Wrenching With Rob--Chemical Soup: The Mystery of Detonation

Editor's Note--This is part of a "Wrenching with Rob" series, in which Vintage Editor and Technical Writer Robin Tuluie will discuss, in depth, technical and theoretical topics that make motorcycles function.

Since the previous Wrenching With Rob, Chemical Soup: The Meaning of Gasoline we've been besieged with questions and comments regarding the combustion process occurring in an engine. In particular, the discussion focused on the problem of detonation, commonly referred to as "knock," which is a very serious and detrimental problem when it occurs - usually the pressures exerted onto the piston top during detonation are much larger (but of a shorter duration, like a pressure spike) than the mean combustion pressure. Nevertheless they are very detrimental to engine life, as the continual high shock loading of the piston, rod, crankshaft and bearings is quite destructive.

Detonation is the result of an amplification of pressure waves, such as sound waves, occurring during the combustion process when the piston is near top dead center (TDC).

The actual "knocking" or "ringing" sound of detonation is due to these pressure waves pounding against the insides of the combustion chamber and the piston top, and is not due to 'colliding flame fronts' or 'flame fronts hitting the piston or combustion chamber walls.'

Let's look in some detail at how detonation can occur during the combustion process:First, a pressure wave, which is generated during the initial ignition at the plug tip, races through the unburned air-fuel mix ahead of the flame front. Typical flame front speeds for a gasoline/air mixture are on the order of 40 to 50 cm/s (centimeters per second), which is very slow compared to the speed of sound, which is on the order of 300 m/s. In actuality, the true speed of the outwards propagating flame front is considerably higher due to the turbulence of the mixture. Basically, the "flame" is carried outwards by all the little eddies, swirls and flow patterns of the turbulence resident in the air-fuel mix. This model of combustion is called the "eddy burning model" (Blizzard & Keck, 1974).

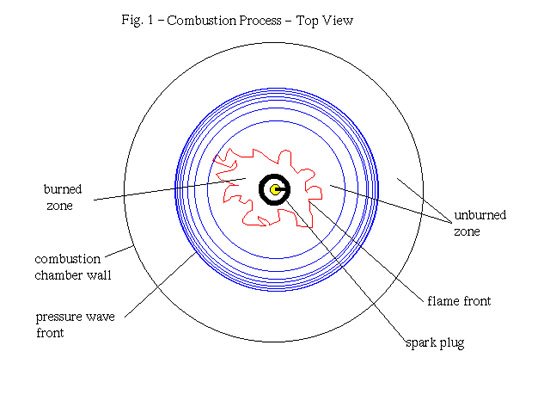

Additionally, the genus of the flame front surface - that is the degree of 'wrinkling' - which usually has a fractal nature (you know, those weird, seemingly random yet oddly patterned computer drawings), is increased greatly by turbulence, which leads to an increased surface area of the flame front. This increase in surface area is then able to burn more mixture since more mixture is exposed to the larger flame front surface. This model of combustion is called the "fractal burning model" (Goudin, F.C. et al. 1987, Abraham et al. 1985). The effects of this are observed in so-called "Schlieren pictures," which are high-speed photographs taken though a quartz window of a specially modified combustion chamber (Fig. 1, above).

Schlieren pictures show the various stages of the combustion process, in particular the highly wrinkled and turbulent nature of the flame front propagation (initially called the flame 'kernel').

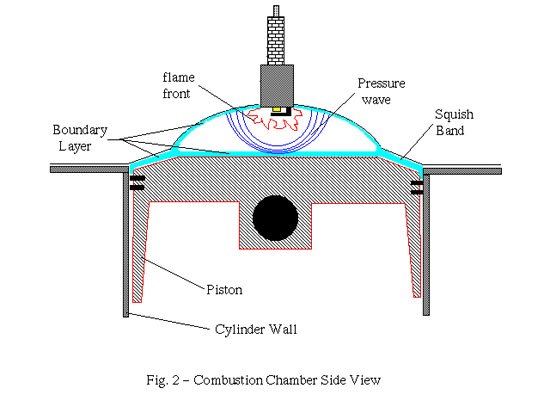

A higher degree of turbulence, and hence a higher "effective" flame front propagation velocity can be achieved with a so-called squish band combustion chamber design. Sometimes a swirl-type of induction process, in which the incoming mixture is rotating quickly, will achieve the same goal of increasing the burn rate of the mixture.

As a general rule-of-thumb the pressure rise in the combustion chamber during the combustion phase is typically 20-30 PSI per degree of crankshaft rotation. Once the pressure rises faster than about 35 PSI/degree, the engine will run very roughly due to the mechanical vibration of the engine components caused by too great of a pressure rise. Sometimes, the pressure wave can be strong enough to cause a self ignition of the fuel, where free radicals (e.g. hydroxyl or other molecules with similar open O-H chains) in the fuel promote this self ignition by the pressure wave.As a general rule-of-thumb the pressure rise in the combustion chamber during the combustion phase is typically 20-30 PSI per degree of crankshaft rotation. However, this can still occur even without the presence of free radicals; it just won't be quite as likely to happen. This is why high octane fuels, with fewer of these active radicals, can resist detonation better. However, even high octane fuel can detonate - not because of too many free radicals - but because the drastic increase in cylinder pressure has increased the local temperature (and molecular speed) so high that it has reached the ignition temperature of the fuel. This ignition temperature is actually somewhat lower than that of the main hydrocarbon chain of the fuel itself because of the creation of additional radicals resulting from the break-up of the fuel's hydrocarbon chains in intermolecular collisions.

Detonation usually happens first at the pressure wave's points of amplification, such as at the edges of the piston crown where reflecting pressure waves from the piston or combustion chamber walls can constructively recombine - this is called constructive interference to yield a very high local pressure. If the speed at which this pressure build-up to detonation occurs is greater than the speed at which the mixture burns, the pressure waves from both the initial ignition at the plug and the pressure waves coming from the problem spots (e.g. the edges of the piston crown, etc.) will set off immediate explosions, rather than combustion, of the mixture across the combustion chamber, leading to further pressure waves and even more havoc. Whenever these colliding pressure fronts meet, their destructive power is unleashed on the engine parts, often leading to a mechanical destruction of the motor. The pinging sound of detonation is just these pressure waves pounding against the insides of the combustion chamber and piston top. Piston tops, ring lands and rod bearings are especially exposed to damage from detonation. In addition, these pressure fronts (or shock waves) can sweep away the unburned boundary layer (see figure 2 above) of air-fuel mix near the metal surfaces in the combustion chamber.

The boundary layer is a thin layer of fuel-air mix just above the metal surfaces of the combustion chamber (see figure 2, above).

Physical principles (aptly called boundary conditions) require that under normal circumstances (i.e. equilibrium combustion, which means "nice, slow and thermally well transmitted") this boundary layer stays close to the metal surfaces. It usually is quite thin, maybe a fraction of a millimeter to a millimeter thick. This boundary layer will not burn even when reached by the flame front because it is in thermal contact with the cool metal, whose temperature is always well below the ignition temperature of the fuel-air mix.

More by Robin Tuluie

Comments

Join the conversation