Church of MO: 2012 Honda Fury Vs. 2011 Yamaha Star Stryker

Today’s Church of MO intro has nothing to do with the Honda Fury or Star Stryker, but some might like to know that in searching through the archives, I came across some entries by The Highwayman in the old MO Forums, this one in reference to a story about Keith Code’s California Superbike School:

Teaching the Rules of the Road

Pumping brakes over a daunting mountain pass and pumping fists in a clear-the-house brawl. Grappling big chrome bars through a treacherous canyon and grappling atrociteurs to the death of their game. Defying the laws of physics by masterful roadcraft and defying those who pledge allegiance to the far-eastern feudalism of godforsaken lands.

This is how motorcycling is taught on the American highway.

The rules of the road here are set by stout and hearty men who enforce justice the old fashioned way. These rules are unspoken by words, but readily stated otherwise. Those fortunate quick learners need no more than a slight scowl, steely glare or arched eyebrow to figure it out. Others are richly deserving of a more painstaking education borne of boots, fists and fury. And then there are those who are given no more chances at getting it straight.

It is best to set upon being a quick learner.

They call me . . . The Highwayman

The Highwayman left the building as mysteriously as he appeared, no one save possibly a select cadre of stout and hearty men in chaps knows his whereabouts today. But that’s not important right now; what’s important is that the Stryker was one of our favorites, AND Road Test Editor Troy has promised us a Honda Fury review soon. Take it away, Dain.

Chopper Lite Shootout

2012 Honda Fury VT1300CX

First thing’s first, so let’s cut to the chase: choppers give credence to the old saying, “form over function.” Foremost, choppers are about style and being (and looking) cool. Long wheelbases, enough chrome parts to outshine a 1958 Buick Roadmaster, and laid-back ergonomics create a ride that looks oh-so cool. Handling, braking, even acceleration performance are secondary.

Based on its form alone, the Fury scores highly. Viewed from 10 or so feet away the Fury, straddling an incredible 71.2-inch wheelbase, appears to be a bike that was hand-built by someone who knows his craft.

The Fury’s sexy silhouette has all the lines you expect in a high-neck chopper: an extended front end creates a spacious void that allows the engine to be a predominant aesthetic fixture in the overall package, the exhaust system follows the bike’s lower lines such that it blends gracefully alongside the rear disc brake, and most of all the svelte gas tank’s curves flow from the frame’s backbone into a sculpted seat that practically melds with the Fury’s seductively large rear fender.

The frame rails are clean and purposeful, too, as if Honda’s workers employed the age-old trick established by early chopper builders, using plastic body filler to conceal unsightly weld joints. Oddly, though, there are a few weld scars at the top of the downtubes that could have been eliminated but weren’t.

Even the Fury’s 1312cc liquid-cooled V-Twin engine’s radiator is positioned neatly between the frame’s two downtubes so that the coolant hoses appear practically nonexistent. There is no ungainly radiator grille work, either; a small black plastic shroud is all that shields the radiator fins from road debris.

That’s not the only plastic component you’ll find on the Fury, though. In fact, if Honda ever ups the production run for the Fury, there’s a strong chance that the international price for plastic futures will increase, too. This bike has more plastic than a Lego toy. Both fenders, stylish as they are, are plastic, many engine cases and covers are made of specially chrome-plated plastic, and the chromed cosmetic side covers are made of that 20th century discovery, too.

Although the Fury’s plastic fenders are uncool for this class,” Ed-in-Chief Duke observes, “the Honda shows much better attention to detail, especially its high-neck frame, stylish headlight and very attractive wheels.”

Production costs no doubt played a factor in using plastic instead of metal, but liberal use of the lightweight material also helps keep the bike’s overall weight down. Strangely, though, while the Stryker relies on that old-fashioned material called steel to serve many of the same styling purposes, that bike weighs about 20 pounds less (663 pounds for the Fury versus the Stryker’s 646 pounds) than the Honda. The weight difference can probably be found in the drive-trains; the Fury has a drive shaft that requires abundant use of metal while the Styker calls on a lightweight synthetic-composite belt to transfer power to the rear wheel.

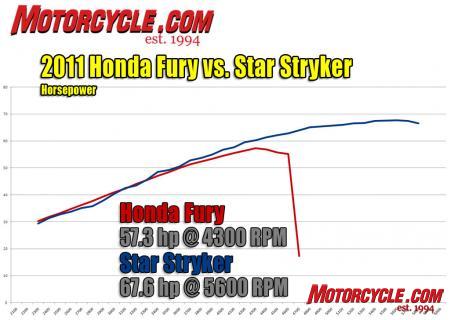

Styling and plastic aside, the Fury and Stryker share a common bond in terms of their engines’ pulling power, even though the Star’s slightly smaller V-Twin produces about 10 more horsepower on the Cycle Doctor’s dynamometer.

In top-gear roll-ons at 70 mph the bikes finished in a near dead heat. Not that either of these customs are road warriors in the performance sense, but their V-Twin engines pull smartly from near idle to their respective redlines. The edge in throttle response goes to the Styker, though, delivering a slightly snappier feel when rapping through the gears, but this comes with a small price of a herky-jerky feel at the throttle’s initial opening.

You can expect respectable fuel mileage figures, too, from either bike. Depending on how you treat the right-hand grip, miles per gallon figures range from the upper 30s to the low-to-mid 40s. Vibration is minimal, and the Fury’s exhaust note especially got our attention. True, the mufflers are visually thicker in their mid sections than what most real chopper riders prefer, but Honda had to deliver them to dealers as EPA-compliant cans, which accounts for their rather unsightly bulkiness. Even so, the Fury’s exhaust tone is pleasant and it gets your attention – you know, the way chopper pipes are supposed to do.

As noted, ride, handling and overall performance are secondary aims when it comes to building a custom chopper motorcycle. Same holds true with these factory specials, but after a ride across town or through the local countryside, the Fury and Stryker won’t disappoint you.

The Fury, especially, makes you feel like a bad-ass chopper bro. Swing a leg over its sculpted seat and grab the pullback handlebar grips, and first thing you notice is that your body assumes what can best be described as the “chopper slouch.”

You’ve seen it on chopper bros who have ridden by on their bikes – the rider’s back gently curves so that his head leans slightly forward, with arms reaching straight ahead, almost paralleling legs that rest their feet on forward foot controls. This posture has a magical feel about it, and you really don’t care anymore about how fast, or slow, you accelerate from the stoplight, driveway or local roadhouse. You just motor away, feeling oh-so bad and oh-so cool. You’re Peter Fonda, Marlon Brando and Sonny Barger all in one.

It gets better. When you roll to a stop and you place your feet onto the pavement, that cool feeling doesn’t dissolve and fade away. The lope of the Fury’s 52-degree V-twin engine entertains your aural senses, but you know the real show is the visuals that people curbside or in the car next to you are enjoying. You’re bad.

You’ll notice something else when you roll to a stop. The Fury requires steady pressure on the skinny brake lever and foot pedal to slow it down. Two-piston calipers (one up front, one on the rear) will properly slow and stop the Fury, but feedback is vague and uninspiring.

Now let’s talk about the Fury’s most striking feature, its extended front end. Choppers originally acquired their name because the builders attached extended fork legs to the bike’s triple trees. But doing so raised the front section of the bike, creating all sorts of handling issues. To regain respectable handling, the frame needed to be lowered at the front, and the solution was to cut – or chop – a wedge out of the steering neck so the builder could reposition (sometimes called “raking”) the fork angle.

Cutting and welding the steering head like that lowered the bike, plus it helped retrieve some of the lost trail, minimizing fork flop. This is a condensed version of what it took the chopper pioneers years to figure out, but in Honda’s case they simply determined what steering head angle (38 degrees) and trail dimensions worked best with the 21-inch front wheel, and then built the frame and fork length accordingly. Again, this is a simplified interpretation of what Honda’s engineers accomplished, but you get the idea.

“The Stryker’s 120/70-21 front tire offers more security than the pizza-cutter 90/90-21 on the Fury” Duke remarks. “The Fury’s narrow front tire gets distracted by longitudinal freeway rain grooves.”

Honda also managed to deliver a low seat height that places your butt just 26.7 inches off the deck. It’s part of the cool factor we talked about earlier, but it also should help sell more than a few of these bad-boy bikes to riders who are vertically challenged.

The lower seat height also helps maintain a low center of gravity. Coupled with proper steering geometry, this chopper is rather easy to maneuver around town. There’s no noticeable fork flop, and u-turns on a two-lane road are doable. There’s uneasiness to the Fury’s handling, though, when that long wheelbase encounters bumps and dips in the road, most noticeably while making or initiating turns. Be careful, too, about how far you lean the bike into the turn – the forward foot controls easily touch the pavement.

In terms of ride and handling, the Fury’s primary shortcoming is found in its suspension. Smooth road surfaces allow it to maintain a friendly ride, but a series of rapid bumps in the road often confuse the Fury’s damping rates, and you’ll experience some harshness from the fork. The ride won’t shake your dentures loose, but it’s not as pleasant as most cruisers. Perhaps we should check it off as part of the chopper experience and leave it at that.

And, indeed, the chopper experience is really what the Fury is all about. Its curbside appeal is striking, making you look and feel like a biker outlaw, yet this long bike will get you to and from your ride destination in relative comfort. In more than one sense, we’ve come a long way, baby!

“Both bikes deliver the requisite chopper profile, with V-Twin engines placed in high-neck frames and led by a tall front wheel,” Duke notes. “But the Fury pulls off the costume much more convincingly than the dowdy-in-comparison Stryker. However, the Honda’s pretty appearance comes at a hefty price.”

More by John Burns

Comments

Join the conversation

Ok, remember the procedure, coffee first, read second. Saw the headline and thought "They are remaking Airplane for Furries?"

Hey, Kevdashian!

http://www.motorcycle.com/g...

https://youtu.be/MlM8B8BbSYc