Tomfoolery - Respecting The African American Motorcyclist

In the build-up to our nation’s observance of Martin Luther King Jr., it became apparent that I’d heard nothing more than audio highlights of the Dr.’s speeches. For shame, to never have listened to an alocution in its entirety from one of last century’s greatest orators. Youtube easily rectifies the oversight, and I urge anyone who’s also lacking the experience to listen/watch. His famous “I Have a Dream” speech lasts only 16 minutes.

Martin Luther King – I Have A Dream Speech – August 28, 1963

One click leads to another – such is the internet – and next, I’m staring at the homepage for African American History Month, which begins February 1st. Well, then, thought I, what better time to honor the trials and tribulations of Black History and MLK than by extolling the accomplishments of African American motorcyclists – many of which, at least present day accomplishments, would be questionably attainable were it not for the efforts of MLK.

“As women of color, there were times we weren’t allowed to ride,” said founder of Black Girls Ride magazine, Porsche Taylor, in an article by the Daily Breeze, about the large MLK day tribute in Inglewood, California. “So, to be able to come out on a sunny day and ride for peace and in honor of Dr. King is great.”

In 2000, the AMA created the Bessie Stringfield Award, and presents it to individuals who have been instrumental in bringing emerging markets into the world of motorcycling. Past winners include:

- Scot Harden – 2014

- Mark-Hans Richer – 2013

- Gabrielle Giffords – 2012

- Margaret Wilson – 2003

- Rita Coombs – 2002

- Patti Carpenter – 2000

Later in life, Stringfield was found to have an enlarged heart, but when her doctor said to stop riding, she answered, “If I don’t ride, I won’t live long.” She never quit until her death in 1993. You can learn more about Stringfield and other influential woman in the book Hear Me Roar: Women, Motorcycle and the Rapture of the Road, by Ann Ferrar.

Johnson is also known for achieving another first. By claiming to be American Indian, Johnson was given license to compete in national AMA motorcycle races during a time when the events were segregated. In 1932, Johnson was challenged by an AMA official at an event barring “colored” riders. Producing his AMA membership card, there was nothing the AMA official could do but let Johnson compete, then watch as he won the race.

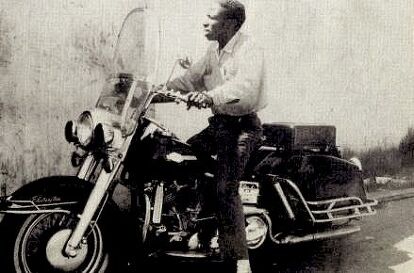

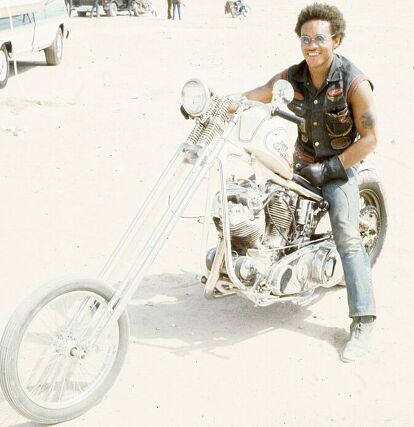

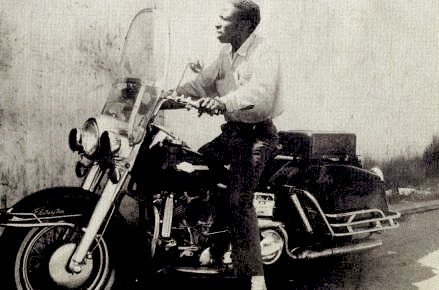

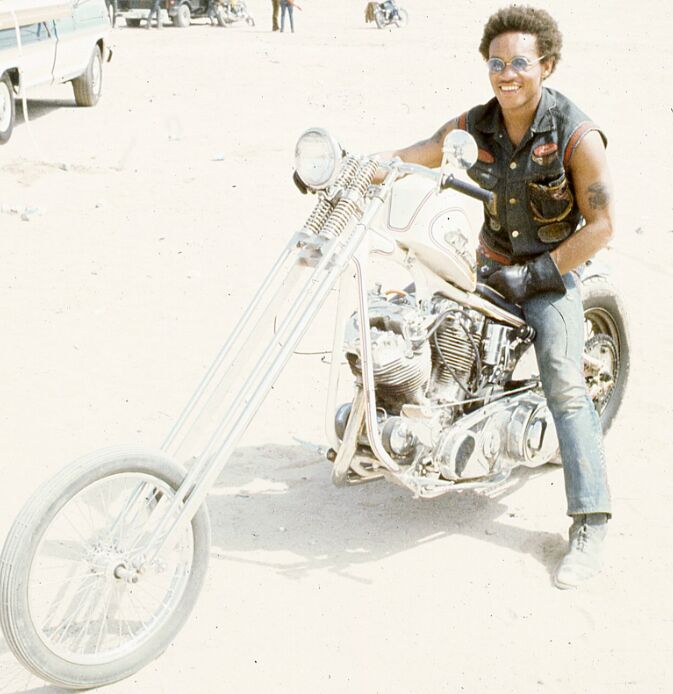

Flash forward to the era of the Civil Rights Movement and the advent of the film classic, Easy Rider. Although the movie explores countercultural hot topics of the 1960s, there are no scenes depicting the racial hypocrisy of the time. The absence is never more ironic than in the design and construction of the two famous choppers upon which the movie’s protagonists rode: Captain America and Billy’s Bike.

“The Easy Rider motorcycles were designed and built by me in my backyard. My longtime friend and mentor Mr. Ben Hardy assisted me wholeheartedly,” says Vaughs in an interview on The Vintagent – which provides fantastic insight into Vaughs’ world as well as the Easy Rider movie.

Another leap forward and we’re in the modern age. African American motorcyclists, some famous, many not, abound. Unlike Hardy and Vaughs, there are no sweeping the famous ones outta sight. Nowadays, the skills of black motorcyclists, such as James Stewart, Jason Britton and Rickey Gadson are celebrated with the same vigor as that of their caucasian counterparts. Their posters adorn the walls of both black and white children as heroes of motorsport.

On the heels of Jeremy “Showtime” McGrath and Ricky “the GOAT” Carmichael rides James “Bubba” Stewart. Not only a SX/MX superstar, but the first black superstar in the history of the sport. He won 28 out of 31 125cc Nationals he raced, shares the only perfect 24-0 record in the 450cc MX outdoor season with Carmichael, is currently second behind Carmichael in outdoor National wins, and second behind McGrath in number of SX wins. Stewart also introduced the Bubba Scrub, an innovative jumping technique now in use by all motocrossers. His legacy is secure, and he’s certainly set a high bar for the next African American Supercross superstar.

Jason Britton and his No Limits extreme entertainment team have been stunting up the scene for years. His is the story of a childhood motorcyclist and UPS delivery driver turned international stunter superstar, Hollywood stunt double (Biker Boyz, Torque), and television host for the show Superbikes. He’s also a family role model with a lovely wife and three adorable children, who must salivate the thought of Bring Your Father To School Day.

From illegal street racer to the winningest racer in the history of AMA drag racing, Rickey Gadson is fast, fast, fast. He’s also smart, as the owner operator of the Rickey Gadson Drag Racing School and the Drag Racing Editor for Sportbikes Inc magazine. Recently, he traveled to Japan to consult with Kawasaki on the development of the supercharged H2/H2R. You can read about his experience in an interview our Chief Editor conducted with Gadson about the experience.

Riding Kawasaki’s Supercharged Ninja H2/H2R: Rickey Gadson Interview + Video

I know, there are more African American motorcyclists deserving recognition. If you’d like to give a shout out to anyone in particular, shout it in the Comments section below.

A former Motorcycle.com staffer who has gone on to greener pastures, Tom Roderick still can't get the motorcycle bug out of his system. And honestly, we still miss having him around. Tom is now a regular freelance writer and tester for Motorcycle.com when his schedule allows, and his experience, riding ability, writing talent, and quick wit are still a joy to have – even if we don't get to experience it as much as we used to.

More by Tom Roderick

Comments

Join the conversation

Thanks for all the positive feedback, guys. Can't promise all my future stuff will be as poignant, but I'll try.

Nice article. And thank you for the reference to modern-day

riders. I have known Rickey Gadson for many years, the passion he places in his

successful motorcycle drag racing career is on par with many of the great names

from other racing disciplines.