2010 Oddball Sport-Touring Shootout: Ducati Multistrada Vs Honda VFR1200F Vs Kawasaki Z1000 - Motorcycle.com

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Your riding buddies say they can tour on any bike. You say most touring-oriented bikes have a sporty side and therefore make the best sport-tourer.

Oops! Did we just allude to one of the more controversial, even incendiary, topics in modern motorcycling?

Today, when someone utters the word sportbike, the likely response is a GSX-R, an R6, a Honda CBR, or some such thing. But ask a rider to describe his or her ideal of a sport-touring machine, and the answers are wide ranging.

Sure, lots of folks would naturally point to the likes of Honda’s venerable ST1300, Yamaha’s FJR1300 or BMW’s K1200GT or R1200RT, as prime examples of sport-tourers. Each bike offers good to great wind protection, hard saddlebags as standard, robust engines and some darn good handling qualities.

Yet for every rider that sees those sleds as icons of S-T, many other enthusiasts would scoff at the idea of most of them handily slicing up canyon roads.

To these folks, practically all that’s required is a tank bag, a set of soft saddlebags lashed to the tail section of their R1, and maybe a GPS or other accessories as-needed. Voila! Instant sport-touring motorbike! “After all,” they say, “Sport touring is about sport capability while traveling, and my bike equipped the way I want it is lighter, handles better, and costs less than a turnkey ST.”

Pursuing the unknowable

We like banging our heads against the wall ‘round here every now and then. So what better way to keep the tradition than to see if we can answer the question: What is a sport-touring motorcycle?

Three of the most interesting and inspired motorcycles to be released in 2010 are assembled here, and they made for a decent representation of the kinds of machines that could be considered as possible sport-touring steeds.

Although we didn’t enlist a purely sporting sportbike, we made due with the next best thing: a 2010 Kawasaki Z1000.

The nearly naked standard/streetfighter-inspired Z, bedecked with nothing more than a flyscreen, possesses the same minimalist spirit, if not more so, as a race-repli sportbike. Yet the Z still offers some comfort in the form of its upright-ish riding position that’s far less committed than the race-ready tuck many sportbikes demand.

Also, the Zed’s inline-Four is revvy and closest experientially to a sportbike engine when compared to its fellow competitors in this three-bike experiment.

The next mule subjected to the question that might not have an answer is the sultry, technology-laden, and rather pricey, Ducati Multistrada S Sport with accessory saddlebags and low seat.

The Multi offers the most upright riding position in this small collection of bikes; a manually adjustable windscreen and minimal bodywork provide decent wind protection.

As an S model our Multi comes with electronically adjusted Ohlins suspension and ABS Brembo binders; various carbon-fiber treats add to the MTS’s upscale character. Standard on all Multistradas are four rider-selectable engine maps, as well as DTC (Ducati Traction Control) that provides eight levels of TC – also rider-selectable.

The Multi is by far the most loaded boat in the bunch, at least in terms of gadgets.

Finally, we come to the motorcycle many enthusiasts might argue as the closest definition of a sport-tourer of the three machines gathered: the VFR1200F.

Wholly revised from previous iterations, Honda’s VFR is nothing like the Viffer you knew years ago. A big leap in displacement took the venerable VFR’s V4 engine from 782cc to 1237cc; everything else about the Viffer12 is a departure from the VFR800 Interceptor, including the new VFR’s optional Dual-Clutch Automatic Transmission.

Unfortunately, circumstances didn’t allow us the use of the new auto-trans Honda, but Honda’s CBS (Combined Brake System) with ABS is standard fare on all the VFR1200 models.

To make the VFR as touring-oriented as possible, our test unit was outfitted with accessory saddlebags, topbox, heated grips, centerstand and low/narrow seat, along with a few other lil’ odds ‘n’ ends. A wind-cheating add-on for the windscreen deflector and a wind deflector set for the outer portion of the upper cowl ¬were also included.

We’ve reviewed the dickens out of each bike (or so it feels) in previous evaluations, so simply refer to the single-bike reviews of the VFR1200F, Multistrada 1200 and Z1000 for more comprehensive insight to each bike. Additionally, the Multi has gone head-to-head with BMW’s GS, the VFR with the K1300S and the Z1000 tangled with Triumph’s Speed Triple.

Oh, the tales a dyno can tell!

Three different engine configurations, an inline-Four, a 90-degree V-Twin and a 76-degree V-4, seem only to further muck up, rather than simplify, the quest to pick the perfect sport-touring two-wheeler.

A displacement deficit – about 15% to the Duc and about 18.5% to the Honda – for the 1043cc Z equates to a peak power shortcoming for the streetfighter of the group. The hard numbers reveal the Kawasaki suffers from nearly 18 less peak horsepower compared to the VFR’s 141 hp, and a narrower gap to the Duc’s 132.5-peak hp.

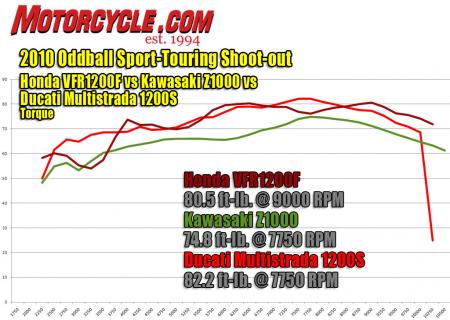

Peak torque production is less an issue for the Z, as it’s nearly 75 ft-lbs isn’t disappointingly far from the Viffer’s 80.5 and Duc’s 82 ft-lbs. More important than final numbers, however, is the Z’s fluid torque line.

The Kawi takes a little dip ‘round the 3K-rpm mark compared to a dramatic drop in that same general rpm range on the VFR. Although the Z’s midrange performance isn’t as impressive as that of the Ducati or the Honda’s, the Kawi’s power and torque development is the most linear, and it carries 110 lbs less weight than the VFR.

The Z’s smooth, linear response translates into predictable power for the rider. And predictable engine performance translates into confidence in the bike.

As user friendly as the Z’s engine is, though, we must give due credit to the Ducati for the exhilarating thrust its Twin produces as the 5K rpm mark arrives. The Italian two-wheeled stallion accelerates hard at this point, giving hint to its race-bike heritage.

“This odd bird produces effortless speed from its thumping V-Twin. I frequently saw a higher number on the speedo than I expected,” said Kevin Duke when not in the company of law enforcement officers.

You can’t help but find the rush of power intoxicating as you’re easily sucked into seeking more of that grunty Twin power. Low-rpm fueling on the MTS is snatchy (as it is on most all Ducs), but after approximately 3000 rpm throttle response is good.

Go-power from the Honda’s V-4 has its own character.

It’s distinct from the other bikes, in that it’s revy like a sportbike, yet torquey like a Twin. When the tach needle races to the top of the dial it’s easy to lose sight of your road speed, as the V-4 is deceptively smooth running, and fast!

However, while sailing the interstates and canyons we noted what felt like a serious drop in the Honda’s power in the 3000 to 4000 rpm range.

The Honda’s torque production graph, from just after mid-2000K rpm, dips for approximately 1000-rpm. It then spikes to 4K, then takes a less dramatic dip ‘til approximately 6000 rpm at which point torque finally builds confidently and in a fairly smooth pattern.

By itself, the above description of the V-4’s performance doesn’t sound unlivable. But overlay the VFR’s graph atop the Ducati and Z’s flat liner-by-comparison charts, and the Honda’s chart mimics a seismograph reading from the Caltech seismo lab.

It turns out the Honda’s e-brain – or more correctly, the brains at Honda – decides that what a rider requests of the V-4 via the twist grip isn’t really what the rider is going to get. No matter how nicely the rider plays.

Following up on a similar issue reported on in Cycle World's August issue, we conducted a second-gear dyno pull for the VFR to see how dramatically the bike’s brain limits power. Holy nosedive!

In second gear the VFR’s torque, and especially horsepower, plummet and spike dramatically, back and forth, from around 3000 rpm to the low 5K-rpm neighborhood. The Honda’s second-gear dyno chart looks like the Dow-Jones following jobless rate announcements: crash!

The reason?

By all accounts, this is a programmed reduction of power, presumably designed to save the VFR’s rider from himself. As if to say, “You want the truth? You can’t handle the tru… er, power!”

This begs the question; why not simply endow the VFR with rider-manageable fuel mapping, as is nearly commonplace on a number of today’s motorcycles?

Opinions are like blankety-blanks: everyone’s got one

“The electronics package on the Multi is very impressive, with a ride-by-wire throttle and traction control,” says Kevin. But his discerning eye also notes “with all this techno wizardry, we might expect available cruise control and self-canceling turn signals.” The same questionable omissions exist on the VFR, a bike that also uses ride-by-wire technology, and is available with a dual clutch trans – a hi-tech piece of kit unique to the VFR in the moto world.

Something the Honda and Ducati share is good wind protection, although the VFR’s accessory wind deflector seemed to create more buffeting than we’d like. As a naked bike, the Z1000 is virtually devoid of wind protection. Or so it would seem. The Z’s radiator cowling does a surprisingly good job of protecting the rider’s legs and lower body from the wind.

As our one tart-up for the Z’s tour, we enlisted Laminar Lip in an attempt to increase wind protection while minimally affecting the Z’s streetfighter visage. They cooked up the Speed Shield version seen in these photos, and it is now a new addition to LL’s catalog, costing $84. It attaches simply via burly hook-and-hook fasteners, so no drilling is required.

Perhaps the mostly unfaired Kawasaki can fake it pretty well when it comes to wind protection, but as the bike isn’t intended as any type of tourer, storage is nonexistent. Like Jeff Cobb did, you’ll have to strap some type of soft luggage or saddlebags to the Z’s saddle if you need stowage.

Conversely, this is one area where the Honda shines with its OEM-available hard saddlebags and topbox!

The color-matched topbox easily held a Shoei RF1100, with enough room to spare for gloves, a ball cap and other small, pliable items. The saddlebags didn’t accommodate any of our full-face lids, but they are otherwise deceptively roomier than what they appear.

Also, the bags are narrow enough that California riders will appreciate how easily a saddlebag-outfitted VFR is able to handily split and filter traffic. The Honda’s bags attach and detach in the blink of an eye, and the lid latch system is intuitive and pretty darn solid overall.

The Duc’s bags, on the other hand, are less robust, can seem cumbersome to operate, and as we noted in the BMW GS vs. Multistrada comparison, the Multi’s right-side bag’s volume is quite limited, as it has to account for the exhaust.

In the battle of the goodies, the Viffer’s heated grips work well, getting rather hot on the highest setting, to the point that thin gloves allow too much heat through. But we’d rather have that as an issue than warmers that don’t warm enough. The warmers are operated via an inconspicuous button on the left bar with a fairly simply routine to get to your desired temp setting. Elements that heat more on the fingers than on the palm is a clever design feature.

Although our Multistrada S Sport didn’t come with grip warmers, we need to note that the S Touring model includes them as standard. And the Z, well, again the Z has zero extras. Better buy the warmest gloves you can!

Each of us had our own list of peccadilloes we kept against one bike or another, but something we fully agreed on was the Z’s quicker, sportier handling. When it came time to run through the twisted pavement, the Kawi simply put the biggest grin on our collective face.

Jeff characterized the Kawasaki’s steering as “ultra-quick and effortless with the wide bar.” He’d get no argument from Kevin or I. Kevin solidified this bike’s place as the handling champ when he stated it was “ solid at any speed and easiest to manage in tight maneuvers.”

The Honda might not have the same sportbike-like initial steering response of the Z, but it’s an able handler nevertheless, and it’s reassuringly stable mid-corner and at high speed. Slow-speed handling, however, makes the Viffer’s heaviest wet weight of the bunch at 591 lbs (481 lbs for the Z, 478 lbs for the Duc) apparent.

It feels more cumbersome than the others when picking around parking lots or sneaking by a line of cagers at stoplights. The Honda’s plumpness also seems to overwhelm what we believe is its too softly sprung shock.

The VFR provides a remote dial for shock preload. To mitigate a somewhat wallowy feel from the rear, we cranked the dial to 23 out of approximately 26 available clicks. Even at that setting it might’ve improved further with a couple more clicks.

Although a remote dial is handier than wrenching on dual locking rings or a ramp-style adjuster, the Honda’s dial seemed too small to get enough leverage for those last few clicks when effort really increases as the spring gets mashed down. Adding to this difficulty is the dial’s nearly flush placement between the right-side footpeg boot-guard area and bodywork side panel. Moving the dial outward a skosh would go along way to making it more user-friendly.

Neither the Kawasaki nor Honda comes close to the Ducati’s levels of convenience for adjusting suspension. With a few pushes of a button, the Multistrada’s electronically adjusted top-notch Ohlins make preload and damping changes in a heartbeat. And they’re changes you can feel, especially when using the four available load settings to further tweak the springy bits.

None of us is particularly chubby, but what might be pegged as “aggressive” riding styles (at times, anyway) in combination with the Ducati’s long-travel suspension had us often adjusting load to the Two Riders mode as indicated by a pair of helmet icons in the instrument panel in search of the best combo of preload and damping.

For assertive canyon carving, the single rider, and rider with luggage settings allowed the occasional chassis wiggle and a little more front-end dive than Kevin and I would’ve preferred when strafing canyons. On the other hand, when we traversed a gnarly, twisted, broken-pavement road, Jeff, aboard the Ducati, zipped down that rugged path like he was qualifying for the Pikes Peak climb.

The Multi’s forgiving, long-travel suspension made mincemeat out of that decaying piece of tarmac.

Setting the Duc’s selectable load setting to its firmest (two riders w/luggage) preprogrammed setting proved a bit much; over rough pavement the front end wasn’t forgiving enough for us. And as Kevin remarked during our ride, the increased firmness slowed turn-in response somewhat. However, the Ohlins e-suspension has a range of rider-customizable settings, so most Mulitstrada riders should find a setting to suit their needs.

The Honda and Ducati are each equipped with ABS, while the Kawi isn’t.

Regardless, all three machines provide good braking performance, but we were most impressed by the stopping power and ease-of-modulation on the VFR’s combined braking set up. Kind of surprising, even to us, when we consider the Ducati’s premo radial-mount monobloc Brembos.

“Honda engineers did a great job with the VFR’s brake system,” Duke notes, “offering stellar composure, a firm lever, and ABS intervention if needed.”

Perhaps as important a quality as anything for a sport-touring sled is its ergonomic package.

For this, the Ducati takes the cake with its bolt-upright position, short, easy reach to the one-piece handlebar, adjustable levers (of which the VFR and Z have also), broad saddle that’s neither overly firm or soft, and most generous legroom despite being equipped with the optional low saddle. Our biggest negative with the Duc’s ergos is the buffeting the narrow windscreen causes.

The Z1000 has a more upright position than what the bikes aggressive stance might lead you to expect. And despite the rider’s hair-blowing-the-wind exposure on the Z, wind buffeting is just about nonexistent. But as 6-footer Jeff remarked at the end of a long day, his neck “felt achy” from fighting against windblast inherent in a naked bike’s design, and could see how a taller accessory screen might help.

As the sportiest sport-tourer here, the VFR puts the rider into the most forward posture. That’s not to imply it’s a hunched up position like a repli-racer, but the Honda’s ride position put the most weight on wrists out of the three bikes. However, unlike on the nude Z, a rider can tuck in behind the VFR’s wide windshield.

The VFR, like the Ducati, came with a low/narrow seat option, but after having ridden it, it’s not an option any of us would choose for ourselves.

“The seat is quite narrow at its forward end, so it doesn’t have enough long-range support for short riders sitting up at the tank junction,” lamented Kevin. Jeff had virtually the same complaint.

An additional drawback with the Honda’s low seat is that it shortens seat-to-peg distance. I found it bordering on cramped feeling after long stints on the VFR. However, if you’re a person that could genuinely benefit from the low/narrow seat, a cramped seat-to-peg scenario may not be an issue.

Seat height for the Z is 32.1”; the VFR’s standard saddle height of 32.1” is reduced to 31.3” with the low/narrow saddle option. As its looks might give away, the Multi has the tallest seat with a 33.5” height. The low seat option for the Ducati reduces saddle height to 32.5”.

Finally, we obtained a good feel for fuel economy from this trio along our journeys. Observed economy for the Duc was 36 mpg, the Z1000 at 34 mpg and the VFR with 32.5 mpg.

Resolution Road

In our quest to define or explain what makes for a sport-touring bike, have we come to any definitive conclusions or merely slid a slippery slope? Perhaps some final thoughts might lead to a resolution…

“The VFR is a super-slick package,” states Kevin, “offering a GT-like experience and shaft-drive maintenance freedom.” On the other hand, Jeff and I found the Honda’s driveline lash and shaft jack bothersome.

“No way does this improved shaft drive utterly negate the shaft jacking effect,” says Jeff in a matter-of-fact manner. “It is good for the long haul, and for its low maintenance, but you do feel it is not a chain.” And we were all put off by how the Honda dictates throttle response. Kevin said he felt “disconnected from the immediate feedback motorcycles usually provide.”

However, the new VFR is an otherwise refined icon of the sporty touring set.

Kevin espouses this quality in the VFR: “It might be the perfect bike for those who want something with a sportier edge than the Concours 14, FJR1300 or even Honda’s own ST1300. Compared to those bulkier machines, the VFR feels like a lithe sportbike.”

Incidentally, on its consumer website, Honda categorizes the VFR under Sport and not Sport-Touring.

I wasn’t alone in my admiration for the Multistrada, but I came out as its biggest proponent. Since I bias the touring side of sport-touring, I place a premium on comfort and creature comforts, something the Ducati has in spades.

Sure, its saddlebags are kinda weak next to the Honda’s luggage, but knowing this, were I to purchase a Multi, I’d simply look elsewhere for hardcases.

Additionally, though I pointed out above the limitations of electronically adjusted suspension, I’m still convinced it’s a better set up for the masses willing to pony up the extra coin. Factor in adjustable and useful traction control, selectable fuel mapping, switchable ABS, ergos that feel tailor made for me, and I’m OK with the Multi’s high price of admission ($19,995 base MSRP). If I had the scratch to play with, this’d be my bike out of the three.

So it’s down then to the underdog Kawasaki Z1000. With virtually none of the treats found on the other two, does it even make sense to force this square peg into the mostly round sport-touring hole?

“In this group, the sporty Z obviously lacks the abundant features and amenities of the other bikes, but I was very impressed with its relatively few compromises on our trip,” says Kevin. “It’s easily my preferred mount for commuter and sport-riding duties, and also performs quite well in touring mode, thanks to its accommodating ergos, low vibration and lower-body wind protection. The nearly $10K you’d save with the Zed will buy a nice set of soft luggage and lots of gas.”

More than any of us, Function-over-form Jeff was always in the Z’s corner.

“Apart from lack of ABS, this bike gives up nothing,” opines Jeff. “It could also be set up with extra lights, heated grips, heated clothing power plugs, and would be great. All it takes is motivation. You could pay to have a dealer install all that stuff, and still have change leftover.”

Hmm. Change leftover?

“The Z1000 is simply a whole lot of motorcycle for just $10,499,” states Kevin as a final push in favor of the Z. This matter of MSRP is undeniable in light of the Ducati’s as-tested price of $20,844 and the Honda’s $19,866 stratospheric as-tested price compared to its base MSRP of $15,999.

With nearly 10Gs in savings (maybe more if you can find a Z on sale!) you could almost make the Z1000 turn into helicopter, let alone outfit it with virtually every aftermarket item your heart desires for sport-touring duty.

Despite our efforts, we likely didn’t solve the age-old issue of defining a sport-touring motorcycle – clearly the Z is not what most folks think of as an S-T machine. More than anything what we’ve probably done is make obvious how hard it is to define sport-touring.

At this point, I’m just glad we didn’t have a KLR650 sitting around…

Related Reading

2009 Sport-Touring Comparison

2010 Sport-Touring Lite

All Sport-Touring Reviews and Comparisons on Motorcycle.com

All Things Ducati on Motorcycle.com

All Things Honda on Motorcycle.com

All Things Kawasaki on Motorcycle.com

More by Pete Brissette

Comments

Join the conversation