Riding the Hypercycle Vintage Racing XR69 Beast (and Other Classic Tales)

How to Embrace Becoming a VD (Vintage Dork)

So, I asked Mark Miller to whip up a few words about what it was like to ride the bike Carry Andrew built for Colin Edwards to ride at the big Australian Island Classic vintage thing earlier in the year; little did I know MM would knock it out of the park with this epic tale. Tales. Thank you, MM! (Check in mail.) – John Burns

On Carnies

Ask any group of aspiring roadracers from the late 1990s what their biggest fear was when arriving at the next championship circuit on the calendar, and I’ll bet you a large percentage of them would respond with the same answer; the fear of being stricken by VD. Or, Vintage Dorks.

Vintage Dorks, as many of us will recall, was that group of toothless nomads who would occasionally invade our oh-so-precious AMA paddocks and bless us with their excruciatingly loud straight pipes, poor carburetion, the smell of cabbage, and the ever obligatory parade lap upon which, by law, at least one of them had to leave a mile-long spooge of oil climaxed over our racing line, 10 minutes before start of the next televised event.

Remember?

Then track announcer Richard Chambers would follow up over the loudspeakers with the well-rehearsed, “Well folks, looks like there’s going to be a 30-minute delay…”

Richard, I could have told you this was going to happen last Thursday.

All kidding aside, and a swift fast-forward a couple decades; boy how times have changed.

On Time

Our dear friend, Time. Time has always been a fascinating thing to ponder. It can literally mean different things to different people, largely depending on their age. For a tiny baby, an additional 12 months of its life will double its total experience, so one year will seem like, well, a second lifetime. To a 50-year old, one year is 1/50th of their total exposure, so Christmas seems to come around like it was yesterday. And to someone turning 100, a 70-year old is just a baby who doesn’t know the first thing about growing old.

Back on topic, what fascinates me about classic motorcycles is how each additional model that rolls off the assembly line will remain forever fixed in time. The day a new bike is manufactured it becomes in that instant nothing short of a time capsule, a beautiful thing, really.

If you’ve ever wandered through a small legion of perfectly restored motorcycles, and from multiple decades, you can’t help but feeling you’ve revisited various states of technological advancements, as well. Also the desires of the importers from that given market at that time, and at a given price point and function. The customer’s demands, their fads or trends, even the styles or fashions of the day. You can deduce all of these things just by pondering a motorcycle.

But what powerful emotions might a ride on one these time machines give birth to. Or, rebirth to?

On The Next Generation

“Son, when I was a young whipper-snapper like you we raced Kawasaki ZX-7s. Do you know what those are, Billy?”

“No Grandpa. Don’t care.”

I think the first question that will always come to mind when an experienced rider is asked to ride a classic bike is, how did it, and therefore how does it, work now when ridden in anger?

One thing that should always be stated before discussing the impressions of racing modern top-shelf classic machinery is that advancements in tire performance could never fully give Modern Man an accurate impression of how the motorbikes from those thrilling days of yesteryear really worked, as even the simplest of AVON tires the size of your wrists are going to work better than the best Dunlops of the 1930s. Further, 18-inch Metzelers will run circles around the Goodyears of the 1970s. And finally, a brand new set of 17-in Pirelli Diablo Supercorsas made this month would thoroughly smoke any Michelin manufactured in 1993.

So, we’ve gotta keep this in mind before pontificating from a soapbox how brave the men were from this era or that, but our generation has been able to go even faster and faster and without crashing, etc. In many cases, even our track surfaces have improved. There, I said it.

Even so, let me spin you a little report about recently racing four once-unobtainable, but now unrepeatable, past superbikes.

On Holy Shit

Story one, I’m 47 years old now as of this writing, which means two things: One, I’m old. And two, I was in high school in the United States from 1984-1988, which were years that saw tremendous growth in the development of modern superbikes.

Recently gone were the wide chrome handlebars of Wes Cooley’s naked four-strokes. What those were replaced with was nothing short of the first generation of the Fred Merkel Honda VFR750F, Slingshot air-cooled GSX-Rs from Suzuki, FZs from Yamaha, and some ugly Ninja-pigs from Kawasaki which I have little memory of – no offense. But genuinely lightweight, nimble, aluminum-framed sport bikes with insanely grippy rubber. And these bikes were not only quick, but they turned and stopped like nothing else ever had up to this point.

It was the first time anyone could actually buy a full-fairing’d Grand Prix bike, but with mirrors and turn signals installed to make them street legal. And I’m sixteen at this time. Okay?

“I don’t have the $6000 with me right now… it’s close by.”

“In zee car.”

“No. Not in zee car, mang.”

Scarface (1983) movie quote, my bad.

Where was I? At the time, I was happy enough to just go to dealerships and sit on these incredible, space-age machines. And I did, often. It was a place to dream.

Twenty-seven years later, now a professional racer, I got an email from the organizers of the Isle of Man TT, which said they were trying to up the profile of their Classic TT event and wanted to know whether or not I’d like to be involved?

A team from the Netherlands had successfully secured full factory Yamaha backing to build a small battalion full of past-winning Yamaha race bikes, not for a museum, but with the specific intent to race them again. Several race bikes had just been assembled and now this official Yamaha Classic Racing Team (YCRT) wanted to enter a few of their bikes in the upcoming Classic TT, which was in August of 2013.

I naturally agreed (are you f’ing kidding me?) and you’ll never guess what they asked me to ride?

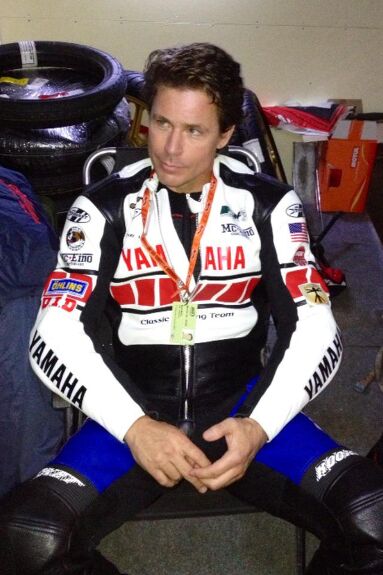

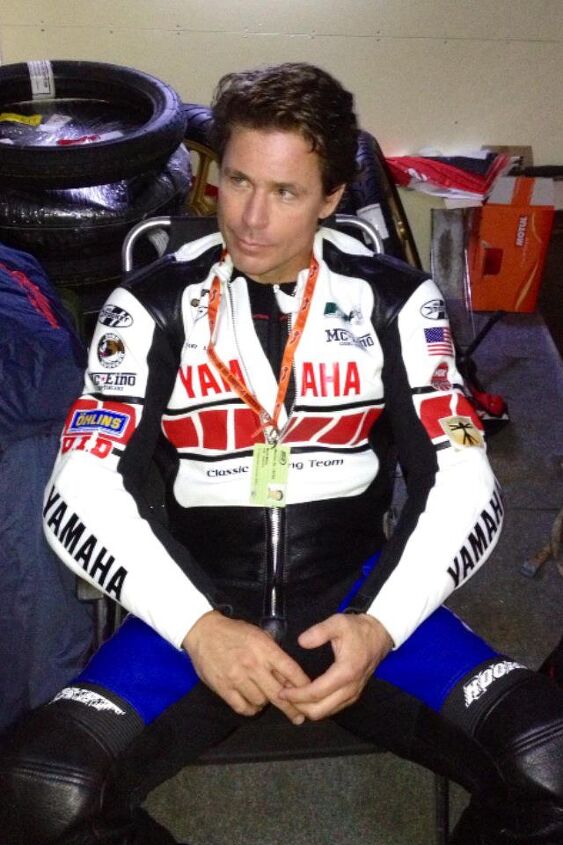

I show up to The TT Grandstands with a brand new set of custom Yamaha Classic Racing Team leathers, find this enormous YCRT circus tent erected there, introduce myself to the team principal, Ferry Brouwer – former World Grand Prix mechanic and then current importer of ARAI Helmets to Europe. Ferry pulls me over to one side of the tent and reveals to me that being American, I’d been chosen to race their fully-kitted, Factory Yamaha 1986 FZ750 Superbike, which was an exact near bolt-for-bolt replica of the FZ Eddie Lawson won the 1986 Daytona 200 on. And remember, I’m sixteen, er, forty-three at this time. Okay?

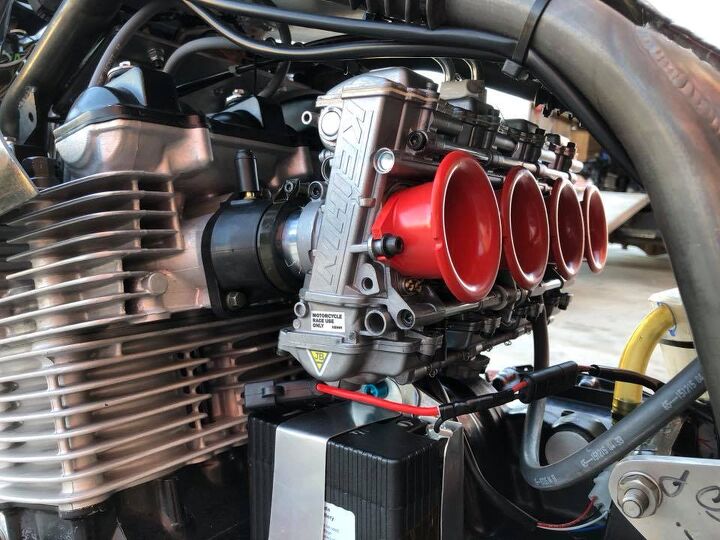

Ferry takes me on a tour around this meticulously prepared machine; legit thick glossy paint job, $35,000 kit carbs (of which five sets were made), factory triple clamps and fork tubes. Aluminum oversized radiator, dry clutch, 17″ magnesium wheels, modern Pirelli tires. Did I mention the dry clutch? Crazy cool stuff to behold here.

Then he leaned into me and whispered with his Dutch accent, “Mark, now please. You must listen. This is a collector’s item, and is largely irreplaceable. It is in many ways, priceless. Please, I beg you, do not hold back, but wring her fucking neck, ride her hard, pull her hair and make her scream again like she always loved to – but beat Team Classic Suzuki.”

This is how I remember the conversation going, anyway. Sorry Ferry.

But welcome to the “modern era” of Classic Racing!

In short, riding her was the best experience of my life to date. So stable, so fast. Throaty flat-slide carbs that rattled loud and wouldn’t idle. What can I say, she was amazing in the sack, I mean on the track. I fell in love.

There was probably a poster of her sister and Eddie Lawson up on the wall of the parts department back at the Yamaha dealership thirty years before when I’d go sit on a similar but brand new streetbike. Talk about a motorcycle being able to produce emotions from your past? Incredible.

We got 5th out of 65 starters in the 2013 Classic TT. I got beat by three 1200cc machines (Michael Dunlop won the race on his Team Classic Suzuki XR69 replica) and one other 750cc machine being a newer 1992 OW-01.

One additional note of fun: Legend has it that Shigeto Kitagawa, a chief member of the development team at Yamaha which oversaw the design of the OU28 (Japan version of the FZ, the OU45, or FZ750 Daytona, being an American exercise), was at the 2013 Classic TT for his retirement party. This after decades at Yamaha helping to design MotoGP Championship winning grand prix bikes for the likes of Valentino Rossi.

Kitagawa-san, I was told, enjoyed a quiet cry after seeing what was effectively his first baby girl being raced again, and doing so well. Aww.

After the race our proud lady was flown to Tokyo, murdered Manx bugs still splattered on her face and all, to be placed in a commercial museum where she stills chills out today. There’s also a framed results sheet beside her which the team asked me to sign. Sniff.

So! For story two, and two years later in 2015, a team from Finland asked if I’d like to race their fully-fitted 1991 Kawasaki ZX7-RR for that year’s Classic TT.

The funny thing about this was my very first real race bike was a 1991 Kawasaki ZX-7. Now, 24 years later, I’m being asked to race one again. Only, this was to be the special limited-edition version, with aluminum tank, flat-slide carburetors, and gearbox. I always wanted to ride one of these, but could never afford it back in the club race days.

We managed an 11th-place finish out of maybe 70 starters and found a mile-per-hour average just shy of 121. Not Hicky’s 135.4mph average TT record lap from last week (well done, old boy), but I was still pleased. Riding the 1991 Kawi chassis again was such ‘a trip’ because I instantly remembered the way she felt from when I raced one much like her when she was new. There was a distinct signature in how she turned and braked, and like an old habit, I just fell right back into it. It was a tangible memory, too, tactile. Very surreal, but very cool.

I could start to see how racing motorbikes from past eras can take on much more significance if you’ve shared some experiences with the same machine in your past. Maybe it was when you were a different person, or before a beloved family member had died. Maybe it was a time when your future looked much brighter. Powerful stuff, these classic bikes.

One thing that was apparent after riding a couple of the old 750s compared to today’s 230-hp superbikes, is today’s monsters are far less stable when ridden hard, even with their electronic aids. The fastest bikes today are just mental-fast accelerators, and can be downright violent when pushed. It’s kind of a different game completely, superbike to superbike. Which scheme do I prefer? Both, honestly.

Story three, only last year Mr. Carry Andrew of Hypercycle Suzuki fame, an absolute legend in his own right, invited me out for a makeshift reunion, exactly 20 years after I raced for Carry in the 1997 AMA/Pro 600 and 750 Supersport National Championships.

But instead of getting to be reunited with one of my old supersports, Carry was going to send me out on his precious full-kit Suzuki superbike. Please understand, this was basically the exact bike given to Mat Mladin to compete with, an again unobtainable piece of magic with $100,000 worth of kit parts that I was not privy to back in 1997, but which I would have killed for at the time. Now, I get to race one. Exhale.

Arrived at Willow Springs, threw a leg over, got the push and the bump start, and what a sound. So lean and crisp. I felt I was getting spoiled being around all these flat-slide carburetors again. You rotate the grip, it pulls a cable. The cable pulls a cam, and the bike mechanically receives fuel. A pristine fuel injection system just doesn’t feel the same, very detached suddenly, and until you go back and rotate the old school way, you forget. Ride a bike with big competitive flat-sides and you’ll soon not forget because they give you arm pump and fall on their faces if you don’t keep the rpm up.

We won our little club race, I didn’t crash Carry’s baby, and I just could not believe how well that little 1997 Suzuki GSX-R750 handled. What a great era the late 1990s were for American roadracing. This was my era. This turn around a fast circuit again on a chassis I was very familiar with, earning several AMA podiums on, nearly brought me to tears. These fucking bikes work.

So, there might be more to this classics revival than just simply a cheap way to go racing or an avenue for the obsessed among us that just love to restore stuff not only as a hobby, but in order to stay sane. I know some very intelligent people that restore old bikes to genuinely mint condition, then enter them in shows against other genuinely mint motorcycles. And the smiles these boys and girls get on their face when they win that tiny blue ribbon, holy shit, a whole lotta love there. On closer inspection, there is in fact more to this classics scene than just racing them.

But I do believe it’s the racing of classic motorcycles that’s been the largest force in driving a massive growth in this “renaissance.” I might be biased.

My fourth story is perhaps the most intriguing.

At the 2015 Classic TT I noticed a lot had changed in just the short period since we rode the FZ750 to fifth place. Most of the 1990-ish 750cc bikes were now punched out and stroked 850s. There were even more 1200s up front but now it was common to see, for example, a 160-hp Yamaha FJ1100-based engine, built with modern parts, slipped up inside a hand-welded tubular frame with bodywork and tank shaped like a “classic” Suzuki XR69.

Called by some, a BITSA – bits of everything – you can find R6 forks bolted to bikes with carbon kevlar bodywork, modern magnesium wheels, large modern Japanese flat-slides, and some permutation of APE or Brembo brakes that don’t appear in any old photos you might see from the era. In general, in 2015 the level-of-build in maybe the top twenty bikes had stepped up massively. It also seemed that most of the best TT riders had heard about the fun they were missing, which shortly thereafter found many of them aboard top-shelf classic rides. This stiffer competition has, as it always does, bred the classics racebike’s “progress” exponentially forward.

Even without being armed with the latest (digital) technologies of today, many of the top classic teams at present are taking their racing to a very advanced level. This naturally means a bit of serious money has also begun to flow into these efforts. Bigger money has always driven the highest levels of racing and I reckon always will.

Not everyone would agree to this state of affairs being allowed, and you might be hard-pressed to find anyone sleeping down in the lower paddocks at the Classic TT who’d be pleased to see the wealthiest teams among us (now some even with manufacturing backing) to continue to push out those who could almost certainly claim their birthright to this genre of racing.

Is this is a bad thing? I personally don’t believe so.

On a slightly brighter side, there still seem to be many opportunities around the world to race classic bikes at all levels and budgets. And frankly, no form of racing, and I think uniquely so, could be considered less fun or more moral. It’s all fun. One reason being, there’s never a sure winner before the green flag drops, that’s why we run the race.

On Progress

I just recently got to ride one of these “Suzuki XR69s,” one of these BITSA bikes… Carry Andrew, the one and same, invited me to test his brand new XR69 hybrid prior to Colin Edwards taking the same bike to Phillip Island for the 25th Anniversary Island Classic.

Beautiful bike. A “classic”, but built not so much as a restored original, but a from-the-ground-up race machine. This thing was built for one thing, and that’s speed. After some tweaking, we were up and running, and holy shit did this thing rip. It wheelied so violently out of the pits I nearly looped it. It only then occurred to me that this doesn’t have a six speed close-ratio gearbox with a tall first gear. It’s a 1984 FJ1100 at heart, with a five-speed gearbox and short first gear, transplanted into a handbuilt grand prix chassis. Hell yeah.

She wheelies in every gear including fifth, she carves the corners like a dream, she runs out of straight away before she runs out of motor. I mean, what the heck else do you need? Super fun.

We had so much fun, Carry invited me back out to race his XR69 in an “exhibition” event held during an American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) weekend, again at Willow Springs, in Southern California.

Just before the exhibition race, the one thing I couldn’t believe is how nervous I was. This simple, short circuit sprint, and I’m seriously feeling the butterflies. This brought it all home as to why we race classics or anything for that matter. You run the race, you get the result. That you on that day, that is your worth. So very cool, and unusual.

I was happy I didn’t cock up the race, I didn’t bend Carry’s new bike, I didn’t blow her up. And I felt something when taking the checkered flag. Then in the car driving away from the circuit. Then finally again when I walked in the front door of my house, and smelled my most familiar surroundings. A sense of accomplishment, a sense of purpose, and I guess, a sense of worth. Isn’t racing grand? So simple.

Back at the Island Classic in Australia, Colin held his own on Carry’s new bike against the likes of Troy Bayliss, Troy Corser, TT Racer Davo Johnson, and even Jason Pridmore. The racing was hotly contested, super close, fast AF, and serious.

At the last IoM Classic TT, Michael Dunlop won the race on his official Team Classic Suzuki entry, nearly eclipsing 130mph average! And what a beautiful machine, that is.

Funny how even a pursuit to replicate the past, now, has kicked off an entirely new arms race between today’s top factions, who very probably resemble those who enjoyed the fierce competition back then. Only, they were using the real missiles of the day, on their tires of the day, whereas our leaders slug it out in our current era riding armory only loosely based on the originals. We motorcycle people can bastardize anything, ha ha. I love it.

You always want better kit, no matter what.

On The Future

At the further most extreme other end of the classic racing spectrum, I’ve kind of been uniquely privy to some of the most state-of-the-art futuristic electric-bike racing. Talk about a wide range of technologies to accomplish the same goal, which is: the least amount of machine to propel a human body as fast as possible, controllably and reliably, across the surface of this planet.

Two wheels, a set of handlebars, and a steep hill. Go. Oh, you wanna race?

In conclusion, there is currently a crusade to see these highly tuned ultimate classic beasts like Carry’s or Team Classic Suzuki’s XR69s raced in the near future in California, then across the United States. A few of us will be at Laguna Seca next weekend for the World Superbike and MotoAmerica event, June 22-24, 2018, to put Carry’s terrific Hypercycle XR69 out on display and I’m told I might even be allowed to jump on the ol’ girl for a few demonstration laps between races with some other past AMA competitors like Dale Quarterley.

If you’re going to be around Monterey for this epic weekend, pop down to the pits, find us and say hello.

God, I hope one of us Vintage Dorks don’t blow an engine and spooge oil a mile long on the racing line just 10 minutes before the start of the next race…

– MM

Related reading:

More by Mark Miller

Comments

Join the conversation

Best time of the species was the late 80's - early 90's when improvements were leaps and bounds. Today, incrementalism because the bikes are already so good. Great story.

The writing from Mr. Mark Miller, took the reader through a masterful ride of which I could only dream.