Skidmarks - Squished?

Behold: the future

It’s a cute, fuzzy lil’ harbinger of the end of Life as we Know it: the Google self-driving car. Seriously. Right now you may think of it as a curiosity, a gimmick, but it could alter the physical, economic and cultural landscape of America in a way we haven’t seen since … well … the invention of the car in the first place. But what will that do to poor little us on our motorcycles?

First, let’s make sure you understand how far autonomous vehicles have come in 10 years, just in case you’re one of these people who bases technical arguments on things you learned reading ancient back issues of Popular Mechanics while waiting for the dentist. Back in 2005, I wrote a story about Anthony Levandowsky, the student leading the U.C. Berkeley team running a motorcycle in DARPA’s Grand Challenge, an off-road race between robotic vehicles. The article has been swept down the MO rabbit hole (although a Kawasaki enthusiast forum reposted it before it was wiped, at least one example of copyright infringement benefitting mankind) but the crudeness of early autonomous vehicles is remarkable. The Blue Team robot, a tiny pitbike that could barely get around a small track without hitting anything, is comical to watch in action, even if it did have amazing technology packed into it. It’s like watching a drunk and mentally handicapped invisible teenager ride an XR70 across your lawn. Even the winning vehicles that year seemed confused, slowly picking their way across a smooth desert.

The winner that year was a blue Volkswagen Touareg named Stanley, engineered by a Stanford University team led by Sebastian Thrun. After the Grand Challenge, Thrun, Levandowsky and other geniuses kept working on autonomous vehicles, but this time for Google instead of the Defense Department.

By 2013, Google’s fleet of autonomous test vehicles had driven – with little or no human intervention – hundreds of thousands of miles on public roads. New Yorker reporter Burkhard Bilger described Levandowsky’s Lexus as it drove him from Berkeley to Palo Alto (Levandowsky’s daily commute):

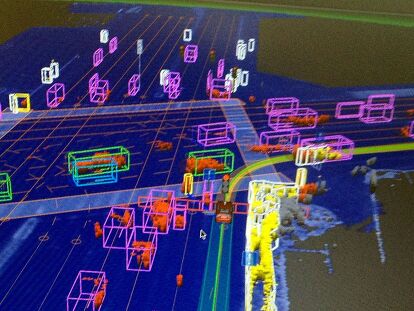

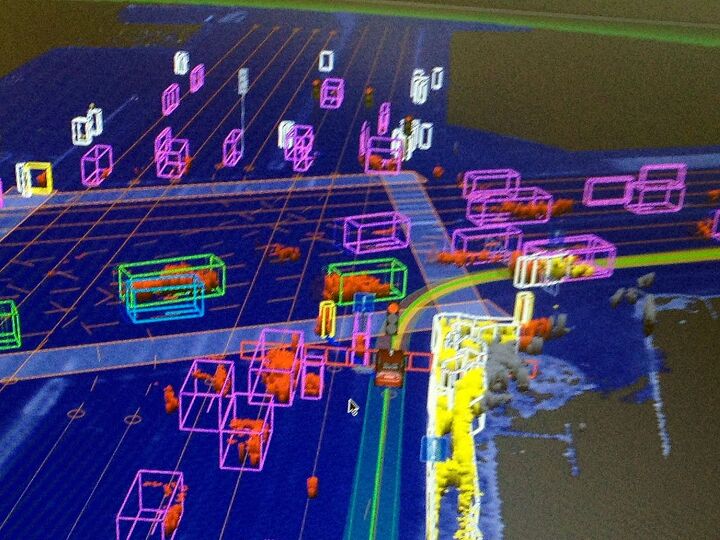

“Levandowski kept a laptop open beside him as we rode. Its screen showed a graphic view of the data flowing in from the sensors: a Tron-like world of neon objects drifting and darting on a wireframe nightscape. Each sensor offered a different perspective on the world. The laser provided three-dimensional depth: its 64 beams spun around 10 times per second, scanning 1.3 million points in concentric waves that began eight feet from the car. It could spot a 14-inch object a hundred and sixty feet away.”

Last year, Google announced it was building a test fleet of about 100 of the cute little bug-eyed prototype electric self-driving cars you see in the lead photo. They’re limited to 25 mph and have a 100-mile range. Inside are two seats, a small storage compartment, a computer screen … and that’s about it. A modest first step, but how many years will those 100 cars have to drive around on the busy, challenging roads of the San Francisco Bay Area before Google perfects robot vehicles? Five? 10? Not 20, I’d bet.

Futurist, Zack Kanter wrote a compelling blog entry about the impact this will have on the world. Combining this technology with the new “ride-sharing” craze could pretty much eliminate the need for privately owned cars. If you could go anywhere you wanted in an on-demand private transportation pod for a few pennies a mile, and didn’t have to worry about parking, gas, insurance, theft, tires or the hundred other hassles associated with car ownership, why would you want to spend the thousands and thousands of dollars to own a car, a car that will probably spend 96% of its time parked, according to a report issued by Morgan Stanley Research. Seriously, why?

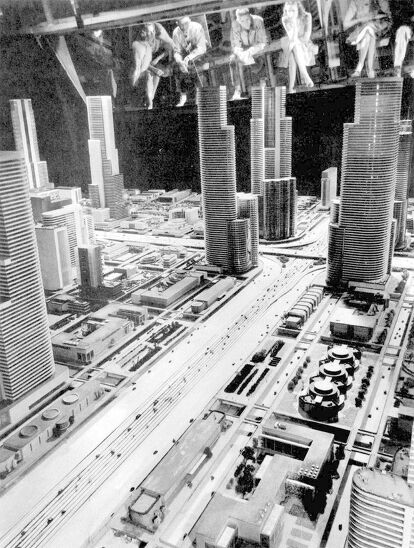

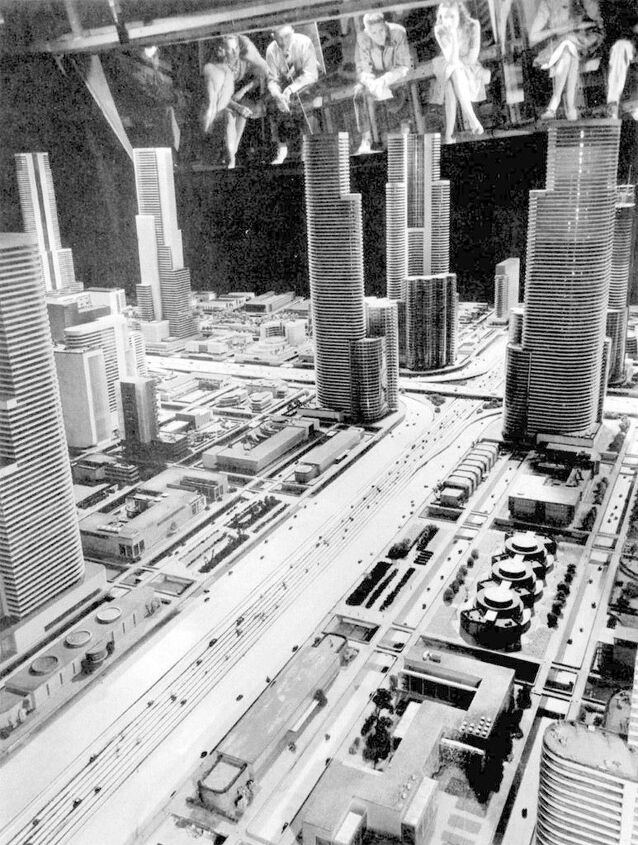

The economic changes brought by shrinking the personal-transport fleet 90% could be staggering. City streets and highways will narrow to single or double lanes. Parking garages and lots can be converted to other uses, and cities can get much denser by converting garages to in-law apartments (and I firmly believe only in-laws should be made to live in them). Look at an aerial view of your urban area and estimate how much of it is given over to cars – roads, automotive dealerships and other businesses, parking lots and garages – and subtract 9/10ths of it. Suddenly, even downtown Seattle or Chicago could be verdant and spacious.

Kanter’s predictions are both dystopic and utopic. Ten million driving and other automotive/transportation jobs will disappear, but miles and miles of city streets will be clear of useless, ugly parked cars. Billion-dollar corporate institutions will be bankrupted, but millions of traffic accidents will dwindle to a relative handful, saving thousands of lives and billions of dollars in property damage and human injuries. Traffic jams will become a memory – as will buses, subways and streetcars.

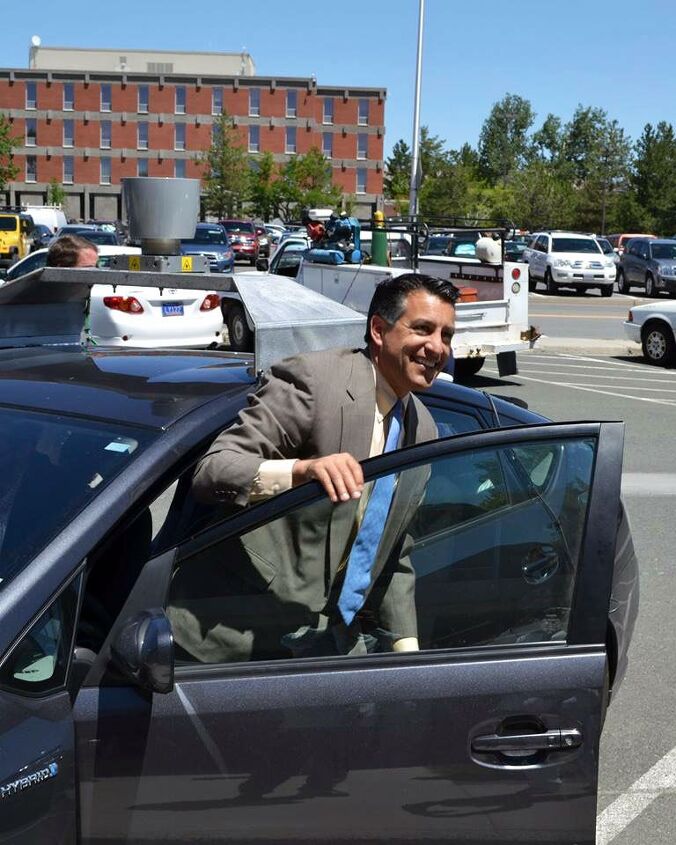

Kanter says this will happen by 2025, which seems hasty to me, but he could be right. Tesla says its cars will have 90 percent self-driving capability by 2020, and Mercedes already offers so many driving aids the line between autonomous and manual operation is blurry. My own Ford C-Max offered the option of self-parking for parallel spaces, which no self-respecting native San Franciscan would ever want. In San Francisco, women deliver their babies right into a crib parked parallel between two other babies, usually on the first try unless their husbands are watching, in which case they blame him for “making me nervous.”

So what happens to motorcycles? Will we be ground into a powdery mush beneath the cute, grinning visages of Uber-labeled Google cars?

I don’t think so. I share Kanter’s chirpy optimism. The main enemy of motorcyclists, besides ourselves, of course, are careless, drunk, drugged, insane, asleep or just plain oblivious drivers. The requirements to get a driver’s license in most states are laughably lax, and once you take the test, you never have to take it again, even if it was in 1941. There might be a steep and painful learning curve, but once the software is debugged, robotic cars will rarely, if ever, cause injury to a human being.

Anyone who uses Microsoft products may find this hard to swallow, but it’s true. Robots don’t road rage, text and drive, fall asleep or binge drink and, hopefully, they won’t donk their 1993 Chevy Impalas and drive them down my street at 3 am blasting Big Sean’s “I Don’t F*%k With You.”

“Autonomous cars have no bad habits,” former Nevada DMV spokesman Tom Jacobs told me. Human drivers have “the illusion of attention – they’re looking for other cars, not motorcycles.” We’re less than one out of 100 vehicles, even in states with lots of motorcycles, and drivers don’t see what they don’t expect – look up the film The Invisible Gorilla if you want to know why.

Most importantly to motorcyclists, the sensors, software and other equipment in development are incredibly sensitive and designed to err on the side of caution – in the mind of a robot car, motorcycles will be a fast-moving bicyclist or pedestrian and will get treated with the respect and attention we deserve but seldom get. Contrast this with how we’re perceived by the average motorist – crazed daredevils who sort of deserve whatever happens to us. Robots don’t judge.

So I don’t think robot cars present a threat to us … directly. What I am worried about is the threat we represent to ourselves. Motor-vehicle death numbers will plummet as more and more autonomous vehicles get on the road (and it won’t just be passenger cars – you can imagine the advantage this will give to tractor-trailers, buses and other long-distance transportation modes) and at some point will be mostly motorcycle fatalities. That will present a plump and inviting target to do-good legislators and bureaucrats that could lead to motorcycling being severely restricted or banned. Yikes.

Hopefully, we’ll see motorcycle fatalities drop in the coming decades, helped by better equipment, better training, shrinking numbers of riders and of course, the benevolence of our new robot overlords. Hopefully, the numbers will get low enough that our presence will be tolerated. Like it or not, our privilege to ride will always be controlled by the non-riding majority we share the roads with.

I imagine I’ll be standing in the checkout line at a grocery store sometime in 2035, holding my Arai nano-helmet ($14,399) and wearing my Aerostich reactive-armored suit ($27,450), while the other people in line give me the hairy eyeball. But the middle-aged woman in front of me, hovercart filled with squirming kids and groceries, will chat me up. “What do you ride?” she’ll ask, and I’ll tell her about my 10-year-old salvage-title Harley Livewire. “Oh! A Harley! My uncle had one of those. He used to give me rides when I was a little girl. I can’t imagine driving myself around. I wish I had the nerve to do that.”

Then again, maybe things won’t change that much.

Gabe Ets-Hokin is a visiting scholar at the Bulgarian Institute for Pirogis and Draft Beer and author of the upcoming novel Girl with the Penguin Tattoo.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

Gabe, nicely done, as usual. Personally, I think I'd prefer a riderless car to an absent-minded driver who doesn't use his/her turn signals and is busy doing something else other than driving the car. I'm with the Colonel.

Distracted

driving is the #1 killer of motorcyclists and the #1 distraction is

cellphones. This would eliminate those deadly distractions. Maybe

mandate their use for drivers convicted of distracted driving as an

incentive to pay attention when you are operating a deadly 2-ton piece of heavy equipment.

Like · Reply · 4 mins