Skidmarks - Worse Than Nothing

“It’s clear to me that more of us are dying because there are too many people who really shouldn’t ride motorcycles and the industry and advocacy groups do nothing to discourage them.”

CityBike Magazine, August 2012.

Is formal rider training worse than nothing?

Back when the Hurt Report came out, there was almost no formal rider training in the United States, and that was one of the factors Hurt predicted would reduce fatalities if it was instituted, along with helmets and a few other things. Thirty years into state-sponsored motorcycle training, how did that work out?

Not so good. Despite millions of motorcyclists attending state-sponsored motorcycle training courses in 50 states since the late 1980s, motorcycle fatalities per vehicle mile travelled (VMT) or per million population, seems to be higher than it was in the early 1980s.

I’ve written about this before. Some well written and thoughtful responses to those columns asked, unless you compare trained riders vs. untrained riders, how do you know the rates wouldn’t have been even higher? A good point, but let’s get real, homies: if the Motorcycle Safety Foundation (MSF) considers a mere doubling of the fatality rate a success, I’d hate to see what it considers a failure.

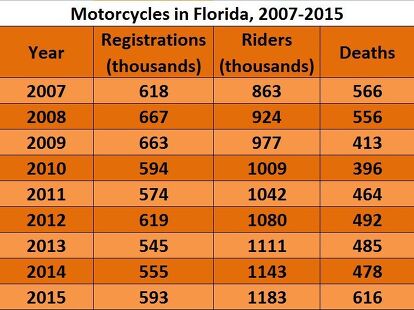

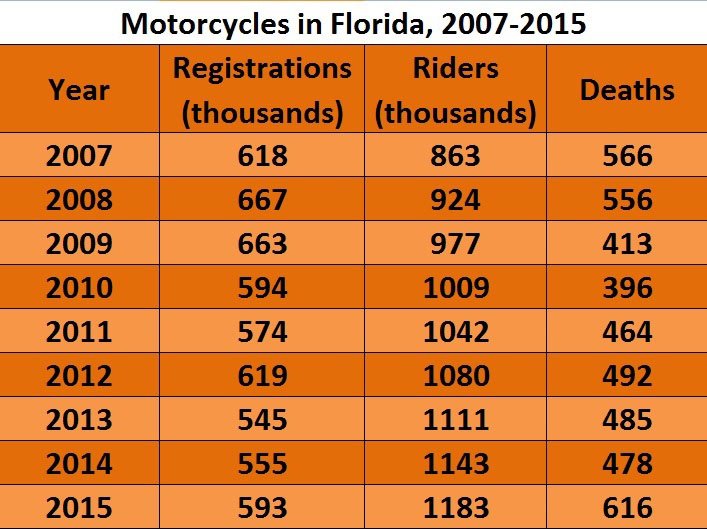

Well, if only that training was mandatory, we could reverse this trend. Funny you should say that, because in Florida, there was a dramatic 23% increase in fatalities between 2014 and 2015, despite the state requiring all new riders to take the MSF course since 2008. In fact, now, after eight years of mandatory MSF classes in Florida, the Sunshine State is second to none in motorcycle fatalities, despite having a third fewer motorcycles than the number-one state, California. Oh, but there’s no helmet law in Florida (repealed in 2000), right? Well, half the fatalities were helmeted riders, so, nope, that’s probably not (completely) it. Of course, we don’t know how many of those additional 138 fatalities in Florida had been trained by the MSF (or if they had been trained at all), so this could all be a fluke.

Why has training millions of riders seemingly made things worse? When I asked the MSF this question, the media relations department responded with, “There is no research available that explains why motorcycle fatalities increase in some states and decrease in others. It is impossible to objectively report why crashes/fatalities may have increased.” Impossible, they say. What do you think they are, some kind of 45-year-old organization devoted to motorcycle safety? When I pressed for clarification, I did not receive a response. The oracle has spoken.

If you were to ask me that question, I’d say that not only is the MSF course too easy to pass, imparting false confidence, it does nothing to discourage people who have no business riding. It’s easy to draw the conclusion that it’s because the motorcycle industry itself is the sole owner of the MSF (the Motorcycle Industry Council, itself funded by the biggest players in the motorsports industry, owns and actually shares office space – 2 Jenner, Suite 150, Irvine – with the MSF), a clear conflict of interest. I assume the MSF will say there’s no connection between who funds the organization and its goals, other than sharing the breakroom fridge, but I’ll let the organization speak for itself.

Of course we should have rider education. But we need to discourage, not encourage, some new riders from joining our ranks. I said it five years ago: the reason we’re dying is that there are too many people riding who shouldn’t be riding. Requiring training, especially from an inexpensive, easy-to-pass 15-hour class, is a sure way to increase ridership – and fatalities. Until training providers actively and enthusiastically discourage the unfit from riding motorcycles, training will be as effective as a parachute made from bowling balls.

That’s right, because even in Europe, where training is challenging, lengthy and expensive, it’s still not clear if it’s helpful in reducing fatality rates. The MAIDS study, done in Europe in the late 1990s, found little to link training to reduced accidents. Even in Germany, where mandatory rider training costs over $1,000 and takes weeks (and is done on public roads, including night-time riding on the Autobahn), authorities can’t really say for sure if teaching those skills save lives. Insurance companies are also unimpressed by the effect of training, preferring to push helmet laws and ABS brakes (which unambiguously reduce crashes and deaths) to bring down the mishap rates.

But don’t despair! There’s a glimmer of hope. In California, fatalities actually dropped 11% in 2015, even though the national rate was up 10%. What could have caused this? The Governor’s Highway Safety Association (GHSA) in its 2015 report speculated it may be that the country had a warmer, dryer winter, cheaper gas and more bikes on the road from a recovering economy. The folks at the GHSA don’t read my column (probably because they’re governors, and have to look busy all the time), because if they had they would have noted that the California Motorcyclist Safety Program (CMSP) also adopted an all-new training curriculum, headed up by friend-of-MO (full disclosure, a friend of mine as well) Lee Parks.

More full disclosure: I’ve taught both curricula (Latin scholars, please note correct plural of “curriculum:” you’re welcome) in California over the last eight years, so I can tell you there are significant differences that, if motorcycles aren’t banned for being absurdly dangerous first, may at least return us to the 1990s safety-wise.

First, the riding-skills evaluation is tougher to pass, which means the graduation rate is lower than the old curriculum’s. According to Lee, 6.5% of the Motorcycle Training Course (MTC) students failed to graduate in 2015, compared to 3.6% of the MSF’s Basic RiderCourse (BRC) students in 2014. Life-saving skills, like emergency braking, are weighted more heavily, and you have to really know technique, not just fake it by mimicking the rider in front of you. And also consider that students get almost double the riding during the class – 22-30 miles in the MTC, compared to 12-16 miles in the BRC, six of those miles just riding curves. They’re better trained, much more practiced, and still fail more frequently. It’s not a slam-dunk anymore.

It’s also tougher for more casual students to take the class. The ranges I work for charge drop-outs and failed students if they want to come back to try again – in the old days it was free, as many times as you wanted until you passed (I know one student who took it eight times). There’s also less of an “everybody pass!” culture among instructors – we’re encouraged to weed out people who lack focus, concentration, stamina or even strong desire by confronting them and having them honestly self-assess if they want to continue. Some instructors even (quietly) brag about how many students they fail.

The increased seat time and weeding of the non-hackers makes it a better program, if you ask me, but what makes me feel better about being a CMSP instructor is the honesty of the message. “Motorcycles are more dangerous than cars,” we tell the students. “Duh!” they reply. “Do you know how dangerous?” we ask. “Double?” “Two and a half times?” Nope, we say. Thirty-eight times more dangerous than cars. Erp! A sobering moment as 20 or 30 adults absorb that message. Sometimes students leave on the spot. Sometimes they leave after they drop the bike the first time on the range. But leave they do, and that makes me feel like I’ve promoted motorcycle safety, because there’s at least one person I know will never leave a bloody smear on Highway One.

More training? That means more riders on the road, and that’s a sure path to more fatalities. Sorry, motorcycle industry (and everybody who loves seeing happy riders out on our byways), but you can’t have your booming motorcycle-market cake (with trained rider frosting) and eat it guilt-free, too.

The name Gabe Ets-Hokin can be made into many fun phrases including snakebite hog, goatskin he be, and he go beatniks.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

Before we get twisted around the death stats, it might be helpful to get other sorts of data - like the profile of bike type highest in fatalities, the rider profile, and lots of other stuff. When you want to understand a topic well, you need more than a couple of data elements.

Certainly, one class in physics doesn't make one a physicist; and one motorcycle safety class doesn't make one a skilled rider. Ergo, as one poster said, it would be helpful to know the previous riding experience of the new rider. Those who had an extensive dirt riding history from childhood learn a lot from MSF or the Lee Parks Out of Control class. When I was teaching or coaching, you knew how things were likely to go depending on the background of participants. When a class was chock full of dirt riders from childnood - it was all easy. When we had a blended class, it was often boring for the experienced - and they didn't get the benefits they could have from a more intense "basic" class.

There should be more range and even street work for the safety classes. Much more. I'd say double or triple it. Expensive? Yes. But so are fatalities and disability due to injury. Look at the Europeans, a tiered licensing system - which I'm not advocating - but there needs to be much much more range work, and public road work.

We're an increasingly urban society. It used to be that rider types did dirt work before the street - not so much anymore. Same with manual shifting. And we're not even talking about the electronic safety controls that are now so prevalent on newer bikes that reduce the amount of skill required of riders.

Let me tell you, it's a lot more complicated that one class. And it's also not helpful to be proud of scaring new riders away. What you're really saying is we don't have the time to really train you, so are you willing to learn on your own on the mean and dangerous streets out there?

That is stupid. Sure there are folks who should not be riding. But the majority who want to can, and can do it safely. It simply takes much more time than MSF provides in the course. And we need to look at other data that is relevant, like looking at riders who do not crash and do not get injured - what is different about them?

The real answer is more data, and more training. It should be mandatory. An introductory course is not sufficient.

One other item of note: When I was a motorcycle safety rider coach, I happened to go on a tour of California with a good friend and excellent rider. One day, in the Sierras we were debriefing the day's ride. I pulled out my tablet and popped in the SD card with videos of him in front of me. Just after he finished saying he thought he'd done some of the best riding ever, he had the opportunity to critique himself in the video. I knew he'd been over-cooking speed and then slowing down, riding was not smooth. When he saw himself, he realized what he was doing wrong - and noted it was the worst riding he'd ever remembered doing.

Well, this sort of experience is what new riders need; that is to see themselves and what their riding looks like. But this means riding on the open road with someone tracking their moves on video, and hopefully also both using helmet to helmet communication. Those techniques really help them learn. I would advocate that on the street - because there is where the danger is at. Track days are for fun and some skill, but the danger of the road is not there, and folks need to learn.

I wanted to set up a business of working with new MSF grads so that they could learn and improve, but realized quickly the risk and liability factors that could make it very costly for the coach. But that is what new riders need - on the street practice with an experienced rider behind them. And you know from their credentials if they're the right person - they don't crash and have avoided accidents for year upon year.