The Amazing History of Supercharged Motorcycles: And What the Future Holds

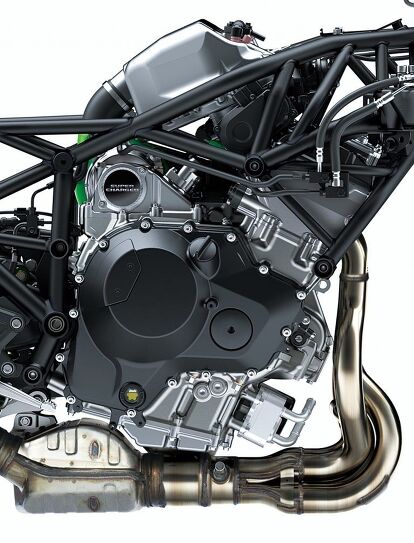

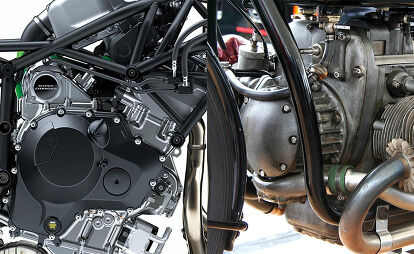

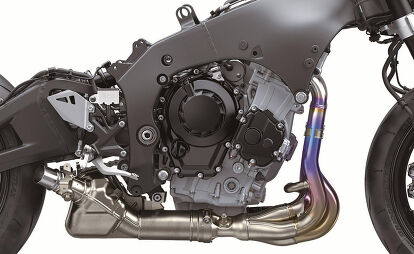

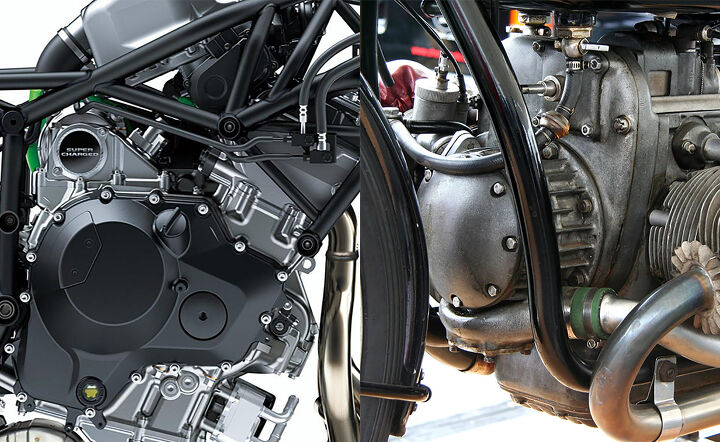

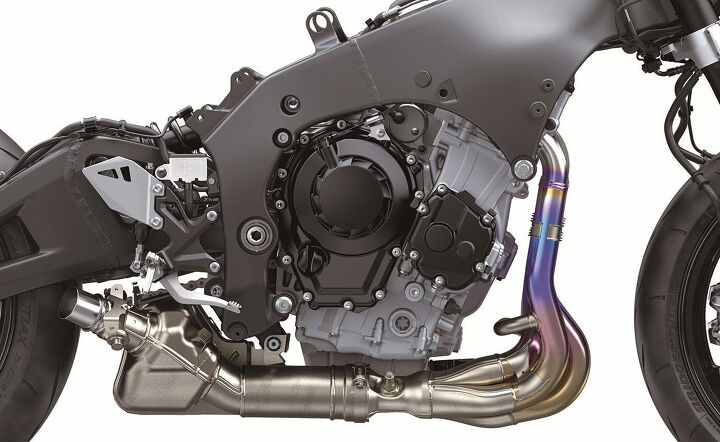

Who’s the most exciting motorcycle manufacturer in the world? It’s Kawasaki, and I wasn’t really aware of the fact until they loaned us a few supercharged motorcycles: an H2 SX SE a couple of years ago, followed up lately by an H2 Carbon sportbike, and now an Z H2 naked bike. What they all have in common is Kawi’s excellent supercharged 998 cc inline Four – an engine that made over 200 rear-wheel horsepower in the H2 Carbon without really even breaking a sweat: 205.5 hp @ 11,600 rpm. It helps that all the Rivermark-branded systems surrounding those engines are top-notch as well.

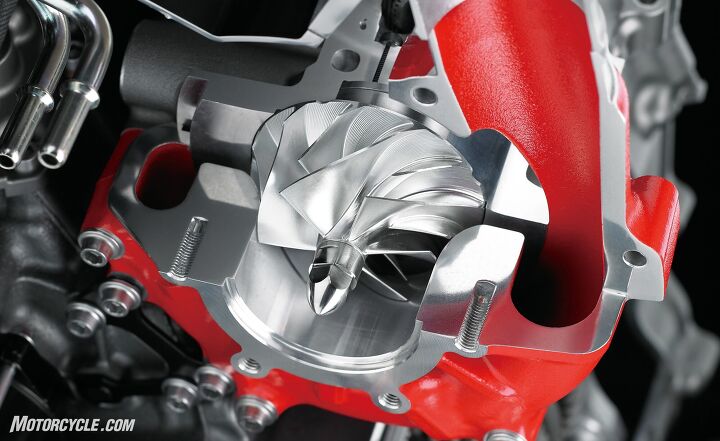

But let’s face it. The H2s are all expensive motorcycles; the Z naked H2 is the cheapest of them, at $17,500. It probably wasn’t inexpensive to develop that supercharger. After they tried to farm the job out to the specialists and were told it couldn’t be done without a bulky intercooler, Kawasaki took things in-house and seem to have succeeded spectacularly. If history is any indication, these blown Kawasakis will be just as hard to kill as everything else the Japanese megalith builds, including the earlier GPz750 Turbo, which is to say very.

BLOWHARDS! 1984 Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo Vs. 2020 Kawasaki H2 Carbon Vs. Ken Vreeke And JB

Why’d they do it? Because they’re Kawasaki, and have a history of blowing up the status quo with irresponsible motorcycles. But in the 21st century, there are other forces at work also – legal ones that require ever-constricting combustion cleanliness, for which supercharged engines are particularly well-suited.

If you follow cars at all, you’re already aware that those manufacturers have been getting lower emissions and better fuel mileage through the use of turbo and superchargers for a while. Even stuffed with extra fuel and air, smaller displacement engines still produce fewer noxious emissions than bigger ones. Heck, Volvo’s latest T6 Polestar engine uses a turbocharger and a supercharger to produce 362 horsepower, from just two liters. Which is good in car terms, but not as good as the H2’s 200+ horses from one liter.

More rpm equals more problems…

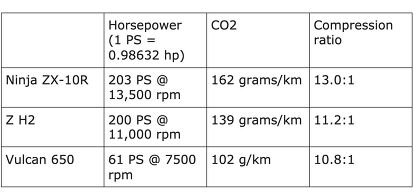

Motorcycle engines’ biggest emissions hurdle – especially high-revving ones – is in the hydrocarbons department, HC, where the requirement has dropped from 0.170 grams/kilometer under Euro 4, to 0.100 g/km under the new Euro 5 regs. Hydrocarbons are unburnt fuel, quite a bit of which escapes due to the kind of long valve overlap high-revving things like Kawasaki ZX-10Rs require in order to make 168 horsepower at 11,800 rpm (the last time we dyno’d one, in 2017). Alas, keeping up with the World Superbike Joneses hasn’t made life any easier: Kawi’s UK site says the new, 2021 ZX-10R makes max power at 13,500 rpm.

Making power at really high rpm means exhaust valves have to open early and close late to let all the gas out, which is great for power but not for emissions. Likewise intake valves; all that overlap, when both intake and exhausts are open at the same time, lets more fuel blow through without being burned.

2018 Kawasaki H2 SX SE First Ride Review

Reviewing Kawasaki’s H2 SX SE a couple years ago (whose sport-touring tuned blown H2 only made a measly 172 horses to the H2 Carbon’s 205), we wrote:

There are more powerful 1000cc sportbikes than the ZX-10, including the 180-hp Aprilia RSV4RR and 177-hp BMW S1000RR that duked it out in last year’s Superbike Shootout. But they make their power well past 13,000 rpm; you have to work for it a little. The H2’s artificial air inseminator lets its 998cc four-cylinder produce its peak at just 10,300 rpm. And even more to the point is the fact that the H2’s blown motor is making more torque way sooner – 89 pound-feet of the stuff at just 8600 rpm. The S1000RR puts out 80 lb-ft at 9600 rpm, the Aprilia 78 lb-ft at 11,300.

Getting the same power with less rpm is a win/win situation for rider and environment. An H2 feels like it’s always rolling downhill ahead of a strong tailwind; the torque’s the thing most of the time on the street. And our 2018 H2 SX SE recorded 40 mpg, too – anywhere from 2 to 8 mpg better than the 2017 superbikes from that last big comparison.

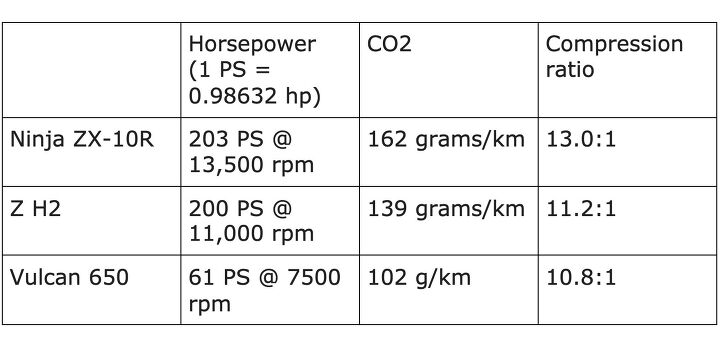

Carbon Dioxide

Strangely enough, one of the nasty byproducts of combustion Euro 5 does not address is CO2, good old carbon dioxide. Maybe that’s because CO2 isn’t poisonous like the others? But, and it’s a big but, CO2 is the gas an increasing number of countries are basing their increasingly popular carbon taxes upon. On most European websites, “grams/kilometer of CO2” is now a spec in the chart along with “bore x stroke” and the rest of them, to allow dealers and customers to anticipate their bottom line.

Here’s a sampling of them from Kawasaki’s UK website:

As far as the noxious gases Euro 5 actually does control, the Z H2 continues to outperform, matching the ZX-10R’s 1.0 g/km of HC and NOX, and spitting out even less deadly CO – 1.23 g to the ZX-10R’s 1.457 (and again comparing favorably to the Vulcan 650’s 1.118 g/km of CO).

Meanwhile at MV Agusta…

We turned to our friend Brian Gillen, R&D Director of MV Agusta for enlightenment:

Please note that HC, CO and NOx emissions requirements are ever-tightening and that during the WMTC (world motorcycle test cycle) emissions test, a lower geometric compression ratio with reduced squish can help reduce the NOx generation. Having a turbo/supercharger then allows you to recover the compression ratio by force, over-filling the cylinder and upping the effective compression ratio, and allowing you to reach the desired performance targets. At the same time, you can have very low overlap valve timing which helps eliminate the short-circuiting of fresh fuel/air directly from the intake tract to the exhaust, thus reducing HC emissions. It’s a win-win.

Given all the benefits of supercharging, why did we stop doing it anyway? Mostly because when racing restarted in 1946 after WW2, the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) banned forced induction from road racing. It was a way to keep both costs and fatalities down. And until very recently on the historic timeline, nobody gave a damn about cleaning up exhaust emissions. Lots of people still don’t.

Before the war, everybody was supercharging engines, from BMW to Brough Superior to DKW and right across the board, in a crazy era when tires and chassis and fairings were learning how to deal with 160 mph plus speeds the hard way.

Mostly, motorcycles have been fast enough for most of us this last half century without the added complexity and expense of super- or turbocharging. The hands-on accessibility of bikes has always been a big part of the charm until not long ago. But now, as manufacturers begin coming up with more complex strategies like variable valve timing, in an attempt to meet Euro 5 and beyond (our man Dennis Chung wrote an excellent coping-with-Euro 5 article here two years ago), supercharging begins to look relatively simple – especially with the new electronic controls that didn’t exist when all the Japanese OEMs tried their hand at turbocharging in the early 1980s.

The Copenhagen Connection

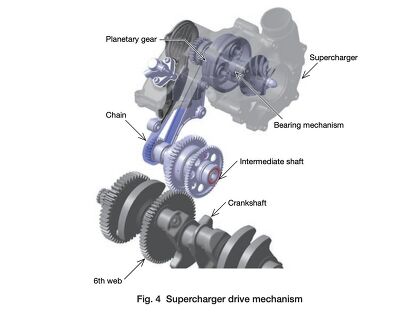

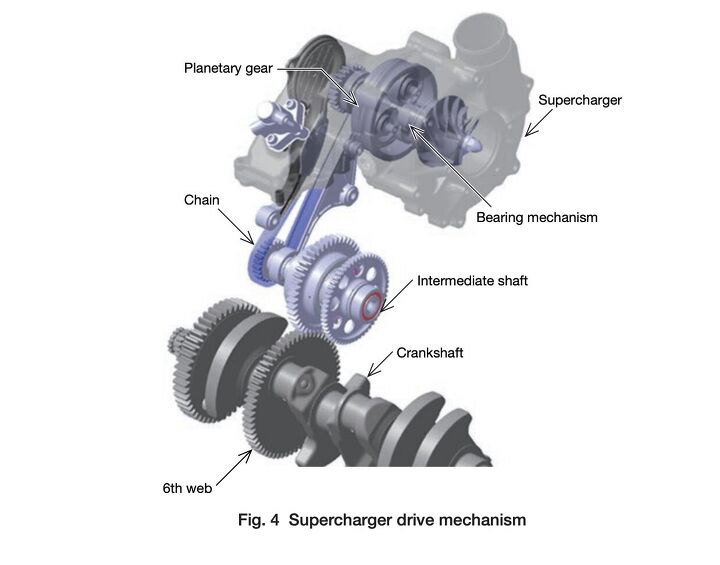

Kawasaki deserves full credit for its revolutionary 2015 H2R and the later street versions of that beast, but its very cool planetary drive supercharger may not have been quite as groundbreaking as we were led to believe. Since the 1970s, a little-known company in Copenhagen (meaning, I didn’t know about it until Brian Gillen mentioned it) called Rotrex has been in the business of speed, and had its first supercharger drive patented in 1996.

Similar to Kawasaki’s unit, Rotrex’s advanced “traction drive” system is able to greatly step up impeller speed from engine speed, achieving impeller speeds way above 100,000 rpm. And like Kawasaki’s supercharger, Rotrex does it without the aid of an intercooler, which makes it easy to package on a motorcycle. It’s all about the “adiabatic efficiency,” according to this article in Hot Rod from 2005.

Adiabatic efficiency describes an air compressor’s ability to compress air without increasing air-charge temperature. The higher the efficiency, the lower the intake-charge temperature and the higher the density of the compressed air-cooler… In a perfect world, a compressor would be 100 percent adiabatic efficient, but in the real world, adiabatic efficiencies range from a low of about 40-50 percent for a Roots-type supercharger to slightly above 80 percent for the most efficient turbochargers. A typical centrifugal supercharger is about 60-65 percent efficient, but according to Rotrex, the higher impeller speeds its units generate elevate them into turbocharger efficiency ranges of up to 80 percent or higher.

How hard would it be to put one of these on a motorcycle? Not very, apparently, since Rotrex has been selling kits for a bunch of bikes for years – including Harley’s new Milwaukee 8s (and now defunct V-Rod). But Rotrex’s bread and butter is definitely automotive; kits for the Camaro SS on its site claim to take that 6.2-liter Chevy V-eight from 455 to 610 or 750+ horsepower.

Interesting, isn’t it? All our man at Kawasaki is allowed to say is,“Kawasaki is always looking at the market and developing new product for our consumers. While we cannot comment on future models, our Supercharged family of motorcycles has been a huge hit in the market and we continue to look at this technology and future applications.”

I think that means that after they went to all the expense to develop that supercharger tech, they’d be fools not to use it going forward. Lots of the magazines are full of conjecture about the possibility of a new supercharged Eliminator like the old ZL1000. And why not, since Kawasaki has now already built a naked H2, a few sporty ones, and the SX SE sport-tourer (my favorite).

Where do we go from here?

Personally, I’d be more excited to see Kawasaki supercharge a midsize bike to give it liter-bike power. A 135-horsepower ZX-6R wouldn’t be a bad thing, but an 80-hp Versys 650 ADV bike with about 70 lb-ft of torque, a low seat, and a cruise control button would be even better for me most days.

After explaining to me the advantages of supercharging and calling it a win-win, Brain Gillen at MV Agusta closed with, “yes, we’ve been working on a project at MV for some time now!” and closed with a winking smiley emoji. All but one of MV’s models are powered by its excellent 798 cc Triple, with current horsepower claims ranging from 110 to 153 hp. Add 40% to those numbers for a general idea.

Who knows, but sometimes life has a way of reasserting why old sayings like “it’s always darkest before the dawn” still apply (though it may be time to throw out “there’s no replacement for displacement”). Weirdly, nearly all the Euro 5 bikes I’ve ridden run better in stock form than the Euro 4 versions did, but the screws are only going to tighten further going forward regarding exhaust emissions. And can we please bypass, in the Comments section, whether that makes sense or not? Governments gotta govern.

The naysayers were certain emissions controls were going to bankrupt Detroit in 1970, when the US Congress passed the first Clean Air Act, which required a 90 percent reduction in emissions from new automobiles by 1975. There were definitely some dark years while the engineers figured it out (and while you could buy late-model muscle cars for like 5% of what they go for now unless you were a penniless youth), but current Detroit products will bury any Hemi Cuda, stock for stock, without asphyxiating following traffic or requiring toxic, leaded fuel.

All to say, if you’re saddened by electric motorcycles, and already mourning the demise of internal combustion, you might be a little early to the funeral; a whole renaissance of highly advanced, yet 1930s-simple supercharged motorcycles might shortly be upon us.

Related reading:

Kawasaki Development of Supercharged Motorcycle Engines

Turbocharging, Supercharging To Help In Engine Downsizing, Emissions Compliance

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

Aw, JB, dig into the MO minefields, including this Rotrex-equipped machine: https://www.motorcycle.com/...

https://www.motorcycle.com/...

And my fave: https://www.motorcycle.com/...

Very nice, John. Good mix of looking back and looking ahead. I'd love to think forced induction offers hope for the future, but pretty soon we're going to have to stop burning fossil fuel. (That's a simple technical/chemical observation, not a political position.) Maybe there's a window for Kawasaki's supercharging efforts to help for a while. Longer term, we should all be rooting for Porsche's efforts to master synthetic fuels, which would keep internal-combustion engines alive without extracting crude or fouling the air.