One Thousand Miles of Solitude

Given a long enough timeline, all equipment fails.

For my new waterproof touring boots that timeline lasted approximately ten minutes after the sleet and freezing rain began to fall. What started as a damp sensation where the leather uppers met the rubber sole soon developed into a full-blown soggy numbness. These boots were going back to the dealer.

But wet feet were the least of my worries. My faceshield and the wind screen on my Ducati 748 were starting to go opaque with the ice that was beginning to form on them. Hand and foot controls were developing a greasy uneasiness to them, as the Ducati skated along the interstate with a confidence-killing vagueness. Cars began to pull off the road. I began to consider the possibility that my Bike Week journey to prove the practicality of the superbike of the century might end prematurely, quite possibly painfully.

There's something about growing up in a farming community that instills a value system where an object's worth is equated with its ability to function. I could never justify having money tied up in a motorcycle that would be ridden ten weekends out of the year. For me to own a motorcycle, it had to be used as year-round daily transportation.

Then came the ad in the local paper.

2000 Ducati 748. 2,500 miles. $3000.

A notorious object of moto-lust, the Ducati 916 had debuted just as I was getting old enough to ride on the street and I joined a motorcycling generation in my fascination with the machines. Ducati superbikes are motorcycles that hold supermodel status, with a reputation for beauty and amazing

performance, but a price tag and high maintenance needs that keep them beyond most riders' realistic grasp. With the closest dealer located over an hour's drive away and a price that was several grand beyond a comparable Japanese sportbike, I settled with the fact that a wall poster was the nearest I would ever get to a Ducati superbike.

I read the ad twice before calling. The man who answered told me that he was the original owner and the bike had been crashed by a friend. He had let it set around his garage for two years, hoping someday to fix it, before deciding to sell. We set up a time that evening to take a look.

To my surprise, the accident damage was not that bad. The motorcycle had been panic braked and low-sided in a corner and was scuffed all over, but most of the damage appeared to be cosmetic, with straight forks, frame and rims.

I made an offer and drove away to spend a sleepless night. The next morning, I received a call informing me that I now owned a Ducati superbike. It was at that point that I realized that I had just bought a motorcycle that I'd never heard run. But by the time I arrived with a truck, the bike's previous owner had installed a new battery and the first thumb of the starter brought the Ducati to life with the mechanical rattle and throaty rumble that I instantly fell in love with.

The 748 was my first non-Honda and I planned to press it into daily commuter service. My plan was to ride it for a while, have fun, and if the Ducati proved to be an impractical daily ride, I would sell it at the end of the summer. Being possibly the first person to purchase a Ducati superbike to ride to work on, I had several practical concerns. The first was the cost of parts. Having been around for 10 years with very few design changes and often used as a race bike, my rebuild process found stock parts to be plentiful and affordable. Three months later, the bike was on the road and I was hopelessly addicted to Ebay.

The next concern was maintenance. With a 6,000 mile valve adjustment interval, at the rate I ride I would have to dig into the heads three times a year. A Ducatista who lived an hour away helped me through my initial valve adjustment. In the first great myth-busting experience of my Ducati ownership, adjusting desmodromic valves proved to be no more taxing than contemporary inline-four sportbikes.

Gas mileage as a daily driver was also an initial concern. I knew that a combination of performance gearing and huge throttle bodies on modern sportbikes could mean a thirsty 40 miles, or less, to the gallon. Sporty V-twins are notorious consumers, with a friend's

Super Hawk going dry at right around 100 miles on road trips. Again, the Ducati turned out to be a pleasant surprise. Thanks to its tall gearing, in my mix of work-related interstate, back road and city driving, the 748 put out 55 miles to the gallon on a regular basis.

So far, so good.

On the street, the Ducati was everything I had ever dreamed of and more. For the first time, cycle magazine phrases, like "useable power" and "stable chassis" made sense to me. Although I was worried about a motorcycle that had set for two years, the 748 turned out to be dead-on reliable, starting with the first press of the button, even on freezing winter mornings.

The Ducati's racing pedigree even seemed to enhance certain aspects of its maintenance. It field stripped like a machine gun, with parts coming out in chunks, for easy access, cleaning and repair. Dry clutch maintenance was simple. Beginning with the Hawk, I had come to find a single-sided swingarm to be the most practical feature a motorcycle could have, making chain, rear brake and rear wheel maintenance a snap.

Bike Week 2005 would provide the ultimate practicality test. Though most of my riding is local, I take the occasional road trip, and to earn the right to stay in my garage, the Ducati would have to be up to traveling. Would a superbike make a super sport tourer? Like the Hawk, I wanted everything from the 748. It had proved manageable as a daily commuter, but could it, and I, go the distance? I remembered working at the local motorcycle shop one day, when a group of out-of-towners pulled into our lot on a mixture of 748s and 916s.

"Have you ever ridden one of those things," the sales manager said, snapping me out of my mouth gapping, nose-pressed-against-the-showroom-glass trance? "They're a torture rack."

Working at the dealership, I had seen many riders try to turn their machines into something they were not. A guy would fall in love with and buy a VFR and then, within a month, began to feel that because his bike had a full fairing it should be the fastest thing on the road. Two thousand dollars later, when all of the practical, all-round features of the VFR were gone, kids on fur-covered ZX-6s were still smoking him at stoplights.

Modern motorcycles come from the factory with a very narrow focus. A V-Strom is not an enduro. A Goldwing is not a drag bike. Trying to turn these motorcycles into something they're not usually just does away with the qualities that made them such a great bike to begin with.

I was sure that the 748 could be modified into a touring bike, but touring wasn't my primary focus. If it was, I should have bought something else. In stock form, the Ducati was perfect on the back roads and city streets where I spent most of my time, so I wasn't about to change anything. The question that I was seeking an answer for was "can I occasionally go touring on a basically stock superbike?"

Before the Daytona trip, my longest continuous ride on the Ducati had been around 150 miles. I had developed a riding technique that involved wedging my knees into the tank's indentations, like the bucking roll on a western saddle, to take the weight off my arms and wrists. On long straights, I could rest my elbows on my knees and tuck in behind the wind screen. It was confidence in my ability to go the distance on the Ducati that landed me on the interstate, heading south to Florida, in the midst of an early March ice storm.

Nearly two hours into my journey, as I neared Roanoke, Virginia on Interstate 81, the skies began to clear and the roads turned from slick to wet. Up ahead I could began to see the sun peeking through the clouds.

On my first tank of gas, the low fuel light didn't begin to wink on until the 200 mile mark. Throughout the trip, the Ducati turned in fuel mileage numbers between 60 and 70 miles to the gallon, good for a theoretical range of nearly 300 miles. I only ever pushed it to 250 miles, but even at these stretches, I was in the saddle for about three and a half hours.

My discomfort level quickly plateaued at "mild" and never got any worse. I was using my "sportbike yoga" technique, alternating through a series of positions that held one part of the body in tension, while letting the others relax. By the end of the day I could feel fatigue in my arms, back and shoulders, but when I begrudgingly pulled off in Waxhaw, North Carolina, I felt like I had several hours of riding left in me. The torture rack was treating me well.

The weather was perfect the rest of the way. I got into Florida late Sunday afternoon with enough time left to wash and wax my bike back to trailer fresh condition. On Monday morning, it was off to the Speedway and Main Street.

The traffic on Bike Week's main drag was the perfect practical ride torture chamber. In the sluggish parade of one-mile-an-hour travel in 90 degree weather, the Ducati's temperature gauge quickly pegged as I used blip-and-slip clutch manipulation to keep from stalling. The 748's speedometer starts at 20-miles-an-hour. The bike really isn't meant to be ridden slower than that. When traffic ground to a halt, I turned the Ducati off to let it cool until things started moving again.

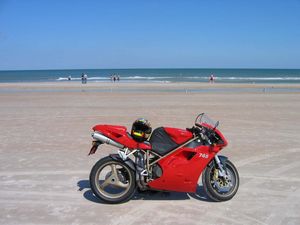

Hitting the beach, I spun my way through the rutted ramp. I wasn't about to spare the Ducati from any of the Bike Week festivities. I convinced a rider from Pittsburgh on a custom Shovelhead to snap a picture of me and the 748, using the ocean as a backdrop to capture the two of us in a rare island of solitude in the midst of a crowd of half a million.

I started back on Saturday morning and by the Georgia line, nearly all the bikes heading north were on trailers. The Ducati continued to excel at what it does best, getting from point A to point B as quickly as possible and never missing a beat. Its reliability made the return trip into an uneventful mix of billboard scenery and convenience store gas stops.

Within a year of having the Ducati back on the road, I added 15,000 miles to the odometer. The cost of parts and maintenance proved reasonable. I had been warned that these race-bred monsters would eat chains, sprockets and tires for breakfast. Granted, a base model 748 is the scrawny kid brother of a 916SPS or 996R, but consumption of expendables is acceptable. I pushed a rear 208ZR to 7,500 miles, though I toasted two fronts in the process. The chain and sprockets have outlasted several sets of tires.

My trip to Daytona was merely a personal accomplishment, icing on the cake of my first Ducati ownership experience. I'm sure that plenty of riders have made longer trips in more difficult conditions on less practical machines. But I learned one thing; you don't have to be a rap star with a dozen bikes in your garage to enjoy a wide range of motorcycling experiences. Also, you don't have to compromise the features you really enjoy on a motorcycle for the sake of practicality. It's something to consider when you start thinking about a new motorcycle. Find the bike that is the best you can afford for the type of riding you do most. Try using it for things its manufacture never intended. Maybe even take it on a trip. You might be surprised. The 748 made the grade. I think I'll keep it.

More by Jeremiah Knupp

Comments

Join the conversation