After The Crash: Repairing Better Than Stock

Many different ways to source replacement parts for function and fashion

VerticalScope’s VP of Sales, Jason Brilant, has lived a variation of this scenario first-hand. While riding on a rural highway in the Allegheny National Forest, he encountered gravel on the road and low-sided his 2012 Ducati Monster 1100 EVO at about 50-60 mph and slid into a grassy ditch. Jason and his bike were banged up but not badly broken, and he was able to ride his cosmetically injured Duc the 220 miles back to his Toronto home. Functionally, the only impairment was a broken gear-shift lever that eventually and painfully wore its way through his boot during the ride home.

Once back at home, Brilant realized that, while his Monster was basically functionally sound, the cosmetic damage presented him with a pair of options: return the bike to stock or use this unfortunate situation to personalize his bike through the use of aftermarket parts.

The decision was clear once he itemized the list of damaged parts: headlight, left turn signal, left side tank cover, shifter lever, clutch lever, left bar-end mirror, left grip, instrument cover, left-side exhaust canister, and mild frame scraping. In the end, the only damaged component that was returned to stock was the broken shift lever.

Starting with the bodywork, the Monster received custom tank and fender set from a forum member on Ducatimonster.org for $670. Ducati replacement parts would’ve totalled $1,174. (Don’t forget to check out forums when repairing crash damage, particularly if you’re looking for OEM parts. Often, owners will remove these items when a bike is being customized or converted for track use.) Since they are custom painted OEM parts, the replacement was a simple bolt-on. The seat cover also displays a snazzy number plate design along with the dark grey pearl blue metallic. (Yeah, it looks black in the photos though it’s said to be really cool in person.) The Bestem USA front fender ($159) is carbon fiber – because Ducatis and carbon fiber go together like MO editors and Batdorf & Bronson coffee. Speaking of carbon fiber, the damaged left silencer ($435) for the Spark Exhaust Technology exhaust was replaced, too.

The borked clutch lever was updated with an aftermarket item off the rack in Brilant’s local dealership, as was the brake lever. Rizoma Reverse Retro aluminum oval bar-end mirrors ($110) and Rizoma Sport aluminum and rubber grips ($65) finished the hand-control upgrades. The frame strangely ended up scraped on both sides, and the dings need to be sanded and repainted with a Color Rite Aerosol Complete Repair Package ($80) that is color-matched to Ducati red. After a close inspection of the damage and thorough review of the kit’s instructions, Brilant thinks this part of the repair may be beyond his skill set, so he’s trying to find a friend with experience in paint repairs to help him do it right the first time.

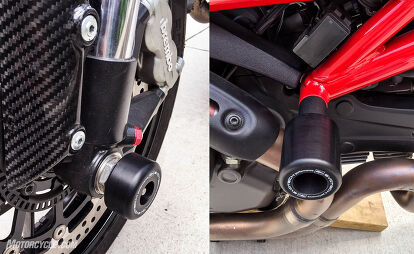

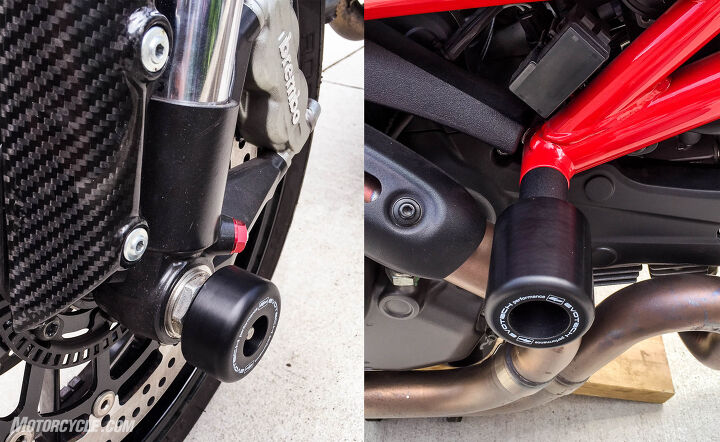

In an effort to minimize damage in any future tip over, Brilant installed a set of Evotech Ducati Monster 1100 EVO Crash Bobbins ($106) through the frame. A relatively easy process of swapping the OE engine mount rod with the longer Evotech item has only one tricky part. The engine must be supported with a jack (a small bottle jack will suffice) to keep it from shifting in the frame as one rod is replaced with the other one. With a support under the engine, the exchange is as easy as sliding the stock one out part way, then pushing it clear as the new, longer one slips into place. Once there is 3.5 in. showing on both ends of the rod, the assorted spacers, sliders, and washers are torqued down.

Since the Monster has a hollow front axle, installing the Ducati Monster 1100 EVO Front Fork Spindle Bobbins ($44) is as simple sliding the threaded rod through the axle, assembling the parts in the appropriate position, and torquing the nuts in place. In the event of a future mishap, these two parts should help to minimize the damage to Brilant’s Duc in a slide.

With the OEM replacement headlight and headlight frame tipping the scales at more than $700, Brilant made the executive decision to push his Monster’s headlight in the direction of a more traditionally roadster style round housing. His sorties on the web resulted in the choice of a LSL Headlight ($95) and the properly-sized LSL Headlight Brackets ($175) for his 1100’s fork tubes – both from Spiegler Performance Parts. Ordering the headlight itself was easy, but getting the right size clamps for the headlight bracket requires accurate measurements of the fork tubes at the point that the headlight will be mounted. In the case of the 1100 EVO, the clamps needed to be 50mm and 52mm to account for the widening of the fork tubes as they approached the lower triple clamp.

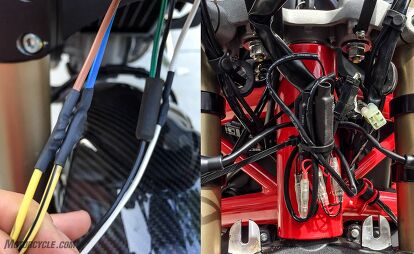

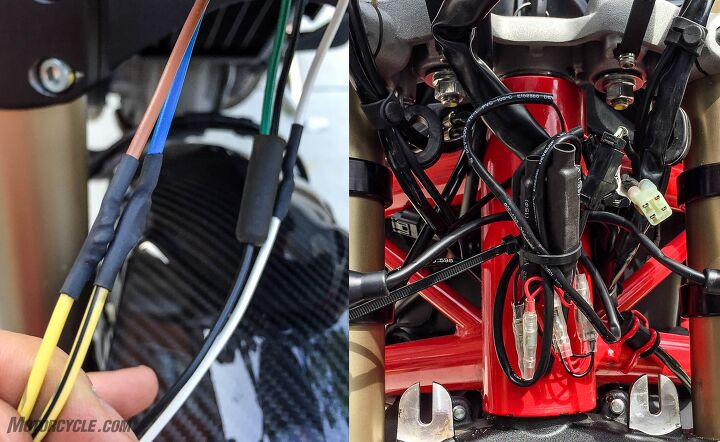

While physically mounting the headlight is bolt-on easy, once the right clamps are ordered, the wiring required a little detective work. While having a copy of the factory service manual’s wiring diagram can provide a map of what wires go where, any modification of a motorcycle’s wiring is a perfect time to practice measuring (and testing) twice and cutting once. In addition to grafting the headlight’s wiring into the new shell, the Duc’s front turn signals were being swapped from OEM incandescent units to small, sexy, and very bright Rizoma Zero aluminum-housed LED signals ($54 each). The front signals simply bolted to the hole in the LSL Headlight Bracket, and the resistors necessary to trick the Ducati into thinking it still had filaments in its turn signals were hidden behind the headlight shell.

The end result of Brilant’s Pennsylvania mishap is a Ducati Monster 1100 EVO that not only looks like it has never been crashed, but it also carries some of its owner’s personal flair. All-in-all, an attractive result of one very bad day.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

Thank you for this article. I too own a Monster and ride around quite a bit, have put in over 20,000km in two years..and am still scared of spilling it. What baffles me after riding bikes for 5 decades is, why are the OEM parts so expensive? When they make bikes in zillions, surely they must know what parts to produce in the same amounts.. the service parts and consumables (normal tip overs) at least. What IS this rip-off after the sales have been done?

Or you could ride it with bent handlebars and road rash. and only fix what is broke. . Remember you will have to do the same thing again after the next crash.