1999 Kawasaki Drifter 1500 - Motorcycle.com

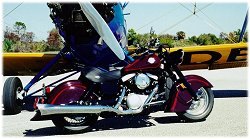

SOUTH BEACH, MIAMI March 1999 -- The bike you are gazing at is not what you think it is, but your confusion is just what its designers intended. What you are looking at is the 1999 Kawasaki Vulcan 1500 Drifter. What you are seeing is a late 1940's Indian Chief.

What you a looking at is SOHC, digitally fuel injected and water cooled. What you are seeing is side-valved, carbureted and air cooled. What you are looking at is Japanese. What you are seeing is quintessential Americana.

The Drifter is Kawasaki's latest heavyweight cruiser. It follows a decades-old design philosophy that started with their very first Vulcan 1500, a child of 1970's chopper stylings.

Next came the 1950's styled Vulcan Classic followed by the Nomad with its 1960's leanings. Seen in this light, the Drifter's 1940's image is a logical design result. And what better way to reflect the elegance of the era than by incorporating two deeply skirted fenders?

Long, sweeping, cromulent and curvaceous fenders that look positively ostentatious. Fenders that are however so large that they seem to overwhelm the rest of the bike, a fact that is enhanced by the almost complete lack of chrome.

Chrome that would help draw your eye to other elements of the motorcycle. There is more to this ride than its deep wheel wells. The first thing we noticed after thumbing the starter button was the new and much improved 1500cc Vulcan engine. To start with, the Drifter received the first digital fuel-injection Kawasaki has ever incorporated into one of their V-twin engines. Add a 9:1 compression pistons and dual plug ignition and your ride starts with a whopping claimed 85 ft-lbs of torque... at 2500 rpm!

Torque that will leave all other Vulcan owners crying. Why? Because there is no way to upgrade other Vulcan mills to the new system, one which also includes new pistons, dual spark plugs, a 6250 rpm rev limit, no petcock and digital fuel injection. By the way, there is also no "reserve tank." The only thing that lets you know you are about to run out of gas is a small, car-styled idiot light. Personally, we're partial to the large measure of safety a "reserve tank" offers. We don't care if it has a gas gauge or idiot lights, we'll still run it dry given half a chance! The water-cooled 1470cc engine is complemented with rubber mounts and a geared counter balancer. These facts, coupled with a short-stroke big-bore design creates an incredibly smooth V-twin. Almost no vibration gets through the handlebar or floorboards. This can be seen as good or bad, depending upon how you like to feel your cubic inches. Getting all this technology to the pavement is a slick transmission that offers not one but two overdrives! This translates to a smooth 90 mph cruiser and an easily verifiable 115 mph indicated top speed as well as a 5th gear that demands you go at least 65mph if you want to think about accelerating.

"The tranny is smooth and its hydraulic clutch is a breeze. After the transmission has had its way with the engine power, that power is sent to the rear wheel via a shaft drive.

The best thing about a "World Introduction" is its exotic locale, the worst is limited seat time. To showcase this engine and motorcycle, Kawasaki chose South Beach Miami for the Drifter's World Press Introduction: An area that boasts more than a few cruising boulevards and plenty of flat, high-speed highways.

In-town cruising revealed the beauty of its mega-torque mill. What gear are you in? Who cares! Flat superslab cruising revealed a new chassis that is rock solid all the way up to top speed.

The suspension is super soft, but backed with decent dampening. Hard blips of the throttle jump the center of the bike up several inches. The rear shocks are air assisted and offer a five-position dampening selector. A hand pump should be standard on next year's bike to modulate air pressure. With a 15 psi peak in each shock, Kawasaki doesn't want anyone getting any clever ideas about using a gas station air pump. We can't report on the Drifter's handling through curves, because Florida doesn't have any!

Curiously Kawasaki chose not to go with hidden rear suspension on the big 1500 Drifter. Perhaps because that style of suspension generally limits performance and comfort. The 800 Drifters, destined for Europe and Japan only, will offer hidden rear suspension.

For reference, the Indian Chief came with a strange looking "plunger rear suspension unit." The rear wheel was mounted in the center of an enclosed shock, which connected the top and bottom tubes of the chassis.

THE WAR IS OVER..."When the modern cruiser era began in earnest, so did the battle over the right to slap the old Indian logo on the tank of a modern bike."

America's war with the Indian has finally ended... and the Japanese have won. No, we aren't talking about Native Americans, or even East Indians. We are of course referring to the long defunct American Motocycle manufacture by that name.

When the modern cruiser era began in earnest, so did the battle over the right to slap the old Indian logo on the tank of a modern bike. Unfortunately this immediately led to 1990's reverse-design philosophy; where the concept is to first and foremost own an image in order start making money off of licensing fees for lots of "lifestyle" accessories -- jackets, shirts, Cafés, etc. Then you may start thinking about cobbling together a bike. In this case one that looks something like an old Indian Chief.

Of course, the proper approach from an enthusiast's point of view is to design an exciting and sound motorcycle, backed up with concepts like p parts lists, service manuals, factory trained mechanics, not to mention a factory filled with metal cutting equipment, skilled labor and an engineering staff. Then and only then do you start deciding on a great name for the bike.

The recent court decision may have awarded California Motorcycle Company the rights to the coveted monicker, but Kawasaki has gone ahead and put the horse in front of the cart and designed a great, functional, reliable motorcycle. One that looks just like an old Indian Chief. One that was designed by real engineers, not greedy marketers. One that is not a name plate held off the ground by yet another knock-off Evolution engine bolted into yet another knock-off Softail frame. One that stands on its own engineering merits, not others.

Remember that old anti-litter commercial in the 70's where the Native American guy is crying? We think that works here as well. This is truly a sad end to a venerable old American icon. Not sad for what Kawasaki has done (which may have helped save the Indian trademark from degenerating into junky nostalgia fit only for highway tourist traps), but sad for what short-sighted greed has kept others from doing properly.

Brake performance is what you would expect -- solid but not awe inspiring. Kawasaki made a point of drawing attention to the two solid disc brakes on the Drifter. All we noticed was that they are quieter than standard drilled discs.

The exhaust note is excellent. A bit too quiet for our tastes, but a nice low rumble nonetheless. It should be very interesting to see what the aftermarket industry comes up with for the Drifter for a couple reasons. First of all, the entrance to and the exit from the accumulator has no less than three 90° pipe bends. This can't be doing engine power any favors. A standard straight 2-into-1 joint may help unleash even more power from this capable engine. However, the stock exhaust sound is quite nice. What will the removal of the accumulator reveal?

While the stock exhaust may raise some questions, the stock ergonomics do not. Your feet and hands have never been treated so well. The wide, pull-back handlebar is a dream. It lands the hand controls at a perfect level and angle for a motorcycle of this demeanor. The floorboards are also perfectly positioned and offer one of the best heal-toe gear shifters in the industry, the heal portion of which is behind and level with the floorboard. It is perfect for stomping into a sometimes difficult second gear.

One detraction from complete comfort is the stock seat. Not only is it a visual atrocity, but it is also too soft and covered with sticky, stretched vinyl. Ugh. Luckily the available solo seat both looks and feels much better. Now if Kawasaki or the aftermarket would just produce one loaded with fringe, if for no other reason than to complete the classic Indian Chief look.

The bike's visual queues are all there until you get to the stock, two-up seat. Demographics no doubt demanded that the bike be capable of carrying two riders, but this seat defies any sense of traditional aesthetics. The thing is, well, slightly visually challenged.

Some of this can be blamed on the design of the rear fender. The rear fender is attached to the swingarm, and this requires that the distance between the seat and the fender to equal the rear wheel travel, which means the seat sticks up. Fringe hanging down off a seat would help to close that awkward gap.

It doesn't stop there. The fender design also creates a very strange visual effect and a unique dilemma. First the strange visual effect, which has to be seen to be fully understood. We'll try to explain ... A standard cruiser has the seat attached to the fender and allows the wheel to rise and fall while leaving the seat, fender and rider level. The Drifter's seat is attached to the frame (as are sport bike seats). Its fender is attached to the swingarm. This means that as the rear wheel falls with the road, and because the fenders are so prominent, so does a very large and noticeable portion of the bike, creating the illusion that the rear end of the bike is drawing up under the motorcycle. The effect can most easily be imagined by thinking of an inchworm. The center of the bike appears to rise, as the front and rear of the bike stays on the ground.

The unique dilemma is less difficult to explain. Actually, it is quite simple. Where do you mount saddlebags? They can not be attached to the giant rear fender for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that the rear fender, like the front, is plastic. That leaves only the seat. More likely a replacement seat that exercises more creativity than the stock one.

Creativity is something that at times is ingeniously flashed all over this bike, but at times seemly absent in other areas. For example, to generate the proper power and sound characteristics for this bike, a large exhaust accumulator is cleverly hidden behind a heat shield that gives the appearance of a two-into-one exhaust pipe junction. However, on the opposite side of the bike, a voltage regulator is unimaginatively hung out in the open under the shaft drive for all to see and a device designed to dissipate heat is mounted adjacent to a hot exhaust accumulator.

Creativity is exercised superbly on the design of the gas tank. The tank-mounted speedometer is a work of art, bold and beautiful. Just what the doctor ordered. The tank badges are also beautifully done, boastfully proclaiming the bike's name. Yet right underneath these accomplishments, a powerful 90 cubic inch engine is left looking bland and downright frumpy when compared to other modern cruisers. While this may accurately represent the unassuming looking 1947 Indian Chief engine, we feel it does nothing to enhance the look of a cruiser that has to make a living in 1999.

In the end this is a bike that passes all the logical tests. A bike that isn't what you thought it was, but is everything you would want the real thing to be. From its tombstone tail light to its black-bullet headlamp, the Drifter is a visual feast. Mechanically it is a comfortable and powerful companion. Unfortunately, even given all this, for some it falls slightly short in the most crucial test for this genre: the undefinable, intangible and admittedly arbitrary test of passion.

"The Drifter has the look of a beautiful old bike."

A bike that has lived in people's memories for 50 years. One that people rebuild and restore with loving and obsessive dedication. But the Drifter isn't that motorcycle. It is better in a hundred, maybe in most every way, but it is not an authentic article. Therefore it does not exude an innate sense of value. This is unfortunate, because with a few relatively minor changes, this could become a bike that inspires devotion.

To start with, all the plastic covers have to go. If it doesn't function, don't put it on the bike. A bike of this class should be as genuine as possible. At least Kawasaki should offer metal and chrome covers as an manufacturer's option. What might work in a design-by-committee board room doesn't work on the street. Next, add a few more chrome touches or options. While heavy chrome accents are quickly becoming a cliche, some strategically placed chrome -- perhaps the engine guard and handlebars -- will help draw the eye away from the prominent fenders and more toward the bike as a whole. Finally, try to showcase the engine! It is strong and confident, why does it look like Elmer Fudd?

The fenders are a bit more problematic. On one hand purists will demand that they must be real. Metal, that is. Purists do have a point: There is something a bit more authentic, more traditional about metal fenders. Perhaps one reason, among many, why cruisers are so popular in America is that they make a link, albeit a somewhat tenuous link, to a past when we actually produced and exported things like cars and steel rather than video games and movies. Plastic, (so derided in the culture than "plastic" is often synonymous with "phony") for some, breaks this thin link. Painted carbon fiber has been suggested but it still wouldn't satisfy the traditionalists. Also, carbon fiber is expensive and has yet to make any impact outside the sport-performance categories.

Yet metal fenders create a number a problems. First, you would no longer have a bike that costs $11,500. Next, and in our minds more importantly, we're guessing that metal fenders this large could add 30-pounds or more in unsprung weight and most likely screw up the Drifter's otherwise excellent handling and performance characteristics. Aluminum fenders might be an option but they are still heavier than plastic more expensive and because their surface area is so large they will attract more road debris that cause pits and dents. We suspect that unlike a few American custom owners -- who own the bikes primarily as fashion accessories, trailering them to Daytona and Sturgis and riding mainly to the nearest custom bike show or waterhole -- Vulcan owners ride their bikes, often and hard. The big Kawasaki Vulcans are perhaps the lightest handling big-bore cruisers made. Large metal fenders may upset the geometry, stress the suspension and affect handling. True, you would then have an authentic piece of Americana with an interesting modern global spin, a bike people would want to own forever and even pass down to their children. But would they want to ride them?

More by Motorcycle Online Staff

Comments

Join the conversation