The Clay Modeler Bringing Motorcycle Designs To Life - Part 2

Delving into the future with virtual reality

In Part 1 of our interview with Nick Graveley, we discussed who he is, how he got started in clay modeling, and how he goes about his work. In talking with Graveley, his enthusiasm for the job was infectious, and the conversation naturally flowed, going a lot longer than we initially anticipated.

The original plan was not for the interview to be broken up into two parts, but after answering my initial questions, Nick inevitably steered the conversation towards virtual reality and how it is redefining what he does. So animated was he towards VR that he started to get goosebumps talking about it. When someone is that excited about a topic, it’s only right to give it its own separate story. And that’s exactly what we’ve done. Here, Graveley dives deeper into VR and what it means for the industry. After that, we look towards the future, get a closer look at his process, talk about beautiful design, and end with a look towards the future. Enjoy.

You mentioned VR (Virtual Reality) a few times. Tell me more about it.

NG: It’s insane. I remember the first time. I was like, this is amazing. This is just absolutely going to change everything. It was actually when I was at Zero two and a half years ago doing the SR/F. We scanned in the clay I was working on and overlaid it onto the latest engineering package, which was then all rendered in VRED, and we could look at it in VR. It gives me goosebumps just remembering it.

Now, there is VR modeling software that is good enough that I can actually start using it as part of my workflow.

What does VR allow you to do?

NG: As we spoke about before, often before I get involved with a project there has been a sketch signed off for development, and then a poly model is done which is then milled out of clay. If I’ve not been responsible for the model build-up, that’s when I come in and get to work.

Part of the reason why current digital concept modeling is so limiting is because you’re still just sitting looking at the model on a computer screen. It’s so difficult to appreciate the true scale. It means that what gets milled out of clay is actually, more often than not, not terribly useful.

I’m using VR now to take charge of the poly modeling phase myself and apply all my experience in physical modeling to that early concept model stage. Doing this cuts clay development time by maximizing the quality of output from that first modeling phase.

When you work in VR, you’re literally stood next to the bike at full scale. You can flip the bike over and zoom in to work on details as in any CAD system, but in the end, what’s important is how it looks at true 1:1 scale. Seeing it on the floor next to you is so powerful. Not just that, you can see the surfaces are fully rendered. They look painted, basically.

This is really cool to be able to see the way the surface will develop or change as it goes around a corner. You get an appreciation of light and dark, in a way that you don’t get in matte brown clay. You get part of it in clay, but it’s not as stark as what you see in VR. In clay, you have the advantage that you can physically feel it which is so important to fine-tune a surface, but let’s not forget, we’re talking about early concept modeling here, where the goal is to try things out, to move things around quickly and to get to a good starting point for clay. So, I don’t see it ever replacing clay, but it’s certainly an amazing addition to my tool kit.

Everything you’ve said so far is done before any clay is touched?

NG: Yes, that’s where I see VR coming in. That’s where I see VR being useful. It’s the most effective way that I’ve ever experienced of getting a sketch from 2D paper into a 3D object, and fast, too!

I don’t know how things will develop in the future, but companies are constantly trying to do more for less money, more quickly, and that’s just the way it goes. In cars especially, VR is starting to be used more and they’re doing a lot of digital development work before they mill out clay for verification. It seems to me that many automotive clay modelers have unfortunately been relegated to loading up clay onto the model buck, milling out the car, and then cleaning up the milling marks by hand – it sounds like a soul-destroying existence to me! I understand why they would think that OEMs don’t value the clay process anymore, but frankly, they’re just not moving with the times. It’s a bit like taxi drivers and Uber – A new technology has come along that supersedes the old model. You have two options – bitch and moan, or pivot and embrace the new possibilities. I prefer the latter.

Thankfully, I don’t see digital taking over motorcycles in quite the same way because they are a much more complex balance of mechanical and styling components that humans of different sizes have to interact with. Because of this complexity, it means there will always be a need for a physical model where the design can be fine-tuned.

To me, it sounds like the VR portion of it drastically reduces the amount of guesswork with the clay?

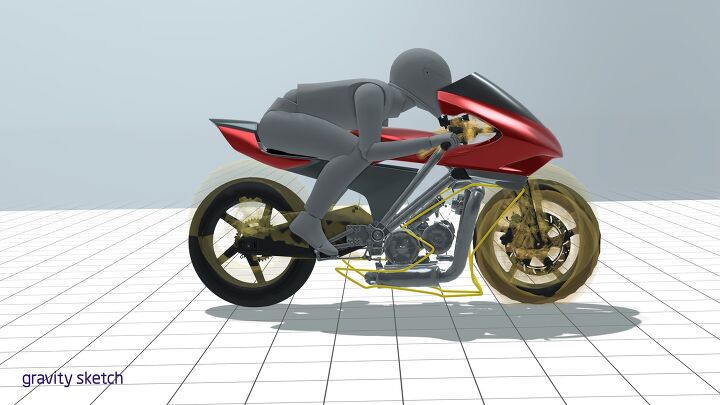

NG: Yes. I think it does. It’s very quick to try out ideas and see if those ideas translate well into 3D. One of several passion projects I’m working on is the Hypermono by Chris Cosentino of Cosentino Engineering. He’s designing and building a single-cylinder road racing motorcycle from the ground up, kind of reminiscent of John Britten, and I’m helping with the bodywork using VR based around his CAD files. Since I’m the designer on that project, I find it amazing how quickly I can try out ideas in VR. I tend to think in 3D better than 2D, so from only a very rough sketch we started out down a kind of heavily faired retro racebike path, before ultimately doing a complete 180 and pursuing a more modern look. The speed at which we could do this was quite amazing. You are developing a lot of ideas on the fly, and the Gravity Sketch software allows us to very quickly sketch in the idea to see if it’s worth pursuing and, if not, to easily revert to the earlier condition or just try something else.

Through trying out more solutions, we get to see what works and doesn’t work, which helps us hone in on a solution that works well. It’s a downfall of clay that the time and effort required to make a change is sometimes a barrier to seeking out better solutions. If you have something that is “ok”, then it’s tempting to leave it, rather than to destroy it looking for something that may or may not work better. Building a clay model is not the cheapest endeavor, so when you can try it quickly in digital and you can see it so realistically [it cuts down on time and cost]. Plus, it’s just so f*cking cool!

Especially during COVID, remote working is necessary. I’m working now with another forward-thinking client, KSR near Vienna, to develop some motorcycles. What’s cool is we can actually get in the same virtual room together around the model, to talk about the thing. They’re in Vienna, the designer is in Graz, and I’m in Munich. To potentially be able to work simultaneously with several clients that are dotted all over the world, that’s huge.

How much guidance/free rein do you have? Is someone looking over your shoulder?

NG: Yes and no. I would say that even though I’m not “working as a designer” now, I get to do as much design problem-solving now as I always did, maybe even more so. Because every single surface I’m making is like that to solve a certain design problem, whether we’re clearing a component, how it meets an adjacent surface, and how those surfaces need to be the right proportions when seen next to each other. So yes, in that sense I’m doing very localized design work because I’m having to make many of these decisions. I’ll also give other input, but I try hard not to overstep. I never want to be seen as trying to lead the design, because I think if I work with a designer and he feels like I took over and didn’t let him be the designer, then I’ll never get asked back again.

Also, it depends on the designer really. Some designers are very clear about what they want, and that’s great. I’m very happy to work with those guys and have those clear instructions and those clear visions. There are guys who are really experienced and know exactly, pull this up two mm, put more crown here, whatever. That’s fine. That’s actually really great because you know you’re both speaking the same language. He understands, and actually, those are often the most fun projects.

The motorcycle industry is filled with people who are passionate and love being here, in some contrast to what I’ve seen in the car world. Motorcycles are a great leveler and the egos are certainly not so pronounced. I get to work with excellent teams who get along and work together very well to achieve a common goal. In that sense, there’s free rein since we all enjoy working together. Of course, we still need to keep to the design brief and deliver on time, but that’s part of the job. You didn’t ask me, but that’s probably one of the most enjoyable things about the job is the passion of the team, the working with people who are equally passionate about motorcycles as I am, solving problems and being creative with like-minded souls is very rewarding.

Is it difficult to switch from designing one kind of motorcycle to another? Do they require different processes?

NG: Every brand has got its own surfacing language or design language. I guess because I’m sort of working under instruction from the designer…there’s never been an issue. I can adjust. I do know what the brand languages are. They would say, “This needs to be flat. Flatten this out.” It’s not a problem I’ve had to contend with to kind of adjust between different design languages.

Because they give you the guidelines anyway?

NG: Yeah, and because I know motorcycles, I know with certain brands, what their design language is, how they do their surface treatment. You’ll see in the sketch whether it’s super angular, like Kawasaki for instance, or if it’s more sculptural like MV Agusta. What’s common across all projects, across all brands is to translate the key elements of that sketch into the model. There are normally a couple of key lines or elements that make up the whole gesture of the bike. Then you really focus on those elements. It’s part of the job to figure out what the essence of that sketch is that needs to be translated into 3D. When you understand that, it manifests itself in surface proportions and transitions that work to support the main theme. If you just take their sketch and model something in without understanding what ties the whole design together, then the whole design won’t look like the sketch. It sounds a bit arty-farty, but that’s it basically.

What is a beautiful design to you?

NG: Traditionally in motorcycles, it’s not quite the same as cars where you’ve got lines, you’ve got more proportion and stance and stuff. I’ve had an epiphany over the last few years about just simplify, simplify, simplify. Coming back to my point about saying I have to try to talk tactfully to designers – I’m often trying to push them for simplification. The bikes that look good a lot of the time are those bikes where everything supports a unifying theme, form language, or direction. To me, beautiful designs eliminate anything that isn’t needed. Simplicity is timeless. However, I sometimes fear, especially with electrification, that we might be heading toward an “appliance” aesthetic. That would be simplification gone wrong. Motorcycles – electric or not – are still machines that have a soul.

What I find the Italians, Ducati especially, do really, really well is relatively simple surfacing coupled with such beautiful attention to detail of all the components. There’s nothing that’s an afterthought. Every single component just has that nice proportion and is interlocked with the surrounding components just in a beautiful way. Each component could be hung on the wall as a piece of art. Nothing is there that doesn’t need to be there. It’s just literally like, there’s a beautiful looking heat shield, but it’s no bigger than it needs to be. It’s carbon, and we’ve pushed it as close to the exhaust as we can. In the case of the Italians, we probably pushed it closer than we should, and we’ll have to recall it. But that’s fine. To come back to the thing about beautiful, it’s really just as simple and light as possible. It says everything it needs to say in as few words as possible.

There are other contemporary motorcycles coming out that are pretty cool, like the Husqvarna Vitpilen and stuff. They’re cool and simple. For me, that is almost as close to a simple, producty aesthetic as I would like to see things going.

When do you know you’re done?

NG: When the time plan says we’re done. That’s it. It’s not about me. The designer will keep on changing. The designer will keep on wanting to refine it. Nothing is ever perfect. If you spend all day looking at something, you’re always going to see, we could just line those things up a little bit better. Basically, it does come down to this is the day we need to stop working because there’s a budget for this project, and you’re not going to keep paying me if I go over that date. So, it needs to be finished. That’s when you know it’s done.

If you were like [Massimo] Tamburini doing the F4, you have years and years and there was seemingly no time limit. I heard CRC took 10 years to perfect his vision for the F4, and in the end, it was a beautiful motorcycle. If you’ve got deep enough pockets to pay for that development, then you have the opportunity to make things really, really perfect. Obviously, being a design genius helps. That’s it.

That’s unfortunate. I was hoping there would be some sort of definitive point other than an enforced deadline.

NG: When you look at it, and you can hear the angels singing. That’s also a good sign [laughs]. It’s like anything in the corporate world. There’s a deadline. As much passion as we’ve got for this thing, there are bean counters behind it, and they’ve assigned a certain amount of time and money for this thing. There are engineers that are cued up to do their job, so they need the data. So, the start of production is a fixed date, and they work back from that start production. All the testing and stuff, it may vary by a week or two weeks – in some cases a month or so – but it all depends on the manufacturer. The bigger manufacturers have got really strict processes. They’re really like, this is the deadline. Get it done.

Where do you see motorcycle design going in the future?

NG: The thing is, what we love about motorcycles is it’s a machine, and us riding the machine. We have an emotional attachment to them. The thing about the majority of cars is people don’t really like driving their cars. I don’t really like driving a car if I don’t have to because I hate sitting in traffic, and that’s what you do if you drive a car. It’s a necessary evil. That’s not why we ride motorcycles. It’s not a necessary evil; it’s fun and efficient transport.

Sorry to get slightly dystopian here, but I’m worried that in the future, with a transition to autonomous electric cars, this could spell the end of motorcycles. Human-operated motorcycles will probably not mix well with a network of connected, autonomous cars. And even if they endure, it will be a completely different consumer who rides those motorcycles, our kids, and with no nostalgia for the roar of a gas bike or it’s aesthetics. They may well appreciate something more producty, as transport, in general, gets viewed as an “automated service” rather than being a thing you own. Surely though, whatever happens on the roads, motorcycles will endure as recreational vehicles on off-road circuits, so perhaps with quieter electric race bikes like the Lightfighter (another cool project Nick is involved in), more circuits will pop up all around to make this possible. This would certainly take the sting out of losing access to the roads.

But to come back to your question about the future of motorcycle design, I can well imagine a Daniel Simon-esqe future aesthetic being more widely adopted. Man, I love that Daniel Simon aesthetic. Clean, muscular surfaces with a smattering of nice technical details. The move to electric vehicles is bringing with it acceptance of a new “futuristic” look, which I, for one, enjoy. Just as long as it doesn’t get too producty. Like I said before, we have to adapt to changing times, but hopefully, I can help steer the ship in the right direction.

If you want to see more of Graveley’s work, be sure to follow him on Instagram ( @claymoto_design) or visit his website, claymoto.com.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

This was a good read, along with part 1. Nick Graveley is one of the lucky ones who's work is something he loves and he's actually good at it. Also he's a total pragmatist about his job and what can and can't be done within the constraints of finalizing his work so the product can move forward.

I appreciate the candor in his response to "When do you know you’re done?"

But his use of producty as though I should know what that means is annoying - because I don't.

This I can relate to. Working on a great team, as he describes, really is rewarding.

Not as rewarding as reading all the MOronic content around here, of course.

There's only one MO.