Vincent Series C Black Lightning: History on Wheels

Next month, at the U.K.'s Classic MotorCycle Show, Bonhams is auctioning one of the rarest, most iconic motorcycles of all time, a Vincent Black Lightning. The last Black Lightning to hit the auction block sold for US$929,000 in Jan. 2018. Alan Cathcart had the luxury of testing a Vincent Black Lightning, so it makes sense for him to explain just why it has gained a mythical status among vintage motorcycle enthusiasts.

The auction will be held April 20-21, in Stafford, UK. You can learn more about the Black Lightning and all the other rare motorcycles up for auction here. —Ed.

The ultimate Vincent was the Series C Black Lightning, a customer version of the bike on which Rollie Free had broken the AMA’s Land Speed Record in 1948 on the Bonneville Salt Flats, with a similar engine specification. First exhibited at that year’s Earls Court Show in London, and available only to special order, the standard Black Lightning was supplied in racing trim, with rev counter, Elektron magnesium alloy brake plates, special racing tires on aluminum rims, rearset footrests and controls, a solo seat, and aluminum mudguards. This reduced the stripped-out Black Lightning's dry weight to 360 lbs against the road-going Black Shadow’s 458 lbs, complete with lights and a horn. Its 998cc air-cooled high-camshaft dry sump OHV 50° V-twin engine measuring 84 x 90 mm and fitted with two valves per cylinder was upgraded with higher-performance racing components, including Mark II Vincent cams with a higher lift and more overlap, stronger highly polished 85-ton Vibrac conrods with a large-diameter caged roller-bearing big end, polished flywheels, and Specialoid pistons delivering a high 13:1 compression for methanol fuel.

The Black Lightning engine’s spherical combustion chambers were both polished, as were the valve rockers and streamlined larger inlet ports blended to special adapters, and fed by twin 32 mm Amal 10TT9 carbs. A manual-advance magnesium-bodied Lucas KVF-TT magneto ran 34° advance as standard ignition timing, with two inch-diameter straight-through thin-gauge exhaust pipes. The Ferodo single-plate clutch’s cover featured center and rear cooling holes, while the four-speed gearbox was beefed-up to transmit the extra power, amounting to at least 70 bhp at 5,600 rpm (compared to a road-going Black Shadow’s 55 bhp at the same revs), and a proven top speed in competition guise of 150 mph, and upwards.

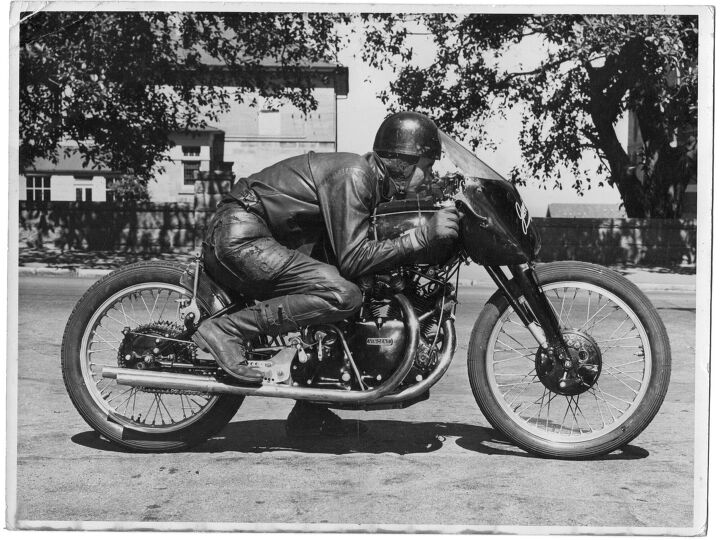

The Black Lightning’s genesis is the stuff of legend for Vincent enthusiasts, which essentially began with London Vincent dealer Jack Surtees, the father of future World champion and Vincent factory apprentice, John. He’d been racing a Norton sidecar outfit with some success, and in 1947 ordered a Rapide from Vincent’s Stevenage factory fitted with some special tuning parts. This engine was built alongside a second such motor, which was then loaned to the firm’s Experimental Tester since 1934, George Brown, who gave the ensuing bike its competition debut at Cadwell Park in Easter 1947. For the Unlimited capacity Hutchinson 100 race at Dunholme later that year, Brown’s special Rapide was further improved, allowing him to finish second in the race to Ted Frend’s works 500cc AJS Porcupine – a bike that would win the inaugural 500GP World Championship in 1949. However, unlike the AJS, the Vincent could be fitted with silencers for Brown to ride it the 120 miles back to the factory after the race!

This specification was largely adopted on Vincent’s new production Black Shadow – the uprated version of the Rapide that famously needed a special 150 mph Smith’s speedo instead of the standard 120 mph item. The engine of the new model, at first produced in very limited numbers, was stove-enamelled black, and to assist with publicity, Brown’s bike likewise had its motor painted black, with Brown continuing to race the machine to successive British hillclimb, sprint and short circuit victories, including a 1949 win in the Unlimited capacity class at the first motorcycle race meeting to be held on the new Silverstone circuit.

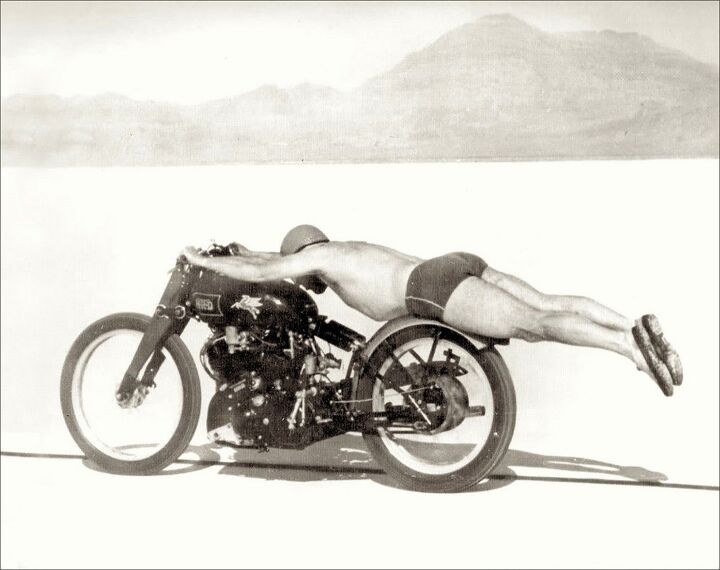

Phillip Vincent then agreed to sell a specially-prepared Black Shadow to wealthy Californian enthusiast John Edgar – the machine to be ridden by Rollie Free at the Bonneville Salt Flats in an attempt on the AMA’s Open class Unstreamlined Speed Record, then held by Harley-Davidson. To meet the September 1948 date for the attempt, much midnight oil was burnt at the factory to produce the necessary go-faster bits, and Edgar’s engine was run-in on the test-bed before being installed in a Black Shadow chassis and tested at Gransden airfield. With Brown aboard, it ran easily to 143 mph and would have gone faster had the runway been long enough. In Utah, Free, famously clothed in just a pair of swimming trunks and with his legs stuck out behind him, smashed the AMA record on the Vincent, leaving it at 150.313 mph (241.905 km/h) over the flying mile.

The idea of producing a special racing model based on Free’s record-breaker was a logical progression in what was to be a very big 12 months for the Vincent HRD company. London’s Earls Court Show, which had not been held since 1938 owing to the outbreak of war, was revived in November 1948, to tremendous support from British manufacturers.

The completed Black Lightning caused a sensation at Earls Court, despite its enormous £400 price tag (plus a hefty £108 purchase tax) – then sufficient to purchase a nice three-bedroom family house in London. It’s widely accepted that only 30 complete customer versions – all Series C except for one Series D model – in addition to Rollie Free’s first 1948 Series B prototype were ever built (together with anything up to 13 engines for installation in racing cars, usually with a Cooper chassis), before production ended in 1952 because of Vincent's financial problems.

Today, nineteen of these bikes are believed to still exist, so the astronomical values achieved at auction on the rare occasions when one comes up for sale make the Vincent Black Lightning the most coveted production motorcycle ever made. That status was confirmed by the January 2018 sale at the Bonhams Auction in Las Vegas of the completely original/unrestored ex-Jack Ehret Australian land speed record breaking Black Lightning, which was only retired from competitive racing in 1993, having also won the Australian TT at Bathurst, as well as numerous other races Down Under in its 40-year track career. This bike went under the hammer for USD $929,000 incl. buyer’s premium, making it still today the most valuable motorcycle ever sold at a public auction.

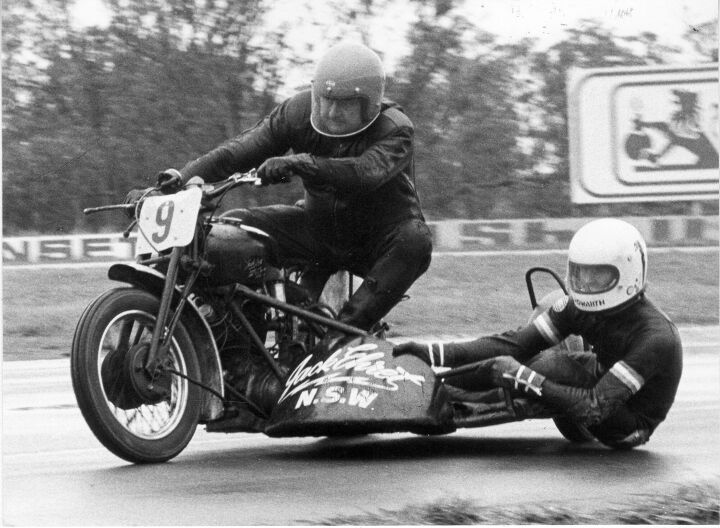

This makes the forthcoming appearance in the Bonhams sale to be staged at the UK’s 2024 Classic MotorCycle Show at Stafford on April 20-21, of one of the so-called ‘Polish Black Lightnings’ particularly significant, albeit as essentially a barn find that has remained in a fortunately dry garden shed ever since 2000, when it was restored for its late owner – who then never rode it, and seemingly rarely even looked at it! This bike carrying engine no. F10AB/1C/3230 in frame no. RC5130C was the 14th Black Lightning to be constructed after the model’s debut in November 1948, and is one of a pair of such bikes despatched to Poland one year later. Factory records show its companion machine was delivered on November 15, 1949, and this its sister bike followed exactly two weeks later, on November 30. Both motorcycles were specifically ordered as being intended for Sidecar racing.

This was at a time when Poland had sadly once again lost its independence in the aftermath of WW2, becoming a Communist satellite state in the USSR-controlled Eastern Bloc. In such Marxist societies the ruling authorities controlled almost every aspect of their population’s daily life, and as such private citizens were not allowed to import any goods at all from outside the Eastern Bloc for their own consumption – much less complete motorcycles, and especially not such a costly device as a Vincent Black Lightning! Accordingly, the two Vincents were ordered directly from the British factory by a Polish government agency, the CHPM/Centrala Handlowa Przemyslu Motoryzacyjnego Motozbyt (aka Commercial Headquarters of the Automotive Industry’s Motorcycle Division). This meant that both the 13th and this the 14th production Black Lightnings constructed were evidently destined for influential Communist Party insiders who knew how to pull the necessary strings.

The Vincent Works Order Form shows that this machine was delivered without lights or a horn, and besides the standard Lightning spec carried a 280km/h speedometer, straight-through exhausts, racing alloy mudguards, larger 52T and 56T rear sprockets suitable for sidecar use, steel rims, touring footrests, wide ‘bars and sidecar mounting brackets and suspension springs. But both bikes were supplied in solo form, so the sidecars themselves would have been added on in Poland. Vincent factory records show that, upon completion, this Black Lightning was tested by 'CJW', believed to be its Works Manager Jack Williams, later to be the creator of the Matchless G50, and father of Peter of Arter Matchless and John Player Norton fame.

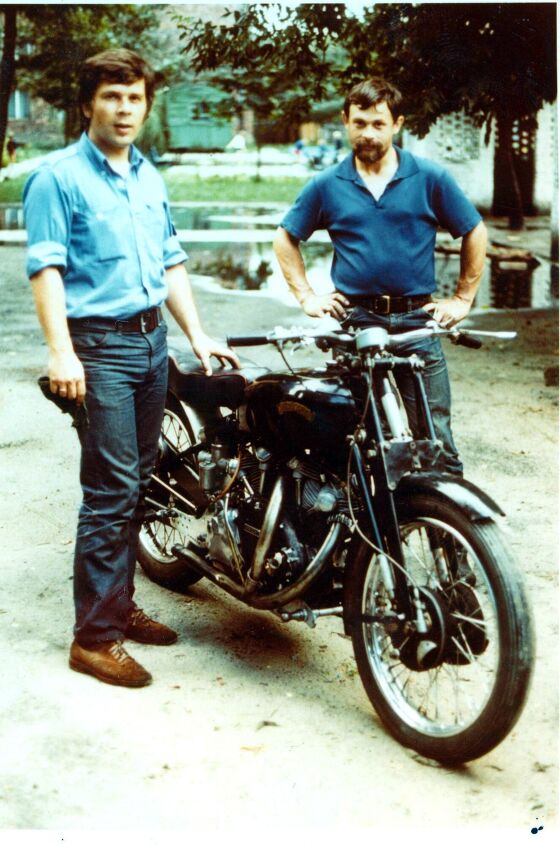

A decade later in 1971, with Poland still very much under Communist rule, British Vincent Owners' Club member Ian Harper decided to visit the country on his 'Green Meanie' Vincent Rapide special. While in Warsaw, Ian met up with two Harley-Davidson riding brothers, Andrzej and Woyciech Echilczuk, who told him that they knew of a Vincent somewhere in the city. This turned out to be one of the two mythical 'Polish Lightnings' that Vincent aficionados knew to have ended up on the other side of the Iron Curtain, but had given up for lost. Just over a year later the brothers had tracked down the second such bike, both of which Harper managed to extract from Poland on two separate trips to bring the Black Lightnings back to the UK. No.13, the second bike to leave Poland (but the first of the two to be shipped there in 1949) is now in the UK’s National Motorcycle Museum – but this other version, no.14, has lain undiscovered for the past quarter-century.

For, once back in the UK, Ian Harper did little to the two Polish Lightnings before selling both of them on in 1973 to George Brown’s successor as the Vincent factory’s tester/racer Ted Davis, later its Chief Development Engineer. This motorcycle’s late owner – who must remain anonymous under auction sale protocols – duly acquired this Black Lightning from Ted Davis in 1976, and eventually commissioned marque specialist Bob Culver to restore it, a task completed in 2000. But thereafter, instead of being used or displayed, the Black Lightning was placed under a pile of blankets in a fortunately dry garden shed, where it has remained for the last 24 years. Presented in what Bonhams describes as 'barn find' condition, the fully restored time warp machine will require at the very least recommissioning, before returning to the road.

If and when that happens, I’m fortunate to be one of the very few people on Earth to know what the lucky future owner has in store, because back in 2016 I was honored to be given the chance by its French then owner Nicolas Dourassoff to track test the ex-Jack Ehret 1951 Vincent Black Lightning for two dozen laps of the Carole race circuit on the outskirts of Paris. This motorcycle was living history on two wheels, with just 8,682 kilometres from new on its 300 km/h Smiths clock, almost every one of them in anger. But the battle-scarred warrior had been recommissioned by the late French Vincent expert Patrick Godet for me to ride on a sunny afternoon Parisian track day. However, so that I could properly sample how a Black Lightning should perform without paying due deference to the bike’s age, Godet also brought along a recently built 100% authentic Black Lightning Replica which he’d created for another of his customers, Englishman Peter Fox. Peter had already covered 1200 street miles on it, pronouncing it “huge fun, and incredibly impressive once you get it revving, when it feels like you’re being pulled along by a huge bungee cord!”

Thanks, Peter – I couldn’t put it better myself, for that was indeed the impression I got on the Ehret Vincent once I saw its Smiths Chronometric rev-counter’s needle track its way with traditionally jerkiness to the 3,800 rpm mark, whereupon the bungee cord released and I was swept to what must have been unthought-of speed by mid-20th century standards. Nothing much happened below those revs, though, so I had to coax the engine into meaningful action with a dab on the Ferodo clutch’s light-action lever. But from that access point to its inbuilt grunt onwards, the paragon of performance that all this Black Lightning’s records and race victories proclaimed it to be, made itself apparent. In no time at all the rev counter was showing the 6,000 rpm mark, at which point I stabbed the extended gear lever downwards with my right foot to hit a higher ratio of the four available. There were such massive amounts of torque even by today’s standards that the Vincent just lunged forward in the next higher gear when I got back on the throttle again, noting as I did so that its action seemed unaccountably smooth, considering how worn the self-evidently ancient cables sprouting from the right handlebar and leading to the twin Amal 10TT9 carbs, appear to be.

That’s because, in recommissioning this retro-racer for track action in accordance with Nicolas Dourassoff’s belief that historic bikes should be seen and heard in action, not stuck in a garage on permanent static display, Patrick Godet had been at pains not to destroy the truth of time. “Once Nicolas decided to preserve the bike in its current state, and not ask me to restore it – which was 1,000% the right decision – I wanted to make sure that all the new parts I fitted were as least obvious as possible,” he said. “So we stripped the bike totally, and rebuilt it using the original spec parts we’ve manufactured using Vincent’s original Black Lightning drawings that we’ve obtained. We’ve also converted it to running on petrol rather than methanol, since of course we now have much better fuel available today than they did back then.”

The same thing applied for the original 20-inch rear wheel which had been replaced by a 19-incher, on the grounds that 20-inch racing tires are no longer available. Now shod with rear Avon GP rubber matched to a front 21-inch ribbed Avon Racing cover, the Ehret Vincent tracked well through Carole’s mickey-mouse infield section, with good grip delivered exiting either of its pair of hairpin bends, which on most racebikes ask for bottom gear. Not on the Black Lightnings, though, thanks to their huge reserves of torque and the way they broke into a gallop very quickly in second gear once I’d straightened up. I just had to finger the clutch lever lightly to send the surprisingly responsive engine’s revs soaring to the sound of thunder from the straight exhausts, whose stirring hard-edged note denoted heaps of valve overlap.

When that happened I found myself thundering past the R6 Yamahas and 600 Hondas that had out-manoeuvred me in the infield section, only to let them fly past me once again when I anchored up miles earlier for the next hairpin – just as they were probably about to hit top gear! The brakes on the Vincent were easily the worst thing about riding it, and I needed heaps of respect for my braking markers, because basically there was absolutely nothing held in reserve – instead, what never worked very well to begin with got progressively worse, as the pair of tiny seven-inch/178mm single leading-shoe drum brakes fitted at each end (the extra one at the rear for Ehret’s sidecar use) faded massively, and began howling in protest! Probably no single aspect of two-wheeled engineering has improved so much in the past 75 years as brakes, and for a 150 mph motorcycle the Vincent’s stoppers were definitely on the weak side. Plan ahead! The fact that the Black Lightning didn’t stop very well was probably not conceived by the factory as being an issue, inasmuch as this was a motorcycle primarily designed to go fast in a straight line. Still, the Lightning won three Isle of Man TT races, as well as many short circuit events around the world, where presumably its massive engine performance coupled with rear suspension that was streets better than anything else on two wheels back then, more than made up for the braking deficiencies.

Its focus on straight-line performance was also perhaps one reason that the Black Lightning’s gear change was so awkward, so that thanks to the straight exhausts running under the right footrest, it was very hard to get my foot under the lever for downshifts approaching a turn. Patrick Godet had fitted a sort of extension sleeve to the hollow foot lever which helped a little, but it meant you had to take your foot off the rest to grope around under the lever to hoick it upwards in order to downshift under braking - a necessary assistance to those poor quality stoppers. The problem was probably caused by my modern riding boots being much more robust and protective than the soft, thin ones used back then, making the space left by Vincent between the pipes and the footpeg insufficient today.

Still, I was genuinely impressed how light and precise the steering was, and how much turn speed I could keep up even with the skinny 21-inch front tire fitted. “The Lightning is not a bike designed for racetrack use,” said Patrick Godet. “If you want to do road racing you must make an exhaust which goes underneath the engine so you can have a proper gear lever, because with the two straight pipes it is not nice for the rider. If you look at pictures of Black Lightnings being road raced they always had the gear lever raised higher, which was just as bad and is why we extended the lever. I never understood why they did that, since it has so much more performance that you don’t need to change gears very often – it goes in every gear!”

I’ll say. Throw a leg over the seat, and you’ll discover at once how low and narrow the Vincent is beneath you – it felt much smaller than a 150 mph bike of the Fab Fifties had any right to. The one-piece handlebar was quite narrow and flat, but with upturned ends which delivered a comfortable leaned-forward mile-eating stance, while still giving good leverage in the tight turns that proliferated at Carole. The Vincent’s low-speed handling was rather ponderous, though, with the distinctive Girdraulic wishbone forks’ pressed-aluminium girder blades describing a lazy arc as you leant into a turn, feeling all the while they were about to fold in on themselves. But this never happened, of course, and instead the handling became more assured as I upped the pace, with greater precision in steering than the relatively primitive telescopic forks of the day. No wonder John Britten and Claude Fior, two farsighted modern day technical gurus who are both sadly no longer with us, developed alternative versions of the Vincent blade forks three decades later for their exercises in alternative two-wheeled thought. By the standards of the day the Vincent’s ride quality was excellent, too, the cantilever rear suspension with a single hydraulic damper and twin spring boxes under the saddle eating up the few bumps on the Carole circuit.

But it’s that torquey, great-sounding 70 bhp V-Twin engine that’s the real star of the show in the Black Lightning. It made every one of those horses count in delivering a level of performance that, while more than satisfactory today, must have been truly mind-blowing by the standards of yesteryear. Acceleration was forceful above the 3,800 rpm power threshold, and with the crack of the straight-through exhausts echoing in your ear, it was a real thrill to wind open the light-action throttle and feel the wind on your helmet intensify as the needle cranked round that speedo parked in front of the rev counter. 75 years ago Phil Irving’s masterpiece motor delivered a level of performance nothing else could live with.

This Vincent Black Lightning was not just an ultra-desirable collector’s item, but provided an entirely faithful window on the refined but still raw-edged level of performance which Philip Vincent’s motorcycles delivered over seven decades ago. To be invited to ride such a historic and unrestored such bike, which was almost certainly the last 100% original example of the most desirable series production model ever made, by any manufacturer, was an act of generosity on the part of its then curator (as he described himself) Nicolas Dourassoff. Let’s hope that the ‘Polish Lightning’s’ new owner will ride and enjoy it, too – as sadly its late owner never did – rather than locking it up indoors as the mechanical objet d’art it undoubtedly is.

Become a Motorcycle.com insider. Get the latest motorcycle news first by subscribing to our newsletter here.

A man needing no introduction, Alan Cathcart has ridden motorcycles since age 14, but first raced cars before swapping to bikes in 1973. During his 25-year racing career he’s won or been near the top in countless international races, riding some of the most revered motorcycles in history. In addition to his racing resume, Alan’s frequently requested by many leading motorcycle manufacturers to evaluate and comment on their significant new models before launch, and his detailed feature articles have been published across the globe. Alan was the only journalist permitted by all major factories in Japan and Europe to test ride their works Grand Prix and World Superbike machines from 1983 to 2008 (MotoGP) and 1988 to 2015 (World Superbike). Winner of the Guild of Motoring Writers ‘Pierre Dreyfus Award’ twice as Journalist of the Year covering both cars and bikes, Alan is also a six-time winner of the Guild’s ‘Rootes Gold Cup’ in recognition of outstanding achievement in the world of Motorsport. Finally, he’s also won the Guild’s Aston Martin Trophy in 2002 for outstanding achievement in International Journalism. Born in Wales, married to Stella, and father to three children (2 sons, 1 daughter), Alan lives in southern England half an hour north of Chichester, the venue for the annual Goodwood Festival of Speed and Goodwood Revival events. He enjoys classic cars and bikes, travel, films, country rock music, wine - and good food.

More by Alan Cathcart

Comments

Join the conversation

Terrific read!

Great read! I have a friend who owns 9 Vincents but none a lightning. He rode them all over Europe back in the day and he and his wife used to race one that's a hack.