Skidmarks - The Mouse and the Diavel

Neither the mouse nor the boy was the least bit surprised that each could understand the other. Two creatures who shared a love for motorcycles naturally spoke the same language.

—Beverly Cleary, The Mouse and the Motorcycle, 1965

If you ever ask me how to write a story, I’ll paraphrase the advice about how to sculpt a convincing statue of a horse – you just chip away everything that doesn’t look like a horse, revealing the beautiful artwork that is hidden in every block of marble. When I write a sentence, I have to see the sentence I write – I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to dictate – because a well-written sentence just looks right to me, somehow.

Spy Shots: Ducati Diavel Gets A Makeover!

I’m guessing my sense was honed by many, many years of reading before I began writing professionally. Even my low self-esteem can’t deny the fact that I’m a good enough writer that people actually pay me to write stuff for them. Some of this talent may be genetic – both of my parents could write – but I think I know how words should look on a page (either print or web) because I read so much as a child.

The irony is that I read so many books I can’t remember most of them. I know I read a huge amount of sci-fi in junior high and high school, along with plenty of history, but I also read a lot of run-of-the-mill juvenile fiction. You may have also – Judy Blume, Roald Dahl, Madeline L’Engle and others, but Beverly Cleary’s understanding of kids’ minds made her easy to read and memorable.

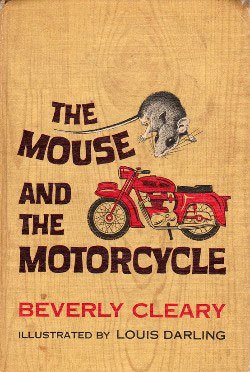

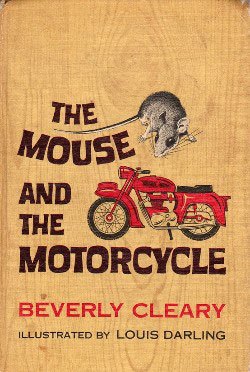

Fast forward to me at 46, with a three-year-old going on four. My wife (a children’s librarian, like Cleary) brought home a book I remember reading, maybe in second or third grade. I wasn’t really into motorcycles as a kid, but The Mouse and the Motorcycle was endlessly fascinating to me. So when my wife brought home a copy, richly re-illustrated in 2014 by Jacqueline Rogers, I was excited to re-read it.

In the book, a small boy named Keith is staying at an old, rundown hotel in the Sierra Nevada foothills during a family vacation. A young mouse named Ralph is watching him play with his toy motorcycle, and decides he wants to ride it. No, not “wants” – he needs to ride it. Magically, just by making a moto-sound with his mouth, (“pb-pb-b-b-b,” is how Cleary writes it), the motorcycle starts up, speeding the ecstatic mouse into all sorts of adventures. “To the mouse the sound spoke of highways and speed, of distance and danger, and whiskers blown back by the wind.” F-k yeah!

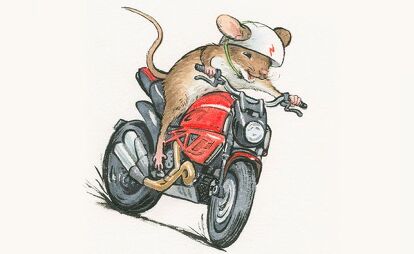

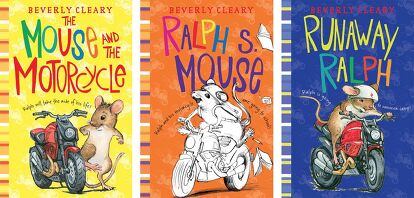

The book is a fun, breezy read, great to read to your kids or to let them read themselves (recommended ages 8-12). But what grabbed my attention was the cover illustration, showing a cute little mouse kicking the tire of what looks like a Ducati Diavel. I remember a ’60s-styled bike on the copy I read in grade school. What happened? Did Beverly Cleary hang out at Starbucks and develop an obsession for Ducati?

The book brought up plenty of questions, but interviewing Cleary was out of the question – she’s 99 years old – still “sharp as a tack,” according to Rogers, but quite private. However, Rogers was cheerfully available to answer my stupid questions about her work.

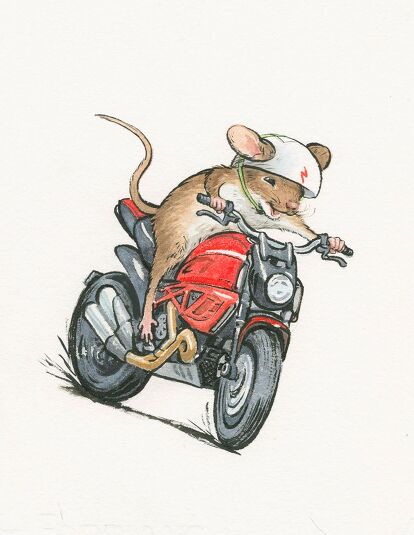

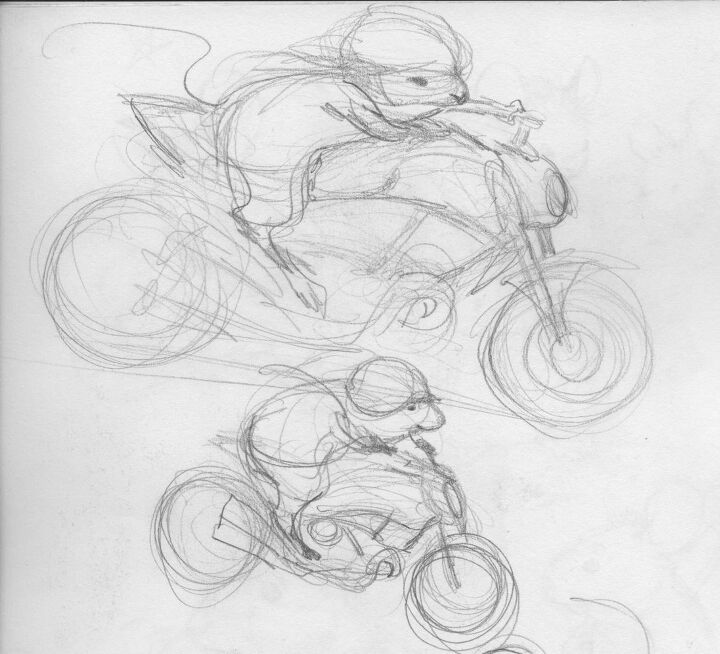

First off, let’s get this out of the way – why a Diavel? Well, Rogers told me in a phone interview, she wanted an updated look, as Harper-Collins hired her to breathe new life into the 50-year-old mouse tale as well as other Cleary books. For the 2014 edition, she decided the motorcycle should be new, as “my style of art is classic, it’s not a trendy, modern style, so I better at least have a modern motorcycle, or it will look really dated.”

Roger’s process surprised me – instead of just working off of photos or an actual motorcycle, she used a small toy as a model. “I had to be able to turn it around, to hold it in my hand and be able to draw it in every position.” She went to Wal-Mart and found a set of three small toy motorcycles. One was a dirtbike kind of thing, which wouldn’t work because a mouse’s legs would be too short to reach the controls, and the other was too old-fashioned looking. The Diavel, with its sleek and futuristic styling, was the only one that “could have worked.” Her toy Diavel (which she treasures, she says) was too dark, so she gave it red bodywork, unwittingly making her a true Ducatisti, if you ask me.

What was a mystery to me is Cleary’s knowledge and love of motorcycles. I haven’t been able to find an interview about her regarding Mouse, but it’s clear she gets it, impressive for any non-rider, much less a middle-aged librarian (she was 49 when she wrote it). I thought maybe her husband of 64 years maybe had a motorcycle, but there’s no mention of that anywhere.

Luckily, Cleary has written several memoirs about her life, and that’s where I found my answer. Cleary grew up in Oregon but moved in with family in Ontario, California after high school to attend community college. One of her cousins, the 15-year-old Atlee, had an adventure when another cousin rustled up a motorcycle for him as described in her book On My Own Two Feet:

“He found a broken-down motorcycle for Atlee to tinker with. Atlee worked hard on his motorcycle, and one day, with pops and bangs, got it to run. We all rushed outside to see the miracle: Atlee riding around and around the house on his red motorcycle. He lent me a pair of pants and took me for a wild ride – at least, it seemed wild down Euclid Avenue. Everyone who saw us cheered.”

If that doesn’t make you smile, nothing will. The same goes for The Mouse and the Motorcycle. Ralph the mouse just loves to ride. He loves the freedom, danger and adventure, as well as that essential “pb-pb-b-b-b” sound we just can’t live without. Cleary didn’t have to use a motorcycle – the story would have worked just as well if it had been a tiny British sportscar, or maybe one of those cool Alfa Romeos from the late ’50s. But she knew there’s something special about motorcycles you can’t match with any other kind of vehicle, and since the real secret of writing is telling the truth, she had to tell this story. Motorcycling is richer for it. Thanks, Ms. Cleary.

Huge thanks to Jacqueline Rogers and Harper-Collins.

Gabe Ets-Hokin is Chief Visualization Officer for Twundit, a tech start-up that will assertively recaptiualize virtual e-services and rapidiously embrace orthogonal quality vectors as well as provide dry-cleaning services for small rodents and amphibians.

More by Gabe Ets-Hokin

Comments

Join the conversation

I read the first book as a kid, my mom was adamant about us reading and always having a large selection at home to choose from. I've passed on my old hard-bound copy of the first book, to my niece when she was about 9-10, then she gave it to her daughter when she was 8. It's still in the family. Love seeing the new illustrations!

http://www.smdailyjournal.c...