Inside Yamaha's MotoGP Race Shop

Rossi's and Lorenzo's bikes built here

In terms of gearhead appeal, the passion of Italy’s high-performance enterprises and plethora of world-class racetracks are impossible to beat. So, when Yamaha was deciding to set up its European headquarters for its racing operations, it chose Gerno di Lesmo, a stone’s throw from the historic Monza circuit not far from Milan.

Officially called Yamaha Motor Racing Srl, the facility is the HQ of the Movistar Yamaha MotoGP team, and Motorcycle.com was invited to tour the shop in conjunction with the EICMA motorcycle show. Leading us on the tour was Lin Jarvis, YMR’s Managing Director and Team Principal of the Movistar Yamaha MotoGP team, who was flying out to the GP season finale at Valencia the next day. It was a surprising ego boost when Jarvis said he recognized me from the EICMA videos we posted the previous day.

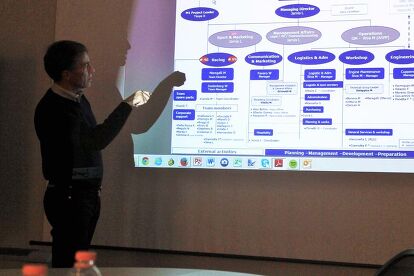

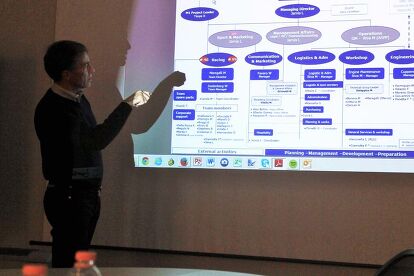

YMR was founded in 1999, with the factory taking control of the race team after Wayne Rainey’s retirement from managing the GP effort. Originally located in the Netherlands, the team transitioned to Italy in 2005. Much of the technical work takes place by 65 engineers working at Yamaha’s Technology Development Division in Japan, but several members of the Japanese engineering staff work out of Italy’s YMR.

YMR consists of 17 full-time staffers, working mostly on engine development, and there are 25 members of the team who travel to races. YMR uses eight trucks to support racing logistics: two team trucks, one engine truck and one data truck, plus four hospitality rigs.

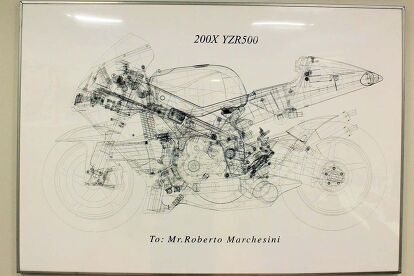

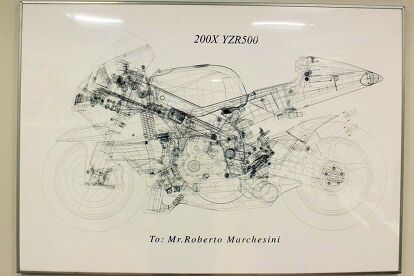

Fun fact: The designer of Yamaha’s last 500cc GP bike and of the original M1, Takano-san, became the lead engineer behind the Tricity, Yamaha’s first tilting three-wheel scooter.

One of YMR’s biggest challenges was the transition from 500cc two-strokes to the 990cc four-strokes beginning in 2002 with the first YZR-M1. The M1’s directive when it debuted was “One Mission,” referring to winning in the four-stroke era, but in the hands of Max Biaggi and Carlos Checa, the Yamaha came up short to Honda’s RC211V and Valentino Rossi’s superb riding talent. Rossi scored another championship for Honda in 2003.

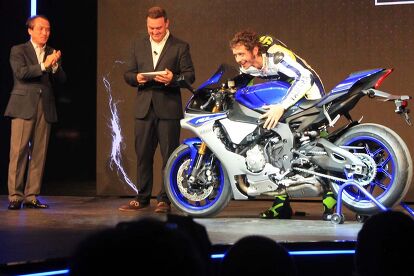

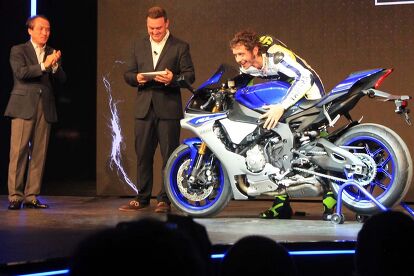

Then, in December 2003, a big move: Yamaha lured Rossi away from Honda. “It was a leap into the dark,” Jarvis recalls, referring to the “do or die” situation of having the best rider in the world on their bike. “If we failed, it would’ve been a disaster.”

As it turned out, Rossi signing with the team led to a string of championships, with VR46 winning titles in 2004 and 2005, then again in 2008 and ‘09. Spanish phenom Jorge Lorenzo also brought Yamaha championships in 2010 and 2012.

It should be no surprise Yamaha places such a large emphasis on motorcycle racing, as, unlike most other Japanese OEMs, the vast majority of its business (65.8%) comes from motorcycles. Marine products comprise 17.3%, followed by 9% in power products. Industrial machines and robots comprise 2.3% of Yamaha’s total income, amounting to nearly 10 billion euro in 2013. It employs 63,627 staffers, 55 of which attend GPs.

Yamaha currently offers three levels of support in MotoGP, led by the factory squad of Rossi and Lorenzo whose bikes receive the latest in developments. Next up is the Tech 3 satellite team that receives hand-me-down technology from the factory team. Jarvis says the performance difference between the two is “really marginal.”

Then there’s the Open-class bikes that Forward Racing campaigns with Yamaha equipment, leasing engines, frames and swingarms from the factory. If you’d like to start your own Open-class GP team, leasing a bike from Yamaha will cost a cool 800,000 euro. Honda was selling, rather than leasing, its Open bikes for 1M euro, but their lack of pneumatic valves severely hindered their performance potential.

Jarvis says a “critical difference” between the Open bikes is the less-advanced electronic software solutions for engine management and traction control. Open bikes are also allowed 4 extra liters of fuel versus the 20-liter limit on the factory bikes. In addition, the Open bikes are also allowed 12 engines during the season, while the factory machines are limited to five motors, and they are also allotted softer/grippier rear tires.

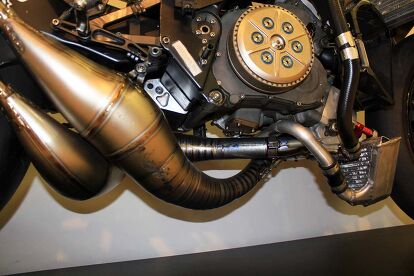

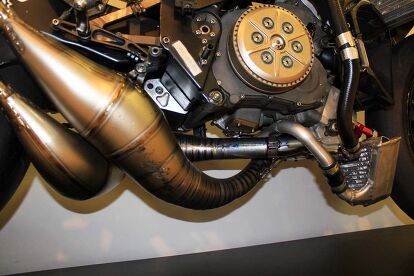

We were brought into YMR”s engine room for a brief tour, but no cameras were allowed, such is the secrecy of MotoGP technological development. We learned the latest engines use an 81mm bore, the largest allowed under the regulations, and rev to 18,000 rpm “at least,” according to YMR General Manager Marco Riva. Meticulous engine assembly requires 3.5 days, after which it is broken in on a dyno for one hour.

As for power output, I guessed 250 hp, to which Riva slyly revealed, “more or less.” Due to concerns over fuel economy, throttle manageability and reliability, chasing bigger power numbers isn’t the team’s goal, which implies potential horsepower could fairly easily exceed 250 hp or more.

Fun fact: Compared to the 2004 M1, the latest engine is said to produce 20% more power while burning 18% less fuel.

Honda, of course, is Yamaha’s arch-rival in Grand Prix racing, with each trying to leapfrog the other in technology and speed. Honda got the jump on Yamaha by their introduction two seasons ago of a seamless-shift transmission, with Jarvis claiming his rivals were working on it two years before Yamaha.

Honda also seemed to have a braking advantage over the Yamaha, with Jarvis admitting that Honda’s electronic engine-braking strategies might be better. But with 2014 regulations allowing the use of larger front brake rotors, and with Lorenzo changing his riding style to improve braking performance, Yamaha has closed the gap. Jarvis notes that, in 2004, Rossi’s engine-braking strategies involved only manual manipulation of the clutch and rear brake.

Fun fact: Yamaha’s data-logging equipment can monitor 270 parameters!

The 2014 season began as a disappointment for Yamaha, with Rossi and Lorenzo being unable to keep pace with the brilliance of Marc Marquez and his seemingly flawless Honda RC2113V. Lorenzo was recuperating from injuries, and his high corner-speed style wasn’t gelling with Bridgestone’s front tire.

But with the strong end-of-season form from both Rossi and Lorenzo, Yamaha believes it has caught up with the quick Honda. “I think we are more or less equal,” says Jarvis.

YMR is staying on the gas heading into the 2015 season while preparing for major rules changes in 2016: Michelin will supplant Bridgestone as MotoGP’s tire supplier, and the factory teams will be forced to share a common electronics package. Both Yamaha and Honda were initially reluctant to share proprietary software, especially Honda, but Jarvis believes this is a good move for MotoGP.

“Leveling the playing field is important to the series,” Jarvis acknowledges. “Hopefully it will bring down the costs for everyone.” And, critically, Jarvis says there’ll still be areas to exploit the electronics with modifications and tweaks to the common software.

If this article hasn’t yet sated your thirst for Yamaha’s MotoGP information, scroll down to see more pictures of cool stuff found at YMR. More info can be found at YamahaMotoGP.com.

More by Kevin Duke

Comments

Join the conversation

I normally don't care for backstage passes or meet-and-great type stuff. But this sure seems like it was fun tour.

I sure would like to hear that four cylinder 2 stroke again.