Ducati Monster 1200S, Indian FTR1200 and 1200S Shootout at the Yamaha XSR900 Corral

None of these things are quite like the other ones

As the philosopher said, a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds. What were we supposed to compare the new Indian FTR1200 to?

On my first ride of the FTR back in May, those exhaust pipes said Ducati Monster to me, and the Monster 1200S has also been upgraded since last we rode one, so that was easy enough. I admit that the Yamaha XSR is a bit of an outlier: It’s an 847cc Triple going up against a pair of 1200 Twins. But when I saw an XSR a while ago in Yamaha’s warehouse, at a distance, I actually asked, “who’s old flat-tracker is that over there?”

With the XSR, Yamaha was gunning for the same look as the Indian, at least. So why not? The bike’s been around since Tom Roderick glowingly reviewed it in 2016, but we’ve never actually tested one in a group setting. So we brought Tommyguns back, too, to defend the Yamaha. Cheers.

In another unprecedented MO move, FAIK, we have two Indians – base model and “S” – mostly because Indian made both conveniently available to us, and so why not? The S model gets you a 4.5-inch TFT display, lean-sensitive ABS and traction control, Rain, Sport and Standard ride modes, adjustable suspension, and a $2k larger price tag: $15,499.

Crucially, both FTRs get standard cruise control, and by now you know how partial we are to CC (neither the Yamaha nor the Monster offer it). The standard FTR also gets regular ABS, glossy black paint, and a single round instrument nacelle instead of the TFT.

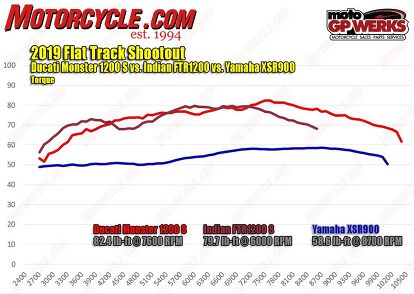

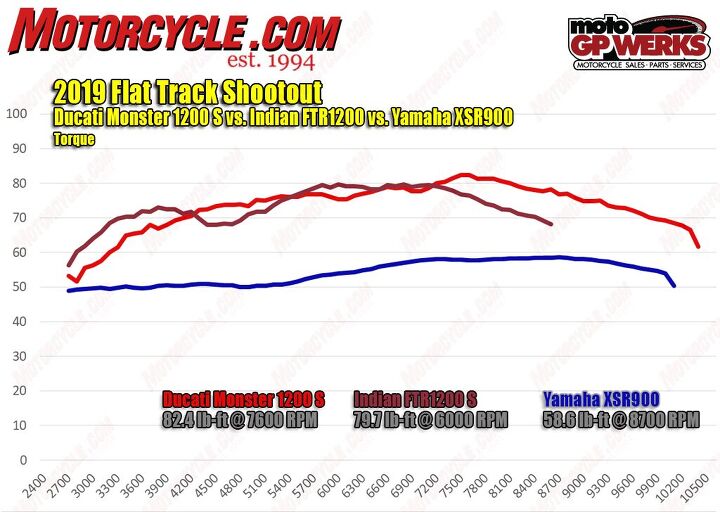

Horses for Courses

Everybody bags on the Indian’s teeny, 3.4-gallon gas tank, and the engineers defend it by saying the FTR is designed as an around-town bike, really, an urban trawler. Of course that’s a crap excuse, but in truth the FTRs really are fantastic for blasting around town; you sit nearly upright on a cushy seat and grasp a wide handlebar. Six inches of well-damped suspension travel at either end means bad pavement is no big deal, and 70 pound-feet of torque at 3000 rpm says, “what traffic?” when the light turns green. (The whole 80 lb-ft. arrives at just 6000 rpm.)

Naturally, then, we subjected the FTR to mountain roads that would doubtlessly favor the lighter, smaller Ducati and Yamaha and their 17-inch sport tires – in particular, the supertight, supergnarly and heavily tar-snaked Mt. Wilson road.

The kids whined and moaned that the FTRs were slow- and heavy-steering (which you’d expect given 5.1 inches of trail, the big 19-/18-inch wheel/tire combo, longest wheelbase and heaviest weight), and they are slow- and heavy-steering. But they also have a big wide handlebar, and when you put forth the effort, the FTRs go surprisingly well. On the Ducati, I had to work hard to not quite stay on pace with the FTRs going downhill. The upside of big wheels is that they store a lot of gyroscopic force, which instills confidence on crap, or no, pavement: There’s a reason why there’s a maximum wheel weight in flat track racing. And those custom Dunlop DT3 tires seem to have plenty of grip right to the edges.

The lean-sensitive ABS and TC should instill even more confidence (if you can keep in mind whether you’re currently on the “S” or not), but in fact neither Indian frightened anybody all day. Subconsciously we expect American motorcycles to run out of ground clearance early and often; nobody drug so much as a footpeg feeler on either Indian.

The Yamaha was the hot set-up on Mt. Wilson Road, though. At 436 pounds, it’s 75 pounds lighter than the Indians and 40 less than the Monster, and its sweet handling and smooth, linear power delivery let you know it’s not Yamaha’s first rodeo.

Uphill, though, the big Twins are a blast to ride. The Monster’s the only bike here with a quickshifter, which makes dropping into second gear effortless, and from there, there are few greater moto pleasures than whacking open a growler of big V-Twin torque. Play with the buttons and you can dial back the TC and wheelie control if you so desire. The desmo Duc slingshots you into the next corner, and its best-in-show Brembos haul you down so efficiently you wonder why you’re going so slow?

The FTRs feel a little like supersized Monsters: That same second-gear lunge is there, even slightly more. The rear Dunlop wavers a bit more than the Duc’s Diablo Rosso III as it zots the FTR off in pursuit of the other bikes, but the wide bar gives you the impression you’re in complete control. Sport mode on the S bike can be a bit jerky; the base model’s only mode has the same map as the S bike’s Standard. It’s pretty just right.

There’s no quickshifter on either Indian, but both gearboxes work perfectly acceptably if not quite as snick-snickily as the Yamaha’s, and their slip/assist clutches are fine too (once you adjust to the narrowish engagement band).

FTR front brakes are dual 320mm discs versus the Monster’s 330s, and the FTR’s Brembo four-piston calipers are a lesser version than the Duc’s M50 Brembos. Stir in the FTRs’ greater mass, and it can’t stop as hard as the Ducati or the Yamaha. But it still stops really hard, with good feel and linearity.

Mt. Wilson Rd flows to the faster curves of Angeles Crest; Angeles Crest flows to the ocean. Well, it flows to the LA basin anyway. On the Crest, the FTR continues to not embarrass itself in the company of the lighter motorcycles built by companies with decades of racing experience under their belts, though the faster you go the more you wish the handlebar was a little narrower and lower. Under the weight of the Scorecard, I’m forced to admit that the Monster 1200 and the XSR are both superior motorcycles for attacking mountain roads and closed circuits, but I for one am happily surprised that the FTR sticks as close to them as it does, exhibiting no glaring faults whatsoever.

It has a different feel for sure, thanks to what feels like more unsprung mass at both ends in the form of those big tires and wheels, but of course you adjust, and after a while, the FTRs feel like separate but nearly equal ways to skin the same cat. For a company to build, as its first sporty effort, a motorcycle as good as both FTRs, is really quite a feat. Some American motorcycle companies have failed at the task repeatedly.

Tommy Roderick:After pitching two perfect games, first with the Chief and then the Scout, Indian’s new FTR falls short of perfecting the moto-trifecta. Indian’s recent domination of dirt oval racing and the slow drip of information and images leading up to the release of the street-legal version of its flat track racer certainly had my anticipation juices flowing. My expectations may have been too much to live up to because as I spent the day aboard FTR and FTR-S I could feel my enthusiasm for the motorcycle draining from me like a slowly deflating balloon.Let’s not confuse my previous statement with the FTR being a bad bike; it’s not. The FTR is just longer and heavier than what I expect a flat track-inspired motorcycle to be. In the tighter sections of our twisty mountain road testbed, the wide handlebars adorning the FTR were put to good use leveraging the big bike from one side to the other. You can hustle the FTR when needed, it just takes a lot more effort to do so.

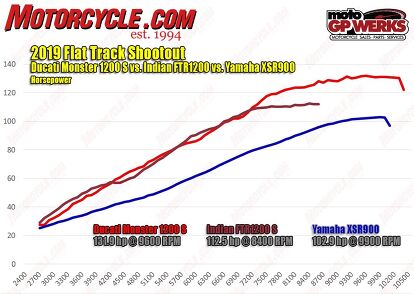

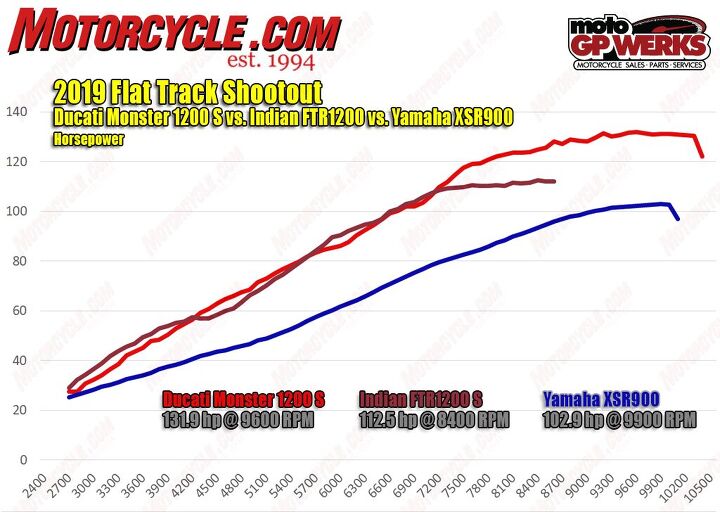

Perhaps, I set the FTRs up for failure by building them up in my mind for so long. Maybe, it’s the association with the FTR750 that has been kicking ass and taking names in American Flat Track. Whatever it is, my initial impression of the FTR was that I was underwhelmed. Then I rode the FTR some more.What I really like about the power delivery is how much torque is available down in the tachometer’s basement. Tremendous, smile-inducing grunt. Just look at the dyno sheets. However, it’s not all wine and roses in the power production front. There is a sizable dip in both the torque and horsepower in the 4,000-5,000 rpm range, but get through it and yowza! So, I took this to be two different riding styles. In the first, I’d just surf the torque curve, running a gear taller than I’d typically expect to do. This worked great in tight, low-speed sections of road or in traffic. However, when I really wanted to get my ya-yas out, cranking the throttle above 5500 did the trick. All the way to redline. In that rpm range, the FTR could hang with the Monster – until it ran out of revs. Then the Duc would just keep on going with 20 more ponies.

In my opinion, as a category-busting motorcycle, the FTR was destined not to finish very high in a situation like this test, where categories matter. That said, for style points and cool factor, I think the FTRs easily win this test. As a styling exercise Indian nailed it – on the first try, too. It’s a good looking motorcycle, and it goes well, too. Sure it steers like a truck, and the heavy flywheel effect means it revs slow, but the fact that I can haul ass up a mountain on an Indian-badged motorcycle at all is impressive in itself. When it comes to fun factor, the FTRs are a hoot. It’s not often I ride motorcycles I feel comfortable doing both wheelies and rolling burnouts. I could do them on the FTR.

Meanwhile on the Monster…

The Monster got an overhaul in 2017, gaining Ducati Quick Shift and cornering ABS, among other goodies. Ducati says it’s “more compact, slimmer and with sportier proportions,” and the clamp that holds the gas tank on in front, like the original M900, is back again.

I suppose Troy is correct: why would they change a motorcycle that’s been so successful? On the other hand, I’ve been saying the left side of the bike looks like the underside of a refrigerator ever since they went to liquid cooling. Is there nothing that can be done?

Other than its now dated look, what’s not to like about a bright red standard motorcycle that makes 132 hp worth of 90-degree V-twin racket, goes exactly where you aim it, likes to do nose wheelies and rides on lovely Öhlins suspension? The quickshifter works great too, and seems to have solved our biggest issue with the previous Monster: its dodgy gearbox. No cruise control though. Why not?

You’re canted slightly more forward on the Monster than the other bikes, and its footpegs feel a skosh higher; it’s a bit sportier than the FTRs and XSR, and if you’re large it may be more cramped than they are. In fact, a glance at our Scorecard reveals the Monster finishing last in Ergonomics, with an 82.5%, to the other bikes’ 88% scores. The Duc swept our Engine, Braking, and Suspension categories, and three out of four of us ranked it numero uno.

Tommy says:The only real naked sportbike of the bunch, the Ducati Monster 1200S exudes prowess and leaves the FTR gasping for breath in any twisty road competition. But at nearly double the price, the Monster is embarrassingly expensive when Yamaha’s $9,500 XSR is nipping at its heels at every turn. In fact, about the only time the Ducati truly outperforms the Yamaha is exiting tight corners, using every bit of torque available from its larger displacement engine to romp away quickly, only to be gathered back up by the XSR when braking into the next corner.In true sportbike fashion, the Duc folds its rider into a much more cramped position than the other two motorcycles, especially in the knee-bend area.It’s the prettiest bike from the right side, and an abhorrent arrangement of cooling tubes from the left.

The Monster is the purest sportbike of the group, and that Testastretta 11° engine lets you know it every time you let it run out through the rpm range. Yes, it’s got stonking torque that allows you to play in the tight, twisty stuff, but give’r a twist when the road opens up – yeehaw you’re in for some fun.The rest of the bike is what we’ve come to expect from a Ducati S model. The Öhlins suspension is as impressive as ever, and the Brembo M50 calipers delivered the best stopping power and feel of the bunch.The Monster’s been around long enough that we all know its flaws and either accept them or look for a different bike. Yes, the exhaust does heat up your leg and the seat area. All of the componentry stuck to the outside of the engine takes away from some of the 90° V-Twin’s inherent beauty. While the upper body’s riding position is relatively relaxed, the Monster does fold your legs up in a fairly sporty position – which is fine for apex strafing but can get a bit tiresome in commuter mode.And then there’s the price. The Monster 1200S is the most expensive bike here, but it walks the walk with its superior performance.

The Ducati does your typical Ducati things. It goes like stink. It handles like a sportbike, and it stops on a dime. Is anyone surprised? You know, it must be hard being on the design team for the Monster; you’re essentially set with the original Miguel Galluzzi framework, but you can’t deviate much. That said, after all these years, the iconic Monster silhouette and Ducati red paint are still attractive. Clearly the Monster was going to win our performance categories, but having ridden it around the city a bit, I would only want to commute on it sporadically, if for no other reason than the massive exhaust heat cooking my thighs and my arse. Factor in the price, and you must really want the Monster to justify the purchase.

One brilliant iconoclast, however, ranked the Monster third, and even though the Ducati takes the overall win in the Subjective portion of the Scorecard, the Italian bike’s lofty price tag wounds it badly in the Objective category. And so the Monster finishes second in this shootout to our somewhat surprising winner.

Surprise! It’s the Yamaha

Building a commanding lead with its light weight and low price in the Objective scoring, the XSR then ran away with the win thanks to its super-competent performance and comfort. It won our Handling and Comfort categories – and the least expensive bike here also emerged on top in Quality, Fit and Finish. The XSR even crushes the competition in Grin Factor, where Tom gave it the only 10 on the card.

The XSR only makes a measly 102.9 horsepower at 9900 rpm, but then it weighs a mere 436 pounds gassed up. You could spend days trying to determine if that three-cylinder howl is more soulful than the big V-Twins’ bark. It’s just you and the MV Agustas and Triumphs.

If you’re a grain-fed midwestern gal, you might prefer the FTR’s more expansive layout, but for most of us kale-munching coastal-elite lane splitters, less is more. Though the Yamaha’s ergos are just as upright as the Indians’, its handlebar is a bit narrower, as is the whole motorcycle, and that skinniness and light weight are just the tools for urban warfare.

The Brasfield Opinion:When we decided to include the XSR, I figured it would be a fun motorcycle that could provide some of the enjoyment of the larger, more expensive bikes in the shootout. My plan was to see what the rider had to give up to enjoy the $9,500 retail price. While it is true that the XSR doesn’t have some of the features of the other bikes, I was surprised to see that, instead of trailing along in a close third place (as I expected it to), it had the potential to win this shootout.Say what?The Yamaha XSR900 is one of those Goldilocks motorcycles that ticks off so many of the right impressions that it can overcome its apparent weaknesses. First, it has its low price and light weight – two things that the scorecard does favor. No, it doesn’t have the tendon-stretching power of the Ducati and the Indians, but what it lacks in brute force it makes up in linear torque and horsepower. And then there’s the sound of the Triple.

The XSR not only harkens back to yesteryear with its styling and color schemes, it reminds me of when motorcycles were less specialized and just meant to be cool toys that you could also commute to work on.Could be I’m biased due to my affection for odd numbers and asymmetrical design, but I love the Triple powering Yamaha’s XSR. In fact, the XSR is my choice for the best three-cylinder Yamaha has yet produced.

As a cheapskate, I have no other option than to like what the XSR brings to the table. This fun and capable motorcycle punches way above its weight, but won’t knock out your wallet, either. I happen to think it’s more cafe racer than street-tracker, but whatevs. Really, there’s not much more I can say about the Yamaha that the other fellas haven’t already said. Here’s my thing: From where I’m standing, I don’t see myself cross-shopping the Yamaha with the Indian. Both bring different things to the table, and that table is occupied with a different set of potential customers. Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t think so.

Okay so the XSR Wins, But Here’s the Thing:

We rode them in the mountains because that’s what we always do; if you’re riding around in Nebraska or someplace where there are more dirt roads than mountain ones, the FTR’s big tires move the bike about a third of the way toward being an ADV. At the FTR’s coming out party, in Baja, we spent half the time off pavement and in quite a bit of sand. You wouldn’t want to do that on the Monster or the XSR. The FTR’s performance envelope is broader.

Maybe because it’s made in Spirit Lake, Iowa, these Indians have me pining for the midwest. Not really, but if you’ve ridden around there much, you understand how carrying a few extra pounds around is no big deal, especially if it takes the form of more room for two on top of the bike, rolling out for a dip in a nice farm pond on a warm night. Ahhh… burbling along through the corn fields or on the beach at Daytona, you might even be able to appreciate the cruise control. Then again, you might wind up even more frustrated by the tiny fuel tank.

The Indian does have a small gas tank, it does buzz a bit through the bars between 70 and 85 mph, and it does put out a bit of heat on the right side: Nothing like Panigale heat, but heat.

I wouldn’t be surprised if we coastal elites appreciate the FTRs quite a bit less than the rest of the country will. Indian’s mission with the FTRs may be less to unseat people from Ducatis and Yamahas than to pry middle American butts off of other popular American motorcycles. That will depend on many factors more important than the last nth of performance on Angeles Crest Highway – (and the fact that the FTRs perform as well as they do up there is icing on the cake).

I, JB, must admit I was the lone MOron to rank the FTR1200S number one on the Scorecard (with the XSR less than a percentage point behind it). I’m also a fan of Buells and American muscle cars and cheese grits. I’m sad that the FTR finished last here. I think the big knobbies look cool AH, and the thing’s even got a compass, for God’s sake. I can’t wait to see where it leads Indian’s engineers next.

In the meantime, enjoy your Yamaha XSR, it’s a great bike too. For now, I will admit defeat and ride off into the sunset on my FTR, cruise control set at 85-ish.

| Scorecard | Ducati Monster S | Indian FTR1200 S | Indian FTR1200 | Yamaha XSR900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Price | 54.6% | 61.3% | 70.4% | 100% |

Weight | 91.6% | 85.3% | 85.3% | 100% |

lb/hp | 100% | 79.3% | 79.3% | 86.0% |

lb/lb-ft | 100% | 90.6% | 90.6% | 78.4% |

Total Objective Scores | 82.1% | 77.2% | 80.2% | 94.1% |

Engine | 91.3% | 86.9% | 86.9% | 90.3% |

Transmission/Clutch | 91.3% | 81.3% | 81.3% | 86.9% |

Handling | 89.4% | 80.0% | 80.0% | 92.5% |

Brakes | 92.5% | 86.3% | 84.4% | 86.9% |

Suspension | 93.1% | 88.8% | 85.0% | 88.1% |

Technologies | 91.9% | 93.1% | 83.8% | 83.8% |

Instruments | 93.8% | 93.8% | 82.5% | 84.4% |

Ergonomics/Comfort | 82.5% | 88.1% | 88.1% | 88.8% |

86.9% | 90.0% | 90.0% | 90.6% | |

Cool Factor | 84.4% | 90.0% | 90.0% | 83.1% |

Grin Factor | 88.8% | 84.4% | 84.4% | 93.1% |

John’s Subjective Scores | 89.8% | 91.0% | 89.4% | 90.2% |

Evans’ Subjective Scores | 90.2% | 87.1% | 85.6% | 88.8% |

Troy’s Subjective Scores | 87.5% | 83.3% | 80.4% | 84.2% |

Tom’s Subjective Scores | 91.5% | 88.3% | 85.6% | 89.8% |

Overall Score | 88.2% | 85.4% | 84.3% | 89.4% |

| Specifications | Ducati Monster S | Indian FTR1200 S | Indian FTR1200 | Yamaha XSR900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSRP | $17,395.00 | $15,499.00 | $13,499.00 | $9,499.00 |

| Type | 1198cc liquid-cooled Testastretta 90-degree V-twin | 1203cc liquid-cooled 60-degree V-twin | 1203cc liquid-cooled 60-degree V-twin | 847cc liquid-cooled inline 3-cylinder |

| Bore and Stroke | 106 x 67.9mm | 102 x 73.6mm | 102 x 73.6mm | 78.0mm x 59.1mm |

| Fuel System | EFI, Ride-by-wire, two 56mm equivalent oval throttle bodies | Closed Loop Fuel Injection/ two 60mm throttle bodies | Closed Loop Fuel Injection/ two 60mm throttle bodies | Yamaha Fuel Injection with YCC-TY |

| Compression Ratio | 13:1 | 12.5:1 | 12.5:1 | 11.5:1 |

| Valve Train | Desmodromic; 4 valves/cylinder | DOHC, 4 valves/cylinder | DOHC, 4 valves/cylinder | DOHC; 4 valves/cylinder |

| Drive Train | ||||

| Transmission | 6-speed; hydraulic slipper clutch | 6-speed; slip/assist clutch | 6-speed; slip/assist clutch | 6-speed; slip/assist clutch |

| Final Drive | Chain | Chain | Chain | Chain |

| Front Suspension | 48mm inverted Öhlins fork; fully adjustable; 5.1-in travel | 43mm Sachs inverted cartridge fork; 5.9 inches travel | 43mm Sachs inverted cartridge fork; fully adjustable, 5.9 inches travel | 41mm inverted fork, adjustable preload and rebound damping; 5.4-in travel |

| Rear Suspension | Öhlins single shock, linkage-mounted; fully adjustable; 5.9-inches travel | Sachs single shock; adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping, 5.9 inches travel | Sachs single shock; fully adjustable, 5.9 inches travel | Single shock, adjustable preload and rebound damping; 5.1-in travel |

| Front Brake | Dual 330mm discs; Brembo M50 4-piston calipers; Bosch cornering ABS | Dual 320mm discs; Brembo 4-piston calipers, ABS | Dual 320mm discs; Brembo 4-piston calipers, cornering ABS | Dual 298mm discs; ABS |

| Rear Brake | 245mm disc; 2-piston caliper, Bosch cornering ABS | 265mm disc, Brembo 2-piston caliper, ABS | 265mm disc, Brembo 2-piston caliper, cornering ABS | 245mm disc; ABS |

| Front Tire | 120/70-ZR17 | 120/70R-19 | 120/70R-19 | 120/70-ZR17 |

| Rear Tire | 190/55-ZR17 | 150/80R-18 | 150/80R-18 | 180/55-ZR17 |

| Rake/Trail | 23.3° / 3.4 inches (86.5mm) | 26.3° / 5.1 inch | 26.3° / 5.1 inch | 25.0°/4.1 inches |

| Wheelbase | 58.5 inches | 60 inches | 60 inches | 56.7 inches |

| Seat Height | 31.3 or 32.3 inches (adjustable) | 31.7 in laden/ 33.1 in unladen | 31.7 in laden/ 33.1 in unladen | 32.7 inches |

| Curb Weight | 476 lb. | 511 lb. | 511 lb. | 436 lb. |

| Fuel Capacity | 4.4 gallons | 3.4 gallons | 3.4 gallons | 3.7 gallons |

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

The fact that a bike Indian built to compete with HD Sportsters is even in the same ZIP Code as these bikes is reason enough to be enthusiastic about it. Whatever Indian’s next iteration of “sporty, standard, tracker, ADV” bike is, it ought to be interesting...

LOL - "coastal elites" - that's about 70% of the US population depending on yer definition - or are the only tru americans found huddled in an Idaho basement wrapped in aluminum foil. LOL