Triumph the Art of the Motorcycle Book Review

Triumph the Art of the Motorcycle

The Definitive Story of the Finest Motorcycles Ever Made

By Zef Enault and Michael Levivier

When it comes to motorcycle books, probably no other marque has been more well-documented than Triumph, but if you had to have only one Triumph book to bring you from inception to 2017, this one would have to be it.

Siegfried Bettmann and Mauritz Schulte, a pair of Germans who’d emigrated to England in the 1880s, dealt in White Sewing Machines and bicycles before combining forces and changing the company name from Bettmann Importing & Exporting to Triumph. They built their first motorcycle in 1902 by inserting a 211cc Belgian-sourced Minerva engine into a modified bicycle frame.

By 1907, Triumph was producing 1000 motorcycles a year, helped along by Bettmann’s salesmanship. He’d added 200 more salesmen to his staff and a pair of riders to take part in long-distance rallies, shortly after 376 new motorcycle brands had appeared at the 1903 London Trade Show. In 1907, Triumph took second and third in the first Isle of Man TT. In 1908, Triumph’s new 3.5 HP, with all-new two-speed transmission, won the TT outright. By 1913, the German immigrant Bettmann had been elected mayor of Coventry, in which Triumph’s Priory Street Works would expand to 310,000 square feet and employ up to 3000 workers before smacking up against the Great Depression in 1929.

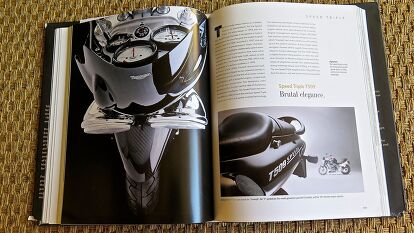

Maybe it was all too much too fast; Bettmann’s new automotive division was already heavily in the red by the time of the Depression, and by 1936 the owner of rival Ariel was able to buy the Triumph motorcycle division for just 5,000 pounds. Jack Sangster promptly made one of his Ariel engineers Triumph’s new managing director, Edward Turner. Turner begat the 1938 Speed Twin. The rest, as we’re so fond of saying, is history – and all of it is covered and lusciously illustrated in the first 79 pages of this 240-page, 10 x 12-inch coffee table tome, complete with special sections highlighting interesting Triumph projects like the Texas Cee-Gar, the X75 Hurricane, etc.

As much as all this information has been previously covered, it probably makes perfect sense that the remaining two-thirds of the book deal with John Bloor’s resurrection of the company, beginning in 1983. And since it was created with Triumph’s assistance and its foreword is by Triumph CEO Nick Bloor, son of John, it’s no surprise that it’s as much a great big glossy Triumph brochure as much as it is a history of the company. Maybe you could get that from the subhead: “The Definitive Story of the Finest Motorcycles Ever Made”

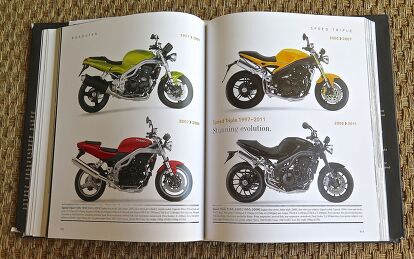

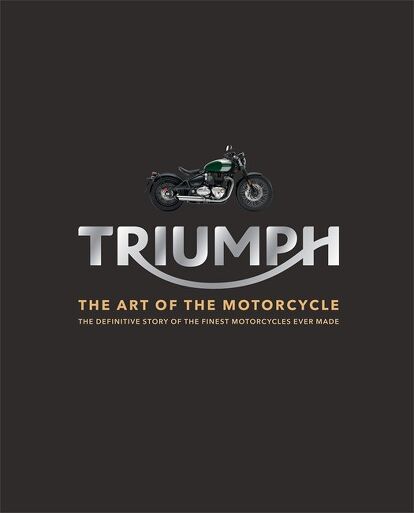

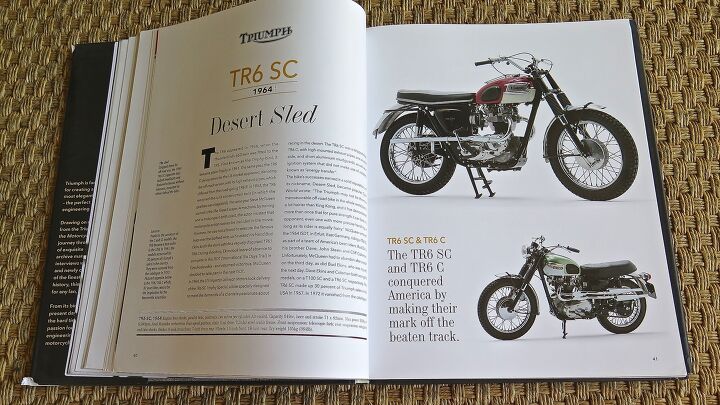

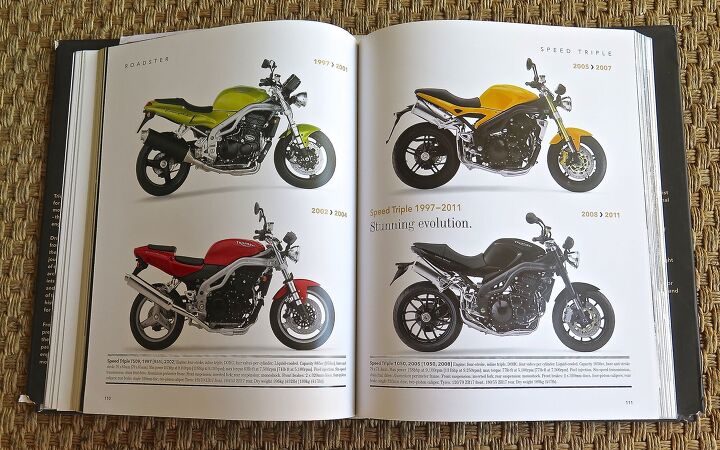

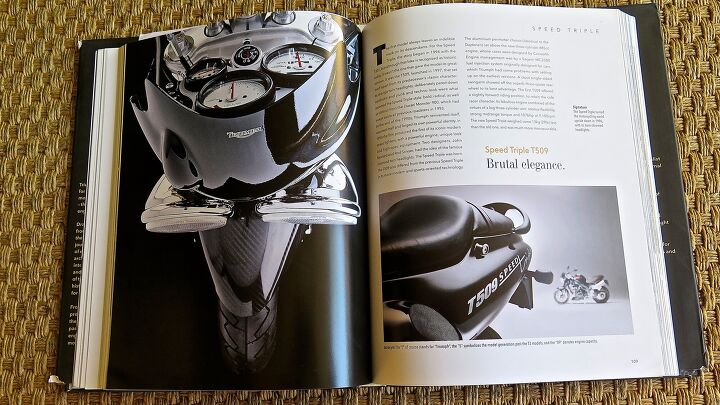

Not that that’s a bad thing. Many of the photos are ones we’ve seen before in Triumph advertisements, and if some of the language verges on the self-congratulatory, well, the Speed Triple really is a “legend” come to think of it, though maybe not the original 1994 T301 ST to which the book’s authors apply that descriptor. Still, there’s plenty of insider information about development of what seems like every Triumph produced since the first “new” Trident 750 and 900, launched in 1991.

Since the authors are a couple of journalists who worked for France’s Moto Journal, I for one am left longing for a little more of what the press and public response was to at least a few of the bikes; mostly all we get is the company line. Not always, though. Of the unremarkable 2000 TT600 four cylinder, Enault writes, “Where the TT600 went wrong was in its bland styling and its engine architecture. The choice of a four-cylinder unit, when fans expected a (more British) three-cylinder, put buyers off. Triumph would learn from this, and the TT600 brought about a shift toward bikes with a more marked identity.” Street Triple 765, anyone?

Other stumbles along the way were remarkably few, but the biggest was the 2002 fire that destroyed the Hinckley factory. Even that John Bloor capitalized on: “Bloor took advantage of this event to re-evaluate the company.” Mckinsey and Company sent him a team led by a 27-year old Dane named Tue Mantoni. “Sometimes you need a shock like that to make you tell yourself, `Okay, what do we want to do now?’ So we took advantage of the situation to create our own market niche, to really underline the difference between us and the Japanese bikes.” From then on, Triumph built Twins and three-cylinder engines only.

From humble beginnings right up to the new 2017 Bonneville Bobber, every model seems to be in here. And while many of the photos have been widely circulated recently online, their newness will rescind with time. Also, many of them are really, really beautiful photos. It’s nice to have them all gathered up on beautiful thick, glossy paper in one place, increasingly so as time goes by. If you’re into your Triumphs, this big juicy book will be £40 well spent.

- ISBN: 9781784723712

- Publication date: 05 Oct 2017

- Page count: 240

- Imprint: Mitchell Beazley

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

In the UK the 1994 T301 has reached legend status. These are sought after bikes now that are appreciating in value. Parts are sought after too.

I’m just always amazed at John Bloor’s success in rebuilding Triumph back to the major player it is. From essentially zero to hero in a quarter century. Think of the other brand resurrection attempts that have failed - some multiple times.

I hope Triumph can keep it going and maybe add a more stable dealer base. I’ve become a real fan of their modern bikes (have owned three of them)

Oh, and i’d argue the Speed Triple didn’t come into its own until the 955i engine.

This book will be in my Xmas list.