Church Of MO – Patrick Racing Road Star Warrior

Who doesn’t love a little raw horsepower on a Sunday? On this week’s Church of MO, we dial the clock back to 2002 and a special ride Brent Avis got to sample at Los Angeles County Raceway. The bike? A Yamaha Roadstar Warrior. Maybe not the first thing one might think of when imagining a drag racer, but with 150 hp and 150 ft-lbs blasting from that thumping V-Twin and through the rear wheel, the Warrior monikor seems appropriate this time around. How did Avis fare at this foray into drag racing? Read on to find out.

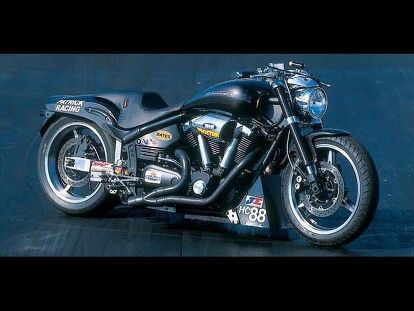

Patrick Racing Road Star Warrior

With all of our recent forays out to Los Angeles County Raceway, doing drag strip runs with various machines, I’ve come to a realization: Drag racing does not suck. In fact, it can be quite exciting. So when we got the invite to attend a little press function out at Pomona to ride a real, honest-to-goodness drag race bike, I was pretty anxious. With more than 150 horsepower and 150 foot-pounds of torque at the rear wheel, the day’s ride was sure to be anything but dull.

Showing up at the strip on an already sweltering hot morning, Patrick Racing had two of their Pro Star bikes ready to go, but not before those of us in attendance got the low-down on just what we were about to experience.

The Patrick Racing Warrior was designed to compete in the “AMA Hot Rod Cruiser Class” which has comparable rules to the Supersport or Superstock series. Driveline modifications, limited engine mods, and suspension work are allowed but the whole package of the bike plus rider must be greater than 800 lbs.

They’ve only been working on the Warrior since January of this year- a very limited time of R&D, indeed. But in that short time, they have accomplished much. Due to “an inherently strong engine design,” they’ve kept the stock clutch, transmission and crankshaft. In fact, the bike retains the stock starter and even with an increased compression ratio of 15:1, the Warrior has no problem roaring to life.

Internally, the bike uses Carillo connecting rods, custom-ground cams, custom designed 380-gram, 100mm pistons, and a crank that’s been lightened by six pounds (from 47!). Following class regulations, the engine retains the stock 4.4 inch (112mm) stroke. The cylinder heads use oversize valves, and have been worked over to the tune of about a 40% increase in airflow.

On the outside, the (moderately) stock airbox is still used, but it now connects to carburetors of unknown specification. These secrets were the most closely guarded; Nigel would only say that they were “heavily modified downdraft type carburetors.” Clear as mud, then. The team hopes to go back to fuel injection soon, but the carbs allowed them to progress quickly. The ignition system still uses a modified version of the stock computer, pushing the rev limiter a few hundred rpm higher.

The swingarm is lengthened, and rear suspension is now rigid, along with lowered front forks. Brakes are stock, with only one front disc retained. To comply with the weight limits, Patrick had to bolt an 80-pound chunk of steel on the front of the bike.

Speaking of progress- within three races, the bike set the league record, with a 9.86 ET @ 133 mph at Richmond, Virginia. Sixty-foot times are in the 1.44 to 1.45 second range, around 1/10 of a second quicker than the competition. For a large air-cooled twin, these are some impressive numbers, especially considering the time of development, the limitations of the class rules and how much of the bike is kept stock.

Before getting myself up to the start line for what would be my only run of the day, I spent considerable time asking Nigel and the bike’s officially talented rider Matt, about technique. After watching the other journalists botch launches and shifts and generally flail and wobble down the quarter mile, I was determined to be a shining pupil.

My main concern was the launch which, it seemed, most everybody was botching. The track was, according to all in attendance, the worst drag strip they’d ever run on. Even with a light coating of VHT on track and the bike’s professional pilot on board, the best run of the day was barely into the 10s. This, after the same bike had run a 9.86 ET just a few weekends prior. So, it was definitely the track, we opined, and so the theory going into my run was to be gentle with the bike. Just get off the line, roll the throttle open and make sure to hit the first-to-second shift, then focus on getting the power down.

The men who would be my Yodas that day expressed some concern as to whether the air-shifting mechanism was working properly and coached me on what to do if pressing the horn button (which was hooked up to trigger an upshift without having to roll out of the throttle) didn’t net me the desired result. I paid them, of course, no mind. Instead, all my focus was on being slow off the line, smooth on the throttle and precise when pressing the horn button.

Now, you might be saying to yourself that the thing makes only 150 horsepower, but 150 foot-pounds of torque is quite a bit. And that the Warrior is capable of sub-10 second times on a decent track is quite impressive. It’s something that’s not hard to wrap your mind around, but the way the thing feels is unexpected. Every twist of the throttle is greeted with a rapid climb in revs, followed by that most excellent blacka-blacka-pop-blacka-blacka orgasmic shuddering as the motor returns to idle where it just sounds like one-quarter of John Force’s funny car.

I idled up to the starting line but not before a brief burnout to clean off the rear tire and get the feel for the clutch. I also did a little practice launch to see how the clutch would feel. The result, with very little throttle, was still nothing but a spinning tire and little forward progress. This only confirmed my strategy to just get off the line, get rolling, and then start the run.

So up to the line I went, first tripping the pre-stage lights and then setting my feet on the pegs just like I’d been given the “secret tip” to do. Because the pegs are solid-mounted and close to the ground, I was able to put the heels of my boots on the pegs and set my toes on the ground to balance the bike. Done this way I wouldn’t have to pull any legs up and swing them back onto the pegs after the launch, unsettling the bike’s fragile balance. So, with toes dancing on the VHT beneath me, I crept forward and tripped the “Staged” light, waiting for the yellows to illuminate so I could begin the procedure I’d run through in my mind something like one thousand times in just the previous ten minutes.

When the lights flashed yellow, I started to creep forward. I think my reaction time was slightly quicker than half a minute, but that was my plan. To roll the throttle open slow and steady, building speed with no wheelspin, that was my plan and, shockingly, exactly the execution.

Up into the revs, I solidly hit the horn button to engage second gear, and thankfully the shift was as clean and precise as I could have imagined. Now it was time to get on with the whole throttle-twisting business. And then it came, with little more than quarter-throttle, the rear wheel started spinning. So I eased out of the throttle a bit to regain traction, then immediately I was back into the throttle, feeling for traction loss and then again, hooking it all back up before hitting the horn button. This finesse with the throttle was a constant for the entire run, as was tirespin that lasted well into fourth gear and a little bit of a weave as I crossed the line.

The result was an 11.2-something ET with a trap speed over 120 miles per hour. Not too shabby I thought, given some of the other runs of the day that approached the 20 second mark. But still, I was anxious to have a little debriefing with the Patrick Racing boys. You see, it felt like I did everything just about perfectly according to what they told me. Upon returning to the pits and shutting the beast down, I remained astride it. Though the ET may not reflect it, the Patrick Racing Warrior is the meanest, most violent thing I have ever ridden.

The bike did exactly what I told it to do. There was nothing unexpected other than the magnificent way the machine went about its business. And the fact that the Patrick Racing guys all said that, considering the condition of the track, my run was just about perfect. They said they could hear me nailing the correct shift points (a few hundred rpm south of the rev-limiter) and hear the bike’s motor revving as the rear wheel spun before hooking back up. Damn, I’m good. Can I go again? No.

My First Time–by Elliot the InternalDrag racing? I get visions of unsanctioned runs down stretches of asphalt at 2 am in the industrial desert of South Seattle. Guys with mustaches and Southern drawls wrangling machines with more horsepower than a locomotive down rubber-smeared tracks. Whatever the venue, the central tenet of drag racing centers on the most American ideals of instant gratification and vindication. Strategy? Must go fast in straight line, must beat guy in the other lane to the little line one-quarter of a mile away.

Personally I prefer the atmosphere of a good road race, so I was a little hesitant when Yamaha invited us out to play with the Patrick Racing Yamaha Warrior and other assorted Yamahas, at Pomona Raceway.

Many racing series claim to be production based but bear scant resemblance to their showroom ancestors. Not so the Patrick Racing Warrior. I was duly impressed by how much of the bike was in fact stock, and even more impressed with what the team had accomplished in only six months of R&D time. Team rider Mark Underwood calmly fired the surface-to-surface missile that is the racing Warrior downrange in 10.54 seconds–impressive enough to me anyway–and this on a hot day with very less than ideal track conditions.

While Minime had the divine pleasure of sampling the hardcore racer, sprogs such as myself were steered toward stock Warriors in grudge matches against each other (after the bigwig editors finished up their shootout on the bikes). There was a little wagering going on among the MO interns on who would win the all-important Minime/Hackfu showdown. (My wager on Mini paid off; Hackfu did well, but Minime made it further in the competition.)

It all, amazingly, wound up being an entertaining spectacle. There were some big egos running around, and it was cool to watch them get deflated by the Patrick Racing bike. Half the editors chugged down the track, often bouncing violently off the rev limiter, causing everyone to cringe in empathy for the bike’s internal organs. One guy (cough, Tim Carrithers, cough cough) struggled so badly to find the horn button (that activates the airshifter) that he pulled a 19.90 ET, but the other half of the participants managed to pull off respectable times. I was very proud to see MO well represented by Mini’s mid-11-second low-level flight.

Running down the track on even a stock Warrior turns out to be incredibly fun; I had resigned myself to the sad fact that I’d probably suck big time. I chose the darkest colored Warrior available (must intimidate competition), got some hints on the finer points of drag racing technique from my fellow staffers, then lined up for single combat against a representative of a rather large and influential print magazine. My heart was pounding hard by now and I wasn’t too sure about how I should go about this… I was nervous. Here I was, an undefiled drag racing virgin, about to take an experienced machine out for a spin. How would my performance stack up, would it all be over quickly?

Yes: The lights had already gone green before I could fully freak, and my combatant was heading towards victory– a moment of panic ensued. I pushed that big twin as hard as I could and it responded as gruntily as it could, carrying itself and my skinny butt downrange. At the end of the line, I couldn’t tell which one of us had crossed over first and I moseyed back to the pit area where I saw Calvin giving me a thumbs-up. Just being nice, I thought.

“Dude, you did well! You got a 13.10,” he told me.

What?! And I beat the other guy? Okay then, I’ll try it again.

It turns out that flying in a straight line as fast as possible on a motorcycle, any motorcycle, is a surprisingly pulse-raising experience. I made five passes on the track and got down around 12.93; on one pass, I beat a 2002 R1 (botched launch on his part). Hey, it counts.

I learned a lot from Brent and Calvin’s suggestions- they made a lot of difference in my times and it turns out that a power cruiser is a great bike to learn the basics on. Wheelspin was limited so launches were fairly straightforward, and unlike a lighter, more powerful sportbike with a short wheelbase, I didn’t have to be concerned about the added factor of keeping the front wheel on terra firma. These characteristics allowed me to concentrate on my weight transfer, reaction time, clutch/throttle modulation and shifting techniques. I learned to go by ‘feel’ of the bike and listen to the engine revs rather than focus on the tachometer, freeing up my eyes to concentrate on the Pro Tree lights; this alone resulted in a dramatic change in my reaction time.

By the end of the afternoon I was worn out from a combination of fast bikes, warm weather and lots of Yamaha-provided catered food. I had completed enough runs to get a taste of drag racing. And my fastest time of the day — a 12.93 on my fifth and final run — ain’t so far off the 12.5-second, 104 mph times from the magazine tests.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation