The Life Electric: Next-Gen Hot Rodding + Video

The future of going faster starts here

Hot rodding’s history is filled with speed seekers that have gasoline running through their veins. But now there’s a new dawn in the age to go faster and Harlan Flagg, Brandon Nozaki-Miller and Jeff Clark are pioneering the way. The technology they’re working with might be different than that used by speed seekers before them, but the proving grounds remain the same. Competition improves the breed, and that’s the path Clark, Nozaki-Miller and Flagg have embarked on, pioneering the next chapter in hot-rodding – the electric motorcycle. Their challenge: the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

Brandon Nozaki-Miller’s dirty ginger hair is long and flowing, his normally scruffy beard is trimmed for once. If you stuck a Great Dane by his side you could make a strong argument that Nozaki-Miller is a doppelganger for Shaggy from the Scooby Doo cartoons. In fact, he can be rather aloof like Shaggy, too, but that’s where the similarities end. By day, Brandon is on the cutting edge of technology that can advance humankind, working with a team of developers at Second Sight Medical Products to create a bionic eye that would allow the blind to see again.

He’s extremely proud of the work being done at Second Sight, but Brandon’s a racer at heart. When he’s not modifying the human body, every other moment of the day Nozaki-Miller takes pride in calling himself an R&D test rider, software developer and racer for Harlan Flagg and the Hollywood Electrics Racing team.

Flagg, meanwhile, is an easily recognizable figure in the e-bike world. The electrical engineer and owner of Hollywood Electrics can usually be seen wearing a moto-themed t-shirt, black jeans, and his faithful black boots that have seen more than their share of resoles. Flagg is a rarity considering his West L.A. digs; he’s an unassuming figure in the heart of a town known for its vanity.

The duo’s third member, mechanical engineer Jeff Clark, can be mistaken for a fraternity brother in some circles, with beer in hand and adventure on the mind, but once he puts the helmet on he’s all business. Together they’ve taken on the role of making Zero Motorcycles circulate around a track faster than ever intended.

“The standard production Zeros off the showroom floor make great streetbikes,” says Flagg. “But we’re gearheads at heart and modifying is what we like to do. We wanted to see how much further we could take them.”

If you think about it, Flagg, Nozaki-Miller, Clark and those like them are reminiscent of hot-rodders of yesteryear. The early history of hot rodding involves taking what were essentially gasoline-powered grocery getters and extracting performance the engineers back in Detroit never dreamed of. Only now replace Detroit with Santa Cruz, California, and replace grocery getter with electric commuter motorcycle, and you have the canvas the e-bike tuning world is using to paint their masterpiece.

Humble Beginnings

For Flagg and Clark, their stories leading up to Pikes Peak are rather conventional. Both grew up gearheads with a fondness for modifying vehicles. Harlan once converted a BMW (car, not motorcycle) to electric power with his father and made extra cash working on British motorcycles while earning his electrical engineering degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

Clark, meanwhile, grew up in a small town in Colorado, free to roam on two wheels and four, riding anything he could when he was little and eventually graduating to big bikes as an adult. He moved from dirt bikes to sportbikes in his early 20s, but not before helping pre-run the Baja 500 and Baja 1000 for a race team who needed the help. His first sportbike was a Honda RC51, then an Aprilia Mille after the Honda was stolen. Trackdays led to track schools, and the urge to compete was born. In 2013, after hearing that Flagg needed a sixth bike and rider to create a new class at Pikes Peak, Clark purchased a Zero FX and sealed the deal.

Miller’s road to Pikes Peak is by far more unique than the others. In fact, Nozaki-Miller only started riding motorcycles in 2011, having never touched a motorcycle before in his life, gas or electric. Upon moving to Los Angeles in 2010, a two-hour commute to travel 12 miles to work had him looking for a better option than his car. Two wheels proved to be the answer, starting with a cheap Chinese electric scooter.

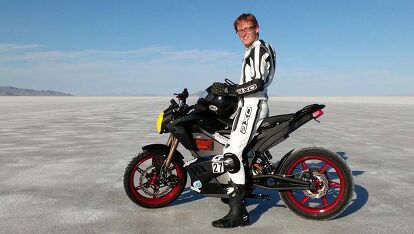

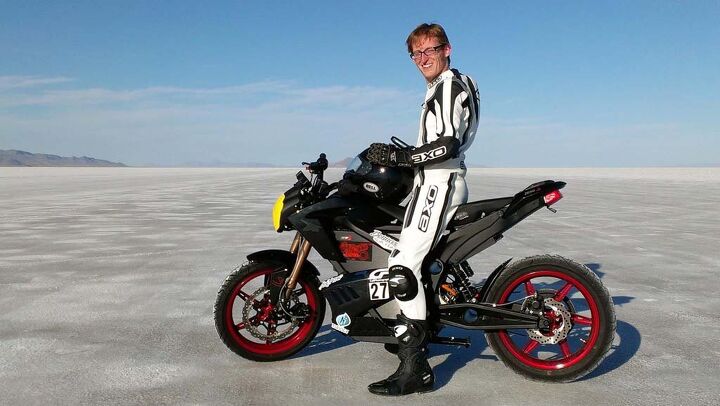

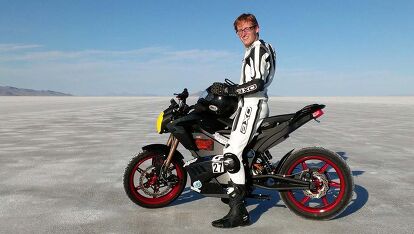

What was supposed to be a commuting machine ignited the need for speed in Nozaki-Miller, and attempts to make that scooter go faster eventually brought him to Flagg, who ultimately convinced Nozaki-Miller to purchase a Zero S. He got his motorcycle endorsement on it, and later his racing license, too. To this day he still hasn’t ridden a motorcycle with an internal-combustion engine. The S proved to be just the vehicle Brandon was looking for to cut short his commute time. Later, a day browsing the internet revealed the land-speed-record for a production electric motorcycle was a mere 68 miles per hour. That’s when it hit him.

“Holy crap, I break the land-speed record on my commute to work every day!” said Brandon.

The wheels were set in motion. The following year, 2012, Brandon upgraded to the then-new Zero S, and with Harlan’s help, Nozaki-Miller destroyed the 68-mph record, breaking the ton (100 mph) en route to a 103-mph kilometer and 102-mph mile in the FIM 150kg class.

Hot Rodding

Sometimes, making a Zero go faster really is as simple as replacing a part. Take for instance the 660-amp motor controller currently used in the Zero SR. Flagg and the Hollywood Electrics Racing team had been using that controller since 2012 in the then-flagship Zero S. “This gave us an extra 20% more power and roughly 34% more torque,” says Flagg. The performance advantage was so significant Harlan used the larger controller again the following year, and by 2014, Zero caught on and offered the 660-amp controller as standard in what we now know as the Zero SR.

But when it comes to pushing the limits of performance, the hot-rodding spirit is to dig inside the machine to see what can be made better. With hundreds of moving parts that all work in harmony to produce power, “It really is quite amazing the internal combustion engine works as well as it does,” says Brandon. Harlan then interjects and reminds his partner that the internal-combustion engine has over a century’s worth of development into it. In contrast, electric propulsion is relatively new, “with only two moving parts – the bearings in the motor” says Flagg. “There’s no brushes to worry about, and especially nothing like valves or clutches that can fail.” The stock system is so robust and simple, when it comes to upping the performance on an electric, two key areas are the focus: reducing heat to the air-cooled motor and maximizing battery discharge.

Battery discharge is a funny thing. For a road-going electric motorcycle, extending battery life (or range) as long as possible is a key goal to meet. Clearly, nobody wants to be stuck somewhere because of a dead battery. The standard Zeros have been making huge strides in regards to range, to the point that many adopters aren’t fraught with range anxiety anymore. However, the distances covered in racing are usually much shorter than the mileage one covers in their commute, so the goal is to use up as much energy as possible, as any extra charge left in the battery packs after a race means untapped performance that could have been used.

It’s here that the expertise of Harlan, Brandon and Jeff come into play, and the hot-rodding spirit comes alive. Instead of reaching for the wrenches, the team uses the wrench of the 21st century – the laptop. Tapping into the bike’s onboard diagnostics, they can see exactly how much energy is being used and also extrapolate which points on the course place the most strain on the system. From here, Harlan can manipulate the bike’s settings to best accommodate those needs and discharge maximum energy to the motor, and ultimately, put power to the ground.

But there’s a catch. “When I was riding the 2011 and the 2012 bike at the track,” Brandon recalls, “I was discharging so much power from the batteries to the motor that when I came in from a session the motor was so hot you could cook off it. I’d have distilled water set aside so I could pour it over the motor to cool it off before the next session.”

More power equals more heat, and heat is the enemy of performance. Early attempts to cool the motor varied widely. Ram-air devices were used, and even an experimental enclosed tray above the motor was fabricated to store ice. Another, simpler solution the team came up with was ventilating the motor itself by removing unnecessary plates within the motor housing, thus allowing more air to flow through.

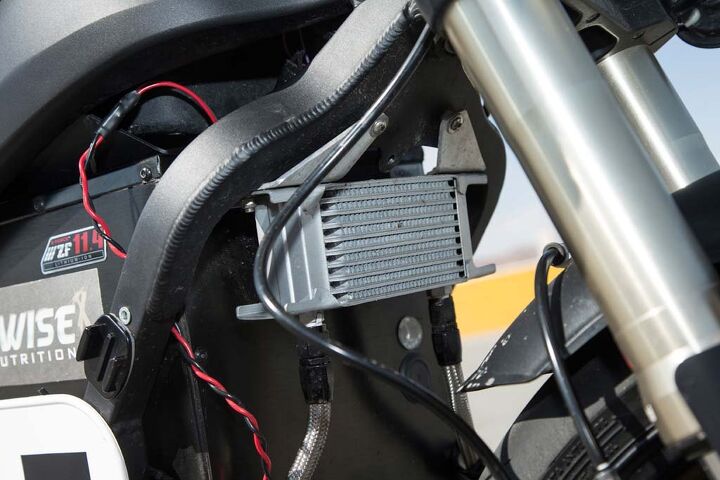

The most radical attempt to keep the motor cool, however, was devised between Clark and Flagg. Their plan was to take Nozaki-Miller’s idea of splashing distilled water over the motor one step further – the two were going to introduce Jeff’s Zero FX to liquid-cooling. Clark and Flagg developed a routing system within the motor to distribute liquid to keep things cool. Meanwhile, a radiator was installed just in front of the battery to cool the liquid, and an electric pump mounted below the battery box would force the liquid to flow.

“We got the system working fairly well, but there’s still areas to improve,” says Harlan, noting that different tracks place different strains on components, which require different cooling needs. The challenge then becomes figuring out the minimum amount of liquid necessary to cool the motor while creating the least amount of interference possible.

Whether it’s gas or electric, no other environment pushes machines to the max like a race track. It was decided then that, with Harlan running the show, Brandon and Jeff would participate in local rounds of the TTXGP, M1GP, and later the eMotoRacing series, using those races as opportunities to fine tune their ideas.

What they found out was that, as one component improved, weaknesses of others were highlighted even more. Changing springs and revalving the suspension internals became a necessity, as did converting to chain drive to provide more gearing options via different sprockets. Lastly, they also fabricated custom brackets to move the rearsets higher. Slowly but surely, the trio were living up to the hot-rod ethos and converting their Zeros from road-going motorcycles to track-focused racers.

Maybe most surprising to the team was the fact their home-brewed modifications were holding up remarkably well. Brandon, with his air-cooled motor, reported far less thermal cutback issues during testing thanks to the vent holes the team cut out, and Jeff reported even fewer thermal issues still.

The Peak

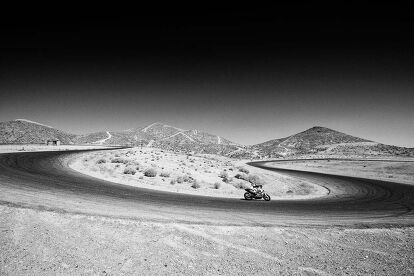

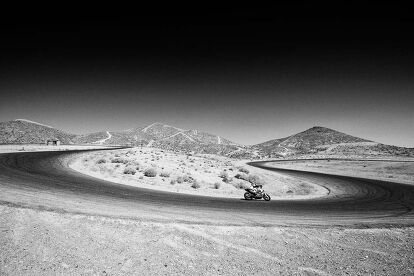

The point of all this fabricating, testing and tuning, of course, was for a singular purpose: Pikes Peak. The second-oldest motorsport event in the United States behind the Indianapolis 500, Pikes Peak spans nearly 13 miles, packs 156 turns, and raises in elevation 5,000 feet. It’s one of the most grueling tests for both rider and machine, and this is what makes it the most important event on the Hollywood Electrics Racing calendar.

Having first competed with a six-man team in 2013 on lightly modified Zero S and FX models, Harlan took the lessons learned that year and returned the following year only with Clark, aboard his winning FX from the year prior. Over the course of that year, the two adapted the first iteration of the liquid-cooling system, only to discover the bike was geared wrong for the mountain. “We had focused so much on one detail we neglected another,” admits Harlan.

With those lessons learned from four years of modifying Zeros, the Hollywood Electrics Racing team returned to Pikes Peak in 2015 with a three-man team of Nozaki-Miller, Clark and Nathan Barker. This time all were on Zero SR models in various states of tune. Barker rode a mostly stock SR, Nozaki-Miller’s ran the air-cooled motor with suspension mods, while Clark’s SR also featured suspension mods but was equipped with the latest version of the liquid-cooling system. All three crossed the checkered flag reporting no issues. Clark placed highest of the trio, his 12:06.3 time good enough for 30th out of 62 motorcycle competitors.

“I’m really happy placing mid-pack against the other [gas] bikes,” said Flagg. “We’re relatively new to the game and we’re already pushing the limits of what’s essentially a streetbike high enough to place mid-pack at Pikes Peak. That’s pretty good.”

What does the future hold for the next generation of e-bike hot rodders? Considering the two fastest cars up Pikes Peak in 2015 were both electric, and there are four-wheel drive electric supercars with torque-vectoring technology, that’s a prospect Harlan’s excited about. “Maybe we don’t have the imaginations yet to see what this means.”

Imagine that. Options so varied, so diverse, the possibilities are limitless. The future of hot-rodding looks bright.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

Very well done, Trizzle.

For anyone who's seriously considering a purchase, there's a groupbuy happening now for the 2015 Zero SR that includes an $800 in store credit at Hollywood Electrics. More info: https://groupgets.com/campa...