Top 10 Misconceptions About Motorcycle Suspension

All motorcycles come with suspension, and some of those components have settings that the riders themselves can adjust. That’s great if you know what you’re doing. Some bikes have a wide variety of settings for the rider to fiddle with. Again, if you know what you’re doing, the extra adjustments are a huge benefit. However, with the increase in adjustments available, the number of wrong combinations of settings also increases.

Now, suppose you add misinformation into the mix, and you’ve got a recipe for a foul-tasting suspension stew. In search of clarity, we turned to Ed Sorbo, owner and chief bottle washer of Lindemann Engineering – and the person who single-handedly saved MO’s 24 hour Grom race effort – to determine the biggest misconceptions concerning the suspenders on our favorite two-wheeled vehicles. So, let us take a look at, according to the vast knowledge base of Ed Sorbo, the Top 10 Misconceptions about Motorcycle Suspension.

10. There are sweet suspension numbers that will work for every rider

While most people are aware that there is no free lunch, you’d be surprised at how many riders believe that there are a series of magic suspension settings for their bike that will transform it into a machine capable of performing feats once thought the province of only MotoGP gods – or at the very least make them capable of riding faster than their buddies at the next track day. Well, we hate to break it to you, but suspension settings are determined by a variety of factors, not the least of which is the size and weight of the rider. For one group of settings to be the best for a particular motorcycle’s suspension independent of the rider and conditions is ludicrous, whether you got them from a well-worn copy of your favorite magazine, a forum devoted to that motorcycle, or the whispered ramblings of your neighborhood homeless person that you overheard while he was in 7-Eleven buying a replacement roll of tinfoil protective headgear.

9. Increased preload can make up for a weak spring

“Spring rate is spring rate, and adding preload is just storing energy in a spring,” notes Sorbo. Let’s define our terms: spring rate is how strong a spring is, namely how much weight it can hold up over a given distance. One common way to measure spring rate is inch-pounds or what weight is required to compress the spring one inch. So, a 100-lb spring is compressed one inch by a 100-lb weight. For every additional 100 lbs, the spring gets one inch shorter.

When you crank preload into your bike, you’re storing energy in the spring. If you preload a 100-lb spring one inch, then placing less than 100 lb on top of the spring will not compress the spring more. So, it doesn’t move anymore until you add more than 100 lb of load to it. Placing 200 lb on it will compress the spring an additional inch.

If you were to instantly remove the 200 lbs, the spring would only decompress an inch, but it would do so with the force of a spring compressed two inches. When viewed from the perspective of motorcycle suspension, the bike with too much preload in an attempt to make up for a weak spring will bounce back more over the same-sized bump because it has more energy stored in it, which can cause the bike to wobble.

8. A well-set-up race bike will be too stiff to ride on the street

When a pro rider brakes gently for a corner to scrub off some speed, the suspension works fine for him – just like it would for you when you’re braking and not using the full suspension travel. Where the difference in riders comes into play is the maximum brake application where the suspension is fully compressed. Other suspension behavior follows this same pattern. In other words, the bike will behave just fine on the warmup lap and in anger during the race.

7. Suspension fluid needs to be replaced regularly

Apparently, I’ve been guilty of wasting time, effort, money, and oil on this one. According to Sorbo, modern oils don’t lose viscosity or break down – and by modern oils, he means oils produced in the past 20 years or so. To test his theory, he took apart a Penske shock that was 14 years old and compared the oil from inside the shock to fresh replacement oil. When backlit, it looked almost the same. Next, he had it tested, and it was still good to go, according to the Silkolene factory in England. He followed up with a test at the Lucas Products factory in California. How did he know the oil hadn’t been changed in 14 years? Well, he had knowledge of the shock through its 14-year life (being the first owner), so he could be certain of the oil’s history.

For street riders, Sorbo says the oil doesn’t need to be changed unless the seals start to leak, since fresh oil will be part of the seal repair, anyway. He explains that the recommendation of frequent oil changes for street riders is simply “bullshit propagated by guys who have suspension shops who want more work.”

6. Suspension stiction is a big deal

Short answer: It’s not, and it’s certainly not worth the thousands of dollars some riders spend on special coatings.

To visualize stiction, try this: Think of a fishbowl full of water. When you go to slide it, the water sloshes. Once it’s moving, changing the rate of movement doesn’t cause it to slosh nearly as much. The same is true of suspension components. Stiction plays a role in measuring sag (which is why, historically, riders have been instructed to take the average of two or more measurements) because the movement is very slow. Similarly, stiction feels like a big deal when reassembling your fork because of the effort required to compress the components when they’re empty. While it may seem like a lot when working with your hands, compared to the forces encountered on the road, the force values are extremely low.

Sorbo says that stiction behaves in the exact opposite way of air resistance. The faster you go, the less stiction affects things. Stiction only really affects things when they are stopped and you’re trying to start them moving. On the road/track, the forces are much higher and the force required to overcome stiction is comparatively so small that Sorbo says it doesn’t matter.

5. Nomenclature does not matter

We’ve heard it all in the American culture wars: Words have meanings and affect people’s perceptions of events. Sorbo posits that we’ve been using the wrong words when describing suspension components and behavior. Springs are not soft or hard; they’re weak or strong. Damping is not soft or hard; it is fast or slow. While it may sound nitpicky, the soft/hard terminology can actually limit your thinking when trying to solve a suspension issue.

If you think suspension fast/slow, you will naturally add or remove damping to achieve the desired result. If you’re thinking the ride feels hard, you will want to make it softer. What if the ride is hard because the suspension is in the wrong part of the travel? In this case, you need to increase the compression damping (which is, unfortunately, frequently labeled hard on the adjuster and is probably the cause of the poor word choice in the first place) to slow down the dive of a front suspension, preventing it from reaching the bottom portion of the stroke where the progressive nature of suspension makes it feel hard.

Got it?

4. Fork caps need to be tight

For some reason, people like to make sure their fork caps are super tight, but it’s really unnecessary. Over torquing the caps is bad for threads and makes disassembly difficult. The simple truth is that the top triple-clamp pinch bolt will hold the caps in place. You don’t need to pump up your muscles tightening the cap. Just stick to the factory torque value recommended in your factory service manual. (You do have one, right?)

Tip: If you’re going to remove a cap, loosen the top pinch bolt and loosen the cap before you remove the fork leg from the bike.

3. It’s always the bike’s fault

Sorbo sums the issue up in three words: “Coasting is evil.”

If you want your bike to handle better in a problem corner, make sure you’re on the gas or on the brakes. The suspension gets stabilized by the load. So, you’re either pushing it down with the brakes or lifting it up with acceleration. When coasting, the suspension is not loaded and therefore unstable. Stay on the gas or the brakes, and don’t be wishy-washy and coast if you want the suspension to work at its best.

Bonus misconception: The back of a motorcycle squats under acceleration. In reality, the rear suspension extends. Don’t believe this? Watch a bike on a dyno or look at a picture of a bike doing a wheelie. The squatting sensation comes from your butt being compressed into the seat.

2. Aftermarket suspension components are always better than stock

According to Sorbo, there is no significance difference in terms of tolerances. The difference is in the compromises the manufacturer needs to make. Think of the range that encompasses a novice street rider and seasoned track rider that the OEM needs to accommodate. However, in reality, aftermarket suspension manufacturers don’t know any more about the buyer of a shock than the OEs. While an aftermarket shock is easier to disassemble for reshimming than a stocker, once they are apart, the same shim stacking technique is used to tune the shock to the requirements of the load it will need to handle. Once an OEM shock is revalved, it is essentially an aftermarket unit. While some built-to-a-price-point bikes will benefit from aftermarket suspension, Sorbo claims the majority of sportbikes, which are what he typically works with, are the primary focus of this statement.

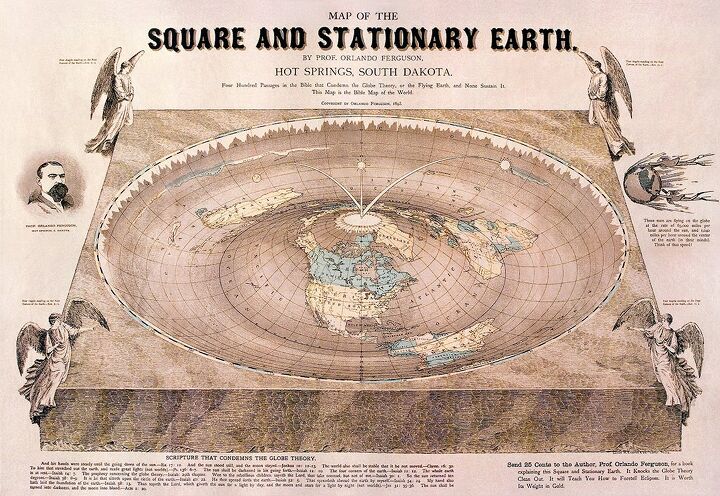

1. The earth is flat

Our power to deceive ourselves is unlimited. Think of when humans believed that the sun and planets revolved around earth. All kinds of crazy theories were created to account for the times when their movements didn’t mesh with the reality of the earth being the center of the universe.

The same is true of suspension. If you believe that the changes you made will make your bike handle better, your lap times will drop. If you trust your suspension tuner, and he tells you that he has made a change that will help in a problem part of the track, you will most likely believe that the bike rides better, and your lap times will drop. While this is good for the tuner (and many tuners have stories about how they told a rider that they’d made a requested change when they hadn’t), it’s better for you to know that the earth really does revolve around the sun.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

I'm wondering about the "bonus misconception". If I stand next to my bike and rev it, the back end squats.

So does viscosity of the fork oil really matter? How much does it affect the performance of the suspension overall and in relation to the rider/passenger/luggage weight?