Lightning: Building Electric Motorcycles

Turning ideas into motorcycles

For whatever reason, American motorcyclists have been very slow to adopt electric motorcycles, ironic since the most innovative and interesting e-motos are built here in the USA. Zero and Harley-Davidson are both in the electric motorcycle game, and two start-ups – Brammo and Alta Motors – delivered hundreds of motorcycles to paying customers before succumbing to tough market realities.

So, it was surprising to see a third San Francisco Bay Area-based company toss its helmet into the mainstream ring, announcing plans to produce a motorcycle with more range, higher top speed, better components, and a faster recharge time than Zero and Harley-Davidson… at a price comparable to gas-powered middleweight sportbikes. And it’s a company that’s produced a relative trickle of production motorcycles since its founding in 2006.

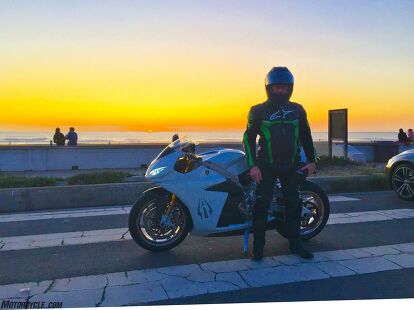

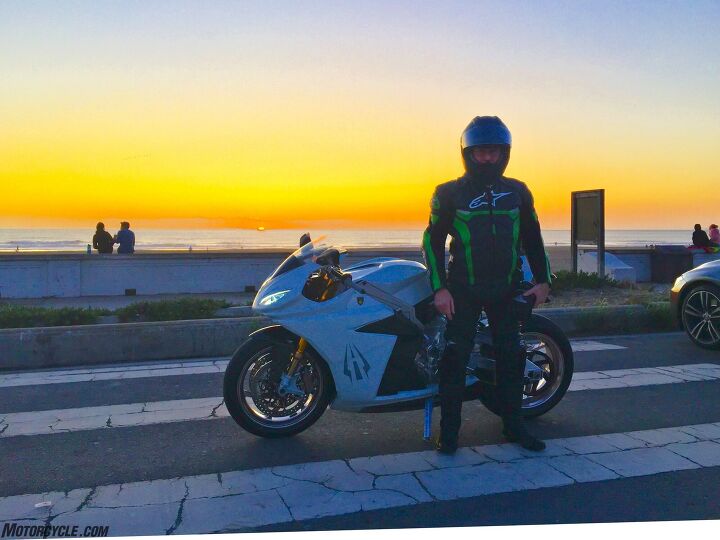

That company is San Jose, California-based Lighting Motorcycles. Founder and CEO Richard Hatfield hit the world with the Strike, a 150-mph, fully faired sportbike that can go as far as 180 miles on a single charge, can recharge to 80% off a DC fast charger in as little as 45 minutes, and all for a starting MSRP of $12,888 for the 130-mph, shorter-range base model.

A pipe dream, no? Ain’t no way one of these bikes will see a customer’s garage! $12,888 is $689 less than a 2020 Yamaha R6, a bike with similar performance. It’ll be years before that’s possible.

Except it’s apparently possible now. On September 8th, 2019, a guy named Kevin Barnard swung a leg over production Strike number One and rode it home. Had it happened before I had a chance to see the factory and meet Hatfield, I would have swallowed my chewing gum in surprise. Lightning is an interesting company, helmed by an interesting guy, but it’s had a long history of doing more racing and getting in the motorcycle press than of building large numbers of bikes.

Back in 2012, our own Troy Siahaan rode Hatfield’s prototype LS-218 race bike, and Lightning was taking orders for street-legal models. We don’t know when the first orders for the $38,800-superbike were placed, but we do know the first one wasn’t delivered until November 2014. It wasn’t until May, 2017 that San Jose tech worker Guido Seibt picked up his frame number 29. Lightning says the usual time between ordering and delivery is about a year, but is “working on reducing the delivery time on the LS-218 to 90 days.”

So, when Lightning teased us with firm info on that lower-priced, 150-mph sportbike (that Hatfield’s been promising since before he launched the LS-218), I was openly skeptical that any production machines would leave the factory. San Jose is just a 45-minute ride from where I live in Oakland. So, I decided to check things out for myself.

Richard was waiting for me when I pulled up. He’s a low-key, soft-spoken guy who’s already had a successful career in the intersection of finance and tech. After talking about my personal bike (an FZ-07), we headed into his 20,000 square-foot facility in San Jose’s low density Santa Teresa neighborhood. Entering the slightly grungy, lightly cluttered space, you get the feeling it’s a cross between a hands-on machine shop and a slick Silicon Valley startup. The general ambiance doesn’t shout “poseur!” in the way some other startups I’ve examined do: there are motorcycle people here.

Electric motorcycles are scattered about, including Lightning’s GM-motored Pike’s Peak racer and land-speed-record-setting LS-218, along with a small fleet of Chinese-market small-displacement sportbikes that are used as test mules for Lightning batteries and powertrains. There are also Strikes in abundance – not just the display prototypes, but production bikes in various stages of assembly.

I also saw an area devoted to making carbon-fiber parts, a well-equipped machine shop, cubicles for engineering and software teams, 3-D printers, and a table of scaled-down parts to help figure out assembly processes and other issues (“where do you find the 1/4-scale test riders?” I asked Hatfield. Without missing a beat, he replied “we print them too”). In other words, Lightning’s facility in San Jose is a small but complete factory capable of turning out “a lot more” than the five or six bikes per week I thought he could build, all at a price way lower than Zero or Harley Davidson could dream of.

How? Lightning has a secret weapon: China. Thanks in part to its energetic COO, the Chinese-speaking JoJo Hatfield. Partnered with what Lightning describes as the largest manufacturer of electric scooters and bikes in Southern China, the factory can crank out the thousands of precision parts the Strikes will need, at the competitive prices volume manufacturing yields.

Quality of Chinese-made parts can be much higher than the chintzy $4.99 gimcracks you’ll find on Amazon: pull the phone out of your pocket, a phone that’s probably been working for months or years with no problems, and you’ll know what I mean. And your Japanese, German or even Italian motorcycle likely has some Chinese-made parts, parts that you don’t know about because they don’t ever fail. My own FZ-07 is probably mostly Chinese, though you’d never know by looking at it. Lightning’s quality assurance is done in San Jose via a battery of closed-circuit monitors showing stages of the parts-production process.

Once delivered, the parts are assembled into motorcycles in San Jose. That gives Lightning even more QA control. I’ve seen plenty of assembly lines, and though Lightning’s isn’t the best-organized or most-modern I’ve seen, I’m reasonably certain that it’s a real assembly line capable of producing large numbers of bikes. It’s certainly enough capacity to satisfy demand for bargain-priced 150-mph electric sportbikes.

Guido loves his LS-218. An experienced rider – his other bikes are a 2006 BMW K1200S and a KTM dirt bike – he put 5,000 miles on his LS-218 before an errant car sent his bike back to Lightning for crash repair. With 200 horsepower and 168 lb-ft of torque, it’s not a beginner’s ride. “It requires lots of getting used to: the first five miles, I did three wheelies.” Of course he loves it: “There’s no clutch, no shifting, you ride with just the throttle…you can focus more on the road and where you’re going.”

Ownership of a Lightning has been surprisingly seamless for such a low-volume, high-performance ride. Aside from the crash, the only issue Guido had was an electronic component that failed in the rain. Living a few miles from your motorcycle’s factory has its benefits: He called Richard, who came to the rescue 45 minutes later with a truck.

This time, after #29’s wounds are healed, it will also get a new 23 kWh battery and 10 kW DC fast charger. This will bump Guido’s range to as high as 180 miles, and cut charge time to about an hour. Hatfield says the battery upgrade will cost about $8,000. If that price seems high (are you proud of me for not writing “shockingly high?”), consider some dudes spend double that getting a 20 or 30-percent horsepower boost. The bike’s weight should be about the same; that’s the miracle of advancing battery and charger technology.

The Lightning factory and HQ isn’t an overwhelming experience: it’s a place where real motorcycles are designed, assembled and delivered. So, I was soon back at the front door, wrapping up my interview… and then Richard asked if I wanted to take a Strike test mule for a short ride. Of course I did, so he wheeled it out for me, showed me how to switch it on, and sent me on a mile-long test loop around the factory, advising me that the bike I was riding wasn’t the production model and had different tuning and other differences.

This is by no means a full road test, or even a real “first impression” sort of review, but what struck me about the Strike wasn’t its tech. Sure, it felt like an electric motorcycle, with smooth acceleration and seamless response, but it also felt old-school in its ergonomics, weight distribution and handling. Hatfield’s first e-moto was a first-gen Yamaha YZF R-1 conversion, and that DNA was apparent in the Strike’s deliberate steering and solid, carved-from-billet feel. Richard told me the Strike’s battery box sits high on the frame, where the fuel tank would be on an ICE moto, to give the bike stability in high-speed turns. It’s ironic that the future of sportbikes – designed in the USA, built from parts all over the world, dependent on 21st-century technology – has such a classic look and feel.

Lightning won’t reveal how many bikes it has built or how many it plans to produce annually. When I asked why, Hatfield cited “business reasons. Numerous business reasons.” When I asked him how many Strikes he wanted to build, he told me, “We think this can be a 10,000-plus a year bike. Our goal is to make them available to everybody in the world who wants one.” Unlike the LS-218, which Hatfield described as a technological “showpiece” available in 2014, when no previous production electric bike was as fast or capable.

Building low-volume, hand-built custom machines is not what he wants Lighting to be. To achieve his goals, he’s thinking big. “Do you want to be Britten or Honda? Koenigsegg or Toyota?” We’re not going to reach an electric-vehicle future without mass-produced, affordable electric motorcycles that can compete in almost every way with gas-powered models: think Tesla on two wheels.

That Tesla comparison is apt, as more than one journalist and electric-motorcycle enthusiast expressed concerns to me (not on the record) about Lightning overpromising and under-delivering, with doubts about getting product in a reasonable time. Hatfield told me that the long delay bringing the production LS-218 to market were to be expected: “We’re not a huge team and we had to learn how to develop bikes we could be proud of. Even large companies take time: Harley-Davidson is in its 10th year with the Livewire.” That Hatfield and a few engineers took less than two years to make a bike compliant with dozens of regulatory agencies all over the world seems remarkable to me, as I have a hard time filing my taxes within six months of April 15th.

Critics would point out that other companies don’t take deposits (or require prepayment) until they’re more certain of a delivery timeline, but one customer I talked to – Guido – plunked down his $500 deposit and patiently waited almost two years and is glad he did. Hatfield told me the average wait for an LS-218 is more like a year. And in the case of the Strike, if Kevin Bernard took delivery in September, less than six months after ordering opened in March.

I’m looking forward to testing more Lightnings, and I know I’ll ride them in the future. That’s because though Lightning lacks the slick PR, experienced product development and polished hipster image some other 21st-century manufacturers sport, it does have the facilities, resources, designs and tech know-how to make it happen. All it needs is customers: maybe one is reading these words right now.

Gabe Ets-Hokin has a range of 12 miles and a top speed of 7 mph. He can recharge to 75% in 10 hours on a level-1 charger if he falls asleep binge-watching “Stranger Things.” Buyers will receive a conditional $7,500 tax credit if they take delivery of one before December 31, 2019.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

Does anyone plan to buy an electric motorcycle in the next couple months?

I heard Zero hired Greta Thunberg as its spokesman. She's going to visit Zero dealerships around the country and berate customers looking at IC motorcycles.

I love this! The comments section can be more entertaining and informative than the great read from Mr. Ets-Hokin. Great use of vocabulary and language ensues here, learning about those who read and comment. Opinions and facts intertwined. I have experience on a number of brands, types, small, large, light and heavy. Rebuilt many neglected bikes that saw tens of thousands of miles under my scrawny frame. But electric, no experience, so I can only speak to my feelings that if given the opportunity, I'd gladly embrace it. Will I live long enough to be able to do so and see it accepted by the majority? That's the unknown, which I embrace also.