Head Shake - Dodging the Daft

In 1913, right before the start of World War I, there were at least 37 different makes of motorcycles being sold in the United States. Motorcycling was going strong, it offered an affordable, enjoyable way to see what was over that next hill, and many Americans did just that. Automobiles were around, but they were prohibitively expensive, while the motorcycle was affordable and available to the masses.

Take a moment and just peruse the advertising pages of this May 1913 issue of Popular Mechanics, you can get a sense of the excitement that came with this new era.

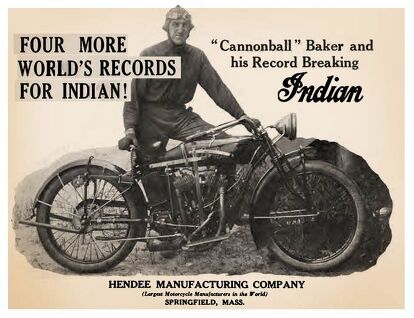

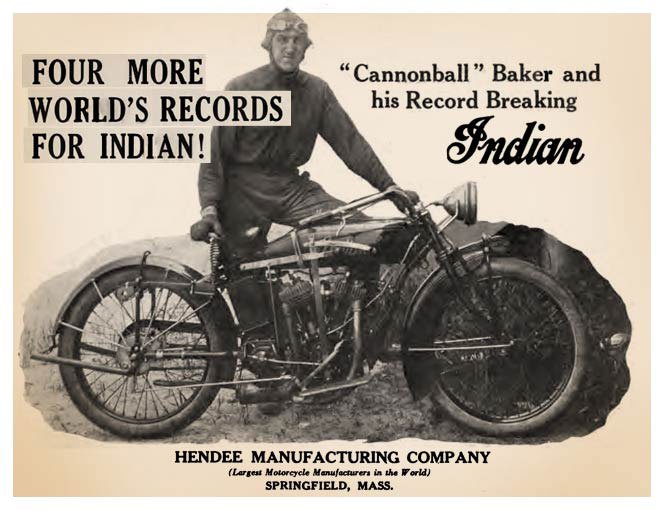

Just a year later, Erwin “Cannonball” Baker, set his first coast-to-coast record on an Indian motorcycle making the transcontinental crossing in 11 days. Try to imagine how that captured the imagination of folks of that era when for many people the farthest they had ventured from home may have been as far as a horse could travel in a day. The motorcycle redefined mobility and was available to almost anyone who could scrape up a reasonable sum.

Meanwhile, in Highland Park, Michigan, Henry Ford had different concerns. Never being one to leave well enough alone, he fiddled with an innovation that had already been around for awhile, but wasn’t all that efficient. He sought ways to improve the assembly line process, and improve it he did. He pioneered the moving assembly line, and the corresponding divisions of labor to complement it. Before long he was putting out a Model T every three minutes, every one of which he sold. And it is no wonder, what had been an expensive luxury, the automobile, was now accessible to the average working family; with rising productivity came plummeting costs. By the 1920s the Model T, which at one time would have cost an average worker two years wages upon its introduction, had dropped in price to a mere $240, 1/3 of what it had cost just a few years before, and less than many motorcycles of the day.

The dies and tooling were cast, Henry had seen to that, and the advent of the absentminded motorist was here to stay. Soon thereafter almost anyone could afford to go out, purchase a Model T, drive like an oblivious half-wit, and cut off a motorcyclist. We know there are two eternal truths: 1) Bikes are fun and, 2) Cars fail to yield the right of way to bikes. The century of the automobile had begun. And from every hillside and hamlet the call had been sounded, “But, but, but, I didn’t see him!”

This Hobbesian law of the right of way jungle went unabated for 50 years or so until a crank named Ralph Nader got all steamed about the Chevrolet Corvair and various other highway safety issues. He in turn got the American public all fired up. And the American public did what they always do when they get fired up: they demanded somebody do something. Congress, which generally takes it upon themselves to be those guys that, “do something,” at least at that time, actually did. They held hearings. There was much sturm und drang out of which was born the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), and a new thing called the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS). Somebody needed to promulgate those standards, and thus the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) came into existence. And then? Then we were off to the races.

The NHTSA was not one to sit on its keyster watching the world go by; so promulgate regulations, and conduct highway safety research is precisely what they did. They wanted to know more about motorcycle safety and the nature of motorcycle crashes. This desire led directly to what came to be known as the Motorcycle Accident Cause Factors and Identification of Countermeasures, Volume 1: Technical Report, or its abbreviated form, the Hurt Report, a landmark motorcycle crash study commissioned by the NHTSA, the scope of which has not been replicated to this day. The report was not published until 1981, but it’s likely the findings were coming in ever since USC professor Harry Hurt, David Thom and others had been on the streets looking at crash scenes since 1976-77. The Hurt Report confirmed what everybody who rode already knew: car operators didn’t see motorcyclists. A full two-thirds of motorcycle-car crashes occurred when a car pulled out in front of a motorcycle. This has remained constant over time.

If a car driver can’t see a human being on a 500-pound motorcycle, what can a rider do? Turn the headlight on; maybe they’ll see that, research at the time had suggested so. At that time, some states required lights on, some states did not. So NHTSA, seeking to harmonize a standard nationwide, got busy drafting a rule in the 1970s. They solicited public comment, and before the close of the decade, they had codified a rule specifying the standards that lighting must be designed to meet. This is the reason our lights come on when we turn the ignition on today. Small problem, though. Car drivers were still oblivious to what was going on around them, and they still pulled out in front of us as though we were invisible.

Mankind, and the aftermarket, always being ones to search for an answer, did just that, and they came up with another idea. If they can’t see us with a headlight on, what if we make the headlight flash all the time? So they built a headlight modulator. Some OEMs took notice and thought their customers might like it on new bikes, too — think disco dance floor flashing lights and you’re somewhere in the neighborhood. Surely they will see that.

There was a problem, the states had a hodgepodge of laws, some of which would consider headlight modulators illegal, so Harley-Davidson and a handful of aftermarket manufacturers petitioned the NHTSA for a new rule governing the flashing lights. The American Motorcyclist Association rallied their members to the cause and testified in support of the proposal. NHTSA obliged and a new rule was issued in 1985 after four years of deliberation, thereby standardizing the law across the country. And still they kept running into us.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, I knew guys that would mount up headlight modulators and Fiamm horns. They could go through an intersection flashing away like a tawdry disco on a Saturday night and sounding like a runaway logging truck out of Millinocket if they so chose. This was the extent to which some folks went.

Enter the 21st Century, the age of technology, and behold the promise of vehicle-to-vehicle communications (V2V). Much like Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) squawkers on airplanes announce their presence to any other aircraft in the area, V2V announces a vehicle’s presence to other vehicles in the area. This is an entirely new approach to the problem. If we can’t get their attention out here on the street by being illuminated, or blinking away for all we’re worth, or through apparently any means that anyone has been able to devise, maybe we can get their attention right where they live, in the cabins of their vehicles. Instead of looking and seeing us, which they have shown a century of inability to do, maybe their car can tell them, “Hey, Halfwit, wake up! There’s an approaching vehicle out here!” It is a different way of doing things, but who knows how the family transportation pod pilot’s brain works? It might just have some positive effect.

This is not a pipe dream. The list of players and the exhaustive research — to include motorcycles — that has been going on is impressive. Not surprisingly, Honda, whose engineers could put a man on Mars by the day after tomorrow if they so elected, has been out front on this from the outset. In fact, MO first reported on it here back in 2008, and Honda had been researching bike-borne V2V for the previous 10 years already.

The Motorcycle Industry Council donated a Honda Gold Wing and a Star Silverado to the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute for their field trials. Virginia Tech started research on this innovation back in 2001. They are not alone. The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute is conducting large-scale field trials that include almost 3,000 cars, trucks, and motorcycles. You name it, they are including it, everything from bicycles to semis. Thus far they have covered 25 million miles and they intend to expand the study to 6,000 vehicles. This is, in other words, a big deal. And the encouraging thing? This technology seems to work.

I know there will be some Big Brother concerns. Privacy issues are being discussed and should be addressed in the final rule-making process. But it is hard not to be encouraged by the possibilities this technology brings to the road. Aftermarket systems will be offered, and much like a generation before when riders were buying headlight modulators and Fiamm horns, buying a V2V system may be the safety equivalent of buying a Powercommander or Bazazz, and as simple as plugging it in.

The highway safety guys and engineers are leaving no stone unturned here. Researchers are looking into the viability of visual cues, heads-up displays, audio warnings, even vibrating seats that will do so directionally depending upon the location of the approaching vehicle. They are trying to ensure there isn’t information overload for the operator; too much info is as bad as not enough. The level of research, conducted and ongoing, has gone beyond exhaustive and entered the excruciating zone, and this is a good thing.

When fully implemented, car jockeys may still not “see” us, but the likelihood of them not seeing the visual cues on a heads up display, hearing audible warnings in the cabin of their vehicle, and perhaps even feeling us in the seat of their pants makes it almost inconceivable that they can ignore the presence of an oncoming motorcycle, and that is all for the good. Because when the dust settles, the biggest beneficiaries of all of this may just be us, the world’s most invisible road users.

About the Author: Chris Kallfelz is an orphaned Irish Catholic German Jew from a broken home with distinctly Buddhist tendencies. He hasn’t got the sense God gave seafood. Nice women seem to like him on occasion, for which he is eternally thankful, and he wrecks cars, badly, which is why bikes make sense. He doesn’t wreck bikes, unless they are on a track in closed course competition, and then all bets are off. He can hold a reasonable dinner conversation, eats with his mouth closed, and quotes Blaise Pascal when he’s not trying to high-side something for a five-dollar trophy. He’s been educated everywhere, and can ride bikes, commercial airliners and main battle tanks.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

I have on more than one occasion seen blind spot indicators blinking to tell drivers that I'm beside them (happened this morning when someone tried to merge into my lane). I'm thinking something similar could help out for pull out situations as a simpler (or at least intermediate) solution than V2V.