Taking a Peek Behind the Crimson Curtain

An inside look at the Ducati Design Center

As all projects do, the new Ducati Diavel started with an idea. The 2019 Ducati Diavel wouldn’t be an entirely new motorcycle as it was when the idea hit the drawing board in 2008 – later being released in 2010 as a 2011 model – but rather a new generation of the machine. This is why we found ourselves seated in the boardroom in which Claudio Domenicali himself and the board of Directors for Ducati Motor Holding meet each morning, where decisions of the utmost importance are made for the Italian marque.

Stefano Tarabusi, Ducati Product Manager for more than half of the current model lineup, would lead us through the design process of how an idea at Ducati goes from a blank sheet of paper to rolling off the end of the production line amongst a whirlwind of fanfare and likely a shower of champagne from Domenicali, to celebrate the first of a new model produced.

Keeping it Brief

The product brief contains all of the information about a bike that doesn’t exist yet. This includes all of the ideas, technical features, and performance Ducati wants out of the motorcycle. Not only does it include what Ducati hopes to build, but also data from the world outside in the way of the market, the competitors, and the customers. One key element of the product brief is the design brief, which contains all of the guidelines for the design of the new bike.

The product brief itself can be started a few different ways. It can be market-driven if it is decided that there is an opportunity in the market, then it will be focused on satisfying this opportunity. There are also customer-driven product briefs, where the company may see unmet customer needs and puts together a product defined by these needs. There is also a position-driven brief, something that comes when the position of the motorcycle in the market is already established, perhaps in the instance of a “facelift” as Ducati calls it, or a refresh of graphics or other minor changes.

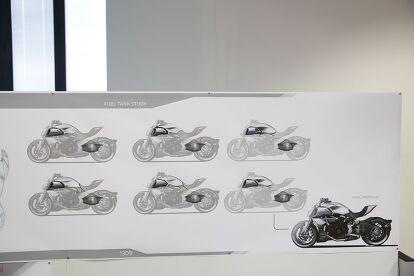

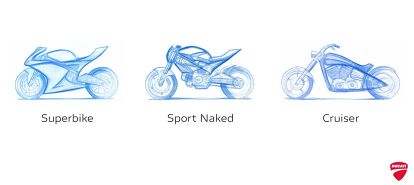

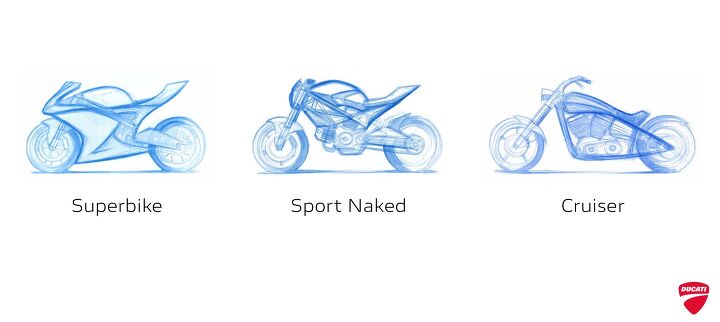

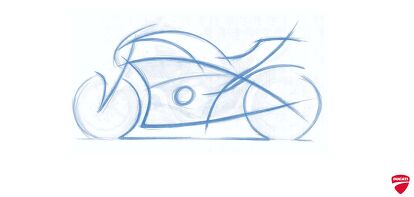

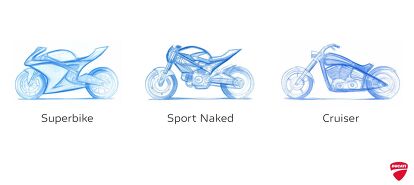

Sometimes when looking to build an entirely new model, as was the case with the Diavel, the design brief can drive the entire product brief. The team codenamed the new motorcycle “MegaMonster”, which in itself describes the type of motorcycle Ducati was looking to develop. It wanted a sport naked, but on steroids, a bigger stronger, more muscular and more aggressive Monster. Eventually, it would be decided that the MegaMonster would be a blend of three motorcycles: the sport naked, the superbike, and a cruiser.

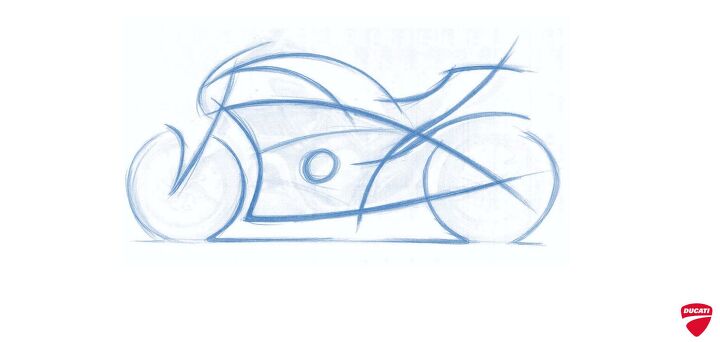

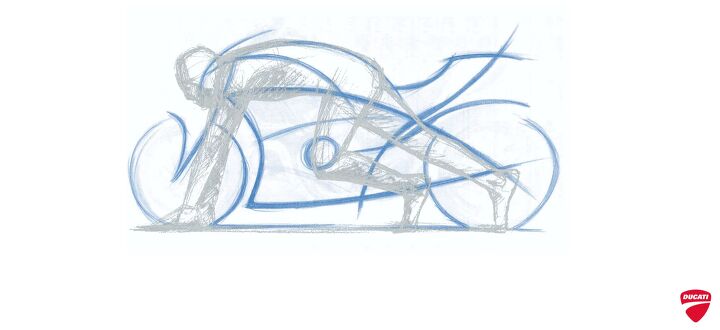

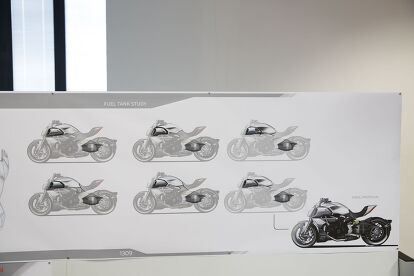

The new motorcycle would use elements from all three of the aforementioned motorcycle types to develop an entirely new segment for Ducati. From the sport naked, the forward-weighted stance, visible frame and engine, and high slim tail section. From the superbike, the side and belly fairing, as well as a sharp and high tail section. Lastly, from the cruiser, a distinct line from the handlebar to rear wheel and from the front wheel to rear wheel as well as the low seat height. When sketches of these three motorcycle style are overlaid, the shape of a sprinter lined up at the starting blocks can be seen, most of the mass in the front with a sloped back to an extended tail. This would be the underlying shape of the Diavel.

For the new Ducati Diavel 1260, this concept was kept. The design brief of the original Diavel was kept for the foundation of the new Diavel 1260 with obvious updates in terms of modernity and more contemporary design as well as other new elements. Moving to the Ducati Design Studio we would have the opportunity to follow the Diavel 1260’s path from this point to a finished production motorcycle.

Ducati Centro Stile

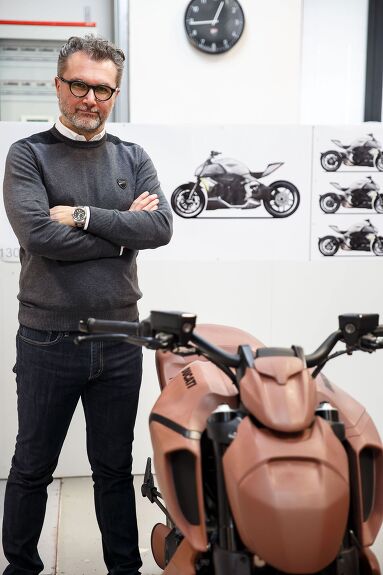

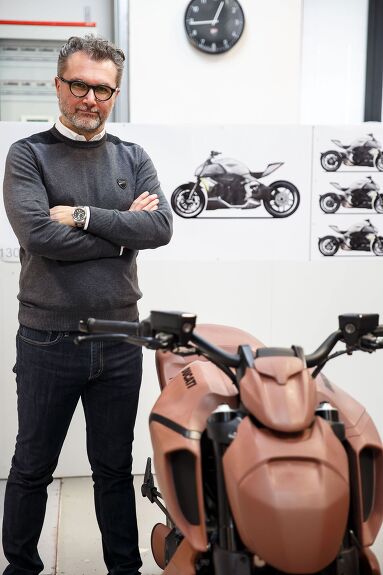

The Ducati Design Center located in the Borgo Panigale factory is made up of 20 individuals – 30 including the clothing design and accessory departments. Everything related to creativity is done here. There are no freelancers, designs firms, or otherwise outside entities contributing to the creative development at Ducati. The design center has six designers – three senior and three junior. Andrea Ferraresi, Ducati Design Center Director, brought us behind the big white door to explain what goes on throughout this phase of development.

Andrea has been with Ducati for 19 years, first in research and development, and now heads up the design center working to establish an imperative bridge between the designers and engineers. Andrea’s background and schooling are both in engineering, allowing him to better understand both sides of the process. Ferraresi pointedly notes, “I think that one of the secrets that we have of our bikes is very, very good cooperation between our designers and engineers since the very first day we start developing the bike.” Andrea mentioned, prior to 2004, it was not this way. There was a constant struggle between the two departments that made working together to find solutions difficult.

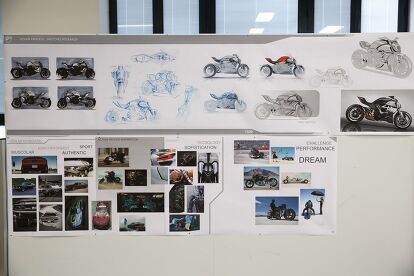

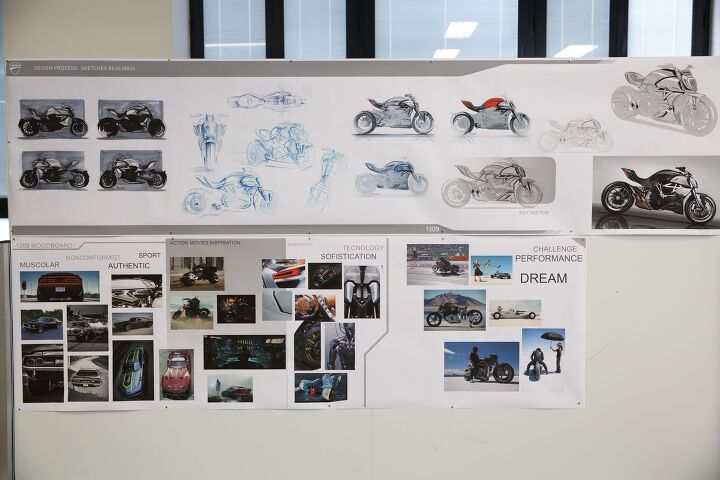

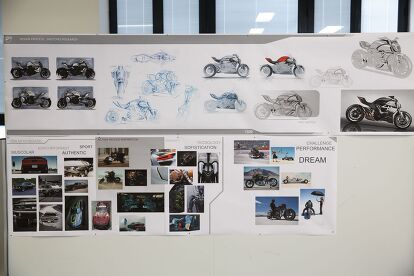

Looking at the Diavel 1260, designer Giovanni Antonacci was the design coordinator behind this project and would give us the up-close snapshot of what the process entails. Beginning with white paper is key for all of the designers at Ducati. They all use digital tablets further into the process, however to get started they prefer a clean sheet of white paper to begin their sketch. Prior to even sketching though, the designer puts together a mood board. “The mood board for us is very important,” says Antonacci “this is the inspiration for us. With the mood board, we can understand the feeling the bike must have, the feeling, the concept, and especially the direction the vehicle must take.” The mood board we were shown was plastered with American muscle cars showcasing the muscular performance-focused character with shots from movies such as Batman, Wolverine, and Iron Man to give a feeling of the action one should feel from the bike and also close-up images of tech and high-end cars to drive the feeling of sophistication and modernity. Finally, images of what Antonacci calls the dream, racing competitions, and bikes situated on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Andrea chimes in to remind us that there are three very romantic moments for the designer: the organization of the mood board in order to inspire the drawing, the clay model where the designer finally gets to feel the bike and even mold it himself, and the moment the designer sees the motorcycle traveling down the road.

Once the designer works to revise his or her sketches, taking note of proportions and exploring different proposals, the key sketch is worked out. This means the direction is correct, the proportions are correct, and that the sketch respects the design brief. The next step is the final sketch which is then worked out in Photoshop. The entire process has taken one to two months at this point.

The designer whose sketch will ultimately be used for the design of the bike is decided by a group of people – a sort of internal marketing research team – and also the design director and Domenicali himself. This is set up as a competition. If the project is important and the other designers aren’t busy, it’s possible six design proposals will be submitted, which was the case with the Panigale V4. The designs are then reduced to three, two and then one, the final winner of the competition who goes on to complete the project.

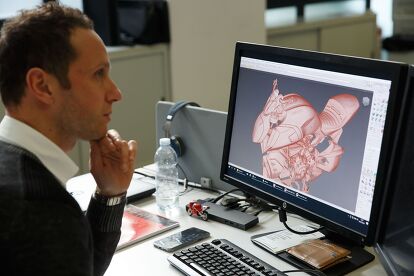

Simultaneously, the prototype department and design department work to create the first 3-D models of the bike. The design department uses a CAD to mill the model out of foam while the prototype department begins test riding the model to see if they find any issues with the tank, seat size, and generally any problems that may need to be rehashed after riding the motorcycle. Taking into account the feedback from the tester, the design team modifies the design.

This process is only to understand from 20 feet away whether the proportions are correct and if the concept functions. This pre-clay foam model is a rough realization of the designer’s sketch and is not meant to be closely scrutinized but rather looked at in a macro view.

Up to this point, the competition is ongoing; two final participants and two pre-clay or foam models will be milled to see if the design leaps from the 2-D world well into 3-D. It is at this point the winner is chosen to continue. “Once the design has been chosen, the real works starts,” says Ferraresi.

Sculpting Into Reality

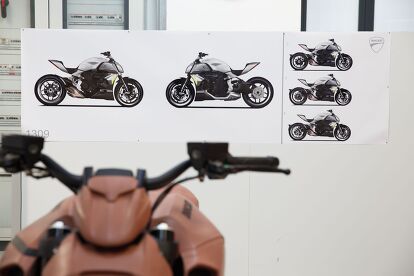

“Personally, for me, it’s the favorite stage,” says Antonacci as we walk over to the clay model, “With clay the designer has the possibility to explore the style and the details”. Once the pre-clay foam model has been scrutinized, the clay process begins in order to fine tune the style and detail.

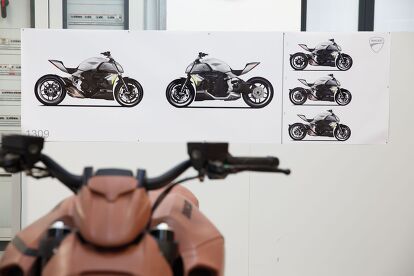

Throughout this process, the engineers have been developing a technical base as Ducati calls it. The base includes everything seen in these pictures aside from the clay bits. The frame, engine, wheelbase, seat height, etc is all more or less set at this point. Some ergonomics can be changed, though the staff tries to have everything pretty well buttoned up at this point from a technical standpoint.

The clay pieces are developed from CAD files and milled similarly to the foam, then brought and put onto the motorcycle in the design center. These are rough castings and require refinement to elicit the smooth detail seen in these pictures.

“The designer loves this phase, the romantic phase, for two reasons mainly,” says Andrea Ferraresi, “Because they touch the bike and can model the bike by themselves and because it’s extremely flexible so they can try and test and experiment with even big changes in one morning or one day. In a night, you can completely change the bike with two or three sculptors. It’s very, very flexible.”

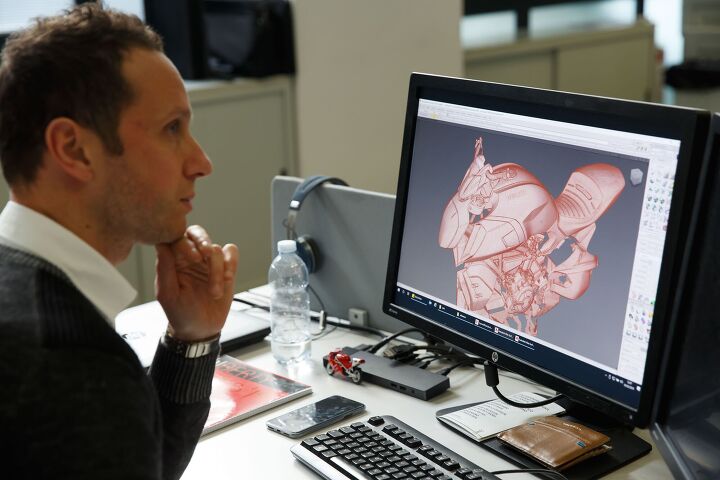

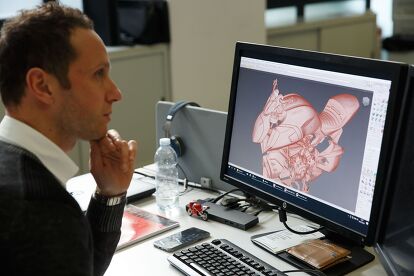

When the bike is in this stage it is scanned often. Ducati uses a program and scanning technology called Point Cloud to take 3-D scans of the clay in order to document and save the changes that have been made throughout the process. This process requires thousands or more small black dots all over the motorcycle which make up the 3-D image in the program. This allows designers to look back after changes are made and to give them the possibility of previous starting points. During this portion of the process the internal focus group is checking in on design. Ferraresi says this is perhaps the most important part in which the panel can give feedback because it is still easy enough to make changes.

Once the clay model is finalized and Claudio Domenicali has given the stamp of approval, the design is frozen. No other modifications will be made unless they are necessary such as a road tester saying a particular edge or something else is uncomfortable. Now it is time to start thinking about production and the tooling to manufacture the parts on a large scale. The basis for this is developed using the Point Cloud scan of the clay model.

Back to Digital

“Reverse engineering the scan for building and tooling parts is by far the most expensive part of the phases we have seen this morning,” says Andrea. This can mean four or five guys working together putting in ten hour days for many weeks. During this phase, ideally, everything is set and the team hopes the test riders do not come back with any issues. Unfortunately, sometimes these things happen. Ferraresi tells us if the test rider comes back and says the seat is 10mm too close or maybe an edge is too sharp, the changes can be made on the computer, however, if the seat needs to come back 40mm or there is another large drastic change that needs to be made, they will go back to the clay in order to make the revision and rescan the updated design.

The team uses virtual reality in two different ways during this phase. First, it is used to check the quality of the surfaces, and second to simulate different colors on various components. Once this has been done the team moves toward using this final CAD to mill the final foam model.

This finished model has every single detail in place and is presented to upper management for final approval. After approval, the model still receives a lot of use. This final model is meant to look just like the finished motorcycle from six feet away. These models end up traveling the world for display in trade shows as well as being used when considering different finishes, colors, and graphic details. During this stage the team then creates another mood board for inspiration for the finishes.

The challenge, which is ever-present to the designer, is to maintain focus of the original sketch. When the pre-production working prototype rolls into the design center, the designer can finally be happy if the clay and pre-production model closely follows the final sketch. It is a difficult process we are told and easy to lose sight of the original vision.

The Third Romantic Stage

Ducati Design Coordinator, Giovanni Antonacci, has yet to realize this third stage as the Diavel 1260 is just now hitting the production line, but you can imagine the impact of seeing your baby, as it were, rolling down the road being enjoyed by motorcyclists around the world. The satisfaction this brings is worth all of the effort we’re told.

Having been taken through this process based around the Diavel 1260 gives one a greater appreciation for the finished product. It’s easy to look at a motorcycle and critique small things here or there. However, once you have been shown the process, met the people, and have even a modicum of knowledge of the time and amount of people that touch a project like building a new motorcycle, you can truly appreciate what it is to develop a Ducati motorcycle from a sheet of white paper, to a rolling rumbling Italian work of art.

Ryan’s time in the motorcycle industry has revolved around sales and marketing prior to landing a gig at Motorcycle.com. An avid motorcyclist, interested in all shapes, sizes, and colors of motorized two-wheeled vehicles, Ryan brings a young, passionate enthusiasm to the digital pages of MO.

More by Ryan Adams

Comments

Join the conversation

A very detailed description of the Ducati design process. I imagine most of the big manufacturers follow something similar, but to see Ducati using 'mood boards' to inspire design seems like a big switch from a time when it was an engineer's personal vision that drove creation of something like the 916. Of course, personal vision can miss the public's mood sometimes in a big way - witness Terblanche's 999, so maybe the process described is the only acceptable-risk way to a successful model these days.

Having spent over 30 years at GM, some of which was as Product Manager for various Pontiac carlines, the process detailed here is quite similar, if not identical, to that used to develop automobiles, including the "mood boards'.