Winning The Peace

A Memorial Day Lunch Ride to Remember

The day began like all summer days do in Japan, with the incessant shrieking of cicadas and rapidly building heat. At just 10:00 AM, the atmosphere was already a thick, steamy mess and although I expected the transition as I stepped from the air conditioned comfort of my apartment, I still paused for a moment in that same way a person naturally does when they step into a shower that is set just a little too hot. Even at this early hour it was obvious that it was going to be another scorcher and I toyed briefly with the idea of abandoning my plans and returning to the comfort of the sofa. But my ’91 GSX-R 1100 had sat unused for too long and the truth was I felt guilty about neglecting it.

I had purchased the big Suzuki with the full intention of riding it as much as possible, but marital bliss had intervened and I found myself using it less and less. Still, I reasoned, a person has to make time for the important things and so, on this particular morning, I decided that I would ride the motorcycle across Osaka to the recently constructed Costco for no better reason than to buy a hot dog. It would be a welcome bit of solitude; an all-American day in a foreign land.

Traffic was moderate and, despite the Suzuki’s size, I pushed past cars whenever I could, splitting lanes as necessary but never really unleashing its full power. At some point in the past, a previous owner had made some serious modifications to the bike, making it truly a wickedly fast motorcycle. But the modifications, which probably worked well on the track, were less than suitable for city streets. Riding the bike on public roads required focus, and that effort, combined with the heat of the day, took a lot of the fun out of the almost thirty minute trip. I arrived at the Costco tired and cranky.

For whatever reason, the line at the hotdog stand was huge. Hundreds of small dark haired women, many with children scuttling around their feet, waited patiently in long lines, each one taking a few extra moments to verify the complicated menu that listed so many odd, Western food options prior to placing their orders. The entire process took far too long and the excessive wait did little to mitigate my crankiness but I eventually found my way to the front of the line and placed an order.

Hot dogs and soda in hand, I turned towards the tables found myself facing a sea of sullen faced men. Although none of them had a scrap of food, they occupied virtually all of the tables and they gaped at me unrepentantly as they waited for their wives, who were lost somewhere in the mass of humanity lined up before the counter. There I stood, two dogs gripped in my right hand as it stuck through the chin bar of my full faced helmet, my leather riding jacket in the crook of my arm and my tank bag and a soda tenuously sharing the grip of my left and there was quite literally nowhere to sit. Suddenly my benign crankiness flashed into anger.

This was just so typical, I seethed. Like a well-practiced team, these men had rushed to the tables and staked-out their territory while their wives ordered and prepared the meals. Meanwhile, no one who actually had food would be allowed to sit. I stalked into their midst staring them down and forcing them to look away whenever they dared to glance in my direction. At last in the middle of this group I found a single empty table, with only a carefully folded jacket draped across one side of it. Frankly, I didn’t care anymore, chances are I would finish before the jacket‘s owner returned so I sat down and unloaded my food.

I had only taken my first bite when they arrived. An elderly man, perhaps in his 70s, his small, silver haired wife, their daughter and grandson approached the table furtively and made to take the coat away. In their hands they each had a plate of food and I could tell when I made eye contact that, like me, they knew there was nowhere else to sit. If it had been a man my own age, I probably wouldn’t have cared, but there was no way I could ask an old man, two women and a child to stand while I sat alone at a table, so I began to wrap my hotdog back up and rise. But the man waved me back into my seat and, after a word with his wife, they all sat down, the little man across from me, his wife to my right and the daughter across from her with their grandson on her lap.

I imagined what they must be thinking and my anger subsided. It was only mildly uncomfortable for us all and soon, as I eavesdropped, they were chatting away with one another about the most ordinary of subjects, carefully and politely avoiding the topic of the giant, unpleasant Western gorilla who had stolen their spot. I finished quickly, gathered my trash and made to leave when the old man spoke directly to me for the first time.

“Are you an American?” He asked in halting English.

I paused. It could be something of a loaded question, I knew, but I am what I am so I looked him in the eye and answered. “Yes.”

He waved me back into my seat and leaned in close across the table. “I speak English,” He told me in a quiet, almost furtive voice. “I worked for the American Navy in Yokosuka at the end of the war.” And then he told his story:

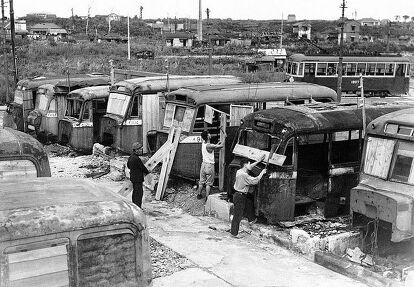

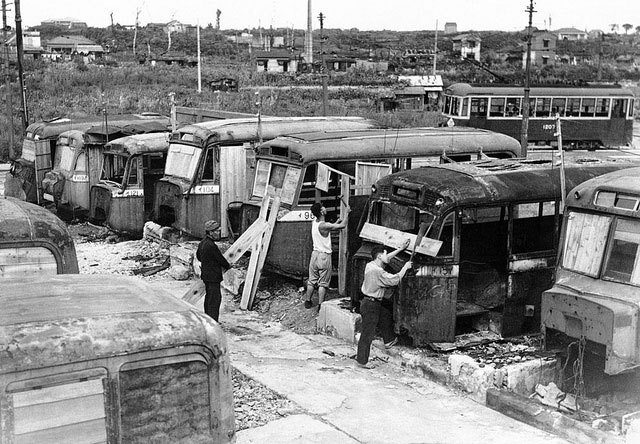

One day just before it was time to go home, an American sailor came into the hut where we gathered. He had a big shoulder of beef in his arms and he put it on the table in front of us. He told us, “Don’t anyone touch this! This base has a rat problem and we need to see if this shack has rats in it. I will leave this beef here and if it is gone in the morning I will know there are rats here and can call an exterminator.” Then he left.We thought he was crazy! We were starving and he was going to leave the meat for rats! When he left, we cut up the beef leg and took it home. We knew it was wrong, but our families were starving. We thought we would be punished but we had no choice.

The next day, the man came back as we were going home and instead of punishing us, he put another large piece of meat on the table. He told us, “There must be many rats in this building because in the morning I didn’t even find a single bone from the meat I left yesterday. I need to know how many rats are here, so I will leave this meat here as well and come back again tomorrow.” Naturally, we cut that meat up and took it home as well.

The man came every day for several months and we always laughed about how foolish he was. Today I am older and I understand what he was doing. That man had been told it was against the rules to give food to the Japanese, but he saw us starving and found a way to help us. He might have been arrested and punished for disobeying orders, but he put himself in grave peril in order to give us food. We laughed at him and I am sorry about that to this day.

The old man looked at me with tears in his eyes and, to the shock of his wife and daughter took me by the hand. “The Imperial military abused the Japanese people and they would have let us die for their glory. Our enemy came and saved us. I love America. I know it is the greatest country in the world. Thank you.”

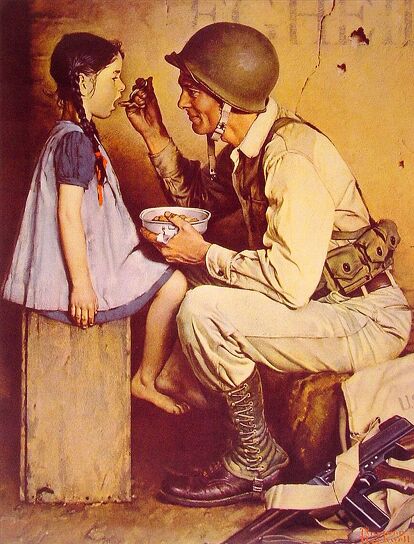

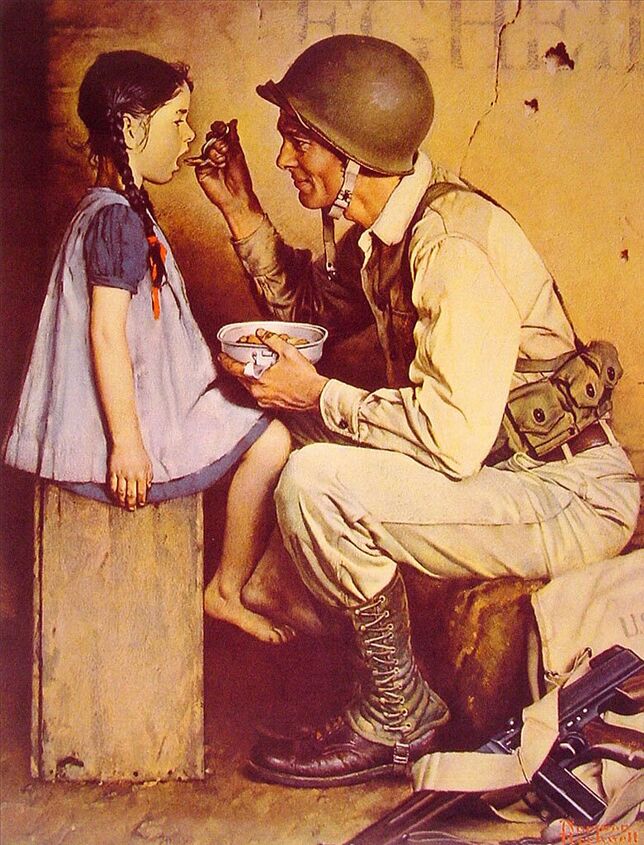

I can see that U.S. sailor in my mind’s eye now. He is typical of those we call the greatest generation, tall, hollow eyed and raw boned. He might be a farmer from the Kansas plains, his brown hair bleached blonde from long hours of hard work in the sun. He might be shorter, heavier, and a survivor of the hard streets of New York or some other crowded North Eastern city. He might be an American Indian from the Southwest plains whose family had been consigned to a life of poverty on an isolated reservation, or an African American who had gone into the service despite his own country’s lack of respect or concern for him and his family’s well-being.

Whoever he was, that sailor knew what suffering was when he saw it because he had lived it. He had felt the bite of hunger, seen the swollen bellies of his brothers and sisters and he knew, despite the fact that the people in whose faces he saw it reflected had recently been his country’s sworn enemy, that he could not let human suffering go unanswered. Instead, he chose to make a difference, and that choice echoes down through time to this very day.

On Monday, our country pauses to honor the men and women, our sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, mothers, fathers and grandparents who gave their lives to our nation’s service. We will remember their great deeds, the battles they fought and the obstacles they overcame. As we remember their struggle, it is all too easy to let slip away those other important things they did in all our names, all those times when they acted out of kindness and simple human compassion. We should seek to remember all those things as well, because it is through them that we won the peace.

To everyone who has ever served, thank you for your sacrifice, but thank you also for your humanity.

More by Thomas Kreutzer

Comments

Join the conversation

Perfect story for Memorial Day!

Fantastic story! Amazing things happen when we have the courage to actually talk to people. God bless that old Japanese man, and thank you for sharing that.