Erik Buell Interview

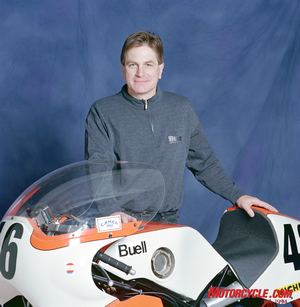

Erik Buell, the Chairman and Chief Technical Officer of the company that bears his name, is the kind of guy who makes a great conversationalist about all things motorcycles.

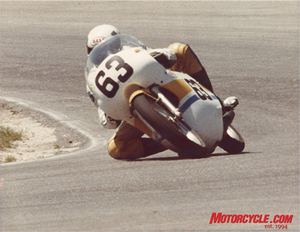

He was a real-deal racer, competing at Daytona racing a fire-breathing Yamaha TZ750 against riders such as the legendary Kenny Roberts. And in case you think Buell’s theme of putting a hot-rodded Harley engine in a sportbike chassis is a fairly new thing, consider that Erik Buell created his RR1000 Battletwin in the mid-‘80s, a Harley XR1000-powered sportbike with modern-day Buell innovations such as an under-engine muffler and shock absorber.

Back in 1979, fresh with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Pittsburg, Buell talked his way into a job at the then-struggling Harley-Davidson, turning down lucrative offers from Pratt & Whitney, General Motors and Black & Decker. During his time there, he was still racing and was in the midst of developing a 750cc two-stroke Formula One racer, eventually taking a leave of absence in 1983 to pursue bringing his bike to market. Well, the AMA put the kibosh on the F1 class that year, and with it went Buell’s prospective racebike business.

After running out of the XR1000 motors for the above-mentioned RR1000 Battletwin in 1988, Buell followed it up with the Sportster-powered RS1200 Westwind. But the Buell company burst into a new era with the 1994 introduction of the S2 Thunderbolt. Its tubular-steel frame provided the basis of an expanding lineup, including the attention-getting S-1 Lightning. Then the aluminum-framed XB series debuted in 2002, ushering in a new age of Buells, now lighter and more reliable than ever. All (except the single-cylinder Blast) were powered by high-performance versions of the air-cooled, pushrod V-Twins found in H-D’s Sportster line.

But now comes the Buell that sportbike aficionados have been asking for. It’s the 1125R, and it’s packing liquid-cooled heat for the first time with a fully modern and tidy proprietary V-Twin.

On the eve of this new era, we thought it would be interesting to chat with the man behind Buell’s innovation and expansion, so we dialed up Erik Buell for a chance to get his thoughts in front of our reader’s eyes.

Motorcycle.com: It’s a big year for you and your company.

Erik Buell: It sure is. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time, and we had to get ourselves in the position where we can do it and do it right. And – whew! - it feels really good.

MO: At one point in the past you had told me that Harley wants to operate Buell as independently financed – they didn’t want to throw a bunch of cash at it. Is this how it’s happening? Is Buell making money and is that where the money came from?

EB: The money’s being reinvested. What Harley did was invest money in Buell to get us going, and then they wanted us to be able to establish ourselves and take care of most of the growth internally. They supported us a lot, but they’ve tried to keep us from becoming a toy or something they would just throw money at it and experiment. The answer is we focused on business, which is really good for us, because then you start thinking about long-term and are we going to make this happen. Initially there was a little bit of interest in experimenting a little and using Buell as a kind of R&D concept place. But then it turned around and we needed to establish ourselves as a division. The bottom line is that you can reinvest in yourself – they’re not asking for money back into the corporation to be split up between shareholders and that kind of thing.

EB: Yes, it’s expensive, and it’s a significant investment. This specific project is a little over three years old. The concept of doing a high performance, high-tech, water-cooled bike to add to our current lineup has been there for quite a while. How to do it and make it work took us awhile.

MO: The previous Buell mantra has been air-cooled, light weight, simple. The 1125R is a step away from that.

EB:Yeah, it’s a different customer. There’s some really nice things about that (air-cooled) engine and we knew there was a group of customers who liked a blend of heritage and simplicity, but they’re also into sportbikes. We thought that the Harley-based architecture design, especially if it was redone like we did with the XB, would make a pretty good engine for that kind of guy. It’s paid off for us, paid the bills, and got us to invest to grow in the business, and made a lot of people happy with those bikes.

That’s still a fundamental part of our business, but it’s a different group of customers. They’re a very loyal, niche group of customers, which is good, but they are not the majority of sportbike customers. And we knew we needed to do water-cooled bikes for those who weren’t into the (air-cooled) heritage.

MO: So if this is a different customer, who do you think these new customers are for the 1125R?

EB:I think that there’s some similarities with what our current customers are, but the people they we are going to appeal to with this bike are going to be more experienced riders, just because, at that kind of pricing level, it’s not an impulse-buy item, and it is different than others and it’s not a commonly known brand name. So we know we’re not going to be the guy who just heard about a sportbike and decided to run out and buy one – that’s the Honda territory or whatever. But for people who have owned bikes for awhile, we think we’re going to offer them a very good choice. The difference between these customers and the current ones are these are people who want technology in the engine, and we know that’s the majority of people. Now, we could argue the point that air-cooled technology is pretty cool it its own way, but there’s a lot of those people who just aren’t there and they’re convinced water-cooled is superior and they want more power per cc. They’re certainly entitled to their opinions and we think they’re valid for them, so we thought we’d do a bike for them.

EB:That’ll be interesting to see – I don’t know what current products they might be looking at or where they’re coming from. Hopefully we’ll bring more people into motorcycling – people who maybe haven’t bought a sportbike for awhile. You know, they have their sports cars as well and whatever else they have, but they’re into technology. And we may get some people in from other brands. There are a lot of very good motorcycles out there, but I really think we have a world-class alternative finally.

MO: And what is riding this bike like for you?

EB: It’s very fun – it makes me feel very young again! (laughs). Since I started riding one of these things and put miles on, I’ve lost 20 pounds! I realized I needed to get a little more athletic to go along with this bike!

MO: So you literally lost 20 pounds?

EB:Yeah! Literally! Man, I’m working a little hard on this bike and need to get a little more fit. I had it down at a test track, and as the laps went whirring around, I got a little more forgetful of who I am and more into the fantasy of who I could be. I had huge, big, major opposite-lock slides in this corner out onto the straightaway, totally controlled. (laughs) And then I went into the pits and said, ‘I think I’m done now.’

MO: I’m guessing that for a significant project such as this, it all revolves around the motor at first, right?

EB: We co-designed the whole thing from the ground up, so it’s an all-new engine and an all-new chassis. This is really ground zero, because BRP (Bombardier Recreational Products) does enough of different engine types and their equipment is more flexible, so they could really do anything we wanted with the engine design. So we literally co-designed the engine and chassis at the same time.

MO: I’m interested in how you co-design such complicated components. You’ve got some parameters you give Rotax and they come up with something from there? Like, bore and stroke, is that set by you guys?

EB: What we were given was the chassis interface points and the rider needs and the overall performance delivery things. So, for example, when you talk about the bore and stroke, that came from them. But the bore and stroke came from them because we gave them the parameters we wanted. We wanted over 80 foot-pounds of torque starting at 3500 rpm, but I want engine to run to a 5-digit rpm – I want to be able to go over 10,000 (rpm) with it. Those are things we think the customer would want from a Buell – the neat powerband that people love of the (XB)12s but without ever stopping. We needed a very wide, flat powerband that would go out to there, and we needed a certain horsepower level. So we gave those parameters to them and said, ‘What will deliver this?’ And they came back and said, ‘Well, if you’re running 1000cc, this will make it difficult.’ And I said I don’t care about the stupid superbike rules – what does it mean to me (laughs)? And it’s funny, the (superbike) rules changed anyhow, but that was never part of equation. It was about what we want for the customer and what it would take to deliver it.

Then on the engine design layout, there was a lot of discussion over the Vee angle and the right package and what we needed from a chassis standpoint and what we needed for the power delivery, which is what rolled into the 72-degree configuration. It was a very fun project. Like the integral dry sump on the motor, where it would be located, where the mounts were going to be and where we wanted the output sprocket of the engine to be for the right chassis geometry, and how the engine stiffness needed to be. So we were going back and forth with FEA (Finite Element Analysis) models. Since the engine an integral part of the chassis, the engine stiffness needed to be part of the matrix to get the ideal chassis stiffness.

MO: Since you’re such a tech-head, we imagine you were in heaven during this development?

EB: (Giggles) Yeah, actually. I’m that combination of a guy who really loves to ride and also loves the technology to get you there, so it was fun. And working with Rotax was really cool –they’re very good, cool guys. Actually, the lead guy on this project is a guy who did his internship at Buell – he worked at Buell for about three years, a German kid who went back to Europe and went to work for Rotax. That was really neat, and then the head of Rotax right now was the director of engineering there, and he’s a brilliant guy and he and I get along really well, so that made it very fun.

MO: Being a racer such as yourself, you must’ve been tempted at one point to build a bike you could race.

EB: Well, we always have to put that into perspective. I love racing and I’d love to do it, but on the other hand we have to pay the bills, we have to do the right thing to deliver the bike. At the moment it’s not in the cards – they keep shuffling them (laughs). We believe, foundationally, we have a product that could be raced. It’s just a matter of putting things together and coming up with a race program, but fundamentally this bike is capable of it.

EB: It is not scheduled to be a major part of the marketing tools. We’ll continue to do the stuff that we’ve always done, which is to put up a lot of contingency money, especially for the size that we are, and encourage privateers. But, as far as full factory effort or anything, nothing like that is scheduled. Even though the engine is an 1125, if we had decided to put a race program together, you could’ve made a 1000cc version, or I suppose you could make a 1200cc version. But it all has to be fundamentally spun into the business package – you know, is that fundamentally something we could afford to do? Maybe one of these days that will happen. When we were talking to Jeremy (McWilliams) and some of the other test riders, I sat down with him and looked him in the eyes and said, ‘Okay, Jeremy, if some magic happens and we go World Superbike, what do we need?’ And he said, ‘Nothing but power, Erik.’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s what I wanted to hear.’

MO: You guys have always come up with creative names for your bikes, but on this one you decided to use just the displacement. Why is that?

EB:We had names for it, but we ran into a situation where a lot of people who have grabbed a lot of the names up and used them, sometimes very little, but they have ownership of them. So there was a big debate about this with the legal community, and they kept coming back and saying, ‘I don’t know.” And I finally said, ‘To heck with it.’

MO: How about Helicon, the name of the engine in the 1125R?

EB:Ha! That was one name they didn’t have a problem with and they wound up sticking in. It was a code name we had for the project, and the marketing guys still wanted to do something with that, and this was one that never bounced off anything because nobody ever used it. Helicon was the stream of water that flowed from Mount Olympus when Pegasus struck it with his hoof, and it was the spring of water that came down that was the fount of all knowledge. So, since it was a water-cooled engine and was the code-name given the project…

MO: This new motor, it seems like it shares a few design aspects of the Aprilia/Rotax 60-degree V-Twin, like the counterbalancer arrangement and slipper-clutch action.

MO: Is the slipper clutch mechanism in the 1125R similar to the Aprilia?

EB: I believe it’s based on the same theory. I think it’s not an Aprilia thing, I believe it’s a Rotax patent. So the concept is similar. It’s a pretty neat concept actually. The wear is almost non-existent. On high-torque Twins, mechanical slipper clutches really get beaten up a lot, and this doesn’t, so that’s kind of cool.

MO: Was it possible to use the swingarm for the oil reservoir?

EB:We could’ve, but it would’ve meant external oil lines. Since we were doing an engine from scratch and we could build it in the engine, we decided that it’s more compact with less parts and follows Buell’s philosophy – make one part do two jobs or three jobs.

Normally, you have a wet-sump engine, by god, and there’s the sump at the bottom of the engine. And we have a dry-sump engine and you mount this thing somewhere else. Well, we used to have an aluminum tank for that, and then we got smart and made the swingarm to the job. And then we looked at this and said, ‘If all these things have oil lines, why don’t we put the dry dump in the engine?’ ‘Oh, you mean a wet sump?’ ‘No, no, the dry sump in the engine – you put the feed lines internal in the engine and they go over to this dry sump so it’s separate and doesn’t get turbulated by the crankshaft.

MO: Sitting on the 1125R, with its higher clip-ons and fairly comfortable posture, doesn’t feel like an ultra-sportbike. Can you tell us how you decided to make a bike that is racy but not super racy, something for the street.

EB: That’s kind of the real-world philosophy we have had. If you really want to ride on the street – you know, ride quickly, ride a high-performance, high-technology bike. So, do you want to ride a race-replica, or do you want to ride an incredible performing streetbike. They’re not necessarily the same thing.

MO: I imagine you expect a bunch of these bikes to take part in track days?

EB: Oh yeah. And I think they’ll be real, real quick. And you’ll find that the extra 3 inches higher of your butt in the air (like on a race-rep) won’t mean anything on a track day. It might be worth 5 mph at Daytona, and in the hands of Miguel Duhamel that’s worth something. But for even a really fast rider at a track day, it doesn’t matter. And the fact that you can crank in lap after lap and you’re actually spending all day there, you want to be comfortable and in control. All the racers who rode the bike love it. We did an endurance race as part of development and brought the guys in to ride it. They had a lot of fun and were saying, ‘Man, I’m just not getting tired! I can just ride this thing and ride this thing.

MO: You’re an engineering guy. What aspect of the 1125R are you most proud of?

EB:There’s no one thing that stands out – there’s so much good stuff on it. We’re still a tiny little team of people – young guys, just full of energy. I know the adversity of what we had to do to get this thing done, and just from one end to the other, it’s a treat. I know every person who was involved in the design of this part and guy who was involved in the design of that part, and what the issues they had and what the testing was that they had to go through. What’s impressive to me is the way the whole team worked together and kept changing things to get the balance right.

And it came out so that it’s comfortable and yet it’s really, really fast. It’s high-performance yet it’s forgiving and it’s easy to ride. It’s a really nicely done package. You know, there’s lots of great motorcycles out there, but this is one that I’m certainly proud of. And I think that anyone who owns one will really be proud of this bike.

Related Reading:

More by Kevin Duke

Comments

Join the conversation