Higdon in South America: Part 11

March 2, 2018

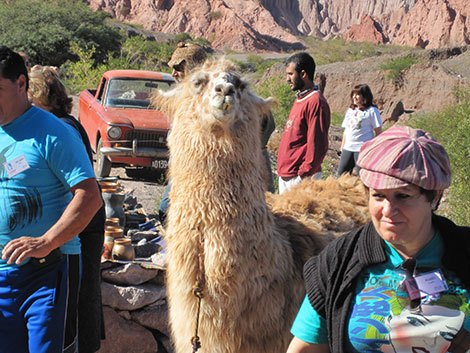

Salta, Argentina

Like most advanced, caring, and post-industrial countries, Bolivia has taken steps to ensure that its children are protected from the ravages of unfair labor practices. OK, your scribe was just having some fun there, since you know as well as I that every word in that first sentence is (with apologies to Mary McCarthy) a lie, including “and” and “the.” Nick was telling me at breakfast the other day what his tour of the mine at Cerro Rico had been like. “If I had known . . .” I interrupted him. “Stop,” I said. “I knew what it would be like: A dust-choked, strangulating hell at 14,000 feet where you’d sell your mother to a Portuguese white slave ring to escape from the place 15 minutes into a two-hour tour. How could you not know that?”

“Oh,” he said, “it was worse than that.”

He described it as “harrowing.” The word “claustrophobic” also came into play, as it does with many stories set in caves. The workers there, all young because the older ones have died off, need to load ten tons of ore each shift into large, rolling carts. Make your quota and you take home 150 Bolivianos, just under $22. Miss your mark? Try again tomorrow, Juan, but today your 12 hours of breathing toxic dust has netted you nothing.

The minimum age is 14, but everyone knows there are ten year-olds burrowing away like moles in that hill. Their mouths are so jammed with coca leaves they look like they’re trying to eat four golf balls. It alleviates hunger and increases energy, they say. They also say that on the Big Rock Candy Mountain the hens lay soft-boiled eggs. The few leaves I sucked on in Quito didn’t do much except get me on a DEA known user list.

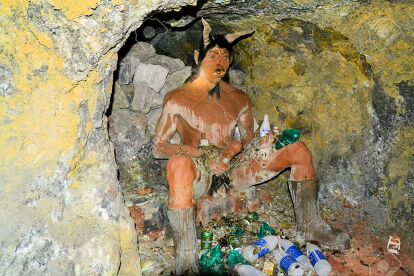

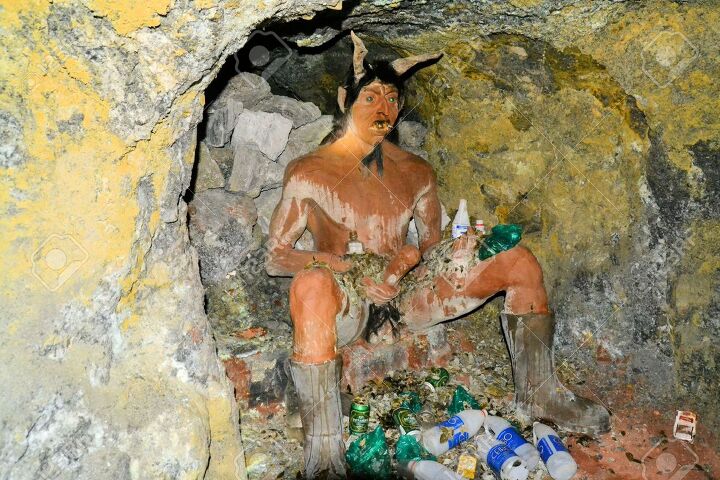

Nick was about ready to make a few dynamite holes in the damned place just to get some uncontaminated air when the guide said that there was one last station on the cross to visit: the God of the Mountain. I perked up. “Really? I wouldn’t mind that part of the tour. I’ve got a few things I’d like to mention to that Guy myself,” I said, perhaps a little too warmly. The guide noted that it would require traversing a path of about 50 yards on hands and knees, at which point Nick naturally offered an objection. It went nowhere. The guide explained that it was the only way out.

With all due respect to the panoply of deities, I’ve seen Nick’s photos of the God of the Mountain and I must say that this One’s sculptor is no threat to Michelangelo. It’s a kind of ribbon-covered mud pie in a more or less human form with a gaping maw into which worshippers have placed half-lit cigarettes and a genital package that appears to be more threatening than useful. I wasn’t comfortable that Mud Man would hear my prayers about the improvement of working conditions at Cerro Rico. No, for that I’m afraid I’d Better Call Saul.

* * * * * * * * * *

When we left the salt flats five days ago and headed south to Uyuni, we turned to the left in the middle of town and proceeded northeast to Potosí. Had we continued straight south, however, in another 75 miles we’d have come to San Vicente. You have heard of this village, even if you don’t know it. Hollywood has guaranteed it.

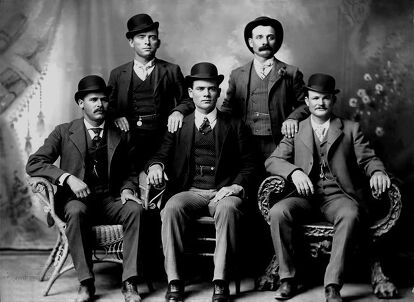

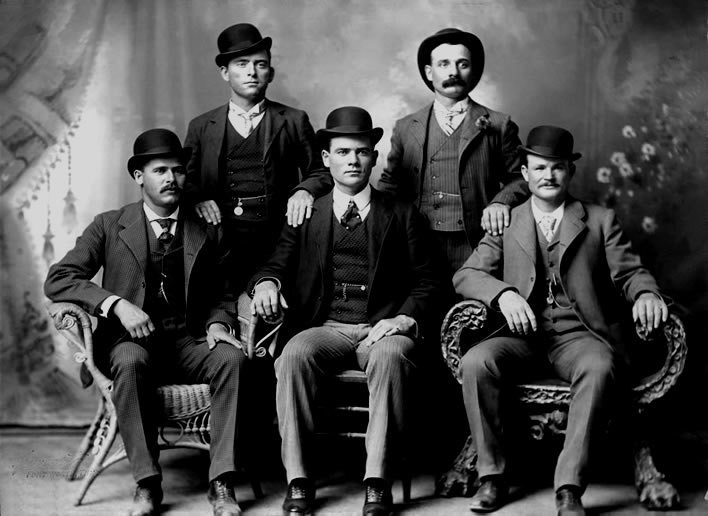

In 1901 after a remarkably successful ten-year career of robbing trains and banks in Montana, Wyoming, and Utah, Robert Parker and Harry Longabaugh decided that they would retire to Argentina and become gentlemen farmers. They were joined by Longabaugh’s girlfriend, Etta Place. The Pinkerton Detective Agency had been after them and their gang with every bit of the enthusiasm they’d earlier used to track down Frank and Jesse James. If you were west of the Mississippi at the beginning of the 20th century, you’d heard of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

For a while they appear to have kept their noses clean but in 1905 they robbed a bank in Patagonia of $100,000. They hit another at the end of the year west of Buenos Aires and escaped into Chile. In 1906 Etta Place, tired of running, decided to retreat to the United States. Longabaugh accompanied her, then returned to Bolivia, where Cassidy had a job working as a guard for one of the silver mines. Things remained quiet until early November, 1908, when two Americans heisted a silver mine payroll near San Vicente and stole a pack mule. The animal, worth nothing, bore the mining company’s brand.

They stayed the night of November 3 at a small boarding house in San Vicente. The owner, suspicious of the pair, found the mule’s brand and notified a local Bolivian cavalry unit. By nightfall the house was surrounded. When soldiers attempted to close in, one was killed and another wounded. A deadly firefight ensued. After midnight a man’s screams were heard in the house. Two pistol shots followed. At dawn the soldiers entered the house, finding both men shot to death in an apparent murder-suicide. Both had been bleeding out from dozens of bullet wounds. They could not otherwise be identified.

Were they the Dynamic Duo? Of course. Can we prove it? Of course not, though television crews with DNA experts have tried their best to do just that. But what mystifies me about these two in the end is what in the world were they thinking, pulling a robbery like that in an utterly desolate area? They stood a foot taller than anyone within a radius of 200 miles. Their accents would’ve give them away instantly. They could not have looked more like gringos had they been wearing Snow White and Cinderella masks.

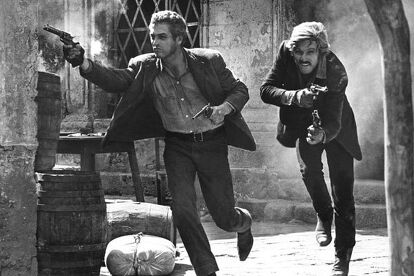

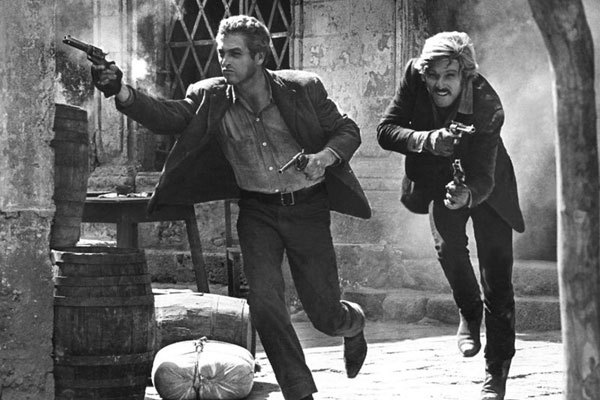

Sixty years after their unnoticed deaths, director George Roy Hill released his film version of the pair’s exploits, thus guaranteeing Parker and Longabaugh eternal celebrity. Though history has been kinder to the movie than critics were at the time, nothing for me can ever excuse Hill’s ending: His stars, Newman and Redford, burst from the boarding house in broad daylight with four guns blazing away and then . . . freeze the frame and turn it into a lobby poster. Sure, as if they might escape to star in a sequel.

The truth was far more horrific. They sat in that dark, miserable house, dying of arterial blood loss. For almost half their lives they had been inseparable friends, as lucky as anyone has ever been. Now one would have to shoot the other through the forehead, then turn the pistol to his own temple. How did it come to be called that, I wonder.

https://spotwalla.com/tripViewer.php?id=177dc5a62c0d1d6a1c&hoursPast=0&showAll=yes

More by Robert Higdon

Comments

Join the conversation

By now I've gotten the message this is a one-way conversation, so I won't appeal to you for some coverage of how the riders and their bikes are doing. I will just say this is a really well-written piece that had me feeling I was right there in that nearly airless dusty old dangerpit of a mine. Or awaiting a glamourless death with Butch and Sundance. Bravo.