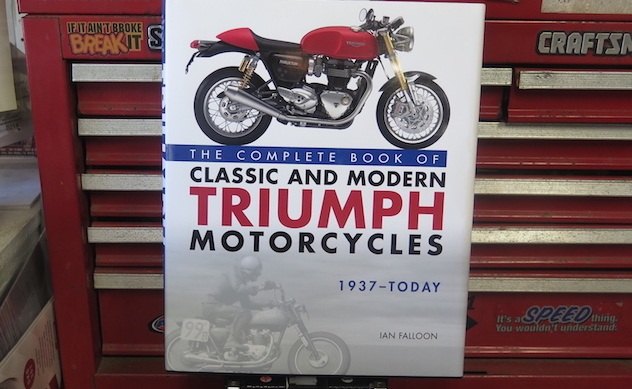

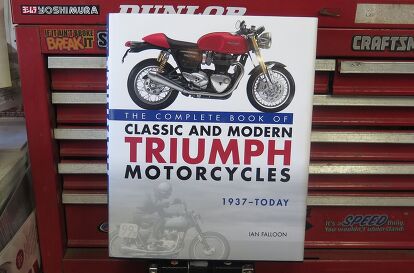

MO Books: The Complete Book of Classic and Modern Triumph Motorcycles 1937-Today

-by Ian Falloon

Ian Falloon is known mostly for his excellent work about Italian motorcycles; this is his first British bike endeavor, and feels like a huge undertaking given Triumph’s beginning in 1902: 1885 really, if you count the bicycles. This is the revised and updated version of the book Falloon originally published in 2015.

We start at the very beginning. What’s in a name? Siegfried Bettman, a German emigrant, began building bicycles in Birmingham for export throughout Europe. Worried that “Bettman” didn’t sound English enough, he changed the company name to Triumph, and the business began to prosper.

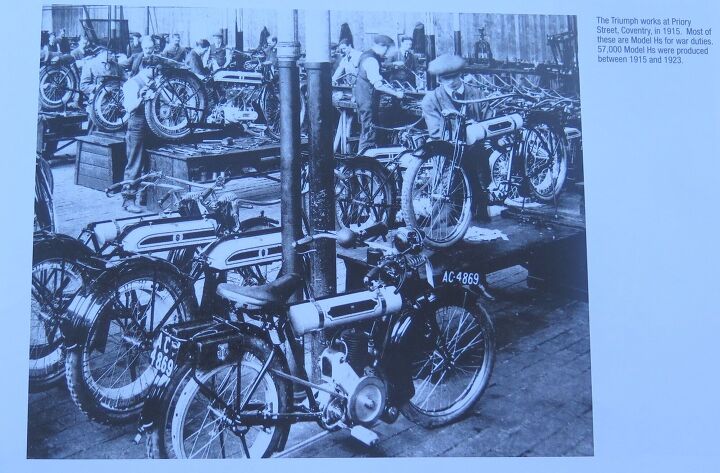

In 1902, we’re attaching a Minerva engine from Belgium into a bicycle; by 1905 Triumph’s built its own 363cc engine (3 hp at 1500 rpm), and by 1909 3000 Triumphs are produced at the Coventry factory. Being tasked to build 30,000 Model Hs for WW1 didn’t hurt business. Somebody always finds a way to screw things up, though; along came the Great Depression, and by 1936 the decision was made to shut down the motorcycle division and concentrate on automobiles.

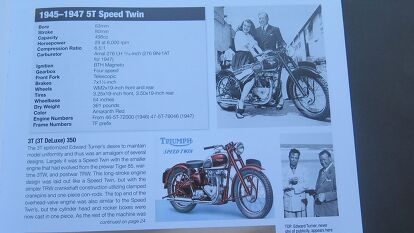

A last-minute deal was cut with the bankers, however, and Edward Turner enters the picture as managing director and chief designer: “… but it was soon quite obvious that he was the chief of every other department, from sales to engineering and styling…. Not only was Turner totally in charge, he was also confident and fearless operator.”

Falloon gives Turner the credit for being an early believer in the importance of styling: Overhauling bikes mainly with new chrome gas tanks and rubber knee grips, polished aluminum engine covers, and TT-style exhausts boosted sales. So did calling them Tiger 70, 80, and 90 – which referred to each models’ top speed.

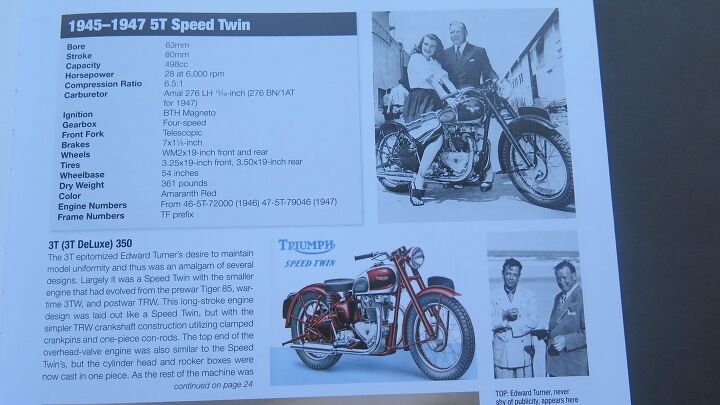

Turner had already designed the Square Four for Ariel, a motorcycle so advanced it continued in production until 1959. At Triumph, Turner used half as many cylinders in creating the 1937 Speed Twin, and reinvented the British motorcycle industry.

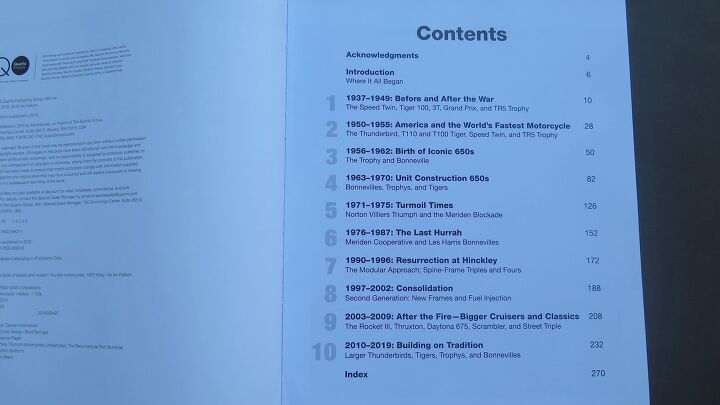

Right, this is all in the first 15 pages, and there are 257 more glossy, large-format, lavishly illustrated 10 x 12” pages to go. The book is broken down into ten chronological chapters, with each one providing a blow-by-blow of each new model and yearly changes. People with more attention span than I might read it cover to cover. For most of us, it’s a great reference source and a fantastic coffee table book.

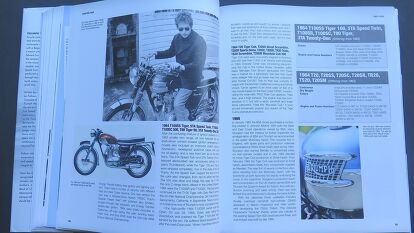

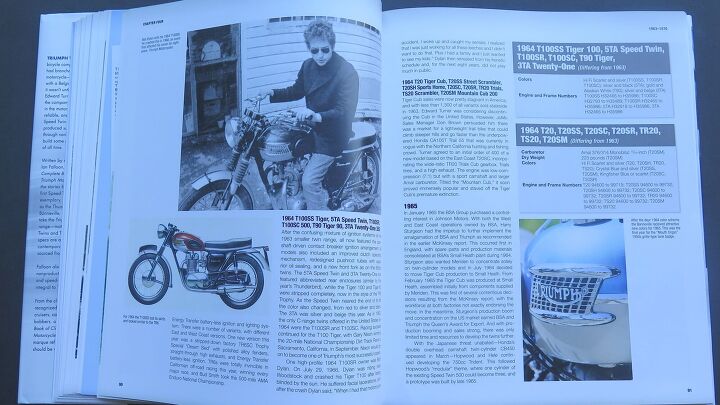

Everybody knows Bud Ekins did the motorcycle jump for Steve McQueen in The Great Escape, but did you know Ekins also drove the green Mustang through San Francisco in Bullitt? I had to pick that tidbit up from Mr. Falloon, a New Zealander, on page 79.

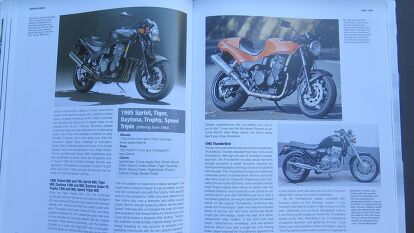

It’s all in here, your Amal Monobloc carburetors, Lucas ignitions, Zener diodes, Bob Dylan… and don’t forget the magazine test quotes. From Cycle World in 1964 re: the new Thunderbird: “We simply cannot find fault with the ride, and everything operates with great precision. In all, the Thunderbird impressed us as being very much the gentleman’s motorcycle. It has been as pleasant a motorcycle as ever offered to us for test.”

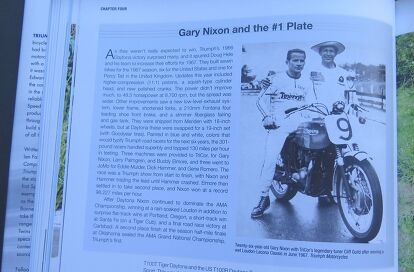

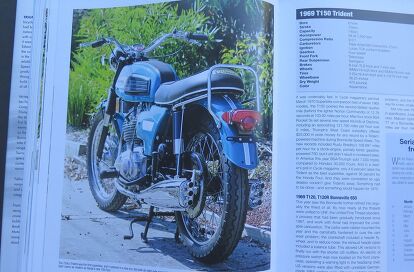

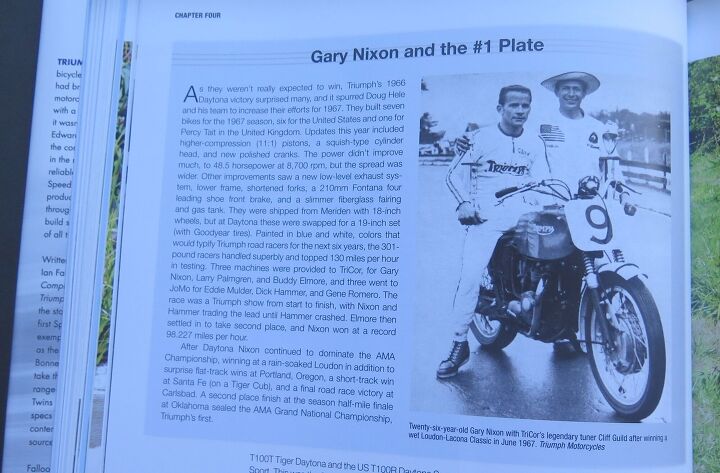

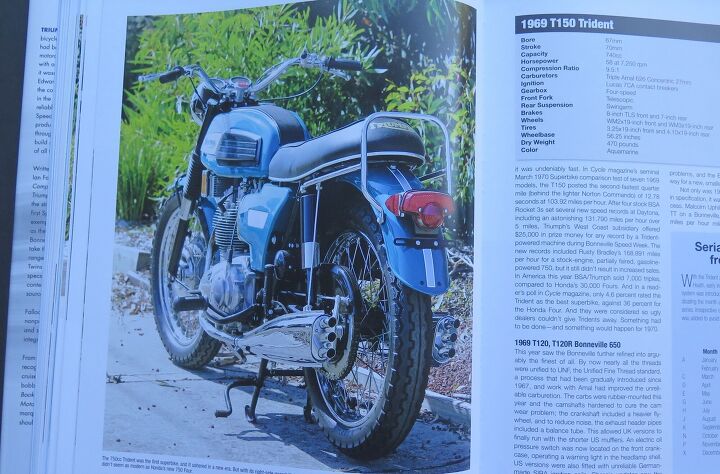

Yes there’s racing, including Gary Nixon’s first GNC championships for Triumph in 1967 and `68, followed by Gene Romero’s in `70. In 1969, the Honda CB750 appeared, and made the long-awaited Triumph Trident triple look like the brand new antique it sort of was: “The Trident may have been expensive, poorly manufactured, and afflicted with unusual styling, but it was undeniably fast…

… but it still didn’t result in increased sales. In America this year [1970] BSA/ Triumph sold 7,000 triples, compared to Honda’s 30,000 Fours. And in a reader’s poll in Cycle magazine, only 4.6 percent rated the Trident as the best superbike, against 36 percent for the Honda Four. And they were considered so ugly dealers couldn’t give Tridents away.”

Even though I’m old, all this precedes me. Triumph died a slow, lingering death through the `70s and early `80s. But in 1983, an English house builder and over-achiever named John Bloor acquired Triumph’s name and rights, after really only wanting the site of its Meriden factory to build houses upon: “It soon became evident that Bloor’s business philosophy differed substantially from that of Edward Turner… Rather than pursue immediate short-term profits with under-developed products, Bloor sanctioned all-new designs, underwriting the development costs for several years.”

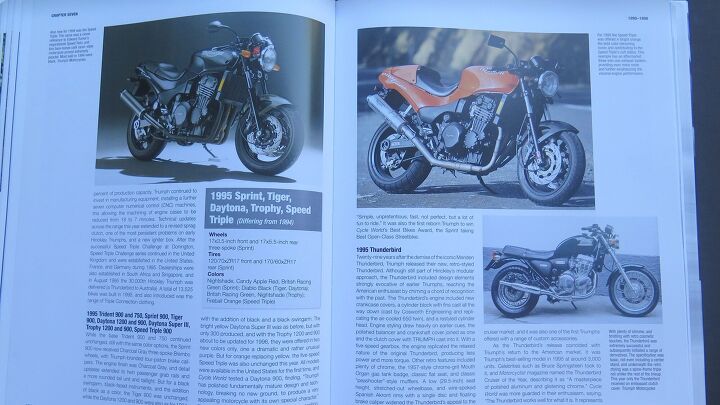

The name Triumph was legendary enough, but it, like all post-Honda British motorcycles, carried some reliability baggage. “Bloor thus decided on a conservative approach, promoting the new range as modern, not retro, and launching Triumph as a small, high-quality producer with the intention of eventually growing into a large-volume mainstream manufacturer competing directly with the Japanese.” By 1991, the new Triumph was building motorcycles powered by all-new 3- and 4-cylinder modular engines, and by 1995, it re-entered the US market with a new bike designed just for us – the Thunderbird.

Styled after classic Triumphs but powered by a snarly new 885cc Triple, the T-bird was a lot of fun to ride at its US debut in the company of then-Triumph PR guy Michael Lock (who went on to be Ducati NA’s CEO and now runs American Flat Track), and a couple of other motojournalists (Mark Tuttle and Jon Thompson). We named the new Triumph “Cruiser of the Year” at Motorcyclist magazine that year – and we’re still only on page 185 of this epic tale.

History’s a fun thing to watch. A few years later, Triumph remade the Speed Triple from a slightly clunky, heavy thing into one of the only motorcycles guys would ride even in pink (Nuclear Red, Triumph called it). It and the Ducati Monster launched a whole new genre of naked bikes, well, maybe refreshed us with motorcycling’s original genre, at least.

Here was a motorcycle company capable of competing head-to-head with anybody, and a sly British sense of humor along with it. Now with its New Classics, Triumph is risen from the dead, healthier than ever, and able to take the fight right back to the Japanese and Euros. It’s fitting that the book comes to a close at the end of the 2019 model year, the very one in which Triumph resurrected the name Edward Turner put onto the bike that launched the British era 82 years before: Speed Twin.

Great story. Great book.

The Complete Book of Classic and Modern Triumph Motorcycles 1937-Today

$50 US, $65 Canadian

ISBN: 9780760366011

Shop for the The Complete Book of Classic and Modern Triumph Motorcycles 1937-Today here

We are committed to finding, researching, and recommending the best products. We earn commissions from purchases you make using the retail links in our product reviews. Learn more about how this works.

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

Pretty cool. An excellent choice for a gift this Yuletide. I will be dropping the hint (and providing the link) to my wife .