All About Chains

Few pay much attention to the racing technicians running around the starting grid, squirting the last shots of chain lube seconds before the flag drops. But for tech-freaks like me they are fascinating people. That's why I couldn't believe my luck when I met a true behind the scenes racing man with years of experience servicing World Champions from GP racers to MXers, a man so influential in the development of motorcycle chains that he is only referred to formally. This is a man with no first name.

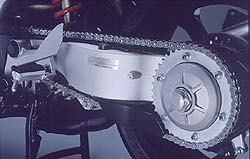

For twenty years Mr. Longoni has been the chief race technician for the Italian drive-chain makers, Regina. And that means having taken care of the chain needs of many World Champions. Motorcycles have changed a lot since he became involved with racing, at the last days of MV Augusta's four-stroke GP dynasty. Even though the chains still look very much the same, the improvements in the tec

"You have to look closer and deeper" says Longoni. "The GP bikes of the late seventies like the ones Roberts rode made just over 110-120 HP and used a 530-size chain weighting about 2.5 lb. per yard. Today GP racers produce close to 200 HP but manage with a 520-size chain that weights only 2.3 lb. per yard. That's no mean feat. All those internal improvements in materials and technology are simply not visible to the naked eye."

But sheer horsepower is not everything. Longoni knows his rider's chain demands. For example, Randy Mamola's wild riding style totaled chains at a rate three times faster than other riders on similar machines.

Unreasonable demands on chains are to be found not only in hyper-power road racers. MXers with 12" suspension travel and 60 HP engines are quite a challenge, too. Chain tensioning, so critical for proper power transfer, varies a lot and the mud and sand don't help either. Mr. Longoni has spent quite a lot of time dealing with MXers needs as well as those of speedway bikes and even ice racers.

All those race teams are sure looking for a better way to transfer power. But is there an option to the classic roller chain?

"The toothed rubber belt seemed at first like a nice alternative and has even been raced, but it is not the answer," said Longoni.

A toothed belt's power limit is directly related to its width. That might be OK for a stock 60HP (or 90HP) Hog but above that a drive belt will have to be very big to the point of widening the whole bike to make it fit. Also, unlike chains, individual belts are not adjustable.

So, for the foreseeable future we're stuck with our old chains. The last big step in chain development was in the eighties with the mass introduction of the O-ring sealed chain. Those little rubber rings have solved what was the chain maker's biggest headache for many years: Loss of lubricant. The load bearing pins and bushings that enable a chain to bend over a sprocket have precious little oil to keep them happy. As if that wasn't enough, high centrifugal forces that occur when the chain turns around the drive sprocket throws away the oil. "The only reason for chain wear is the loss of lubricant" says Longoni. The advent of the O-ring chain enabled the chain to keep its oil inside and stay lubricated were it counts for long periods.

Mr. Longoni also has plenty of tips for proper chain care. Even the cheapest chain without O-rings will last a surprising amount of time with proper care, meticulous adjustment and oiling at 350-mile intervals. To my surprise, Mr. Longoni claims that heavy gear oil applied with a brush is what many racing teams use, but this is a messy proposition and best only when the chain can be left to drip away the excess overnight. Most people spray on chain lube, which is good as long as you wait the required 20 minutes to let the solvents in the spray evaporate and leave the thicker lubricant on the chain, rather than on of the tire's sidewall.

Chain grease is not so efficient. It cannot get into the tight clearances between moving parts and the most good it can ever do is keep the chain's side plates from rusting in the winter.

Chain oil's main enemy is high running temperatures. The running temperature of a chain ideally should not exceed 160 degrees Fahrenheit (70 degrees Celsius). Above that, chain lubricant starts to thin, and the chances of it seeping out past the O-rings increase; eventually the film strength drops.

A new, too-tight chain can, in no time at all, turn into history. The best way to check chain tension, the one used by many race teams, is too ask two of your biggest friends to sit on the bike and compress the rear suspension to the point where the wheel spindle, swing-arm bearing bolt and the front chain-sprocket centerline are all in line. That is the point of maximum chain tension. Or you can compress the bike's rear end with a ratcheting tie down. Free up and down movement at the middle of the chain's bottom run should be about half an inch (13 mm) with the suspension compressed.

Of course, a loose, dragging-on-the-floor chain is not too good either. A loose chain will rub on many static parts of the bike such as the swing arm rubber buffer and frame spacers. Besides, with the chain's ability to saw through anything in its path, the added friction will again raise temperatures. Also the sprockets will suffer. A loose chain will "ride up" into the higher and weaker areas of the sprocket teeth and slowly bend them into a wicked hooked shape. Proper tensioning as explained above is the remedy.

Also, proper tensioning means a straight and true running rear wheel. A cockeyed, sideways rear wheel will place uneven stress on the chain, making one side of it work harder than the other. That is bad. A quick check can be made by sighting the chain's top run, back to front. A badly misaligned rear wheel will show as a notable kink in the chain's run line. For more exact results you can pick two eight foot (2.5 meters) straight-edged wood boards and place each on on either side of the bike, about 4" (100mm) above the ground. On a properly aligned wheel, the edges should touch the rear tire sidewall and leave equal gaps on both sides of the front tire. Adjust your chain tensioner accordingly.

Even after all this straightening it is worth checking that the chain runs even, centered on the rear sprocket. A missing 1mm washer somewhere may cause one side of the sprocket to make contact with the chain. If after some mileage one side of the rear sprocket gets shiny near the teeth it means that the front and rear sprockets are not properly aligned. A few shims or washers here and there can cure this.

Off-road riders have a few problems all of their own. The mud or sand that gets trapped between the chain and sprocket works as a fine grinding paste, totaling chains in no time. In Mr. Longoni's experience the relieved teeth sprockets available in the aftermarket help a great deal in reducing chain wear and stretch by letting the dirt out of the high-pressure area. Proper maintenance of a dirt bike's chain also means a good hosing after the ride, first drying (watch your fingers!) and only then, oiling. By the time of the next ride all excess oil will have dripped away, reducing dust pick up to minimum.

The 500 pieces or more that make up a chain lead a very unglamorous life. On the other hand, failure of just one of them means a side-lined bike. Proper care is not too hard on body, soul or pocketbook and is definitely worth it. If your chain was misaligned and distressed you will certainly feel the difference in ride quality after a well-deserved chain care session.

More by Yossef Schvetz, Mid-East Desk

Comments

Join the conversation