50 Years in the Grand Prix Paddock

After a half century in GPs, Giancarlo Cecchini keeps on wrenching

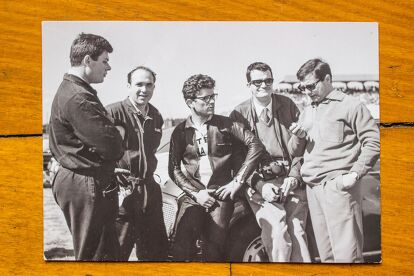

With 50 years in the world championships of motorcycle racing, Giancarlo Cecchini is almost surely the most experienced mechanic currently active in the MotoGP circus. He has eight world titles on his C.V. and has worked with legends like Saarinen, Pasolini, Provini and Carruthers. He remains in the paddock still today, helping out his son, Ongetta Rivacold, who helms a Moto3 team with rider Niccolò Antonelli. But his roots in Grand Prix racing stretch back decades.

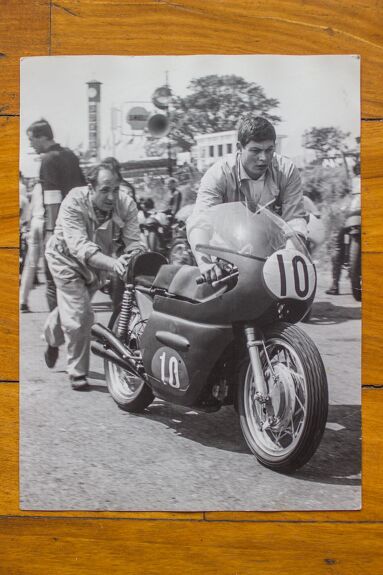

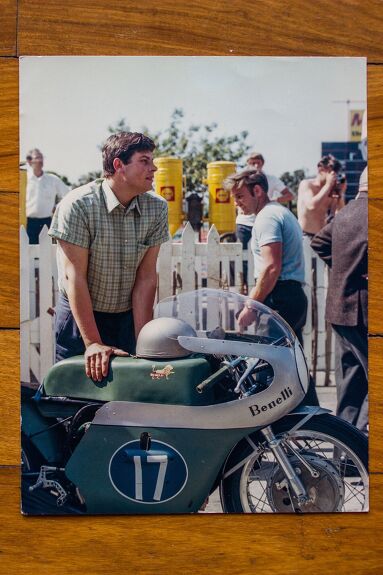

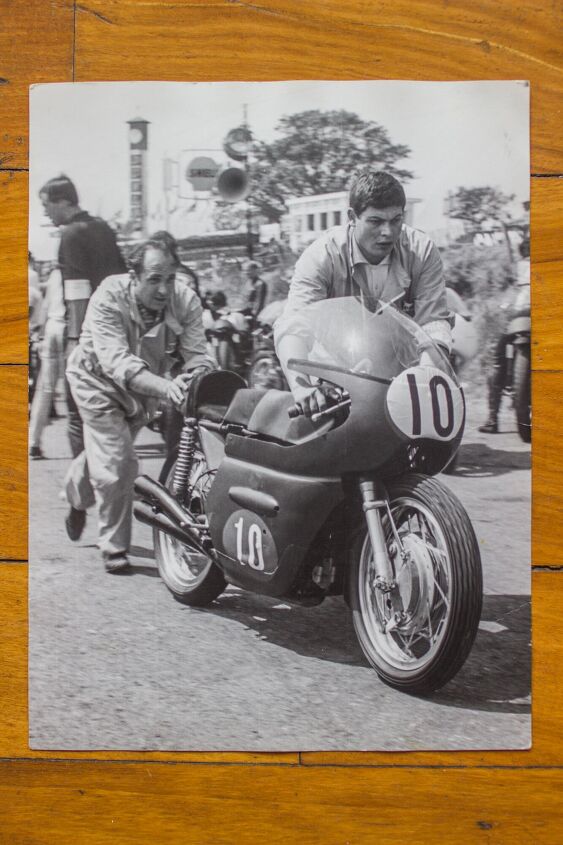

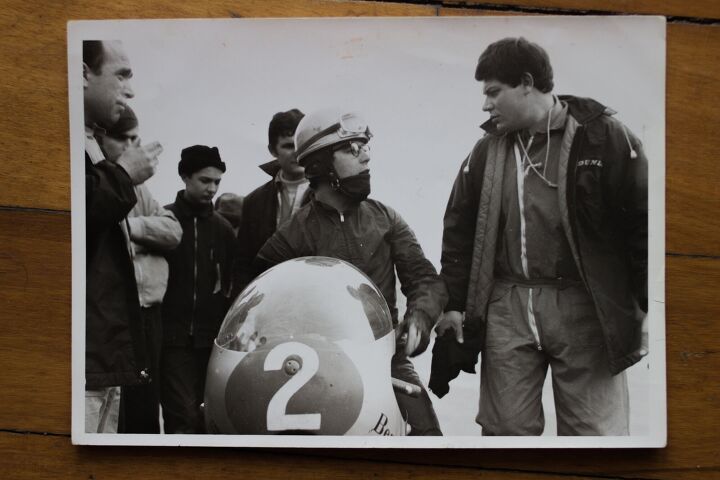

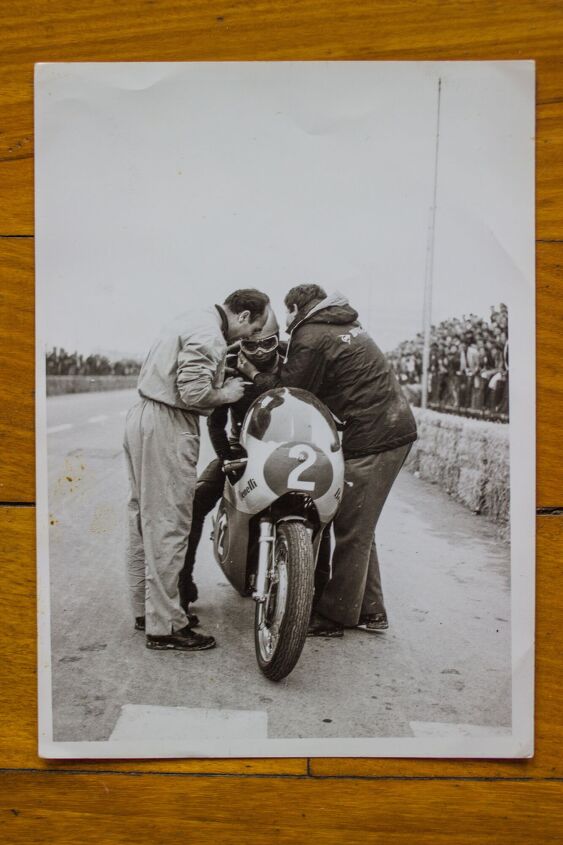

When citizens of Pesaro, Italy, were woken at four in the morning by a tremendous and repetitive roar in the 1960s, they knew it was Giancarlo Cecchini warming up the engine of the 250 prototype in front of the Benelli racing department. And they didn’t protest, because the company employed members of several local families, and was something the whole country was proud about. In the 1960s, Benelli’s racing achievements were considered with a mixture of patriotic, romantic and epic feelings.

“Crowds of people followed us,” Cecchini remembers, “on top of all when our rider Renzo Pasolini was fighting against Giacomo Agostini and the MV in the so called “Moto Temporada,” a series of road races that took place in the main cities of the Adriatic coast, like Rimini, Milano Marittima, Cervia and Riccione.” More than 100,000 spectators attended the events. “It was on the mouth of everybody, even grandmas chatted about Ago against Paso.”

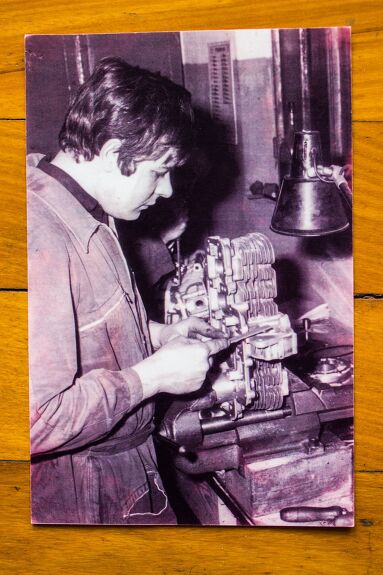

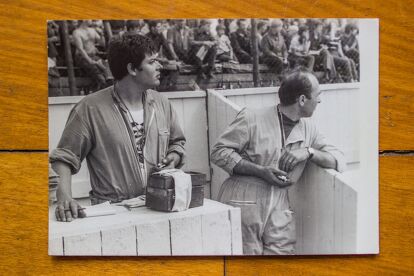

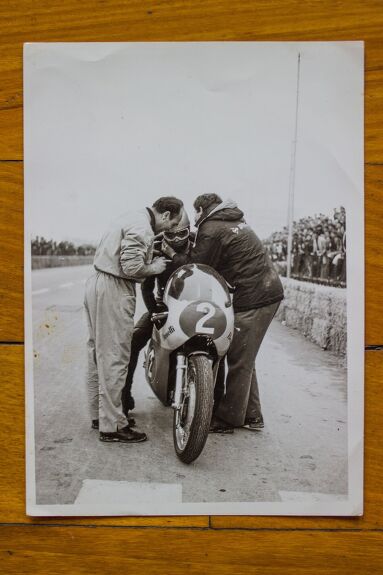

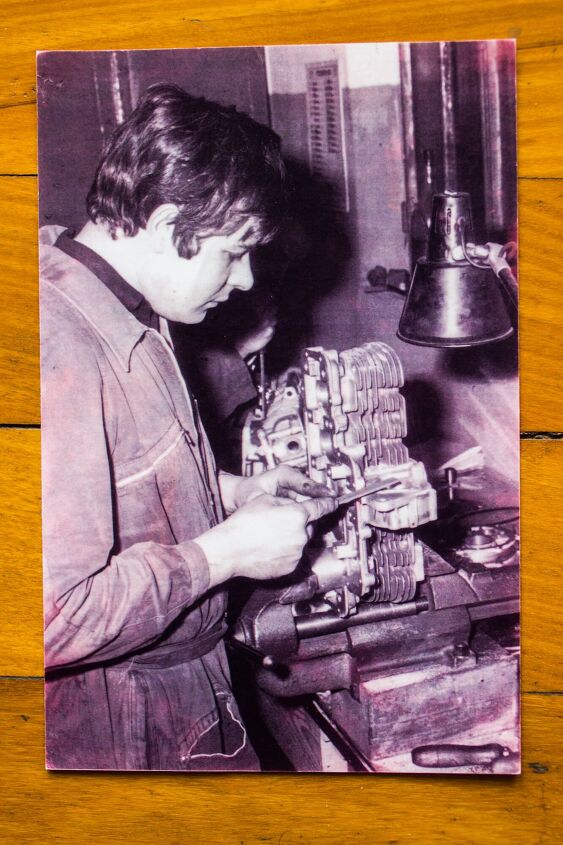

At that time, the activity of the Benelli team was hectic: “In the mid-`60s it happened that we went to Monza for the Friday and Saturday practices, then we packed up everything, returned to Pesaro, checked the engines in the racing department and reached Monza in time for the start of the Sunday race. Barely sleeping. In that era every part of the motorcycles was literally handmade, and a lot of skills were needed to create a competitive prototype. Today is different, it is often the computer that tells you what to do. Back then you had to test every single change and understand if it was an improvement or not. The job was very demanding.”

But nobody complained – being part of the Benelli racing department was considered better than working as a sound engineer or a roadie for the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Giancarlo had that clear in his mind since he was a young man, and he eventually snared a job at Motobi, where he met his first mentor, Primo Zanzani, who was considered the “wizard” of the four-stroke 250cc single-cylinder engine that showed its competitiveness in races all around Italy.

“I was 16 years-old and was working in a company that created gears for Motobi. Our workshop was very close to their factory, so I used to deliver the parts with a push cart. One day I simply met the boss and asked him if they were interested in hiring me, because I was fascinated by the people who worked in the racing environment. He said yes, and that’s how it all began. It was 1956.”

Motobi had been established in 1949 because of a series of disagreements within the Benelli family, from which one of the owners had decided to split in order to create his own business. In 1962, the company was absorbed by Benelli, and Cecchini ended up working in the racing department, preparing the 250, 350 and 500cc inline four-cylinder bikes.

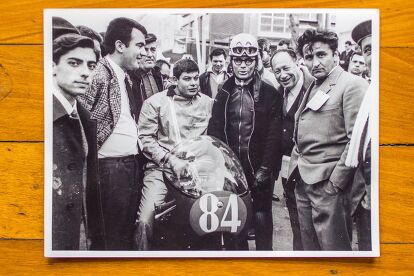

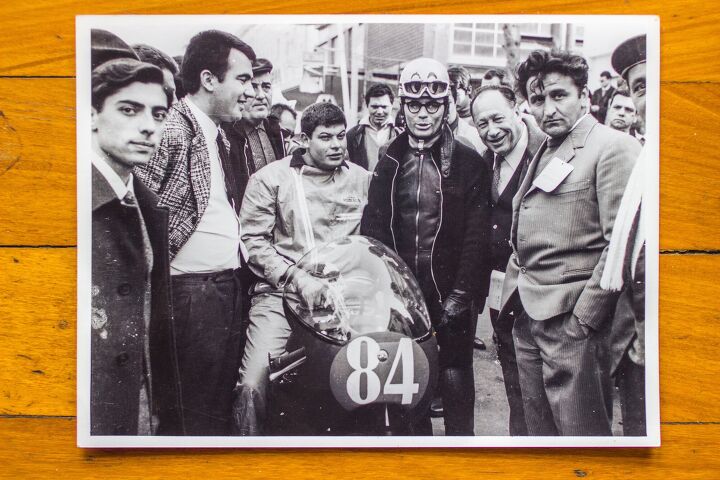

He worked side-by-side with rider Tarquinio Provini, which he remembers “as a very meticulous rider, sometimes maybe too picky… he asked us to make tons of adjustments and was never satisfied.” After Provini’s crash at the Isle of Man in 1966, which forced him to retire, Benelli hired Renzo Pasolini, with which Cecchini developed a tight and friendly relationship.

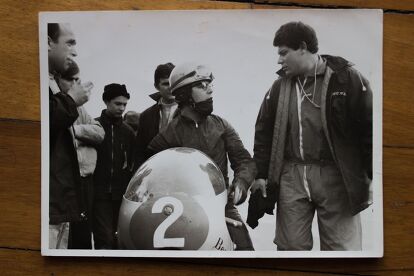

“He was like a brother to me,” the mechanic says. “He was very sincere and spontaneous. His riding style was really instinctive, I remember that when we raced in Assen, his only request was to change the position of the engine in the chassis to make it higher, because it touched the ground in almost every bend.” Cecchini also remembers Renzo as a fair person, who never complained about the team. “If there was an oil stain on his boot, for example, he simply hid it from the journalists. Nowadays, it seems that some riders can’t wait to have an excuse to justify their bad results, and show that the motorcycle doesn’t work well. It’s another world, but now it is well organized, if compared to the old Continental Circus, which was made of improvisation.”

Cecchini gives an example: “One year we leave Pesaro and head to the Isle of Man for the Tourist Trophy, without stopping for a nap or anything. Due to the fog while we are in the UK, we get lost. And we have no clue about where the car that was following us, with the owner and another member of the staff, is. They have the Pounds and the map, we have nothing. We stop at a gas station and refill the van. Not having any valid money, we show our Italian Lire. But the man at the gas station gets angry and tries to reach for his gun. We run away, but later I fall asleep and crash against a pole, where I injure my foot. I still feel pain sometimes.”

Pasolini was fast, but also unlucky and impetuous. He often crashed, and in 1969, after he injured his shoulder in Hockenheim, the team temporarily replaced him with Australian rider Kel Carruthers, who ended up winning the 250 championship.

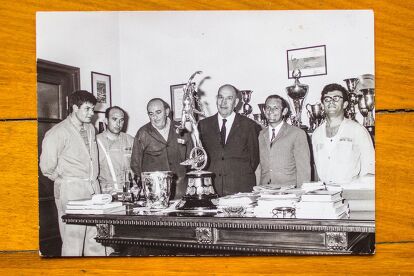

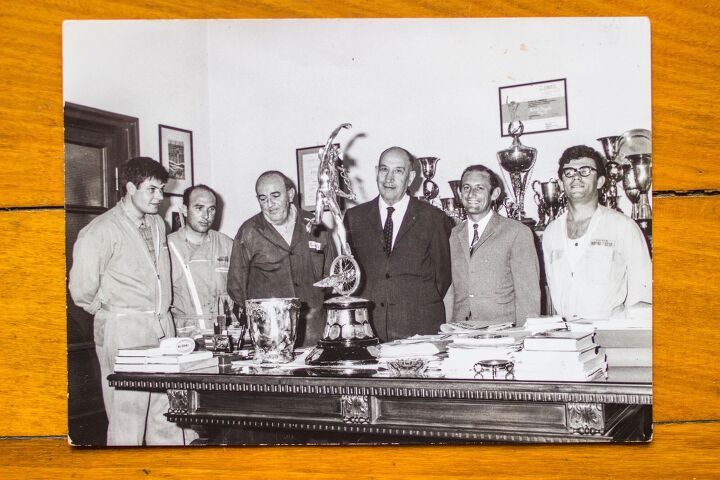

“That success was a big thing for us, but I particularly remember the feeling of winning the Tourist Trophy. Being first at the Isle of Man was maybe more special than winning the championship. When we came home, with the trophy in our hands, the Benelli owners treated us like heroes. And so did Pesaro’s citizens.”

Cecchini also had strong feelings at the end of 1972, when Finnish rider Jarno Saarinen, who that year had won the 250 championship with a private Yamaha, agreed to a one race-deal with a factory Benelli.

“We tested in Modena only once, and Jarno just asked me to adjust the handlebars,” Cecchini remembers. In Villa Fastiggi, a road race in Pesaro, Saarinen defeated Giacomo Agostini and his MV in both the 350 and 500 classes. “He was very kind and polite, very focused on what he was doing, a real pro,” the mechanic says.

One year later Cecchini faced a big change. He switched from Benelli to Morbidelli, leaving a big team that developed four-stroke engines to join a small and ‘family-style’ group led by the owner of a woodworking machinery factory, for which motorcycle racing was no more than a hobby. The Morbidelli team built and developed two-stroke engines under the direction of German engineer, Jorg Moeller, and won two world championships in the 125 class in 1975 and 1976 with Italian riders Paolo Pileri and Pier Paolo Bianchi.

Film Review: Morbidelli – A Story Of Men And Fast Motorcycles

“Moeller, after the second title, decided to leave us and join Minarelli,” the mechanic says. “The word in the paddock was that without him we were not even able to start the engines. Well, in 1977 we won two world titles, in the 125 and 250 classes, with Bianchi and Mario Lega.”

At the end of the year, Cecchini left the team and accepted an offer from MBA (Morbidelli-Benelli-Armi). He worked there for three years and helped win another two titles in the 125 class. Then he took on a new adventure with Sanvenero, a project led by another Italian businessman who loves motorcycle racing, but doesn’t get close to Morbidelli’s results. The following job is at Cagiva, before Cecchini’s decision to establish his own team, participating in the minor classes of the world championship.

The next title arrives in 2004, when a young Andrea Dovizioso, currently a factory rider in MotoGP for Ducati, puts himself in good light on a Cecchini-tuned Honda before moving to higher categories. The creation of the four-stroke Moto3 class to replace the two-stroke 125 class sees Cecchini working with his son in partnership with Honda and brings him back to four-stroke engines. But with a lot of changes.

He now works on 250cc Singles capable of more than 50 hp, featured with electronics and placed in aluminum twin-spar frames, something that in the mid-60s was not even imaginable. And now, due to exhaust restrictions, would not disturb the sleep of anybody, not even at four in the morning.

More by Jeffrey Zani

Comments

Join the conversation

Good stuff, MO. Racing season is here again!

Wow. What a life. What's striking in the photos is his youth among elders. He must be a very special and talented man. Those Old World guys didn't tolerate fools. The best stories are always about the people not the things.