21st Century Technology

It’s a simple fact of life on two wheels: motorcycles want to fall over. Whether caused by a slippery road or slippery rider discretion, a pleasant ride can be rudely interrupted by sliding or rolling down the road, with perilous effects to your pocketbook and/or health.

But as technology continues to advance the progress of society, it also is advancing the state of the art of rider safety. New technologies in motorcycles are designed to keep us from crashing in the first place, while the latest in protective riding gear mitigates injuries suffered during a crash.

Hardware and Software

No technology can save you from yourself, especially if you’re an idiot who hasn’t considered the perils of crashing or the laws of physics. However, several new vehicle technologies have emerged to provide some measure of a safety net.

Adjustable power modes were the first assets that could be used to tame an engine’s power, effectively neutering to varying degrees the amount of power produced by the engine. Whether it’s lowering peak power, slowing the rate at which power is applied, or both, this too is a handy feature for riders on slick roads or those wanting to adapt to a machine’s full power potential at their own pace.

Mode selectors first appeared on high-powered sportbikes, but they’re now migrating to other categories as electronic controls, including ride-by-wire throttles, become more sophisticated.

In our Traction Control Explained story we detail how the different manufacturers deal with wheel slip. Essentially, TC minimizes crashes, primarily high-sides, by detecting when the rear wheel is spinning faster than the front and cutting power if the difference in speed passes predetermined limits.

Almost all TC systems are adjustable to different levels of intervention, from highly intrusive (“You’ll never crash me!”) to minimally invasive settings that are impossible to detect by anyone not holding a roadracing license.

You’re likely familiar with anti-lock brakes in cars, and its application on two wheels is similar. Preventing the wheels from locking during heavy braking allows the rider to continue maneuvering the motorcycle without fear of locking the wheels and causing a crash. This is handy in slippery conditions.

While most of these technologies are utilized in today’s advanced sportbikes – nearly every European, and a few Japanese, literbikes incorporate some combination of these three items – the same tech is trickling down to other categories as well. The sport-touring segment, for example, is adopting traction control on bikes like the Kawasaki Concours 14 and the BMW K1600. In the end, these electronic safety nets are put in place to help keep the rubber side down, giving a rider one less thing to worry about.

Hard Wear

Technical riding gear is going through continual evolution to provide improvements in protection. An open-face helmet, simple leather jacket and some Levi’s 501s were cutting-edge street apparel a few decades ago. However, huge advances in materials and construction have immensely improved protective qualities of riding gear, especially since the 1990s when impressive new textile materials have opened up many new options for comfort and versatility.

The latest innovation for street riders has roots in the dirtbike world. The Leatt neck brace has been protecting motocrossers from serious neck and spine injuries since its 2006 debut in America. Designed by trauma surgeon Chris Leatt, more than 500,000 have been sold around the world, and more than half of those sold just in America.

The STX Road brace took lessons learned in the dirt and adapted it during 2.5 years of testing to be worn comfortably over a street rider’s jacket or leathers. Instead of the dirt version’s single thoracic strut over the upper spine, the STX Road uses a pair of “wings” that rest on a rider’s scapula region of shoulders. The two wings ease fitment for street use with back protectors and/or speed humps.

The main structure of the STX is comprised of fiberglass-reinforced polyamide resin augmented by aluminum and carbon fiber components and EVA (closed-cell molded foam) cushioning. It weighs 750 grams (1.65-lb) and comes with a two-year warranty.

Leatt says 60% of all fatal spine injuries are injuries of the neck, so there’s a lot at stake here. The key to a neck brace, says Leatt, is “alternative load path technology” in which it absorbs the load path of the neck in a crash and directs it elsewhere.

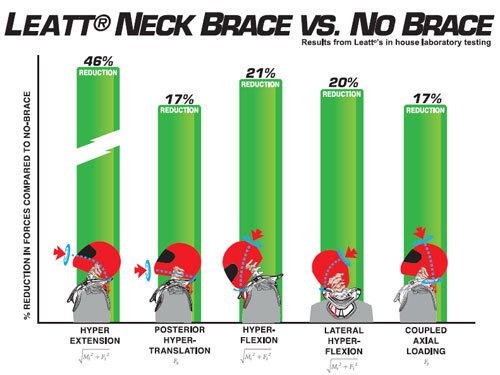

Basically, it restricts the amount of distance a helmet (and head) can be displaced during a crash. Leatt’s testing reveals the STX offers a massive 46% reduction in hyper-extension forces in which a head is rocked backward.

The STX has four adjustment areas for a customized fit: overall width in 10mm increments through sizing pins; rear struts able to be slid backward or forward tool-lessly; angle of scapular wings via a wedge insert; and its height via removable padding over the shoulders.

The STX is available in three sizes, and a Large/XL was sent for our evaluation, the middle size offered between the S/M and XXL. Because of my dragracer’s build (read: scrawny), the brace seemed a little large front to back, even in its slimmest setting, so the smaller size might’ve fit a little better.

After a little familiarity, strapping on the STX is a cinch. Simply open one of the cam buckles from either side, slip it around your neck, then reattach the cam buckle by snapping it into place. During our testing, we were surprised at how unobtrusive it was right out of the box.

There is no impediment to rotating a head sideways to check over a shoulder, which was my greatest concern. The STX is designed to work best on motorcycles with an upright riding position, but it even accommodates sportbike ergos as long as you don’t get into a full race tuck position.

The STX is a great development in safety gear, but a rider needs to be dedicated to his/her safety to want to pull it out and wear another piece of gear, and it does need to be stowed somewhere after a ride. Adding more stuff to anything is less convenient, but that’s ($395 MSRP) the current price of extra safety. More info can be found at http://www.leatt-brace.com/.

Bag Man

When it comes to wearable protective technology, airbags are the trending topic. A now rudimentary safety feature for automobile passengers, the cushioning qualities of quickly inflatable airbags are now available in various apparel products to increase rider safety.

Apparel airbag technology is in its infancy, so the available products are rare and expensive. Motorcycle racing, specifically MotoGP, where crashing is expected and rider safety is paramount, has been the proving ground of this technology, and apparel manufacturers are now producing their efforts for public consumption.

Two of the most recognizable motorcycle leathers manufacturers now have one-piece airbag-equipped racing suits available in America. Dainese’s D-air ($3,999) and Alpinestars’ Tech Air ($4,999) are at the forefront of this technology. Click on the above links to learn full details about each system.

Less expensive options in the form of vests, such as Spidi’s DPS airbag system, do exist. And, at $599.95, Spidi’s Neck DPS Air-Bag Vest (designed to fit over your current motorcycle jacket) is a much more affordable option.

However, the difference between Spidi products and those from Alpinestars and Dainese is the technology incorporated into the garment. Where Spidi utilizes a tether attached to the motorcycle to determine when a rider has been ejected then deploy the airbag, Dainese and Alpinestars utilize accelerometers, gyros and sensors to determine when a crash is taking place.

A great disadvantage of the D-air leather suit is that following a crash the suit (if undamaged) must be returned to the manufacturer in Italy to be reset for future use. The Alpinestars suit also needs to be sent back for new nitrogen canisters, but the Tech Air suit has two charges so it can protect the rider in the event of a second crash. The Spidi apparel has only a single charge, but users can purchase and install replacement CO2 cartdiges themselves.

There are other apparel manufactures producing airbag products, and as the technology becomes more available, we expect to see ever increasing uses, more options and soon a ubiquity of airbag technology in motorcycle apparel.

Related Reading

Traction Control Explained

Dainese D-Air Racing Leathers Make U.S. Debut

2010 Alpinestars Electronic Airbag Technology

Alpinestars Tech Air Race Suit Wins PopSci Best of What’s New Honor

More by Kevin Duke/Staff

Comments

Join the conversation