2014 Lightweight Naked Shootout + Video

Honda CB300F vs. Royal Enfield Continental vs. Suzuki GW250 vs. Suzuki TU250X vs. Yamaha SR400

Beginner bikes. Save for the obscure cruiser-ish thing you rode during your MSF courses, the two we hear more often than not for learning the moto-trade, especially if sporty-type riding is your thing, are the Kawasaki Ninja 300 (and formerly 250) and Honda CBR250R, now to include the CBR300R. However, we’re here to remind you there are other, potentially better, options.

What we’ve gathered for this test are five alternatives to the fully-faired, quarter-liter(ish) displacement category: the Honda CB300F, Royal Enfield Continental GT, Yamaha SR400, and two Suzukis, the GW250 and TU250X. All five have minimal bodywork, meaning the inevitable tipover won’t ruin fairings, all have manageable power, and all price tags all coming in under $6000.

Stylistically, the CB300F and GW250 represent modern, contemporary beginner-bike styling, while the Continental GT, SR400 and TU250X are old-school, representing bikes your dad might’ve started off on. Hell, your dad might still recognize the Enfield and Yamaha, as both are essentially the same bikes from 40-odd years ago. Right down to the kick starters (though the Continental also has a button).

We also have a wide range of engine choices. The GW and TU Suzukis have the smallest engines, at 248cc and 249cc, respectively, but the GW has the advantage of being a liquid-cooled parallel-Twin, whereas the TU is an air-cooled Single. Despite the name, Honda’s CB300F Single is really 286cc, placing it as the next largest engine here. It, too, has the benefit of liquid-cooling, but only the Honda can claim dual overhead cams. Next up is the SR400 and its 399cc Thumper. While relatively large in this class with its two valves air-cooling and single overhead cam, it hasn’t changed significantly since the Jackson 5 were big. Yamaha were at least nice enough to update it with modern fuel injection. So, there’s that.

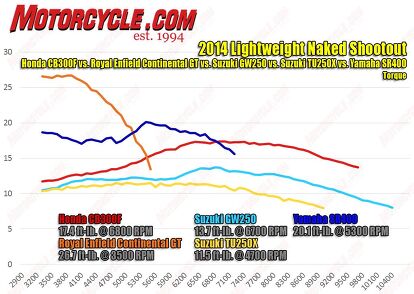

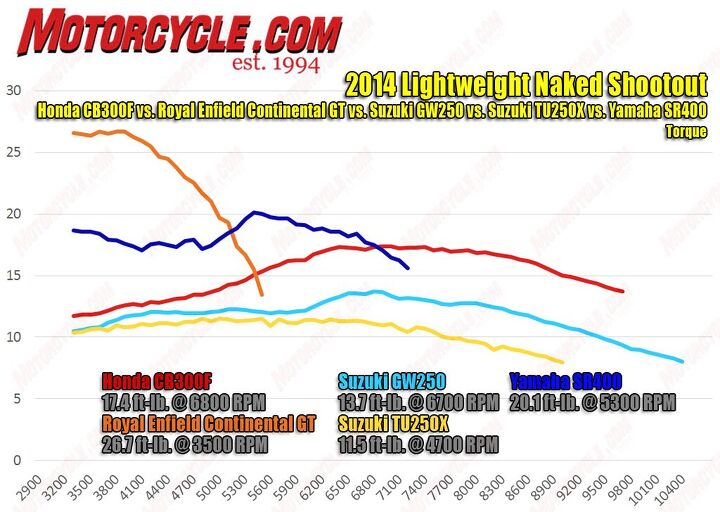

Leading the way in engine displacement is the Indian-made Royal Enfield, its 535cc Single towering over the rest. There was a time when engines like these ruled the racing landscape. Unfortunately, that time is long past, and like the Yamaha, the Indian copy of a British Single is virtually ancient in its design. That said, the big-displacement Enfield does boast the highest torque in the test, with 27.0 lb-ft., followed by the Yamaha (20.1 lb-ft.), Honda (17.4 lb-ft.), GW250 (13.7 lb-ft.) and TU250 (11.5 lb-ft.).

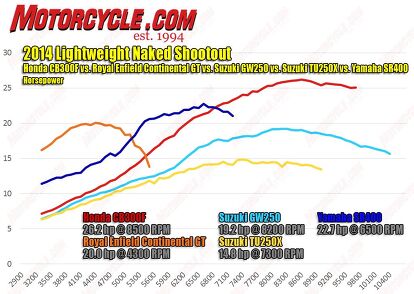

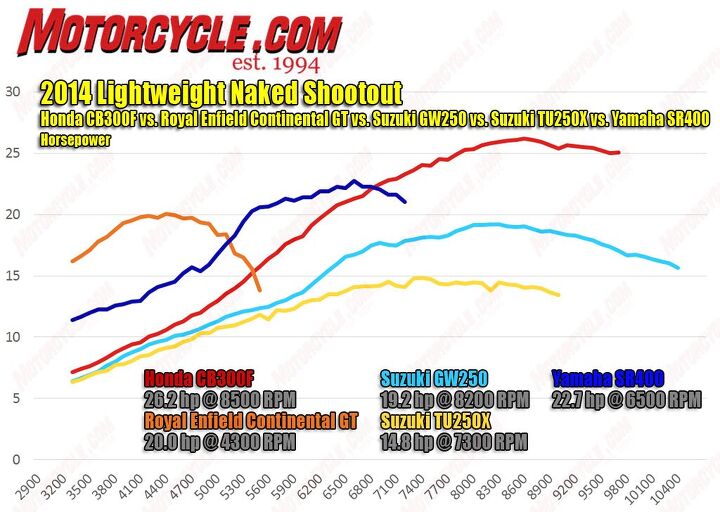

It’s not surprising to see the biggest engine produce the most torque. However, the benefit of newer engine designs is evident when looking at horsepower. Here, the 286cc Honda wins with 26.2 horses, followed by the SR400 (22.7 hp), Continental GT (20.0 hp), GW250 (19.2 hp) and TU250 (14.8 hp).

Power is not the be-all, end-all in determining winners. While true for every motorcycle, this is especially true in the beginner-bike market. A manageable seat height, light weight and agreeable riding dynamics are but a few of the things new riders will appreciate in small bikes. For this test, yours truly, along with Content Editor, Tom Roderick, and Kickstart Editor, John Burns, were joined by guest testers Thai Long Ly and Jessica Prokup. While your esteemed staffers all (vaguely) remember being noobs, Thai and Jess both are well tuned to the needs and concerns of new riders, with Thai having received his motorcycle endorsement only 18 months ago and Jess a former MSF instructor.

After putting all the bikes on the dyno and weighing them with full tanks of gas, we then rode them all in a mixture of urban and suburban environments, with a little bit of freeways and twisty roads thrown in for good measure. When all was said and done, we jotted notes, tabulated scores, argued amongst each other, and finally came out with results.

It should be noted that all five of these bikes make great beginner machines, and a certain personality may very well gravitate towards the bike we rank fifth over our winner. That’s perfectly fine, almost expected for the odd grouping we have. Here, then, is our ranking, from fifth to first.

It’s a shame the TU has to bring up the rear in this test. The elegantly styled retro bike is overwhelmingly competent in many areas. Four of the five testers gave it favorable reviews, with words like “fun” and “cool” being tossed around about how enjoyable it is to ride. Surprisingly enough, it handles, too. That’s right, the classically styled Suzuki is great for maneuvering through tight spaces or bends in the road. Credit goes to its feather-light 325-pound wet weight, the lightest in this test.

“This thing turned in at will and it reminded me of my Mongoose BMX bike from high school,” says Thai. “I found myself smiling the entire time I rode this little ferret of a bike.” Those sentiments were shared amongst most of the crowd, though curmudgeon Burns had other ideas. With not even 15 horses on tap (14.8, to be exact), the TU “doesn’t have enough power to stay ahead of traffic,” he says. It’s true, the TU is remarkably anemic, even among this crowd. Of course, leave it to Jess to find the TU’s silver lining. “Though not plentiful, power delivery is at least smooth and linear,” she says. Freeway speeds are still possible, but it’s wise to remain in the slow lanes when doing so.

That aside, the TU has all the fixings for a good beginner bike. Perfect fueling makes it easy for a new rider to learn clutch control. It’s low 30.3-inch seat height is the closest to the tarmac of this bunch, and even our short-legged guest, Thai, had zero issues touching down. From there, the TU scored a third-place finish in the transmission category, along with a second place in handling. We found it to be comfortable for an errand run, and were especially impressed with the 67 mpg it returned.

“You really can’t fault the performance of the TU,” Tom says about the TU’s competence. “It does everything it’s meant to do – turn, brake, accelerate – with unquestionable proficiency. For the novice, especially one who is slight in stature, the TU is simply the best bike on which to learn how to ride a motorcycle.”

However, what hurt the TU most in our scores was its price. At $4399, the Japan-built roadster is simply too expensive for its own good. Weighing in at $400 more than both the CB300F (built in Thailand) and GW250 (built in China), it certainly isn’t $400 better than either bike. Some, like Burns, see the weak engine as a liability. Also, the bias-ply tires have a tendency to follow rain grooves in the road. Its styling didn’t excite any of us, but we’d rather be seen on the TU than its stablemate, the GW.

“Seems to me the TU should be priced in the $3500 to $3700 price range, then it would be a lot higher in the rankings,” says Tom.

Fourth Place: Yamaha SR400. $5999It’s hard to ignore the novelty of the SR400. While it’s been a popular trend in both the auto and moto worlds to bring modern versions of iconic classics to market, the SR400 is pretty much the same bike Yamaha has been producing and selling since the 1970s, only updated with fuel injection and various emissions-related dealios. The styling has hardly changed, the controls look like they’re on the wrong side of 40, and even the kickstarter looks like it came from a ’70s parts pin. But if Yamaha thinks the market is clamoring for new old bikes from a bygone era, then the SR should be a hit. We aren’t so sure. But hey, at least it has a kickstarter. That’s cool, right?

At least until it’s time to start the bike for the second time (it’s cool the first time), and realize there’s no button to press. “The kickstart-only thing seems hip until it’s hot out, and you’re at a gas station trying to find top-dead-center before the 15-minute window – to ride home and get some luvin’ from your sweetie before the kid wakes up from his nap – closes,” said a pre-occupied Roderick. “If I wanted a motorcycle this authentic to the original version, I’d go buy the original version. Otherwise, give me electric start.”

The kick-start novelty wore off quickly for all our testers, even SR-loyalist Burns, who didn’t seemed fazed by it after the launch, “but this one’s not a first-kick starter like the one I rode on the launch, so…” From there, the five testers were largely mixed on the Yamaha, with the guest testers sharing completely opposite views from the jaded staffers.

Nowhere was this more apparent than when discussing the SR’s handling. Tom and I liked the SR’s handling in the tight stuff, its bars at a nice location to provide good leverage. Burns, too, was satisfied with its manners. However, Thai and Jess thought otherwise, the former complaining of dragging hard parts in corners while none of the other had this issue. “Disappointing,” was how Prokup described it. “Its cool vintage styling is unfortunately backed up by vintage handling and performance.” Admittedly, suspension is tuned for comfort, as they are for all the bikes here, but its bias-ply tires, like the TU250’s, don’t provide great confidence and track with rain grooves on the highway. “That spooked me in the ’70s and it still spooks me today,” says Burns.

By now we’ve established the SR is not going to win any vintage races, but that should have been obvious. It’s 30.9-inch seat height is the second tallest in the test, but that’s not really saying much. Nobody had any problems touching down on any bike here. The SR feels especially narrow between the legs, which helps promote the small-bike feel while also making it easier to touch the ground. At 381 lbs. with a full tank, it almost feels toy-like between the legs.

Engine wise, Burns, Roderick and your author found ourselves enjoying the power from the 399cc air-cooled Single. It makes due with its 22.7 horses quite nicely, with precise fueling all around. Ridden for what it is, there’s more than enough power to zip through town or country back roads. If you spend a lot of time on the highway then, “You spend a lot of time with this one at wide-open throttle,” says Prokup, “as it never seemed to have enough top-end power.” Burns points out that “it’s actually not a bad freeway cruiser, though it likes 65 better than 85 mph.”

Our main complaints about the SR400 center around its high-speed handling and lack of top-end power, neither of which would be a concern for a new rider, as their riding shouldn’t depend on either. If it does, then you’re looking at the wrong motorcycle. The SR400 might appeal to you if you feel you should have been born four decades ago, but like the TU250X Suzuki, a more pressing issue is its price. At $5990, “I’m having trouble justifying the $6k price tag for a kick start-only street bike,” notes Roderick. Prokup agrees, “The lack of electric start sucks for newbies, but it’s probably fun for experienced riders who like the novelty.”

Yamaha must feel confident in the number of new riders looking for something old school, or the old timers looking to rekindle a portion of their youth, to buy the SR400. None of these testers fit either description. As such, the SR400 lands in fourth place.

Third Place: Suzuki GW250. $3999Despite its decent third-place finish, the GW250 hardly left a lasting memory on our testers. On paper, the Suzuki GW250 boasts some impressive stats. At a dollar shy of 4-large, it’s tied with the Honda CB300F as least expensive motorcycle here. Its affordability is a large reason for its standing in this test.

It also sports a parallel-Twin engine, liquid-cooling and 17-inch radial tires at both ends. “Next to the Honda,” Tom notes, “the GW is the most modern bike here, and the only one with a gear-position indicator and fuel gauge indicators within its instrument cluster. It also has an adjustable front brake lever.”

Nice touches, yes, but at 248cc, it’s also the smallest engine here. With only 13.7 lb-ft of torque, “I’m not sure it could pull the hair off my chin,” says Thai. To really get any power from the little engine, it has to be spinning to stratospheric levels. It can do 80 mph, but you’re better off timing it with a calendar than a stopwatch. By that point, the engine is spinning to 9600 rpm — only 1400 revs shy of redline. While the rest of us were uneasy about revving the engine to the moon, odd-duck Burns comments, “Even up there, it’s not too buzzy at all. And unlike the retro bikes, it feels nice and stable the whole time as it’s on modern tires, and for me, the ride’s pretty smooth too.”

As you may have noticed, Burns often has the differing opinion from the other four testers, who weren’t as glowing about the GW’s handling. The GW’s 30.7-inch seat height is entirely manageable by all our testers, but it was also the second heaviest of the quintet at 407 lbs, full of gas. “That’s heavy for a 250, and it doesn’t hide it well,” says Prokup. When trying to flick the GW, Tom describes its turn-in response as “quick if not floppy.” All of us took some time to adjust to its manners, as constant input was needed after initial turn-in to maintain an arc. “The GW was less fun to ride than the TU,” Jess says. “Probably because it’s less flickable.” With a 56.3-inch wheelbase, the longest in this test, it’s no wonder why the GW felt less agile than the others.

The GW’s loose resemblance to the discontinued B-King – a monster of a naked hooligan if there ever was one – left us confused as well. The GW’s lack of power seemingly does the spirit of the B-King a disservice. “If the B-King were Tequila, the GW250 would be yogurt,” Thai says. “So why do they look the same? I don’t get it.”

Fine, we get that the GW isn’t a canyon carver or drag racer, but we’re still a little puzzled as to the GW’s purpose when used on a more normal basis on the street, other than being a decent starter bike for taller riders thanks to its “big bike” dimensions. She’s a decent ride, smooth and all, but gearing is short and tightly spaced together, requiring a 1-2 shift by about 15 mph. The rest of the cogs get shuffled through rather quickly after that. You’re well into sixth gear by 60 mph, meaning you’ll get plenty of practice shifting, even if you’re just making a burrito run. That said, it still returned 60 mpg. Impressive, considering how much time it spends revving to the moon.

Alas, because the GW was middle of the pack in many areas of the scorecard, it earns its third-place ranking. It’s cheap, smooth around town and even has a gear-position indicator. However, Burns would like to point out, “Everybody disses the poor GW, but for the same price as the Honda you get two cylinders, a bit more engine smoothness and almost a full-size bike.”

True, but the GW makes less power than the Honda. “I have no idea who’d want to buy this,” says Prokup. “It doesn’t have the goofy fun factor of, say, a Honda Grom, and doesn’t have the rideability of other bikes in its class. And the streetfighter-ish styling just seems garish.”

Second Place: Royal Enfield Continental GT. $5999If the amount of attention a motorcycle receives as it’s parked outside a coffee shop was enough to win a test, then the Royal Enfield Continental GT would win this test by a landslide. In fact, it’s the main reason it even achieved its second-place finish. It handily won the Cool Factor section of our scorecard, with the second place bike some 23 percentage points adrift. The classic cafe styling of the Enfield drew eyeballs at every stop, with onlookers asking to take a picture, chat about the bike and even have a seat on it. “Unequivocally the most attractive, charismatic motorcycle of the bunch,” Tom said.

If these onlookers actually got to ride the Enfield, their perceptions would likely change. Take Thai, for example. When given first crack at which bike he wanted to ride, he bee-lined straight for the Continental. His experience? “It was bloody hell,” he said. On the freeway, “the bars vibrated like they should’ve come wrapped in anonymous brown paper and my hands literally went numb about a mile into the journey.” Prokup referred to it as “wanting-to-jump-out-of-my-hands vibration.”

By the time everyone got their first taste of the 535cc Single, we thought for sure it would end up at the back of the pack. Its 27 lb-ft of torque made itself felt as the best in this test, and Burns noted he could be a little lazy with his shifting in the canyons because of it. The throaty exhaust note sounds killer as well, but that vibration — dear God, the vibration!

“Then, oddly, it grew on me,” Jess notes. A rider eventually realizes there’s a sweet spot “as long as you stay away from the 3500-rpm zone, where the vibes are debilitating” says Burns. Stay clear of that area and you can start to enjoy it. Around town, clutch pull is only slightly stiffer than the rest, but that isn’t saying much in this crowd because they all have light clutch pulls. The shifter can feel clunky at times, but we never managed to miss a shift. Otherwise, the Thumper makes easy work of the daily commute. The torquey engine thrives in this environment, leaping away from stoplights with ease. Unlike the others, the suspension was tuned more toward the firm side, meaning bumps in the road were felt more than the rest.

While a bit uncomfortable in the city, the slightly firm suspension made canyon work a lot of fun. Jess echoes our thoughts when she says “it was surprisingly stable in corners,” no doubt aided by the Pirelli Demon Sport tires. The cafe-style forward riding position gives the Continental tons of character, but it also lends itself to sporty riding. Roderick noted, “I liked the sporty riding position of the GT. For a taller guy, it provides as much room as the Honda with a more aggressive, forward leaning body positioning.” From there, the Enfield is graced with the best brakes of the five by a large margin. Stopping power was strong and the steel-braided line helped provide a firm lever. A nice touch.

Once we learned how to ride the Enfield in a way to avoid its vibey shortcomings, opinions started to shift. It’s the heaviest bike here, at 417 lbs, and its 31.5-inch seat height is also the tallest. Still none of us had any issues with the height or weight at a stop, and considering the archaic architecture of the 535cc Single (which, granted, has been upgraded to unit construction in recent years), there’s not a lot of power to worry about either. “That’s probably a good thing if newbies are considering this for a first bike,” says Prokup.

Six large is a little steep for a bike that could be fixed by a mechanic from the ’50s, but for the new rider with mechanical aptitude looking to get their hands dirty modifying their ride, the Enfield is a solid choice. “For owner involvement,” Burns points out, “I bet there’s lots of stuff you could improve – but the basic package seems really solid and it’s by far the coolest looking to me. If you’re after a little retro but not complete impracticality like the TU or SR, I think the R-E strikes a great compromise.”

Thai, too, is confounded by the R-E. “I’d have one to run to the store or to the market. Just to look ‘hella cool’ and be the coolest hipster in Silverlake. Except that wanting to be the coolest hipster in Silverlake in itself is so cool, it’s no longer cool, but sorta cool in an uncool way. See? Enigma. Royal Enigma.”

First Place: Honda CB300F. $3999While this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, the price-to-performance ratio the Honda CB300F provides just can’t be matched. It won nine of the 12 categories of the scorecard en route to an easy victory. Tom points it out quite simply: “It’s the newest model of the group, with the most performance, and full-size ergonomics for a price equal to that of the GW250. How can the Honda not win this shootout?”

Mechanically, we know it’s a good bike. The 286cc engine is a gem in this class, with near-perfect fueling, a capable chassis, comfortable ergos and an unbeatable price tag. What’s not to love?

“It [CB300F] felt the biggest and most mature of the group,” Jess notes. “Big” is obviously relative, as the Honda is the second-lightest bike, at 351 lbs, and its 30.7-inch seat height isn’t at all intimidating. Fit and finish is of typical Honda quality, which inspired Burns to write, “The only other bike of the five here (other than the GW) I would want to depend on as an only bike.”

Around town, the 300F is mostly unflappable, able to handle most situations with ease. The bars provide good leverage to maneuver through the streets, while simultaneously giving a nearly upright seating position. Fueling is mostly precise, though rolling at parking-lot speeds showed a slight hiccup at part throttle. Otherwise, “there’s plenty of power for freeway and canyons,” Jess writes. “It doesn’t seem like something a newbie would grow out of too quickly.”

Speaking of canyons, the CB300F was “decidedly composed” through them, says Thai. We expected that, but the Honda’s prowess shone bright when faced with the admittedly inferior handlers we brought along (save for the Enfield). The same bars that help the pilot navigate through traffic help the CB carve a corner, and the suspension “offers enough stability for an entry-level sportbike,” says Jess.

The only quibble comes from the CB’s stopping power. Tom writes, “in our Retro Roadster Comparo we toasted the CB1100’s stellar brakes against better-equipped motorcycles, and then here comes the CBR300F with just the opposite front-end braking performance. It’s squishy and lacking power.” But this might easily be fixed by fitting a toothier a set of pads and braided lines, and for the price, it’s easily forgiven.

Overall, for the new or newer rider not interested in history or tinkering, who is simply looking for a solid learning tool, our pick is the Honda CB300F. Thai sums our thoughts best: “It offers big-bike feel with little-bike thrill.”

2014 Lightweight Naked Shootout Specs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honda CB300F | Suzuki TU250X | Suzuki GW250 | Yamaha SR400 | Royal Enfield | |

| MSRP | $3,999 | $4,399 | $3,999 | $5,990 | $5,999 |

| Engine Type | 286cc liquid-cooled, single-cylinder, DOHC, four-stroke. 4-valves per cylinder | 249cc air-cooled, single cylinder, SOHC four-stroke. | 248cc liquid-cooled, Parallel-Twin, SOHC, four-stroke, | 399cc air-cooled, single-cylinder, SOHC, Four-stroke. 2-valves per cylinder | 535cc Air-cooled, single-cylinder, OHV, four-stroke. 2-valves per cylinder |

| Horsepower | 26.2 @ 8500 | 14.8 @ 7300 | 19.2 @ 8200 | 22.7 @ 6500 | 20.0 @ 4300 |

| Torque | 17.4 @ 6800 | 11.5 @ 4700 | 13.7 @ 6700 | 20.1 @ 5300 | 27.0 @ 2200 |

| Bore and Stroke | 76.0mm x 63.0mm | 72.0mm x 61.2mm | 53.5mm x 55.2mm | 87.0mm x 62.7mm | 87.0mm x 90.0mm |

| Fuel System | PGM-Fi, 38mm throttle body | Fuel injection | Fuel injection | Fuel injection | Fuel injection |

| Ignition | Digital inductive | Digital inductive | Digital inductive | TCI: Transistor Controlled Ignition | Digital inductive |

| Compression Ratio | 10.7:1 | NA | 11.5:1 | 8.5:1 | 8.5:1 |

| Transmission | 6-speed | 5-speed | 6-speed | 5-speed | 5-speed |

| Final Drive | Chain | Chain | Chain | Chain | Chain |

| Front Suspension | 37mm conventional fork. 4.65 in. travel | 37mm Showa telescopic fork | Kayaba conventional fork. Non-adjustable | Conventional 35mm telescopic fork. 5.9 in. travel | Conventional 41mm fork. Non-adjustable. 4.3 in travel |

| Rear Suspension | Pro-link single shock, preload adjustable, 4.07 in travel | Dual shocks | Single Kayaba shock. Preload adjustable. | Dual shocks. 4.1 in travel. Preload adjustable | Twin Paioli shocks, preload adjustable, 3.1 in travel |

| Front Brake | Single 296mm disc. Twin-piston caliper | Single 275mm disc. Two-piston caliper | Single 290mm disc. Twin-piston caliper. | Single 258mm disc. Twin-piston caliper | Single 300mm disc. Twin-piston caliper |

| Rear Brake | 220mm disc. Single-piston caliper | Drum | Single 240mm disc. Single-piston caliper. | Drum | Single 240mm disc. Single-piston caliper |

| Front Tire | 110/70-17 | 90/90-18 tube | 110/80-17 | 90/100-18 tube | 100/90-18 |

| Rear Tire | 140/70-17 | 110/90-18 tube | 140/70-17 | 110/90-18 | 130/70-18 |

| Rake/Trail | 25.3 deg/3.9 in | 25.5 deg/3.6 in | 26.0 deg/4.1 in | 27.7 deg/4.4 in | NA |

| Wheelbase | 54.3 in | 54.1 in | 56.3 in | 55.5 in | 53.5 in |

| Seat Height | 30.7 in | 30.3 in | 30.7 in | 30.9 in | 31.5 in |

| Curb Weight | 351 lb | 325 lb | 407 lb | 381 lb | 417 lb |

| Fuel Capacity | 3.4 gal | 3.2 gal | 3.5 gal | 3.2 gal | 3.6 gal |

| MPG | 58.5 | 67 | 60 | 56.7 | 59.3 |

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

For the GW to have normal spaced gears, you'd have to change the 14/45t sprockets to 15/35t. That's a lot of change. But at 14/45t you could ride at below 25MPH in sixth gear, which is kinda silly if you ask me..

It is seriously time to update this segment with a new test as the small displacement standard is a hot bike right now imho.