2012 Triumph Scrambler Review - Motorcycle.com

Triumph’s Scrambler proved to be difficult to review. Judged against other machines in its $8799 price range, it’s kind of slow, a little heavy, and excels at nothing except being cool. In purely objective terms, it’s a mediocre motorcycle.

However, as we racked up seat time, the retro ride began to charm us in ways no other bike could. There isn’t another motorcycle on the market that has the Scrambler’s blend of nostalgia, versatility and general competence.

History

Triumph understands that nostalgia has a way of prying open wallets. The Hinckley-built Bonneville re-creations began rolling off production lines in 2000 using a fresh parallel-Twin engine design displacing 790cc. Since then, Triumph has built 147,000 of the twin-cylinder bikes that include the Bonneville variants, Thruxton, America, Speedmaster and the Scrambler, representing about 25% of Hinckley’s total production.

The Scrambler was launched in 2006, inspired by the late-1960s TR6C Trophy that featured a similar high-mount exhaust system but located on the bike’s left side. Its engine, now upped to an 865cc displacement, features a 270-degree crankshaft instead of the Bonnie’s typical 360-degree spacing to emulate the power pulses of a V-Twin engine. It’s a similar configuration to the America and Speedmaster cruisers. Carburetors gave way to fuel injection in 2009, with the throttle bodies cleverly disguised as old-school carbs.

The Scrambler receives several other modifications to distinguish it from Triumph’s other air/oil-cooled models in an attempt to give it some authentic 1960s desert sled appeal. In addition to the Scrambler’s revised engine and high-mount exhaust, it also receives longer-travel suspension, fork gaiters, spoke wheels and tires with large tread blocks.

The King of CoolSteve McQueen is an iconic figure revered by millions, but especially by middle-aged motorcycle enthusiasts. As an actor, he ignited the screen with performances in legendary films such as The Magnificent Seven, Bullitt, Papillon and the original The Thomas Crown Affair. In 1974 McQueen became Hollywood’s highest-paid actor when he co-starred with Paul Newman in The Towering Inferno.

But McQueen earned maximum credibility among riders for two films in particular. The Great Escape starred McQueen as Virgil Hilts, an American Air Force captain imprisoned in a German POW camp. The 1963 film is capped off with an escaping Hilts trying to evade recapture by stealing a German motorcycle and ditching his pursuers, climaxing with a glorious but unsuccessful jump over a barbed wire fence to neutral Swiss territory.

While any two-wheel fan can get excited by a motorcycle chase, what made this one special was the fact that McQueen did almost all of the stunt work himself, even doubling as German soldiers giving chase to his own character thanks to shrewd editing! McQueen’s best pal, Bud Ekins, stood in for the star during the famous jump scene, apparently because the film’s insurance company barred him from doing it himself.

Of note, the motorcycles chosen for the stunt work were not German BMWs as would be historically accurate. Instead, McQueen specified a military-spec Triumph TR6, a progenitor to the Scrambler tested here. And one year later, McQueen represented America in the 1964 International Six Days Trials on a Triumph.

McQueen also played a pivotal role in the seminal motorcycle movie, On Any Sunday, financing it via his Solar Productions company. He also played a prominent on-screen role, featuring as a competitor in the Elsinore Grand Prix under the pseudonym of Harvey Mushman, as well as in the film’s memorable closing scene riding on a California beach with dirt-tracker Mert Lawwill and off-road legend Malcolm Smith.

The King of Cool’s time with us lasted just 50 years, as the Hollywood legend succumbed to cancer in 1980. But his legend lives on …

First Impressions

As mentioned in the intro, objectively reviewing the Scrambler is confounding. Like a cruiser, it is a slave to fashion. The headers of those cool-looking high pipes rub up against a rider’s leg, and the vintage-y dual shocks are lacking sufficient damping control. Its front tire squirms on longitudinal road seams, and its flat-as-an-ironing-board seat feels so very odd to an ass accustomed to modern, sculpted saddles.

But it surely looks like an authentic desert sled, subtly accented by the matte khaki paint color. It regularly draws in second glances by people who recognize Triumph’s rich heritage, even if they’re only casual observers.

“If I bought a bike, I’d buy a Triumph,” said one 40-ish passerby as I parked the Scrambler. “Or a Harley,” he added, which reveals the shallow depth of his motorcycle knowledge but gives an indication of how much pull the Triumph brand has maintained over the decades.

The Scrambler’s 32.5-inch seat height might be a stretch for some, and a right-leg’s direct reach for the ground is spoiled by the headers intruding on inner knee space. A right leg is constantly in contact with the headers’ shielding – short-pants riders beware! – but the guards do a commendable job of isolating radiant heat to several degrees shy of uncomfortably hot. The headers look like they could’ve been placed further inward but at the risk of heating up the fuel system’s throttle bodies.

Aside from the exhaust issue, the roomy rider ergonomics were judged to be quite agreeable by our test riders, no matter their size. The handlebar position demands more forward rotation than expected from an off-road-ish design, but it still yields an open rider triangle. Footpegs are located about where some of us would like to place their feet at a stop. Tall, period-looking round mirrors offer an unimpeded view rearward. Both hand levers are adjustable for reach.

Triumph’s 865cc Twin benefits from fuel injection, but it’s a step behind the latest systems. The throttle bodies have a pull-out knob for richening the fuel mixture during cold-weather starts, and throttle response can be a bit abrupt from closed throttle. Worse, our tester would occasionally exhibit a cough off idle when leaving stop lights.

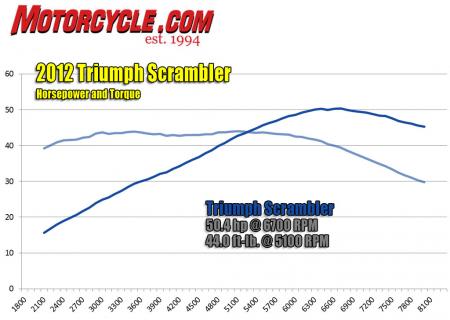

Although power can’t be called abundant, its flat torque curve and loping nature delivers adequate grunt unless you’re at a track or running from the law. Unlike many motorcycle engines, the Scrambler delivers power all the way throughout its rev range, so there’s no need to rev it out for adequate thrust. Its linear power delivery is especially evident when carting around a passenger, as it enables a rider to be ultra-smooth. The flat seat permits your pillion to comfortably snuggle up behind you.

The torque-rich powerplant enables easy getaways from a stop despite the clutch’s narrow and poorly defined engagement zone. A long first gear is handy around town, and the short-throw, 5-speed gearbox is a pleasure to row through. At first we wished for a sixth gear, but fifth proved to be just fine even at 80-mph cruising speeds.

With a fueled-up curb weight of 506 pounds, the Scrambler is by no means a lightweight, but it comports itself well in urban use despite a lazyish 27.8-degree rake and moderately lengthy 59.0-inch wheelbase. Its 19-inch front wheel creates a minor flop effect at parking-lot velocities, but low-speed turn-in response is pleasingly quick. However, the large (and heavy) front wheel slows responses at elevated speeds and during side-to-side transitions.

The Scrambler’s brakes are a massive upgrade from those on the Meriden-built Triumphs of yore. Although using just a single disc at both ends, the rotors are relatively huge at 310mm in front and 255mm at the rear, both clamped by two-piston Nissin calipers. Each provides a nicely firm lever feel. If there’s a fault, it’s that the rear is fairly easy to lock because of a large brake disc and low-grip tire.

Suspension is about what you’d expect from a modern interpretation of a classic. The 41mm Kayaba fork is non-adjustable but performs well enough over its 4.7 inches of travel. The period-looking dual Kayaba shocks out back exhibit a period-feeling lack of damping that can deliver a jouncy ride. Preload adjustability can accommodate various loads over 4.2 inches of travel.

Highway travel on the Scrambler is tolerable rather than exemplary. Its tallish bar positioning and lack of wind protection turns a rider into a human sail at elevated speeds, and longitudinal pavement grooves can influence a squirmy effect on the front tire that feels like (but probably isn’t) frame flex.

The engine’s mild tuning and power delivery results in fuel economy numbers that are higher than we typically get from our heavy throttle hands. It averaged nearly 45 mpg during its time with us, and we bet most riders will be able to eke out 50-plus mpg stints. With its 4.2-gallon tank, fuel stops can reach 200 miles apart.

We all appreciated the many vintage-y design elements of the Scrambler. Its tank is highlighted by the classic harmonica-style Triumph badge and old-school knee pads, and the bullet-shaped turn signal lamps made us feel nostalgic. We also felt nostalgic when we went looking for a helmet lock that doesn’t exist. “I can excuse not having a helmet lock on a lot of modern motorcycles, but such an item is requisite on a pseudo-vintage bike such as this,” Roderick flamed.

The high-mount exhaust system is reminiscent of something from the 1960s, and its unique design is visually impressive. However, 21st-century exhaust emissions regulations force it to be large and heavy. Anyone coveting stealth will appreciate its dulcet tones, but we believe it’s a little too nice for our ears. Roderick described it as sounding like a fart in a bathtub.

Conclusion

So, the Scrambler is a vexing proposition. It rates poorly if you’re a looking for the ultimate in performance for the dollar. However, the Scrambler also proved to be irresistible. It packs in an amount of coolness no modern design can achieve.

“The Scrambler certainly owns the look of the old-school scramblers of yore,” says Roderick. “Engine, braking and handling performance are all commensurate with the type bike the Scrambler represents. In other words, it's a modern bike whose looks and performance aren't much better than the models it meant to emulate. However, the chances of it breaking down and leaving you stranded are relatively remote. It’s a great blank canvas for a motivated enthusiast to manipulate into a one-off custom of his own design.”

So, if the allure of a vintage Triumph tugs at your heartstrings, you’re likely to be enthralled with the Scrambler. There is simple nothing else quite like it.

“It emits a Steve McQueen cool,” Roderick observes. “Just don't try jumping any barbed-wire fences with it.”

Related Reading

2012 Harley-Davidson Sportster SuperLow vs. Triumph America [Video]

McQueen v. Knievel Road Test

2009 Triumph Thruxton Review

2008 Naked Middleweight Comparison: Triumph Street Triple 675 vs. Aprilia SL750 Shiver

2007 Triumph Bonneville America Review

2007 Triumph Bonneville T100 Review

2002 Triumph Bonneville America Review

2000 Triumph Bonneville Review

All Things Triumph

More by Kevin Duke

Comments

Join the conversation