The Wings Tour 2014: Leg One

This original Motorcycle.com editorial content was sponsored by American Honda.

What is the connection between motorcycles and airplanes? Growing up with a father who was fascinated by both, my youth was spent scouring the countryside for dusty barn finds, spinning a greasy wrench and flying, in the air and on the ground, wind in my face. It seemed that most of my dad’s friends were pilots and motorcycle riders too. Apparently lots of famous aviators are motorcyclists and vice versa. Charles Lindbergh rode an Excelsior Super X. Steve McQueen collected and flew airplanes (his favorite was a Boeing Stearman), along with his better known motorcycle obsession. Former racers Mat Mladin and Bob “Hurricane” Hannah are flying buddies. It’s no coincidence that the world’s top selling motorcycle company, Honda, uses a wing as its logo. Wings are also featured on the emblem of Moto Guzzi, a company formed by two Italian World War I fighter pilots. The Italians call a person mounted on a motorcycle the “pilota,” a pilot, who is a skilled operator in complete control of his craft. A rider is the guy who takes the bus.

So what’s the appeal that links two wheels and wings? Maybe it’s the three-dimensional freedom of motion that both allow? The ability to bank, turn and defy gravity? The romance of that perfect cocktail of speed, danger and adventure? This needed to be investigated further.

And so was born “The Wings Tour 2014.” The plan was to ride down the East Coast hitting as many aviation sites as we could manage, experiencing the best that two wheels and wings had to offer. Contemplating the motorcycle to take there was only one choice. What better ride to take a trip through aviation history than Honda’s Gold Wing? From its high-tech design to its complicated cockpit to its horizontally opposed engine, a Gold Wing just might be as close as you can come to flying while keeping the tires solidly connected to the tarmac. So I grabbed my granddad’s Air Force issue Flight Goggle 58 sunglasses and off we went.

Day 1

Our journey began in the nation’s capital. From the home of Air Force One at Andrews Air Force Base to the former site of the Martin factory just outside of Baltimore to the world’s oldest airport in continuous operation in College Park, Maryland the Washington D.C. area is steeped in aviation history. It is also home to one of the greatest aircraft museums and the largest collection of historic aviation in the world, the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum.

Just outside the D.C. city limits we picked up a 2014 Honda Gold Wing in Wings Tour appropriate stealth black (my designation, not Honda’s) at Honda Powersports of Rockville. As a kid my pilot father’s day job was as the sales manager of the local Honda dealership. Somehow a Gold Wing seemed to follow him home every weekend. My formative riding experiences were on the big machines. He didn’t plunk me down on that plush back seat. He stuck me on the tank in front of him, my five-year-old feet resting on the engine guards of those big flat cylinders, my hands reaching forward to grasp the bars. I wasn’t a passenger. I was a pilot.

No map. No directions. I was feeling all Easy Rider until I punched the Smithsonian’s coordinates into the Honda’s GPS. Along with myself and my co-pilot, we were taking along a navigator. The digital display took us through D.C.’s maze of angularly bisecting streets and traffic circles, dodging mini-vans with diplomatic plates and Segway tourists. We blistered in the sun at the stoplights, as the July afternoon heat index climbed to 100. The museum’s boxy shape was a welcome sight as we approached the National Mall, not only as the first stop on the Wings Tour, but also for its air conditioning inside.

The Air and Space Museum was the perfect start to our aviation adventure. Its exhibits trace the trajectory of manned flight, from drawings of flying machines by Leonardo Da Vinci to the technology of the Mars Rover. In between are priceless pieces of aviation history – Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, the Wright Flyer, Yeager’s Bell X-1.

A few feet inside the door, we saw our first motorcycle. Its frame held an all-American V engine. Not a Twin but a V-8. Glenn Curtiss got his start building motorcycles. When pioneering aviators came to him seeking his light and powerful engines he started building powerplants for airplanes.

The motorcycle in the Air and Space collection was Curtiss’ test bed for his new V-8. In a 1907 test he set an unofficial speed record of 136 miles per hour on tires so narrow they’d make a Tour de France rider wince. The motorcycle record stood for two-and-a-half decades (it was the fastest that any machine traveled until a car broke the record in 1911). Curtiss went on to rack up a long list of aviation firsts, becoming the bedeviling competition of the Wright brothers, and in the process, earned himself a place in both the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame. Part of the company he founded still lives on today in the Curtiss-Wright Corporation.

Since the earliest days of the internal combustion engine motorcycles and airplanes have been inextricably linked. When the Wright Brothers made the world’s first airplane flight in 1903, two men with the last names Harley and Davidson decided that bicycles needed to have an engine between their two wheels (Orville and Wilbur had started out building bicycles too). Both motorcycles and airplanes seemed to appeal to the same kind of person – part adventurer, part daredevil, with plenty of mechanical aptitude thrown in for when the machines, invariably, broke down. Both operators wore the same uniform – boots, leather jacket, silk scarf, goggles and leather helmet. Both were often killed or maimed for their passion.

By World War I, both airplanes and motorcycles were just hitting their stride. It was as common to see an Indian, a NSU or a Triumph at an airbase as it was a Sopwith, a Fokker or a SPAD. The Golden Age of Flight that occurred between the wars produced such beautiful and iconic aircraft as the Gee Bee racer and the Lockheed Vega. At the same time motorcycles were in their own golden age, with designs like the Indian Four, the Brough Superior SS100 and the BMW R32 (a manufacturer of aircraft engines, BMW was forced to diversify after the prohibitions of the Versailles Treaty).

While the museum’s collection overwhelmed us inside, outside the July heat boiled over into a thunderstorm. Wind and hail. Pounding rain. We pushed out like a pair of air mail pilots braving the elements in an open-cockpit biplane. The weather snarled the notoriously horrible D.C. traffic. Standing water and bumper-to-bumper cars. In the miserable conditions the Gold Wing’s ABS brakes hauled us down like the tail hook on an aircraft carrier.

The delays kept piling up in the July 4 Eve traffic so we called it a day, making an emergency landing at our hotel just short of our final D.C. destination.

Day 2

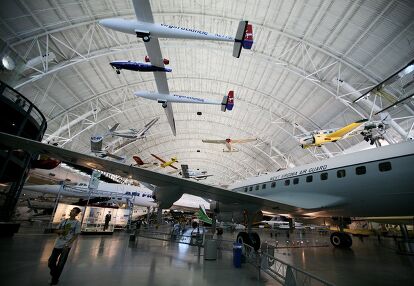

Our thwarted stop from the first day had been the Steve F. Udvar-Hazy Center. A sister to the downtown D.C. Air and Space, the Udvar-Hazy is where they keep the big stuff. Unhampered by the confines of the National Mall, the museum sprawls on the outskirts of Dulles International Airport. Accessing the Udvar-Hazy is the antithesis of the downtown Air and Space. Located a few miles from the interstate with an ample parking lot and lockers inside big enough to stow all your gear, it’s a perfect motorcycle stop.

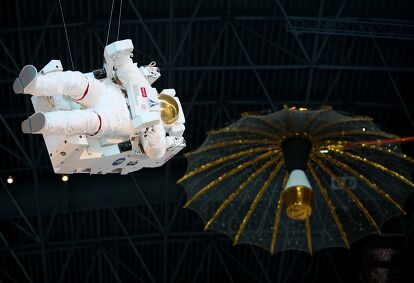

Inside, the Udvar-Hazy has its own share of famous aircraft, from the Concorde to an SR-71 Blackbird and the Space Shuttle Discovery, along with the only surviving examples of numerous rare planes. Displays highlight aircraft technology including a gallery of engines, their pistons, camshafts and valves looking very familiar to a gearhead.

Soaking in this timeline of aircraft development I couldn’t help but think of our motorcycle outside. Introduced in 1975 as the ultimate in two wheels, over the years the Wing had adapted and changed in response to stiff competition in its heavy touring market niche, the motorcycling equivalent of long range strategic bombers. While the others had come and gone, the Wing is still going strong at nearly four decades. The B-52 of the motorcycle world, the GL1800 is the fifth itineration of the series.

From the top of the museum’s 164-foot observation tower, the mountains of Virginia beckoned. So far on the Wings Tour we’d spent more feet time than seat time. That was about to change. Fifty miles from Dulles airport lay the entrance to Shenandoah National Park. The park’s only major road, the Skyline Drive, follows the ridgeline of the Blue Ridge Mountains for 105 miles of two-lane blacktop bliss, offering alternating views of Virginia’s Piedmont and the Shenandoah Valley. With long days of straight, flat interstate ahead we couldn’t pass it up.

Some people celebrate freedom with fireworks and hotdogs, but I’ve always found the best way to spend the Fourth was on a motorcycle. There is no finer expression of Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. And there’s no better place to escape the July heat than on top of a mountain. The air temperature dropped 25 degrees as we made the 2,500 foot climb to the ridgeline.

Riding a motorcycle on Skyline Drive is the equivalent to flying a high-wing, tail dragger. “Low and slow” my dad used to call it. The 35 mile-per-hour speed limit is enforced more by traffic than park rangers. With the surrounding countryside lying a thousand feet below, the overlooks afford a bird’s eye view of a patchwork of farm fields, roads and meandering rivers, the same view you’d get buzzing overhead in a small plane. The Gold Wing handled as light and comfortable as a J-3 Cub at the parade pace, its six-cylinder Boxer purring like a Continental A50. The engine’s broad torque curve let us lug it down as we slowed and then add some gas to speed back up, ignoring the transmission.

Total Miles, Leg One: 331

Average Speed, Leg One: 37 mph

Total Trip Miles to Date: 331

Average Fuel Consumption (mix of urban and interstate riding): 30 mpg

Average Fuel Consumption (mix of Skyline Drive and interstate riding): 38 mpg

By the time we reached the southern portion of Skyline Drive, the metro tourist traffic disappeared and we often had the road all to ourselves. I cracked the throttle open and pushed the Gold Wing’s pace, diving later into the curves and getting the most out of our ground clearance. The Wing’s solid handling continued as the tempo increased, its linked brakes trailing-off the extra speed from turns entered too hot.

As the sun sets prematurely on a summer holiday, so the ride along Skyline Drive ended too soon. At the end, a sign denotes the start of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Like a dog looking at a cat while its master yells for it to get back on the porch I looked south, then east, then south again. Focus. Focus. Before I knew it the Wing had turned itself east and we were off in search of more aviation adventures.

The ride continues in Wings Tour: Leg Two

This original Motorcycle.com editorial content was sponsored by American Honda.

More by Jeremiah Knupp

Comments

Join the conversation

might need to take the FZ up there

I've always thought the perfect day involved a motorcycle ride to the airport. Loved the article.