belted or cross-ply tire construction had, until this point, been absolutely adequate. Metzeler made tires for racetrack use, which handled those duties with aplomb, and likewise made touring tires that did just fine when gobbling up miles. The problem was that it was basically one or the other and nothing in between. To make things worse, once those tires began to reach the end of their lifespan, they had lost so much rubber, 1.5 to 2 kilos in some cases, that the damping effect the compound provided was essentially gone, making them very sensitive to disturbances on the roadway and, consequently, quite unstable. The level of the machines coming out around this time only exacerbated the issue.

Reducing the sidewall height allowed for the switch to radials, but many of the same problems persisted. Michelin was the first to try a 0-degree radial, which was a departure from the standard 90-degree radials that handled well while cornering, thanks to their ability to handle side forces, whereas with a 0-degree Kevlar construction, the side force resistance was no longer there. Straight line stability was gained, and resistance to road imperfections increased with this new construction, but at the detriment of cornering performance. At this time, the original problem still persisted.

Current Executive Vice President of Research and Development and Cyber, Pierangelo Misani and Head of Global Testing and Technical Relation, Salvatore Pennisi began considering what was missing from the motorcycle tires. Looking to the automotive sector, and likely inward as Pirelli had purchased Metzeler at this point, “They have crossed belts, we have crossed belts, they have steel, we don’t have steel,” thought Piero. At the time however, this was an easily dismissed idea. Nobody could see the benefit in using steel in motorcycle tires according to Piero.

Misani wasn’t convinced. Automotive used steel for its compression resistance. “Why wouldn’t it work in a 0-degree radial to increase cornering stability,” he thought? Metzeler hoped to find the balance that they hadn’t achieved before, and what they found with the 0-degree steel belt construction is that they had achieved just that – not only the straight line stability, but the tire now had the compression resistance to hold up to cornering forces. The stability was there even in worn out conditions. Then, at 45 degrees of lean angle, the same tire’s characteristics changed entirely. “For us this was the key of the steel,” explained Piero, “Basically you have Dr. Jekyll on the straights, quiet and respectable, but in the corners, you have the crazy guy, Mr. Hyde.” Metzeler had finally achieved its goal, but there was still a prototyping period that they had to work through to have achieved this.

At the end of 1992, everything looked good on paper, but they needed to prove the concept. Salvo Pennisi, “It was a fantastic experience because all of the activities that we were carrying out before with the other tires and older technology, but now on new, extremely powerful motorcycles, you definitely felt like you were living life on the edge because the bikes were very dangerous.”

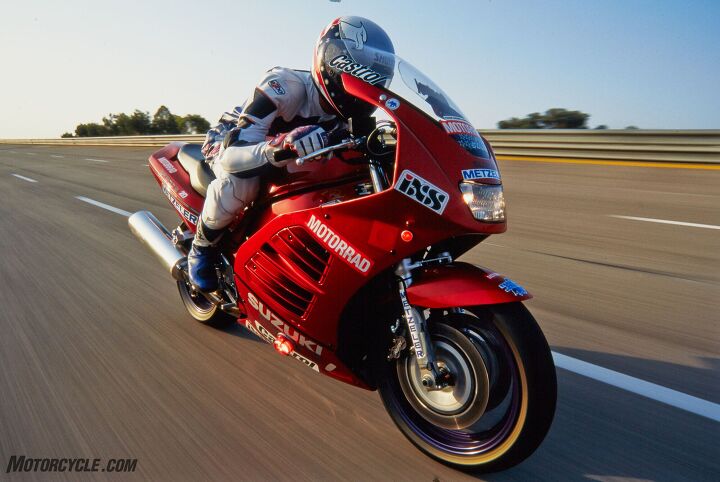

“I cannot forget the first time that Piero gave me the first prototype of the 0-degree steel belt,” explains Salvo. “I can also not forget,” shouted Piero! “I was really astonished,” Salvo continues, “I cannot forget. I was riding a Suzuki GSXR750 and, I shouldn’t say, but I tested this bike on the motorway at quite a fast pace, and this bike with our radial tire was really astonishing in terms of handling, in terms of sporty use and so on, but on the motorway it was a little bit… nervous, we will say.”

Salvo starts to gush, “The first prototype of the 0-degree steel belt was incredible.” “No, no, no. Don’t say only the good things, be honest, tell the truth,” interjected Piero. “It looks easy, we put some steel inside and the situation is solved.” said Piero “Just one problem,” says Salvo as Piero recounts his memory of the situation, “I remember the test on the motorway. Salvo called me after the test, ‘I went out on the motorway full throttle, max speed,’ which we would never be allowed to do today, mind you, ‘and started shaking the bike myself, but the bike was always stable. Fantastico!’ He just kept going on so I said, Salvo, now tell me, but… where is the but? ‘But, when I have to turn, I have to stop, put the bike on the side stand, turn the bike, and then start again’ He’s always been a little bit exaggerated, but that was to say that we got the result in the straight line stability, but with the steel we were still missing the full speed response while leaning. That’s why we decided that we needed to completely redesign the tire.”

Back to the drawing board. Metzeler ended up totally redesigning the tire from the contour and shape, to the profile and compound. It was important to ensure that the compound worked well with the tread design to handle the cornering forces. Metzeler made the new compound harder than before but didn’t lose any of its grip.

“The hardness is the capability to envelope the road surface,” explains Salvo, “The stiffness is part of the construction. So we had to develop tires that were stiffer, but not too hard to compromise grip. We had to redesign the character of the tread compound. The ME Z1 was the first tire where we truly got both kinds of performance.”

Metzeler used championship racers from all over to test the tires, including Davide Tardozzi, Adrien Morillas, Walter Villa, and Helmut Dähne. The problem with the original prototype was the compound. They couldn’t get more than five or so laps out of the tires. Piero recounts one particular test with Walter Villa, “I remember getting a call while Walter was testing, ‘I have to tell you,’ said Walter, ‘the compound was okay, but the grip of the steel is not good. After five laps I was running on the steel. It was not very comfortable for me, but in the night for the spectators, fantastic. Plenty of sparks everywhere.’ Five laps and the tire was done.”

Clearly, Metzeler needed to turn its focus to longevity. In 1994, the ME Z2 prototype was created with a new compound. In an effort to prove the endurance of the ME Z2 and the Suzuki RF 900 R, Metzeler, Suzuki Deutschland, and German magazine Motorrad teamed up for a handful of world record attempts. The 30-person crew came away with six world records, perhaps the most impressive, the new 24 hour record: 5900.426 km with an average speed of 152.764 km/h.

Metzeler had achieved its goal, and four years later the first set of 0-degree steel belted radial tires were available to the motorcycling public. Up until this point, Metzeler were only manufacturing rear tires with this technology. In 2002, the company patented its Metzeler Advanced Winding (MAW) technology, which optimized the spacing between the steel belts to give the tire specific handling characteristics. Six years later the company realized that it could alter not only the spacing, but the tension of the steel cord. With the steel belting being a cord, meaning that it’s made up of 12 pieces of steel twisted together, the company used what it calls “high elongation” to embed certain characteristics into the tire. This process allows for varying levels of stiffness in different areas of the tire again, to achieve the desired performance.

Think of the belt and tread as two springs in a row. If you make one spring stiffer, the second one will have to work harder to absorb the deformation. You want this to warm up the tire, but you don’t want this to wear the tire. Tire manufacturers can use this variation to warm up the tire more on the edge, and vice versa, to not to wear too much in the middle. So, this interaction of the two “springs”, the tread and steel, allows for another level of fine tuning that works together in different areas of the tire.

This level of refinement is key to developing tires that work in a vast range of scenarios. Of course in order to reach these technological advances, the manufacturing process needs to constantly be advancing, too. Currently, 25 year old machines work with actual humans at various steps of the process while, across the room, fenced off robotic arms contort and fling tires high into the air like pizza dough at other steps of the process. The goal is to have the entire process done by robots, and Metzeler plans to have the switch done sooner than later. Working with the robots thus far has brought quality control to an inhuman level and allowed the R&D process to speed up exponentially.

I’m told Metzeler will have a brand new 0-degree concept for us next year that focuses on ultimate performance, while allowing the company to move toward a more sustainable future. If the past 30 years of innovation have proven anything, I can’t wait to see what’s next.

Become a Motorcycle.com insider. Get the latest motorcycle news first by subscribing to our newsletter here.

Ryan’s time in the motorcycle industry has revolved around sales and marketing prior to landing a gig at Motorcycle.com. An avid motorcyclist, interested in all shapes, sizes, and colors of motorized two-wheeled vehicles, Ryan brings a young, passionate enthusiasm to the digital pages of MO.

More by Ryan Adams

Comments

Join the conversation

The 1994 RF900R maintained an average speed of 153mph? I didn't think it could even go that fast!

That bike could have been the new 900 Ninja (in spirit) if it wasn't so lame looking.

Oh boy ! I wanna see hot tires getting tossed in the air like pizza pies by giant transformer like robots. I really want to see this !