Testing Harley-Davidson Screamin' Eagle Upgrade Kits For Milwaukee-Eight Engines

Factory power has its advantages

Every Harley-Davidson owner and just about every motorcyclist knows that the Motor Company’s line of performance products is called Screamin’ Eagle. However, many may just look at the upgrades as being mostly the same as the multitudes of aftermarket hop-up parts available. Since the release of the Milwaukee-Eight engine in the 2017 Harley-Davidson touring models, the engineers and media people behind Screamin’ Eagle thought that now would be a good time to explain – in detail – what they feel sets these components apart from the others on the market. So, we were sent out to Milwaukee to learn about and experience first-hand how the Screamin’ Eagle kits can improve the ME’s performance without many of the compromises required by aftermarket kits.

2017 Harley-Davidson Milwaukee-Eight Engines Tech Brief

In my 20 years writing about motorcycles, I’ve been fortunate to ride many bikes with any number of performance modifications. From drag bikes to Formula Xtreme competitors to high-powered street customs (including a dual supercharged Valkyrie), I’ve sampled the best of what accomplished builders and mechanics could create. I’ve also gotten to throw a leg over bikes that would barely idle, offering mind-bending WFO acceleration but refusing to maintain neutral throttle, making them pretty useless as street bikes.

Additionally, all of these built engines, whether they were examples of either good or bad tuning, shared one feature: their alterations voided factory warranties. Now, this is no big deal to gearheads. They live for the knowledge they gain about motorcycles by fiddling with their projects. For the average enthusiast, losing the warranty could be a big deal.

All Screamin’ Eagle performance parts allow for the owner to maintain the factory warranty on the powertrain. Also, the kits were developed alongside of the engines. In the case of the Milwaukee-Eight, the kits are already available as the engines themselves are being released. The aftermarket will have to play catch-up. Additionally, if purchased at the same time as the motorcycle, the Screamin’ Eagle kits can be included in the bike’s loan. Finally, since the kits were developed by the same manufacturer as the engine, one would assume the kit would avoid the teething pains often associated with the final tuning of hop-ups with aftermarket parts.

All the world’s a stage

The cliché about performance modifications goes something like this: Speed costs money; how fast do you want to go? Since the Milwaukee-Eight is the newest engine released by Harley, I’ll primarily focus on the upgrades for it. As with everything, the Screamin’ Eagle buyer can buy into different levels of modifications – with each level adding to the components (and price) of the previous one.

Stage I is the least expensive and incorporates the two aftermarket parts that most motorcyclists put on their bikes: intake and exhaust. Using the 2017 Road Glide as an example, the Street Cannon Performance Slip-On Mufflers will retail for $499.95, and the Heavy Breather Performance Air Cleaner takes care of the intake for $399.95. Additionally, the Stage I upgrade includes one of the most commonly overlooked components in helping an engine breathe better. The EFI adjustments made possible by the Screamin’ Eagle Pro Street Tuner ($299.95) will get the best performance out of the new intake and exhaust by using maps developed by Harley engineers.

According to Screamin’ Eagle press materials, the end user can expect approximately a 10% performance increase throughout the rpm range. (Pro tip: Riders who forego the Pro Street Tuner are really more interested in the look and the sound of the intake and exhaust than they are in getting better performance out of their bike’s engine.)

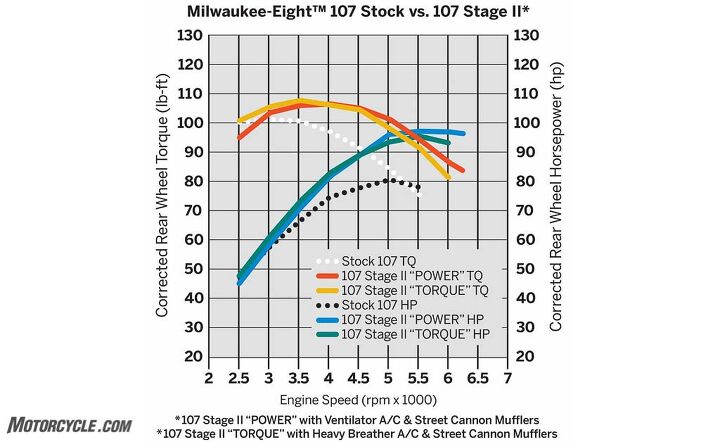

Stage II further enhances the Milwaukee-Eight’s ability to breathe by adding a choice of cams to the mix. The options include the Stage II Torque Kit which is claimed to increase torque and horsepower in the low- to mid-range rpm, beginning with a 5% bump off the line that builds to a 14% increase at 4,500 rpm. In the dyno chart shown below, the Torque Kit starts slightly above the stock cam at 2,500 rpm, builds to its peak, and then maintains a slightly lessening advantage the rest of the way to the rev limit. For your typical rider, this sounds like an ideal setup for around-town grunt or roll-on power at highway speeds.

For the folks who enjoy the stoplight grand prix, the Stage II Power Kit begins the increased power delivery at 3,000 rpm, ramping up to a claimed 24% at redline. The torque curve of the Power Kit starts below the stock curve, crossing it at 3,000 rpm before topping the Torque Kit at 4,000 rpm and maintaining a slight, but increasing, advantage all the way to redline. The horsepower curves of both kits move above the OE cam’s at 3,000 rpm. Then, the two kits are essentially the same until 4,500 rpm, where the Power Kit moves on to its higher peak and flatter fall-off to redline. These two kits retail for $389.95 on top of the cost of the Stage I Kit.

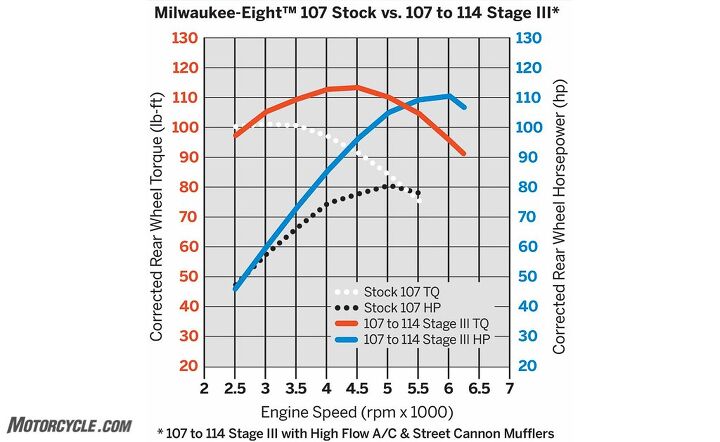

Stage III builds on the Stage I and Stage II kits by bumping the Milwaukee-Eight’s displacement from 107 c.i. to 114 c.i. In order to facilitate that increase, the kit includes: cylinders, high-compression aluminum-coated pistons, piston rings, a cam (different from either Stage II cam), valve springs, tappets, and all necessary gaskets. Once installed, the kit’s engineers say that it will produce an impressive 39% more power than stock. Unlike with the either the Torque or Power Kits, the benefit is felt throughout the rpm range with no compromises in power delivery. As with the two previous stage kits, the Pro Street Tuner will need to be programed with factory-developed engine control module settings for optimal power delivery. The Stage III upgrades, with their $1,595.95 price, are as far as the Milwaukee-Eight can be taken – for now. The Screamin’ Eagle engineers said that they haven’t reached the flow limits of the new four-valve heads, which negates the need for a Stage IV kit.

Stage IV caps off the three previous kits (for the two-valve per head engines of the Twin Cam and Sportster) with a CNC-ported cylinder head, a set of high-compression pistons and cams designed for the increased flow, plus a larger throttle body. According to Harley, the Stage IV kit delivers “up to a 40% increase in the higher rpm range.” Additionally, a stiffer clutch spring and high flow injectors are included.

When discussing this article with E-i-C Duke, he asked me why, if the changes were so easy to make, didn’t H-D just make the original equipment deliver this kind of power. My thoughts on this are two-fold. First, the MSRP would likely go up with these components being standard, and the increase might deter some potential buyers from signing on the dotted line. Second, motorcyclists like to make changes to their bikes. If the Road Glide example we’ve been following through the stages came with Stage III power in stock trim, owners would want to make them more powerful, anyway. That’s the nature of the beast. Also, different riders want different things from their bike’s power delivery. Just look at the Stage II options.

On the strip and in the streets

While I didn’t get to dyno the various Screamin’ Eagle kits that Harley had assembled for the media to ride in Milwaukee, I did get a chance to ride a stock version of each of the modified bikes I tested. Although rain shortened our riding time considerably, I was able to sample all of the modified bikes on the street and both the modified and stock versions at the drag strip. I’ll break down my impressions by kit.

For me, Stage I is characterized more by what it doesn’t do than what it does. Bear with me, this is a good thing. Instead of the flat spots frequently encountered in bikes that have had an intake kit and pipe installed by the owner, the integrity of the Milwaukee-Eight’s throttle response was unchanged – meaning the EFI tuning felt just as good as stock. While the increase in performance was minimal, depth was added to the exhaust note without becoming obnoxious, and the intake sounds (a personal favorite) became more pronounced. The slip-ons produced a sound that I would be comfortable riding with every day on the crowded L.A. streets without worrying about bothering people with the noise.

I sampled the Stage II kits on two different bikes. The Road Glide equipped with the torque kit was my personal favorite of the bunch. The EFI was spot on, as with the stock one I sampled, and the increase in torque was noticeable as soon as the bike left the line – be it on the strip or the street. Around town, the engine responded exactly the same as stock but stronger. From loafing along in traffic to passing on the highway, the additional grunt was noticeable the instant the throttle was cranked open. Also, the Torque Kit doesn’t pay much of a top-end penalty compared to the Power Kit. The Power Kit’s top-end pull made running through the gears hugely fun. In some conditions, the hit of power at 3,000 rpm was more pronounced than others, though. Perhaps, I was just hyper-sensitive to any abrupt delivery in the rainy-slick conditions on the street, but I could feel it.

On the drag strip, the difference in my times between the Torque Kit-equipped Road Glide and the Power Kit-equipped Street Glide was minimal – a mere 0.073 second (12.977 sec. vs 12.904, respectively). However, I need to note that the clutch on the Stage II Power Kit equipped Street Glide was slightly grabby, resulting in a couple tire-spinning, somewhat sideways launches. Since I wasn’t able to feather the clutch as easily as on the Road Glide (and the stock Street Glide) my launches and, consequently, my ET suffered on the Power Kitted Street Glide. My best time on the stock Road Glide was 13.046 seconds.

The Stage III-equipped Road King was a 114 c.i. beast on which I logged my quickest quarter-mile time of 12.825 seconds. Now, that shouldn’t be a surprise since, in addition to putting out the most horsepower, it was the lightest of the bikes I ran on the strip. I’m also certain that I could’ve run a quicker ET if I’d had a proper tachometer, rather than the low sampling-rate one in the LCD screen. When I looked at the tachometer, it read 5850 rpm when the engine was hitting the 6,250 rpm redline. Consequently, I made my subsequent passes by ear – almost certainly leaving some rpm on the table through short-shifts. (In retrospect, I should’ve taken a pass and noted at what speed I hit the limiter in the first three gears and used the speedometer to time my shifts, but like my clever comebacks in arguments, I thought of this after the runs were finished.) On the street, because of the silky EFI tuning, the Stage III Road King was a pussycat when I wanted it to be, but it gobbled up the pavement when I pulled its tail. Power junkies will want a Stage III Milwaukee-Eight in their Harleys.

You’ve probably noticed a theme in my comments about all three stage kits I tested, but I’m still going to say it outright: All three kits offered the refined throttle response similar to that of the stock engine. When it came to the increase in performance, that was directly tied to the level kit – and degree of expense this accounts for – installed in the Milwaukee-Eight engine. In my imaginary Road Glide project, the total costs of the components for each stage before labor is considered would be, roughly: Stage I, $1,200; Stage II, $1,590; and Stage III, $3,186. Of course, labor will add considerable cost to Stages II and III.

Given the fact that the Screamin’ Eagle performance kits were developed alongside the new Milwaukee-Eight engines, offer a virtually turn-key hop-up experience, maintain the EPA certification of the bike in all 50 states, and retain the engine’s factory warranty, these kits offer an extremely attractive package of features for your average motorcyclist who wants to pump up their new Harley powerplants. While there will always be riders who want the biggest and most powerful engines available – and builders capable of creating them – I’m pretty sure that there are a ton of riders who would love to have their upgraded engine sorted out before they even roll their new bike out of the showroom door.

In a world where people are less willing to wait for things, this might be a powerful motivator. Regardless, my two days of riding the Milwaukee-Eight’s three stages of Screamin’ Eagle upgrades illustrates that Harley-Davidson has put as much effort into the riding experience of its hop-up kits as it did with the stock engine. After all, it;s the experience from the saddle that really counts.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

Thanks for the article Evans. I couldn't agree more with the comments posted about Harley making it too difficult and expensive to modify a bike to ones particular desires. Even if financially able, I'm not willing to be screwed around with, neither my time or my time. When I can custom order the bike I want I'll spend plenty of money on it. Until then HD can keep their damn Iron Horses out to pasture. MADE in America doesn't mean I'll be HAD in America.

Bad testing methodology. The ET is very 60ft dependent and the horsepower increases are better quantified by the differences in the trap speeds. Please revise the article.