The Legacy

In the summer of 1917, a 17-year-old young man in Atchison, Kansas, packed up his 1914 Excelsior Super-X Autocycle and headed for California

--just to see if the world, and this 64.9 cubic-inch twin was the company's first-ever with a two-speed transmission and a leaf-spring front suspension. A couple of years earlier, in 1912, the Excelsior had become the first motorcycle to circle the globe, and on December 30th of that year, Lee Humiston had become the first man to break the 100 mph barrier on his Excelsior Autocycle. Riders aboard the 1914 model had won virtually every national championship race in its inaugural year. By 1915, it would be advertised as "The Fastest Motorcycle Ever Built," having set new world records in the half-mile, mile, five-mile and 10-mile venues. Is it any wonder why a young man of 17 would lust after one? Even a non-running model?

By 1915, it would be advertised as "The Fastest Motorcycle Ever Built"

A winter of working in the unheated barn on the family farm had put the engine back into running

Along the way he camped out under the stars, and fished and hunted for his meals. Sometimes he would barter a bag full of quail or fresh-caught bass at a farmhouse, for a dinner at the farmer's table and warm place to spend the night. Some nights he just sat under his poncho in the cold rain, chewing on beef jerky. [Ohmagawd! That's our Fonzie, to a T.--Ed.]

The new-fangled chain drive on his Excelsior broke twice, and he repaired it with links he had fashioned with his own hands. Once, miles from nowhere, an engine main bearing went out, leaving him stranded. He walked the railbed for several miles until he found a Prince Albert tobacco tin, carelessly tossed out the window by some train traveler. Back at his camp, he whittled a piece of firewood into a bearing form, and then patiently hammered the tobacco tin over it until he had made his own replacement bearing shim. He did such a good job that after reassembly, the engine ran with the tobacco tin bearing for over 500 miles, until he could find a replacement.

He had no sponsors and no agenda. He just rode for the joy of riding.

Eventually, the young man made it to the coast, saw the ocean, waded in it for a few minutes, and then started back home. He arrived back in Atchison almost three months after having left, having ridden approximately 3,700 total miles. Though it was quite an accomplishment for him, personally, to the rest of the world it was hardly worth note. Especially since at the very same time he was making his trek, during July of 1917, a man named Alan Bedell, 21 years old, had set a new world's record for traversing the US, coast-to-coast in 7 days and 16 hours--also on an Excelsior Autocycle. Bedell actually rode about 500 fewer miles than the young man from Atchison, but he did it in record time, not to mention the cachet of going "coast-to-coast." It was a year of setting records for Excelsior, as Bedell would set another that year for the "Three Flags Classic," going from Canada to Mexico in record time, and another Excelsior rider, Roy Artley, would set a new 24-hour endurance record, riding 706 miles in a single day.

So it was that the young man's accomplishment faded into obscurity. Not that he cared--he hadn't made the ride for glory or recognition. He had no sponsors and no agenda. He just rode for the joy of riding.

Though he owned a few more bikes after that, and made a few more long rides, he soon found the girl of his dreams and settled down to a "normal" life. He stayed with the Santa Fe railroad for 50 years, retiring in 1965. The journal and the photos were locked up in an old steamer trunk in the attic of the house he built in Atchison, never to see the light of day again until the house was sold in 1967. The journal and the photos were locked up in an old steamer trunk in the attic of the house he built in Atchison, never to see the light of day again until the house was sold in 1967.

I graduated from high school that same spring, and had driven down from my parents' home in St. Joseph, Missouri, to help my grandparents move out of their house, to a retirement home they had purchased on Padre Island, in the Gulf of Mexico. I was up in the attic, clearing out stacks of old National Geographic magazines, when I came upon the rusted, old metal steamer trunk. The key was in the lock, but it took a bit of coaxing to get it open after 50 years of disuse. Inside, I found the old journal and the stack of faded photographs. I leafed through the photos in disbelief--Grandpa had never so much as mentioned even owning a motorcycle, that I knew of. Then I started reading the journal of Fred Rau, my grandfather.

Grandpa found me about two hours later, sitting in the attic surrounded by the scattered pictures, with the journal on my lap. "Why?" I asked. "Why have you never told me about any of this, Grandpa?"

"I was young, and a little crazy, I think," he said. "And your Mother and Grandmother have always been afraid that I would be a bad influence on you, if you knew about my wilder, younger days. So, I've just kept it in the past, where it belongs. You get older, you get responsibilities, and you learn to put the things of your youth behind you, for your family."

We talked for about an hour after that, and several more times in later years, when I went to visit him. He gave me the journal and the photos to keep, but he also gave me something much more important--exactly the thing that my mother and grandmother had feared--a burning desire to travel, to see and do things that most people just dream about. And his journal taught me to embrace and enjoy the adversities just as much as the pleasures of the journey. The adventure isn't complete without both.

"I was young, and a little crazy, I think," he said. "And your Mother and Grandmother have always been afraid that I would be a bad influence on you, if you knew about my wilder, younger days."

Two simple words were all he said: "Thank you." It was enough.

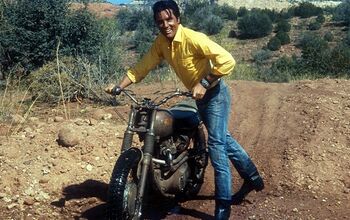

This past March, I was riding alongside a stretch of the old Santa Fe railbed that Grandpa rode 90 years ago. There's a section just west of Arrowhead Junction, alongside Goffs Road, about 15 miles north of I-40 near the California/Nevada border, where I am certain from his journal that he spent a night staring at the stars from his bedroll. I pulled my bike over alongside the tracks and shut off the engine.

If you've never been out in the desert alone, it is hard to imagine a quiet so intense. As I stood there beside my bike, I reflected on my memories of Grandpa, and on the legacy he left me. I'm not a particularly religious man, but somehow I felt he was watching, and appreciated the gesture.

More by Fred Rau

Comments

Join the conversation