Church of MO: Open Warfare 1996

Buell S2 Thunderbolt vs. Honda CBR1000R vs. Kawasaki ZX-11 vs. Suzuki GSX-R1100 vs. Triumph Daytona 1200 vs. Yamaha FZR1000

What do you choose to ride if you need to be in Denver tomorrow?

If you need a bike that will travel highway miles, but still leave a smile on your face in the twisties, and leave everyone else in the weeds? The choice may be far more difficult than you’d think. We gathered together the top open class sport bikes for a hunt through the canyons and freeways. Our quarry? That elusive best bike.This time, the answer may surprise you. So we’re going to leave it ’till the end, just to keep you on your toes.

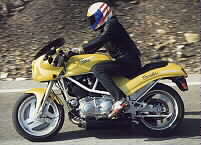

Sixth Place: Buell S2 Thunderbolt

What on earth is that doing here? Some testers questioned the Buell’s inclusion in the test. After all, every other motorcycle here has four cylinders and a whole lot more power. So, right there you have the primary reason for the Buell being at the bottom of the heap. But we felt that the made-in-America motorcycle (the only one in the test) would stand comparison with the rest of the superbikes, and in some situations, it does. On a twisty road, the torquey Buell will stay with the pack. When the road straightens out, however, the Buell is left flailing far behind as the four-cylinders head for the horizon.Fifth Place: Triumph Daytona 1200

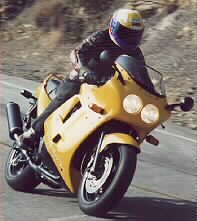

Biggest bike in the test, the Daytona is also one of the newest, having been around in the States only a year or so. We’ve been over Triumph’s recent history before (and so has everyone in the print magazine business), so let’s just say that history does not repeat itself. The new Triumphs boast high standards of quality control and Japanese standards of reliability. Triumph’s styling is second to none. The Daytona stood out of the crowd wherever we parked, largely because of its brilliant buttercup-yellow paint scheme. Combined with the satin black of most engine parts and ancillaries, the effect was striking. If you don’t like attention, don’t buy a Yellow Daytona! (They are, sources say, available in basic black for the shrinking violets out there.)

We wish it handled and performed as well as it looked: Unfortunately, hampered by the same frame as the rest of the range, the Daytona promises more than it puts out. The adjustable rear suspension just didn’t have enough adjustment to handle a sport bike pace. Cranking up the rebound damping to the max still didn’t quell the wobbles through the bends that the FZR and the GSXR sailed through (the Daytona still stayed ahead of the ZX11, though). The steel, spine type frame felt strong enough, but even after five model years in Europe and new suspension units for ’96, Triumph have yet to solve the suspension equation on this, their flagship sportbike.Given the biggest engine in the test, the Daytona had a size advantage over the opposition that didn’t make the transition to the streets. The Triumph uses a marriage of Japanese and European technology, and unsurprisingly the Japanese aren’t about to share their latest, state of the art information with the Brit competitors. Triumph engine designers, we are told, were guided by British car-racing specialists Cosworth. Pistons and rods are balanced to the nearest gram. The four cylinder motor runs two balance shafts. Yet vibration levels are on par with Honda’s CBR, higher than the FZR and the GSXR.

Another area where appearance promises more than the Triumph delivers is the brakes. The twin front discs run out of handlebar lever travel all too soon. Compared to the razor-sharp stoppers of the FZR and the GSXR, the Daytona’s brakes feel decidely second rate, in spite of the steel-braided hoses that now come standard. We were informed by an insider that the Triumph suffers from caliper piston o-rings that are too thick and cause the pistons to return too far into their bore. This explains the need for an extra pull on the lever. The riding position suits taller riders best; it’s a long reach across the tank to the bars. Compounding the problem, the Daytona’s seat is simply too far off the ground for smaller riders: Those of less than five and a half feet stature need not apply. For the rider who must have style before anything, the Daytona is the one. For ultimate performance, check it off the list.

Fourth Place: Honda CBR1000R

Honda’s biggest CBR is at the other end of the sport bike scale from the seminal CBR900RR, a bike only a few cc’s smaller, but radically different. Where the RR screams ‘racetrack’, the CBR 1000 mutters ‘road’. While the RR stops insurance brokers in mid sales pitch, the CBR 1000 gets sensible rates. When the RR pilot has to stop to massage his aching neck, the CBR rider passes, still comfortable on the all-day seat. The CBR rider also has the benefit of Honda’s linked braking system, which takes some of the sting out of panic stops for novice riders, although what novice riders are doing on a CBR baffles us.

You don’t put on miles by going fast for ten minutes, then stopping for twenty. The aim of the comfortable ergonomics of the CBR, the subtle but stylish graphics and the effective (but heavy) combined braking system is to attract the non-squid. Honda’s big sporty is aimed securely at the mature sport rider. The kind of guy who knows that to get there, you have to put on the miles.Underneath the CBR’s all-encompassing bodywork lies a thoroughly sensible, conventional, double overhead camshaft four cylinder motor. One of the smallest engines in the test, it displaces 998cc, makes do with four valves per cylinder, is of course liquid cooled, and sports a relatively modest 10.8:1 compression ratio. Nothing, in other words, that will set the world on fire. Compared to the magnesium and other exotic materials used in the Suzuki, the Honda’s bill of fare is pedestrian. It did however come with near-perfect jetting, a rare commodity in new motorcycles these days. Only one other bike in this test didn’t have a lean surge or off-idle hesitation. The CBR’s motor tied with the Triumph for intrusive engine vibration though. Conventional forks with 41mm tubes keep the front 17 incher away from the steering head at a conservative 27 degree angle. The frame, unseen under the plastic, is of steel, as is the swing arm.

Most radical part of the CBR’s make up is the linked braking system, which operates through an involved hydraulic network that’s about as complicated as Tokyo’s subway system, but makes just as much sense and is just as efficient in conveying a vast mass of motorcycle from speed to stasis. At slow speeds, however, the over-zealous brakes make gentle stops difficult.If all the above sounds uninspired… 100% guilty. The CBR is boringly familiar, undramatically capable of transporting rider, luggage and passenger too in relative comfort over large areas of the country, preferably the corrugated bits.

It’s been around for years, it’s reliable, has an effective turn of speed, but unfortunately an almost total lack of charisma. Get off at a rest stop, and sometimes it’s difficult to remember how you got there. If this is the kind of relentless reliability you need, go for it. It’s a middle of the road, middle class motorcycle, so we’ll score it more or less in the middle of the pack.

Third Place: Suzuki GSXR 1100

All engineering is a compromise. Tell that to the GSXR rider. There’s little compromise about this machine. It’s an out and out big-bore sport bike, with little thought of comfort. Or so it would seem until you actually ride the Gixer over large expanses of blacktop. For the average human, the seat is broad and flat, the footpegs, though high, are reasonably well placed, and the clip-on style bars stretch the torso just enough, yet not so much as to cramp into cro-magnon position. As long as you don’t attempt several hundred consecutive miles of straight interstate, the GSXR is a competent enough sport tourer, especially with a well-filled tankbag to rest your torso on. It’s on those twisty bits between the interstates though, that the GSXR 1100 excels. Point this weapon at a succession of curves, and what follows is pure adrenaline.

The biggest Gisxer has been around since 1986, and through a massive number of changes since then, including the change to liquid cooling (with associated weight gain) a couple of seasons ago. The perimeter frame is still around, and starting to show its age: Likely it’ll follow the GSXR 750 model and change to a twin spar design soon. But it still works quite well enough, thank you. Suzuki beefed up the chassis and lowered the weight of the 1100 last year, while adding some of the best brakes around. Magnesium parts abound, but no effort was spared in the braking department. The twin six-piston calipers give awesome braking, and superb street feedback when combined with the Dunlop D202 radial tires. One finger braking from 100 mph is easy, and feels safe and secure.

Handling is razor-sharp. The 43mm inverted forks are suitably massive, yet are lighter than the 41mm units that preceded them. A nudge on the bars to tell the bike where to go, and you’re there. In the twistiest of canyon roads the 1100 won’t pull away from a well-ridden 600, but once those corners open up, it’ll pull away from just about anything, excepting a well ridden FZR 1000. Suspension is fully adjustable, front and rear, and we found ourselves fiddling with the adjusters quite a bit, to get the optimum settings, which varied from rider to rider. Another item on the engineers to-do list last year was to broaden the power band. Substantial changes to the cam timing and ignition yielded bigger horsepower numbers in the mid-range, between 5-10,000 rpm. The real world range, you could call it.One retrograde step was the fitting of a squid sensor in the gearbox. This little device retards the ignition above 6,000 rpm in first gear, preventing squid-identifying powerband-induced loops. Sources tell us it can be overriden, restoring all the lost power in first. We’re not allowed to tell you, however that disabling the offending device is as easy as disconnecting the red wire from a two-wire connector behind the right side panel. Though last year’s changes did result in 10mm lower footpegs, the ergonomics are still definitely on the sporting side. In other words, long distance rides are only for those with strong wrist, forearm and neck muscles, or those that want to develop them.

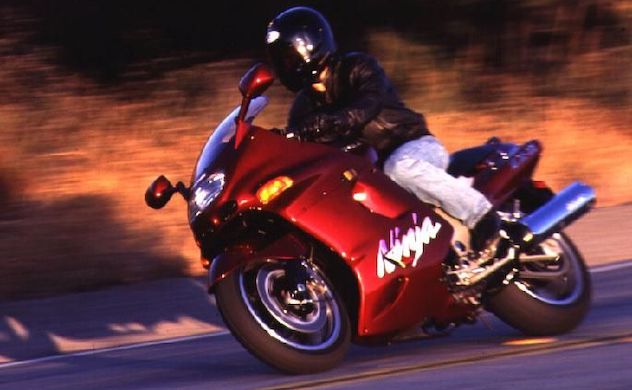

Second Place: Kawasaki ZX11

Motorcycles just don’t get any more fun than this one. Even in traffic, there was almost always a big smile under the chinbar of the ZX11 rider. That smile only disappeared in the twisties. The ZX is the 28 pound sledgehammer of motorcycles. Subtle it ain’t. After most of a decade, this is still the fastest, baddest bike around, and you’d better remember it. Opening the throttle, at almost any speed, in any gear, results in a rush of acceleration that tugs your arms forward. No matter what speed, what gear, there’s still plenty of power left. This monumental, excessive amount of power generates the smile.

The ZX’s reputation as fastest motorcycle in the world derives as much from its outstanding aerodynamics as raw power. But even down low in the rpm range, the ZX responds with brute force

whenever the throttle is opened. In the midrange, there’s simply nothing that comes close to the ZX. The motor’s good enough to make you forget the spongy forks, the bouncy ride and the generally poor handling, when compared to the other, more flickable bikes in the test. You simply can’t run the ZX into a corner at the same speed as the other sportbikes: It will shimmy and wobble in protest, and would scrape its pegs earlier too, if the high-mileage tires were sticky enough to lean the bike over that far.

Throw a few curves though, and every other rider (including the doughty Buell’s pilot) was bound to pass. But when that road opens out, the purple mile eater simply gobbles up the competition. Nearest rival is the GSXR, with only slightly less power on tap at peak (horsepower numbers for the ram-air equipped ZX were achieved without the benefit of a 180 mph headwind). But at any other rpm than full, the ZX is just so much torquier. The Suzuki’s power curve dips in the mid range, while the ZX simply climbs, and on the road this shows up as the GSXR becomes a smaller and smaller blur in the ZX’s mirrors. Having an extra gear than most other bikes in the test helped, too, although the gap between fifth and sixth was minimal, and sixth can be used as an overdrive. Do this, and the ZX is capable of astoundingly good gas mileage — getting over 50 mpg is easy. All this, and an almost total lack of vibration through the rev range, make the ZX the smoothest bike on test.

It didn’t come that way stock however. Carburetion was less than perfect — in fact it sucked. A lean spot at 4,000 rpm would cause the bike to slow down when the throttle opened up for the exit of a corner or a quick lane change on the freeway. A local Kawasaki mechanic informed us that the problem could be fixed under warranty as a driveability problem cure, so we felt that shimming the needles ourselves wasn’t really cheating. The result was definitely worth the effort. Throttle response improved immensely and vibration disappeared.

The relaxed ergonomics, with relatively high mounted, gently angled bars, low buttock-hugging seat, narrowed frame rails between the rider’s knees and comparatively low footpegs give the ZX a comfortable riding position, most comfortable of the lot for all day criusing. About the only complaint for some — apart from the atrocious handling — is the style of the thing. Painted toe to tip in a muddy plum color, with tacky chrome stick-on tank decals, the Kawasaki is not only the fastest bike in the world, it’s the dowdiest one too. Although there were some that appreciated the lack of racer-boy graphics.

The Winner: Yamaha FZR 1000

Nine Years At the Top Number one after all these years? Surprisingly, astonishingly even, the answer is yes. Yamaha’s 20 valve FZR doesn’t look a lot different from when it was introduced back in 1987, but the years have been kind to it, and it still outhandles, outbrakes and outpowers many newer motorcycles. It’s still the best all-round heavyweight sportbike there is, not because it excels in any one area, but because it offers the best overall performance package.

Radical when it came out in ’87, the FZR’s motor is still a technical tour de force. The cylinders are inclined to give the incoming mixture a straight shot at the three thimble sized inlet valves, and 38mm carburetors control the flow. Medium and low end power is boosted by Yamaha’s EXUP exhaust powervalve, which adjusts header pipe volume via a solenoid-operated butterfly valve. As aftermarket exhaust makers have found, it’s difficult to beat this system. While the FZR doesn’t stop quite as well as the Suzuki, it’s close; the six piston calipers and semi-floating discs give strong, linear retardation without excess effort. The FZR owner can argue that his bike brakes just right: the Suzuki is over-braked, he can assert with fervor.

And while it doesn’t twist the rider’s arms out of their sockets quite as much as the astonishingly quick ZX11, somehow it’s never that far behind on the street. The FZR’s compact engine still packs a respectable punch. One advantage of an engine in the liter class is that you don’t have to play tunes on the gearbox to get the best performance: There’s enough power for overtaking maneuvers without banging down a couple of gears. When you do cog down, the power kicks in above 7,000 rpm, and builds all the way to the 11,500 rpm redline. Vibration rears its buzzy head at the high end of the rpm range, but it’s never overly intrusive. Carburetion was the best of the lot, too. Over the last decade, the FZR engine has gained an enviable reputation for reliability. The five-valve-per-cylinder design may be complex, but it stays together over impressively high mileages. Yamaha claims valve inspection intervals of over 26,000 miles.

Clinching factor in the decision to award the Yamaha the number one plate is the Deltabox chassis. Yamaha pioneered this frame, now the other guys have all copied it. Externally, the frame conveys a massive solidity that is responsible for its excellent stability. Complete with 41mm inverted forks, tapering-section swingarm and one of the best sorted suspension systems out there (due in no small part to Yamaha’s purchase of the Swedish suspension gurus Ohlins), the ride is superb. It steers more precisely than the GSXR, which is high praise indeed. The massively solid chassis belies its weight in the twisties: It simply feels like a smaller bike. The suspension doesn’t exhibit any of the vices most other bikes in the test displayed. Up front, Golden Gate-like solidity comes from the flex-free inverted fork. It lacks any damping adjustment, but then again it doesn’t need any, for our riders. At the rear, the single shock does have an adjustment for rebound and compression rates, but we tended to leave it alone: The factory setting worked just fine for most riders.

When it comes to day-long rides, the comfort level isn’t the best, but it’s far from the worst. It all depends whether you fit. Long-of-torso riders may find themselves cramped for space, long legged riders will find their extremities sticking out below the tank. But those riders whose knees actually fit in the tank cutouts will find it comfortable indeed, if not on the interstates, at least on the backroads and blue highways. The clip-on style bars are too low for optimum touring comfort, but are just right for attacking the twisties.

There you have it. You don’t need to be top everywhere to be the best. A well balanced, all ’rounder can win. If the Yamaha does have a fault, then it’s a certain appliance-like lack of soul. Otherwise, the package is difficult to beat.

Impressions:

1. Andy Saunders, Editor

What’s Nirvana? Give me a few hours of good weather. Give me a sportbike and a road that unwinds like a politician’s campaign promises. And give me someone else’s driving license (Hey, Len can I borrow your Florida license today? ‘fraid I lost the New Mexico one yesterday, but I’ll pay you the $10 filing fee for it).

Every motorcycle in this test is easily capable of putting its rider in motorcycle Nirvana. Some riders don’t want Nirvana (turn that CD player off, Todd, dammit), but if you do, the choice of mechanized drug is up to you.

My favorite? Well, I’d like the ZX11 for a wake-up call on Monday, the FZR for getting into the swing of things on Tuesday, the GSXR for some heavy hitting on Wednesday, the Daytona to brighten up the Thursday blues, and the CBR to head out for the weekend on a Friday afternoon. Oh, and the Buell to take up to the Rock Store on Sunday afternoon.

2. Brent Plummer, Editor-in-Chief

Suddenly, like a white and blue bolt of lightning from out of the darkness, I saw the light. You see, for months I’d been calling Graphic Designer Mike ‘Speed’ Franklin crazy for taking a Yamaha FZR1000 several thousand miles through the open American West. But after one twisty canyon mile onboard the FZR1000, I stopped doubting his sanity, and instead started wishing it could’ve been me winding through high mountain passes, thousands of miles from the office and miles away from any modern communication device. When the going gets twisty, no open sportbike compares to Yamaha’s biggest.

But would I buy one? Probably not. What I want is this: The power and comfort of the ZX-11, FZR1000 handling (perfect out of the box for my 5’10” 170-pound size), Triumph’s stunning good looks and Buell’s Sportster engine go-fast parts availability and pricing. Wrap that all together, and what do you have? A Suzuki GSXR1100. It’s not the fastest, it ain’t the best handling and it sure looks goofy parked next to the Triumph, but it’s the best overall compromise and has the most potential to keep me happy as time passes and years slip by.

3. Mike Franklin, Graphic Designer

It came as no surprise to me. I’ve been a fan of Yamaha’s FZR 1000 since I bought my first one in 1987. When the 1989 model came out with all the fanfare and praise, I bought one of those, too. In the ensuing years, I haven’t ridden anything that would make me want to give up that ’89 — until I rode the ’95. The upper fairing is wider so the mirrors actually show what’s behind you and not what you’re wearing, and the bars are wider apart too due to the bigger stanchions of the upside-down forks. Consequently, steering effort is reduced and cornering is mind-numbingly easy. Other than that, there isn’t much between the two bikes. Riding the other bikes in the test was an eye-opening experience. I wouldn’t have believed the amount of power that a motor was capable of producing until I experienced the ZX11 for myself. Unfortunately the ride doesn’t match the motor. Now if I could just fit that motor in my FZR…

4. Todd Canavan, Associate Editor

I have always wanted to ride the ZX-11. I had to see for myself if all the raving about the motor was true. It is. Unfortunately, the rest of the bike doesn’t live up to the standards set by the motor. Even though the Yamaha won the test, I didn’t enjoy it as much as everyone else did. My lanky ass just didn’t quite fit on it. The GSXR 1100 was the most enjoyable for me to ride on an every day basis. A tank-bag and a set of detachable saddlebags, and the GSXR 1100 could keep me happy for quite a few miles. It amazes me though that bikes that, for the most part, are nearing 10 years old are as competent, and competitive, as they are today.

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

For several years I enjoyed a ZX-11C, the all-black version which closed out the original ZX-11 lineup. Bad handling? No, not at all. It was more physical to ride than friends' 600s but The Eleven's very good steering and feedback made it a pleasure to push on backroads. The Eleven was noteworthy for the offhanded ease with which it exceeded The Ton, in fact all that was required was to relax and you were there! I never "made" it go over 100, I simply "let" it. Cruising at a buck-twenty felt so natural and safe. Which way to the autobahn?

I owned at 1200 Daytona, Buttercup yellow and enjoyed the heck out of it! FAST and comfortable a bike as I have ever owned. I little fat maybe, but a real torque monster. I rode with Harley guys and could leave them at will without downshifting. The Bike was a V-max in yellow for me. Rode 400 miles to my dad's house with ease in a long summer afternoon, Chicago to Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Love the thing, wish I would have kept it when I moved to Florida. Ahhh... good memory for me.