Observations From the Road – Breaking It Down

The sun beat down and the road stretched out before me, an unbroken ribbon of blacktop wending its way into the distance. It was the kind of day that made me feel happy just to be alive, and even today the feeling remains so strong that it takes only a moment to recall every sensation. There is something magical about being on a motorcycle and everyone who rides knows the feeling.

Outside, exposed to the elements, you can connect to the world in a way that is otherwise impossible. The road fills your vision as it rushes towards you, and your ears are filled with the sound of engine noise and the tearing wind. Your skin prickles and reddens beneath the glare of the sun, its rays uncut by the luxury of tinted glass that even the simplest of cars offer these days, and every hair on your body feels the pull of the wind as it swirls around you. The scent of flowers and loamy earth make their way into your helmet where they fill your olfactory while the taste of dust and even the occasional bug helps draw you further into the moment.

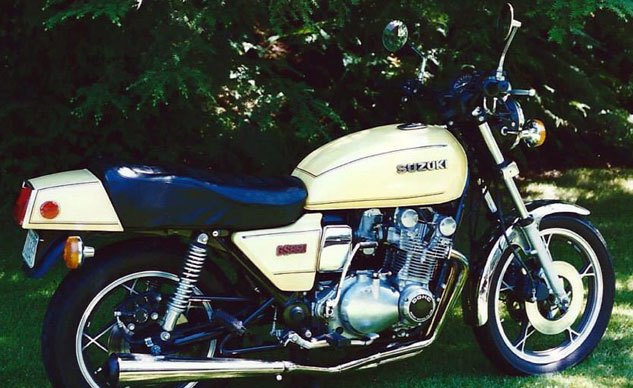

Beneath the sensory overload, your mind works smoothly, making the thousands of unconscious decisions per second that keep you firmly in control of the mechanical beast under your seat. Your right hand works the throttle of its own volition, while your body maintains the bike’s balance in a constant, intuitive dance against the push of the wind and the flaws of the road whizzing beneath you. Your conscious thoughts are directed towards the things that will keep you alive, predicting the ebb and flow of the traffic around you, spotting approaching road hazards that will require more than the simplest of responses and, perhaps most importantly, listening for emerging mechanical issues. And it was a mechanical issue that much of my own attention was focused upon.

After gassing up, I made my way across town and out onto the road that would lead me back up into the high hills and home. I knew this road well, had traversed it countless times on the back of my bicycle when I was in high school, and had driven it about a million times since. It was rural, but fast, and I always enjoyed airing the big bike out on its long straights. As I turned onto it, I slammed open the bike’s throttle and waited for the bike to begin its headlong rush. It never came. Instead, the back of the bike broke loose and stepped out to the side. I caught it reflexively and brought the bike back into line, but between my legs the big engine faltered. I closed and reopened the throttle but the bike merely shook in response. I knew at once it was bad and directed the stricken machine onto the narrow bit of hard shoulder the road offered.

As I rolled to a stop two things struck me, the sudden silence and a growing puddle of raw gasoline beneath the bike. A cursory examination told me the gas was coming from a rubber tube that led down from the top of the bike and emptied just in front of the back wheel. The back tire was wet and a long line of spilled gasoline stretched out behind the bike to the point on the road where the back end had broken loose. Clearly, I would be going no further.

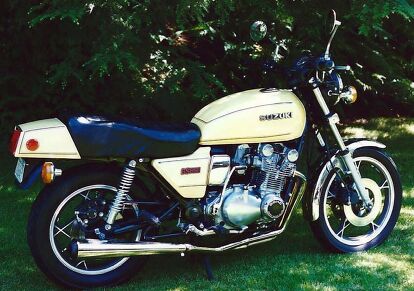

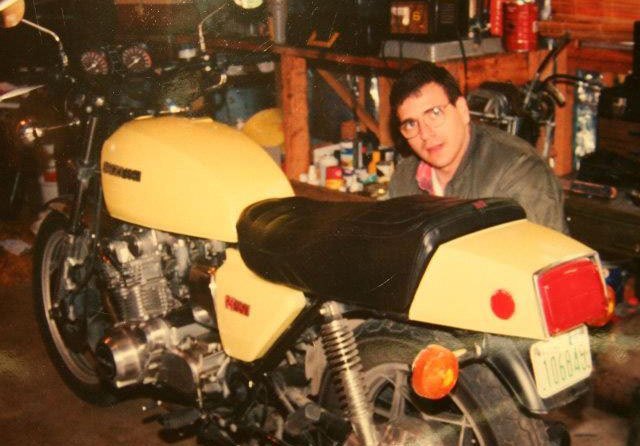

As quickly as I could, I found the petcock and switched it to the off position. The flow of gasoline stopped at once, and my earlier fears had come true, I knew. A bit of rust, a chip of paint or perhaps a spec of just plain old grit had been lingering in the bottom of the tank and, when I had switched to the reserve, it had worked its way down into the fuel lines. With no in-line filter to stop it, the piece had ended up in a needle valve, causing it to lodge open, and now fuel was free to flow down into the bowl of one of the bike’s four carbs where it overfilled the reservoir and came out through the overflow tube. A tube that just happened to empty right in front of the back tire.

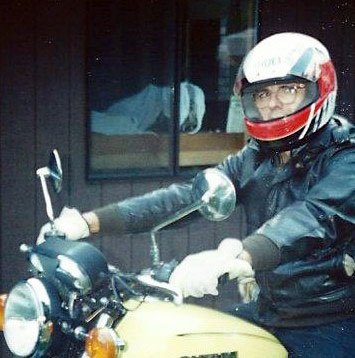

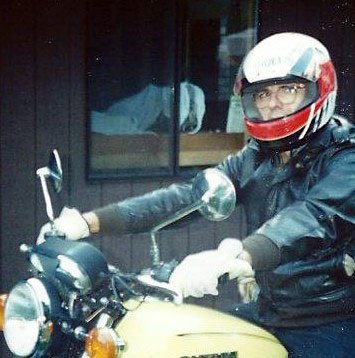

I took off my helmet and hung it from the rearview mirror and unzipped my leather jacket. Now that the bike was dead, the rush of physical sensations of the day were gone as well. Reality reasserted itself and I was suddenly struck by the sheer size of the world around me. In my mind I knew that I was only a few minutes’ drive from home, but now as I thought about the long straights I had so eagerly looked forward to blasting along, I realized just how far from home I really was. It would take hours to walk and although I dreaded the idea of leaving the bike for even a short time, it looked as though I was going to have to.

I was still pondering my walk when the steady thrum of an approaching V-Twin reached my ears. The sound was unmistakable, American Iron, and I dreaded the encounter. Many Harley guys were insufferable snobs, I knew, and I’d heard more than my fair share of stories about guys broken down by the side of the road being spit upon, or worse, as they went by. Still, as he hove into view, I stood tall and put up my hand to wave.

To my surprise, the big H-D full dresser swung off the road behind me and its rider killed the engine. He was, I thought, in every way a stereotypical Harley rider. Big, obviously blue-collar and sporting a bushy moustache. He wore a leather vest filled with worn, round patches, a pair of leather chaps and engineer boots. He didn’t bother to remove his half-helmet as he climbed from the bike, but he did, thoughtfully, remove his dark sunglasses before he spoke. “Any idea what the problem is?” He asked?

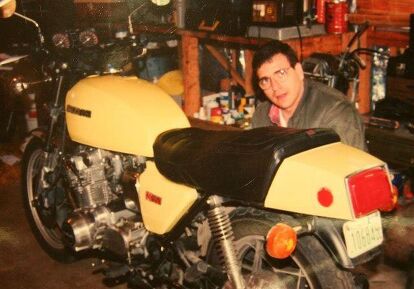

I pointed at the puddle of fuel beneath the bike. “I think I picked up a piece of crap in the fuel line.” I answered. ‘I’m not going any farther on my own.”

The big man nodded, “I just live up the road,” He offered, “I’ll go get my truck and take you home.”

I was shocked at the offer, but before I could protest, he went back to his bike and roared off in a cloud of dust. A few minutes later he was back and helping me load the stricken Suzuki secure in the bed of his Ford truck. Later, back at my house, he waved away my offer to reimburse him for his gasoline but accepted my hearty handshake. “I didn’t really think you were going to help me.” I confessed.

The big man laughed, “That whole Harley riders don’t wave and don’t help other people is bullshit. I’ve been broken down on the road enough times that I know when a guy needs help, you stop. It doesn’t matter what you ride – it feels the same when you are out there in the wind.”

I know today that he was right. As motorcyclists, we often draw distinctions based on the silliest of things. The brand of bike we ride, its country of origin or even whether it is a racer, a motard or a cruiser matters little in the grand scheme of things. When you are out there with the road rushing at you, feeling the sun and wind on your skin, the kind of bike you are riding is the last thing you are thinking about. In that instant, you are a creature of the moment, acting and reacting to the environment around you while reading the road and applying everything you know to the problems that arise. It is a solitary experience, and yet it is one we share with everyone else who rides. It’s a pity that we don’t always think of them all as brothers.

More by Thomas Kreutzer

Comments

Join the conversation

Great article. It is very true. I'm amazed at the number of people that buy into that stereotype. I pull over too, and have found it rewarding to help.

You know, there are good riders, and dicks, on every brand of bike. I've helped, and had help, from good souls on different brands, whether on my HD, or on my previous Hondas. I've also been passed by by less courteous riders. Riding is riding -- we are all brothers and sisters in the wind.