Head Shake - Wins and Loss

I find myself sitting up at 2:30 in the morning sipping a cup a coffee and just letting my mind wander. This has become a pretty common occurrence here lately. I lost somebody I was very close to over the holidays, and it really put a damper on the, “Ho, ho, ho” aspect of the holiday season. And so I sip coffee at o’dark-thirty in a quiet house, on a quiet bay, and let my mind wander, looking for good and some sense of order in the dark.

The mind is a funny thing – mine is anyway – it looks for places to run to, places that make sense, familiar ground. Sometimes you kick it over and it runs fine, other times it just starts of its own accord, waking you at 2:30 a.m. and running backwards like an RD350 with a mind of its own, doing two-stroke things. I try to put things in context, my mind wanders to racing, and how racing taught me how to lose. A wandering mind in the middle of the night. It wanders to Ricky Graham.

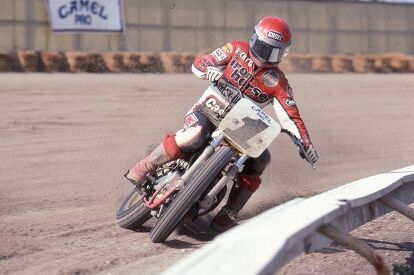

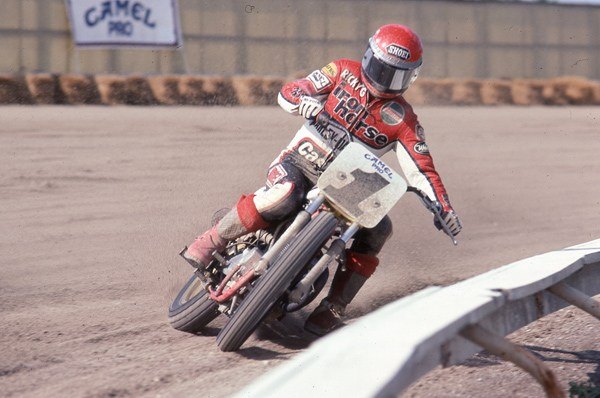

I thought back to the first time I saw Ricky on the track back in 1982 at the Louisville Half-Mile, leaving a plume of dust from his Harley flat-track racer on a picture-perfect day. I thought about how just two short years later Ricky changed the complexion of flat-track racing by winning Honda’s first AMA Grand National Championship. I thought back to his miraculous comeback in ’93, a year in which he was essentially unbeatable, setting records on his way to another AMA Grand National Championship, again on a Honda in a pack of Harleys.

Ricky excelled at the unlikely, on an unlikely machine, under unlikely circumstances. Anybody who has ever been an underdog, or been beat up yet come back and won on their own terms, has to appreciate the story that Ricky Graham left us. I thought about the tragic way he died, how loved he was by so many, and how many lives he had touched. I wondered how long it had been now, so I looked it up: January 22, 1998, that was the date of his death. That gave me pause.

As I sit here typing this right now; it is January 22, 2015, in the middle of the night. Like I said, the mind is a funny thing, and sometimes it runs backwards. In this instance, precisely 17 years to the day backwards.

I once lived in Guston, Kentucky, in a farmhouse in the middle of nowhere. I was in love with two machines and one girl: an M-1 Abrams Main Battle Tank, a 1982 Honda 750, and Wife Number 1. When I wasn’t on the tank, I was on the bike, and when I wasn’t on either of them, I was on the… ahem… I was bothering the wife (ver. 1.0). The only other place I could be found was at the Honda-Suzuki shop in Radcliff, Kentucky, bench racing with the parts guy which I could do for hours, or pestering the owner about who exactly had painted his Suzuki as I was looking for somebody to lay paint on my Honda. They were great guys down there.

The shop owner walked through the parts department one Saturday morning and dropped off an envelope, my parts bud picked it up and thumbed through the contents. He glanced up at me like he suddenly had an idea and asked me, “Hey, have you ever been to a flat-track race?” I sheepishly admitted I had not. I had seen plenty of road racing, but flat track to me was the sport of the Midwest – it was a heartland tradition of fairgrounds and horse tracks, and truth be told, TV just never did it justice. It still doesn’t. What I had seen of it on the tube seemed rather boring. I didn’t launch into that soliloquy though, I just kept it simple, I answered, “No.”

“Well here, we’ve been comped tickets to the AMA Grand National race up in Louisville, take these two tickets, take the wife, and you know that horse track where they run the trotters up there? That’s the place. You will love it. Oh, and this year there is a Honda in the field. This ought to be a good show. It’s on the house.”

I thought about that, a Honda. I knew enough to know that Harley-Davidson ruled the dirt ovals, they had for decades. A Honda and flat-track racing, what in the world? Harley owns flat-track racing. I snatched those tickets up and thanked him, hell, I was happy just to have a change in the routine, and I knew Wife Number 1 would be ecstatic to go to anything: the base bowling alley, a pig scalding, a bris, anything to break the monotony of life on that farm in the middle of nowhere.

And so we went on a beautiful June day. I had had days to think about it and I was pumped – a Honda racing dirt track, I wanted so bad to see this. I had played it out in my head – sure Harley owned the dirt track but who had really challenged them as of late? The sight of a lone red, white and blue machine flying around a half mile oval with a pack of Harleys thundering away in pursuit, just the idea of it. What if. Maybe the game was changing, and maybe we would watch it change today.

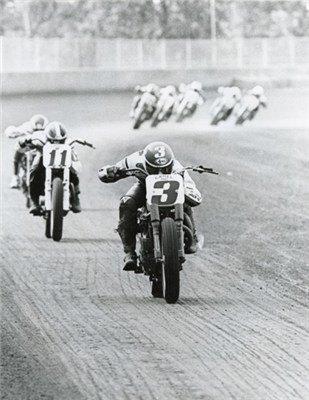

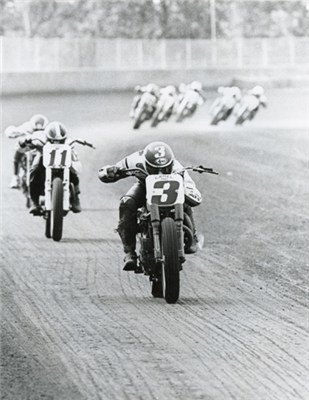

It was a perfect day, one of those robin-egg blue, low humidity, puffy cloud, early summer Kentucky days that make you forget the months of mud and ice in the field and your tank with the AWOL heater. We had gotten to Louisville Downs early, and we could hear the bikes starting up. The same pre-race routine observed at tracks everywhere no matter the composition of the track surface; dirt, asphalt, ice, it makes no difference – high compression engines starting, running, crew chiefs blipping throttles, and just as suddenly shutting down. Half-mile bikes thunder, the exhaust note thuds off the grandstands, you don’t hear them so much as you feel them in your gut.

There is something primeval and fearsome about mile and half-mile dirt track racers. The road race bikes I was used to – high revving inline-Fours of the era – sound like GP cars. Dirt track bikes sound like the U.S. 8th Air Force on their way to Schweinfurt circa 1943; all thunder and malevolence. If you don’t look too closely, road racing from a distance looks like a high speed choreographed dance; dirt track racing is a rolling bar fight. The grandstands vibrate with an overwhelming percussion that suggests something very serious is about to occur.

We went in and grabbed some seats. I hit the concession stand and started holding forth on any number of tedious things concerning Honda versus Harleys, David versus Goliath, jabbing my index finger in various directions as Wife Number 1 tried to act as though she was actually interested. The bikes mercifully took to the track, the roar drowned out my droning, and both Wife Number 1 and I sat; listening, feeling, and hoping that despite all odds the red, white, and blue bike might show the Harleys something.

As it was that day, the Honda did. Scott Pearson rode Honda’s HRC-built NS to Big Red’s first dirt track AMA Grand National win. Just two years later a second-generation Honda, the Honda RS750, would be piloted by Ricky Graham to Ricky’s second AMA Grand National Championship, and Honda’s first. The fairgrounds and the horse tracks were no longer the sole domain of the Bar and Shield, the RS and Ricky now owned the top of the podium. The game had changed.

Ricky Graham and that bike could make the impossible possible. In his comeback year in 1993, he set two remarkable records – he ran off six AMA Grand National victories in a row, and tallied up 12 Grand National wins for the season. He was named AMA Athlete of the Year. He was at once bigger than life, the kind of story that Hollywood makes movies out of, the giant slayer; and at the same time so human, warts and all, plagued by devils that haunt many souls down here trying to figure out what it all means, trying to live our lives, being human.

Ricky Graham died in a house fire in his home in California, January 22, 1998. And I sit here in the middle of a quiet night, precisely 17 years later thinking about him and how remarkable he was.

Ride hard, race to the checker, ride every lap like it’s your last, and enjoy every one.

For Paul Francis Kallfelz, Jr., he lived his credo, always faithful. Godspeed.

About the Author: Chris Kallfelz is an orphaned Irish Catholic German Jew from a broken home with distinctly Buddhist tendencies. He hasn’t got the sense God gave seafood. Nice women seem to like him on occasion, for which he is eternally thankful, and he wrecks cars, badly, which is why bikes make sense. He doesn’t wreck bikes, unless they are on a track in closed course competition, and then all bets are off. He can hold a reasonable dinner conversation, eats with his mouth closed, and quotes Blaise Pascal when he’s not trying to high-side something for a five-dollar trophy. He’s been educated everywhere, and can ride bikes, commercial airliners and main battle tanks.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

Our loved ones live on in our hearts. Thanks for the column.

This is the kind of writing that makes me sad you live across the country from me. SOMEBODY DESERVES A HUG!!!