The Clay Modeler Bringing Motorcycle Designs To Life – Part 1

Behind every good designer there's a clay modeler

Here is a group of names you’ve probably heard of: Massimo Tamburini, Miguel Galluzzi, Gerald Kiska, Hans Muth, Adrian Morton, Pierre Terblanche. Hell, even if you don’t know these names, you’ve definitely seen their work. These are the men responsible for some of the greatest contemporary motorcycle designs in all of history. But have you ever thought about how a design goes from a napkin sketch and turns into a real-life motorcycle? There must be a process by which a 2D rendering transforms into a 3D object.

Nick Graveley is the man (well, one of them, anyway) tasked with doing exactly that. It’s designers who get all the glory (or wrath, if you’re Terblanche), but deep in the trenches, Graveley is shaping clay and bringing to life these designs born from someone else’s mind.

It’s a shame clay modelers like Nick aren’t as widely known, because there’s a decent chance you’ve seen his work or even own a motorcycle he’s modeled in clay. OEMs like BMW, MV Agusta, KTM, Hero Motor Corp., Husqvarna, Royal Enfield, Triumph, and Zero are just a few of his current and former clients, and some of the bikes he’s had a hand in shaping include the BMW S1000XR, C Evolution scooter, various K1600s, MV Agusta Turismo Veloce, Zero SR/F and SR/S, KTM 450 SX-F, 1290 Super Duke GT, and even KTM’s RC16 MotoGP bike – just to name a small few.

Recently, through the miracle of technology, Motorcycle.com had the chance to sit down (virtually) with UK-born Graveley from his home in Munich to talk about clay modeling, bringing motorcycle designs to life, and where things go from here. In talking to Graveley, what surprised me was his ability to juggle being agnostic about the design, while also being on the cutting edge of methods to achieve his job quickly, efficiently, and with minimal cost. At the same time, his enthusiasm when it comes to getting down and dirty with clay is infectious.

Before we go any further, know that he doesn’t have a favorite. It’s like when we get asked what our favorite motorcycle is. The answer depends. There are so many cool bikes, all filling a particular niche, that choosing one above the rest is just too hard.

Tell us, exactly, what do you do?

NG: I work with a lot of different OEM’s around the world. Well actually not just OEM’s; some custom bike manufacturers or parts manufacturers too. They phone me up or send me an email and they go, “We’ve got a project. We need a clay modeler for this to come in and work with us and a designer.” So, they’ll have a designer, they’ll have a design laid out, and they will basically need that design turned into a full-scale clay model, and that’s where I come in.

Normally, where I come in, they’ve been through a loop of digital development, so they will have had a digital modeler take a stab at taking whatever the sketch is and then putting it over the package if there is an engineering package. They’ll try and model some surfaces over that. Over the last five or six years, it’s much more common that they’ll mill out those surfaces previous to that. But it’s not uncommon to start from zero and actually just be roughing in foam and roughing in clay and starting from scratch.

Now, normally when I turn up day one at the studio… we’ll be trying to figure out what is worth keeping. Ultimately, it all gets changed. Nothing stays the same. In my opinion, the poly-modeling phase of it has up until now been kind of, not a total waste of time, but I’ll just segue quickly into what I’m doing now with VR. I’m actually taking on some of that early development work and developing that in the VR environment. What I then come up with at the end of the VR loop would be what was milled out of clay, and then we’ll move through the further development in the clay.

So, to get back to your question, basically I’m working with the designer and to some degree the engineers, to basically get the design intent into a full-size motorcycle model that we can sit on and we can stand back and look at. Basically, it’s that balancing act between styling, engineering and ergonomics, and also manufacturer ability, but that comes at a later stage.

Normally in bigger OEMs, there are three different models. There’s a concept model, then the engineers get involved. There’s a tighter model where you’re trying to get it really on the engineering package, and then there’s a last model which is really where all the panel gaps are right. Sometimes you’ll step one panel down through another panel. There’ll be like a millimeter step engineered into it so that you don’t see into a panel gap or something. That will all be in that last model. In a nutshell, that’s what I do.

How does one even get started doing this? What is your background?

NG: I really wanted to be an airline pilot like my father. I found out just before I had to choose what class I wanted to do at university that my eyesight wasn’t good enough to be a pilot, so I very quickly had to decide some new course for my life. I decided that I quite like cars, I quite like drawing things, and I decided to sign up for Coventry University’s Transport Design degree. Miraculously, I got on the course. I don’t know how, because I had absolutely no real ambition. For the other people in the course, this is the only thing they wanted to do their whole life, and I decided a few weeks earlier. I got on the course and I went there and I did that course. It became quite apparent to me by about the third year that I didn’t want to be a car designer. I wasn’t good enough, and I wasn’t that into it. But then a friend of mine took me out on his motorcycle, and literally, that one journey changed the entire trajectory of my life.

Then there was a guy called Glynn Kerr who was a relatively well-renowned motorcycle designer, and he came and gave a talk on motorcycle design, and that was it. I was like, “Yup. That is what I’m going to do. Motorcycle design.” So, I finished my degree concentrating on motorcycles, and then I ended up getting through to Glynn again – he actually had a connection at a company in India that was looking for a designer, that was TVS Motor Company. I went there for three years working as a designer.

Because they didn’t have the segregation between design and clay modeling and stuff that you get in some of the bigger, Western OEM’s, I was able to do my own clay models. I realized that was really, really what I loved doing was making the models. The days when I was sitting at the computer sketching on Photoshop would just drag by. The days when I was up in the studio doing clay, I loathed when lunchtime came (mostly because the food was terrible!) and I could not believe when people were going home. That is still the same today. When the designer comes in and shouts, Mahlzeit (German for lunchtime) I’m like, “What? Is it lunchtime already?” And I can’t believe that it’s the end of the day when it’s the end of the day. I just get so into the work. That was basically my journey. A long-winded way of saying I used to be a designer, then I moved to clay modeling.

After that stint in India came a short six-month spell in Pattaya, Thailand, and it wasn’t my cup of tea. I left after six months and visited my sister in San Francisco, having lined up an interview at Honda in LA. There I completely surreptitiously ran into Neil Saiki, the founder of Zero Motorcycles, and offered to work with him whenever he was ready. That never materialized, but it’s crazy to think how I eventually circled back around to Zero a decade later to help clay model the SR/F and SR/S. Anyway, while I was in California I went for the interview at Honda in Los Angeles. They were looking for a designer, I wanted to be a clay modeler, so it didn’t work out (though I did score some contract work out of it). Eventually, I landed a contract with BMW, and I moved to Munich. That was 2006, and I’ve pretty much been here ever since.

In the course of that time, you’ve had your hands in how many different motorcycles that are running down the road today?

NG: I don’t know how many. A lot. It doesn’t even include the ones I worked on that didn’t make it out. Probably for every motorcycle that’s out there, there’s at least one model that I worked on that didn’t make it out, that was a proposal or something. Maybe not one for one, but maybe every two that went out, there was one that didn’t make it.

On finding work in 2020

NG: I’m super lucky. I have steady work. Most clay modelers that I know, certainly guys in the car industry, some of them haven’t worked the entire year. Just people canceled their projects. Part of the reason I shifted to motorcycles was not just because I love motorcycles, but to service a niche that nobody else was really doing. I’m kind of fortunate that I’m one of [the few guys doing this]. I don’t even know how many there are of us out there. Between all the OEMs, there are a lot of clay modelers out there, but there’s got to be a couple of dozen freelance specialists like me who are only doing motorcycles.

What is your process?

NG: The core values are the same as what everyone does, but I kind of have a little bit different way of doing things by incorporating scanning and now I’ve just started incorporating virtual reality. Essentially it will go from the designer’s sketch… then, if it’s an existing motorcycle package, like an existing frame and engine and it’s just a restyle or maybe there’s just some tweaks, like an update rather than a big, new bike launch, then there’ll be a lot of hard data that’s already there. We’re already quite ahead of the game at that point. We probably already know a lot of information, like fuel tank volume needed and the ergonomics will be fixed, more or less. The rider seat height will be fixed.

For a new model, they’ll do a digital model loop which will then be milled out of clay, and then I’ll turn up and start to hack away at it basically working with the designer, trying to figure out where to go with it, what are the most important parts of the design that we need to encapsulate in this model. The thing is, no matter how beautiful a sketch is, it is just a sketch. It never transforms directly into 3D.

In a studio like the big OEMs use, they’ll have these big, steel plates, and they’ll have these enormous coordinate measuring machines that slide along the length. You use that after you get information from the engineering team and put it into the model. That first digital model is normally called a poly model. They’ll mill out both sides of that, and then typically you’ll only work on one side of it. But when you’re only working on one side of it, you’re not really understanding what you’re doing to the overall width of the bike. So you might be doing the top of the fuel tank, for example, and you don’t really have an appreciation of what that’s going to look like once it’s mirrored over. So, I stick a mirror there, which is what you do as a student. For some reason, as soon as you get into a professional studio, they completely abandon this thing, presumably because it’s seemingly amateurish or something. But in terms as a device to help you, it’s incredible.

Then it’s just a process of managing a time plan. You’ll know how long you’ve got for this project and you’ll work back from the end date. Then you tell the designer, “at this point we freeze the design. No more changes from this point.” I never yet had one [designer] that’s gone, “Okay, fine.” They always, always keep wanting to change stuff up until the last minute. That’s part of the job.

You want to accommodate what they want, all these changes, but at some point, the quality of the model is going to suffer if I don’t spend that last week really cleaning everything up and making it perfect. A motorcycle is such a dynamic object compared to a car, for instance. You’ve got these panels that basically go between the gas tank and the rider’s knee. You’ve got to make sure that you’ve got enough gas volume. You’ve got to make sure the ergonomics are right and all that.

One of the important ones is handlebar clearance when you’ve got full lock on the handlebars. This is typically quite challenging in India, where the need for maneuverability dictates a large steering lock. So as soon as you get a 45-degree steering lock, you push any front fairing forward or super narrow, and the bars will hit the fuel tank.

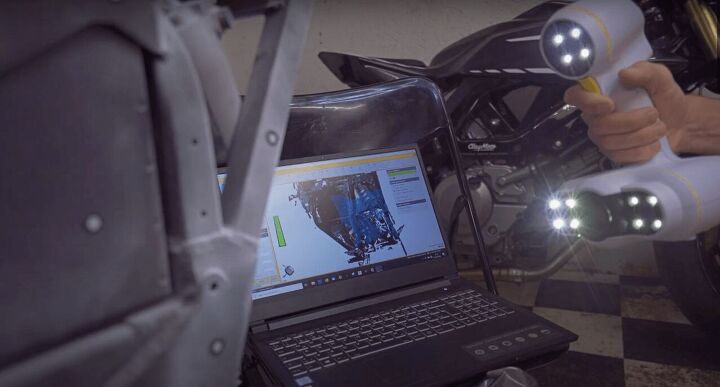

I started using this Peel 2 scanner from a company called Peel 3D – I didn’t get a plug in there for this company. You can basically take a scan of an area, and it’s sufficiently accurate at volumetric accuracy of 0.5mm/m3. In about ten minutes, you can scan an area and then overlay that onto the engineering package, which has got all the clearances in it. You can check that the surface you’re making is not going to have any interference issues.

What is the most challenging aspect of this job?

NG: I don’t really know. I love it all, really.

C’mon

NG: There are lots of challenges, but I don’t know that I find anything insurmountable. The hardest part is maybe people management. Not every designer is created equal. Some are more experienced than others. Maybe, for example, we try to find a set area where we haven’t really hit the nail on the head yet, we haven’t really got it. So, they’ll go away and do some sketching and come back. Or maybe they won’t even spend a second to do a second sketching. He’ll be spouting off some ideas. “Hey, just do this. Pull this back. Pull that out.” I’ll maybe have to say, “Yeah, but if we pull all that stuff out, then it’s going to change all this other stuff, and ten minutes ago that was the most important thing in the world to you.”

Probably the hardest thing for me is having such a comprehensive understanding of how surfaces work and then working with people that don’t have that same understanding of how surfaces work, and how if you change one thing it will affect everything around it.

I absolutely detest people who want to try and bring other people down. I would never say anything in a way that tries to belittle someone about how you don’t understand anything. I just want to make them understand these are the repercussions of what they’re saying. That can be quite difficult for me sometimes to say it in the right way and say, “Actually the way I understand your idea, it’s going to look shit.” They wouldn’t be like, “I know, but…” And I’ll have to say, “This surface is going to do that. That surface will do that, and we might have to draw a few sketches or something to get to the same understanding. Now, do you agree it’s going to look shit?” Then we can come to a solution that serves the design intent and looks awesome.

In part two of Motorcycle.com’s interview with Nick Graveley, we’ll obviously talk more about his work, but we’ll also take a deeper dive into virtual reality and how it represents the next frontier in bringing motorcycle designs to life. Stay tuned.

If you want to see more of Graveley’s work, be sure to follow him on Instagram ( @claymoto_design) or visit his website, claymoto.com.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

Awesome content, MO. Keep this stuff coming. I'll click on the commerce posts.

So... fair warning... my day job is selling large industrial 3D printers that could directly print some of the parts he's modeling in clay... I'm very curious to read part 2 and see what he's doing with VR. Certainly lots of people are using 3D scanning - then reverse engineering to print the part... The challenge remains - how do you take a beautifully rendered 2D image on a computer screen and turn it into a 3D object... We are working on taking images from Keyshot (a rendering software) and going directly to a 3D printed part with color and texture - but we can't do it at the scale he's working in... we'd have to do smaller pieces and glue them together...someday...